Teaching Young Refugees: UNICEF Educational Officer and Former Olympic Swimmer Imoto Naoko

Tokyo 2020 Sports Education- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

An Unlikely Place for a Soccer Pitch

In mid-February, when the coronavirus pandemic had yet to hit Europe, I traveled to Greece to meet Imoto Naoko, a former Japanese Olympic swimmer who is now an aid worker in the country. I accompanied her on a visit to a large refugee camp housing asylum seekers from countries like Afghanistan and Syria that is located in the neighborhood of Elaionas on the outskirts of Athens.

Entering the camp, I was surprised to see that the temporary buildings that house the refugees are arranged around a soccer pitch that is more than big enough to play futsal on. Admiring the patch of green, I watch a group of teenage girls run around excitedly on the natural turf.

Colorful temporary housing surrounds a soccer pitch inside the Elaionas refugee camp. (Photo by the author)

When I express my surprise at finding a proper soccer pitch in the middle of a refugee camp, Imoto quietly smiles and then leads me to a prefabricated classroom block, explaining that the remedial classes are about to start.

Inside the classroom, a group of around eight children wearing headphones sit at tables, their eyes fixated on tablets in front of them. Imoto goes to help a student who is having trouble, speaking to the child in fluent Greek.

Imoto heads up the education team at UNICEF’s Athens office, where she oversees a small staff of Greek employees and coordinates with a slew of non-governmental organizations. She tells me there are currently over 100,000 refugees living in camps around the country, including some 40,000 children. “Around 40% are school age and attend public schools,” she explains. “UNICEF supports the Greek Ministry of Education’s learning assistance programs and uses European Union funding to provide informal educational services.” This includes an ongoing project to develop tablet-based resources for providing students fun and engaging ways to learn Greek.

In another classroom, a teacher helps a group of young refugees who attend a public secondary school with their homework. “Like many other EU countries, Greece recently voted in a center-right government, which is making it harder for us to accept refugees” Imoto says. “I spend a lot of time thinking of ways to get the Ministry of Education to help us.”

Although Imoto has a grueling job, there is a sense when talking to her that she finds the challenge extremely fulfilling. I was curious to know what had made her go from being an Olympic swimmer to helping refugees.

A Keen Sense for Inequality

Imoto was born in Aichi Prefecture but grew up in Tokyo. She started swimming at the age of three; by 12 she had broken the Japanese junior record in the 50-meter freestyle. After elementary school, she joined the famous Itoman swimming school in Osaka with hopes of making it to the Olympics, a decision that meant living away from her family.

Her junior and senior high school years were dominated by long hours in the pool. Surrounded by powerful rivals, Imoto at 16 missed out on representing Japan at the 1992 Barcelona games by a mere one-tenth of a second. Although surrounded by the grueling demands of competitive swimming, she stood out from her peers in her plans to work in an international field one day.

Interested in what was happening in the world, every day after morning practice she would take the newspaper from her coach’s office and read through it, a habit she says she picked up from her parents. “I especially liked the international pages,” she recalls. “Reading about events around the globe made me want to work overseas, and once I got to junior high I worked really hard on my English.”

In the autumn of her final year of high school, with her sights set on the Atlanta Olympics, Imoto competed at the Asian Games in Hiroshima. Like other Japanese swimmers, she followed a strict pre-competition diet. But in the athletes’ village, she was shocked to see athletes from developing countries gleefully devouring cup after cup of complimentary sweets like ice cream and custard pudding that were available, each person seemingly vying to make the tallest stack of empty containers. Although envious of the scene, Imoto understood that unlike in Japan, the individuals would likely not find such delights waiting for them once they returned home.

After she started competing in tournaments overseas at the age of 14, Imoto says she would often notice swimmers from other countries wearing threadbare uniforms, or even T-shirts in lieu of official team attire. “Sometimes I would ask about a swimmer who posted a very slow time and learn that the person was from a place that had almost no swimming pools where they could train,” she says. “I was struck by the difference in environments and by the unfairness of the world.”

Later, around the time she started thinking about university, Imoto was reading a newspaper article about the war raging in Yugoslavia when she noticed a short report tucked in beside it describing how 1 million people had been massacred in Rwanda in the space of just 100 days. She could hardly suppress her shock. “I remember my disbelief at how half a century after World War II, Japan was at peace, but that in other parts of the world conflicts were still claiming the lives of innocent people,” she says. “And it wasn’t by faceless bombing, either. Here were people being slaughtered by their neighbors, and I was nonchalantly reading about it in the paper.”

Life After Sport

The experience helped Imoto choose the path she wanted to take after her swimming career was over, that of a humanitarian aid worker. Enrolling in Keiō University, she began studying for a degree in policy management.

In 1996, while in her second year of university, she traveled with the Japanese Olympic squad to the games in Atlanta and helped propel the 4 x 200 m freestyle relay team to a fourth place finish. After the Olympics, Imoto spent time studying international relations at Southern Methodist University in Texas while continuing to swim. After returning to Japan, she resumed her studies at Keiō while also vying to qualify for the 2000 Sydney Olympics. When she failed in her bid to make the Japanese team, she decided to retire from swimming.

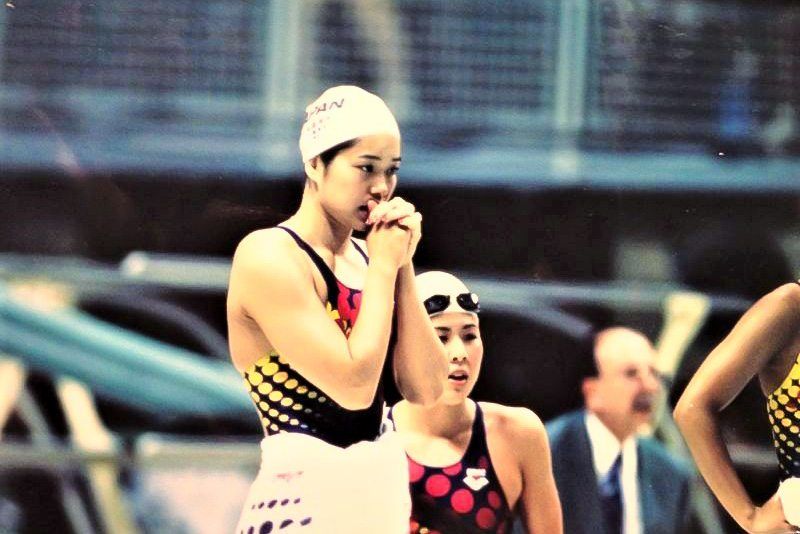

Imoto during the 4 x 200 m freestyle relay competition at the Atlanta Olympics. (Photo courtesy of Imoto Naoko)

Starting a new chapter of her life, Imoto graduated from Keiō and worked for a time as a secretary for a member of Japan’s Diet. She then took a job as a sportswriter before returning to school, earning her master’s degree in peace and conflict studies from the University of Manchester. In 2003 she traveled to Ghana as an intern with the Japan International Cooperation Agency. Imoto also took part in JICA’S post-conflict reconstruction efforts in Sierra Leone and Rwanda as a project formulation advisor.

In 2007, she realized her long-held dream of working at the UN when she joined UNICEF. With the agency, she has taken part in recovery efforts in countries like Sri Lanka, Haiti, and the Philippines. In Mali, she was involved in the launch of a project to educate citizens on Ebola prevention measures.

Imoto with young villagers in Mali. With UNICEF, she helped create a textbook to educate locals about Ebola prevention. (Photo courtesy of Imoto Naoko)

Wearing Two Hats

In 2016, the EU responded to a sudden influx in refugees from Africa and the Middle East by building refugee camps in Italy and Greece. While Italy is chiefly focused on accepting African refugees and giving them vocational skills, Greece has taken in large numbers of refugees from the Middle East and has focused on supporting primary and mid-level education. Seeing an opportunity to use her skills, Imoto applied for the post of education officer at UNICEF’s Athens office. She said she wanted to set herself a new challenge of helping child refugees while negotiating with governmental organizations in an industrialized European country. “The best way to give a refugee a better future is to give them an education,” she says.

Imoto says that when designing the refugee camp, she asked that in addition to classrooms, a soccer pitch be included. When I asked her if she wanted to use her own experience as an Olympian to teach children about peace through the medium of sport, Imoto smiled awkwardly and shook her head. “Reporters always try and frame it like that,” she says. “For me, when I plan a new classroom, it’s only natural to add a space for having fun and playing. Some people say sport is part of education, but I see it as equal. Not everyone likes going to school, but it’s necessary for surviving in society. You won’t find many children that dislike sports or play, however.”

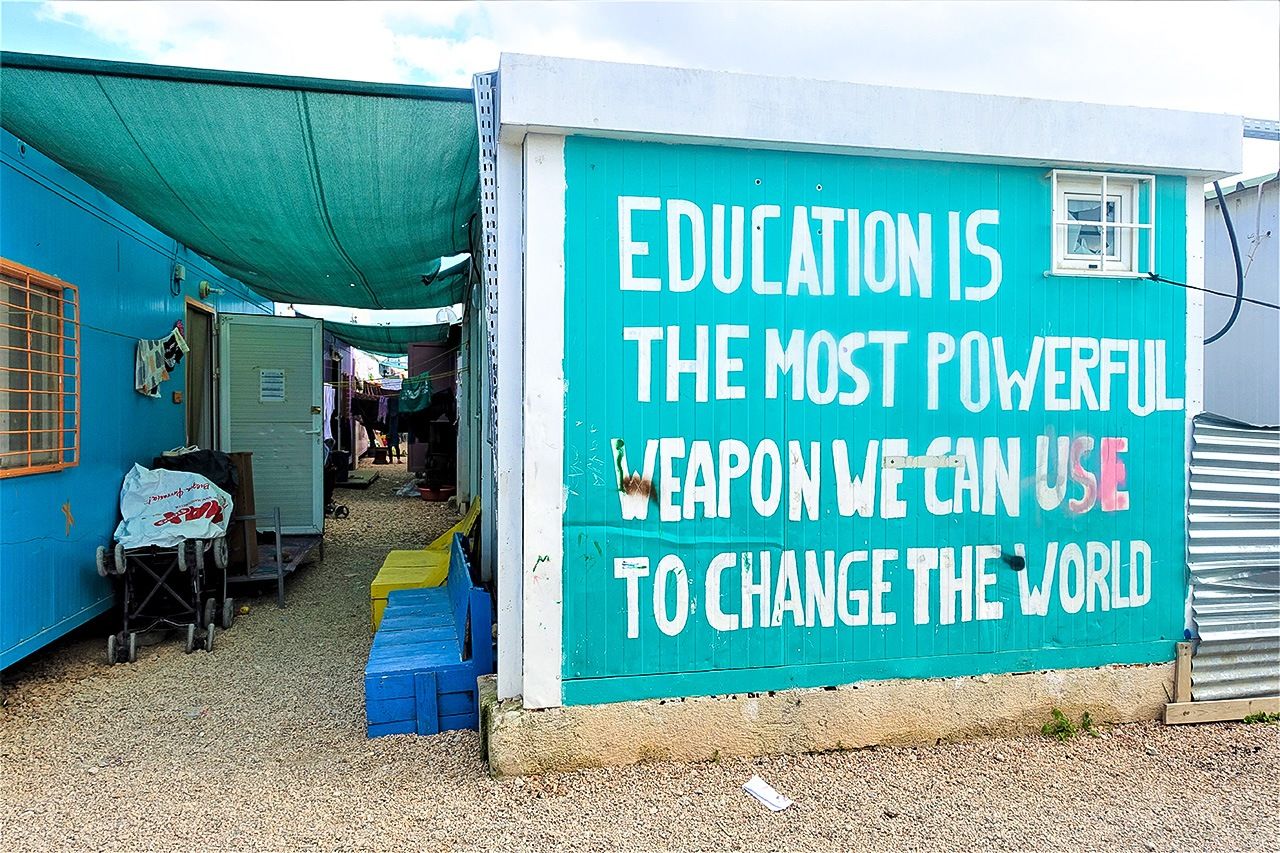

A slogan on the wall of a temporary dwelling inside the Elaionas refugee camp. (Photo by the author)

The Medal Podium of Life

It was swimming that taught Imoto about the world, made her friends, developed her communication skills, and ultimately led her to her present career. Her experience stands as an example for other amateur athletes exploring career choices after retirement.

Imoto accepts the Olympic flame on behalf of Tokyo from Hellenic Olympic Committee President Spyros Capralos during a ceremony on March 19, 2020. (© Jiji)

While Imoto never won a medal at the Olympics, now, in the professional sphere, she has her sights on a different kind of prize. Her clear vision from a young age about what she wanted to be and her drive to do what she needed to do to achieve that goal has enabled her to forge a successful career as an aid worker. I believe that any of us can achieve similar success if we put our minds to the task as Imoto did.

Two weeks after I visited Imoto at the refugee camp, Greece was dealing with a new problem. While the country was enforcing a curfew to prevent outbreaks of COVID-19, its refugee camps, in which large numbers of people live in close proximity and often in unhygienic conditions, had turned out to be a breeding ground for infection. Of greatest concern were those living in tents in refugee camps on the islands off the Aegean coast, on the border with Turkey. The crisis had stretched Imoto and her staff to the limits. When I talked to her on the phone, however, she sounded as cheerful as ever.

“When you think about it, as a swimmer, I aimed to be the best in the world,” she tells me. “In this career, I’m still only halfway to my goal. I want to address the inequities that stop children from going to school. I am working my hardest to make it to the top of this game as well.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Imoto Naoko helps children learning on tablets. Photo by the author.)