Aliens and Alienation: The Taboo-Challenging Worlds of “Earthlings” Author Murata Sayaka

Culture Art Books- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Back to the Convenience Store

Even after Sayaka Murata’s novel Konbini ningen (trans. Convenience Store Woman) won the Akutagawa Prize in 2016, for a while she returned to the convenience store job that had inspired it. She quit due to the physical strain, but says that she still finds herself thinking like an employee when she enters the familiar environment.

In these pandemic times, when going out typically means straying not much further than the local konbini, she has witnessed painful scenes. “Once, a customer was yelling at the clerks, ‘Why don’t you have masks for sale?’ and another time someone was asking accusingly, ‘Where did you get your masks from?’ I’ve felt bad at being the only one in a safe situation, while the staff are exposed to this threatening behavior, and considered whether I should become a store assistant again.”

Convenience Store Woman became a big hit in its English translation by Ginny Tapley Takemori, and versions have also appeared in several other languages. The protagonist Furukura is seen as odd from an early age because she does not show her feelings in the same way as others. While at university, she starts working part-time at a convenience store and through following the manual to the letter, she pretends to be a “normal person.” By the time of the novel, she is 36, unmarried, and still working at the store.

Murata herself had a part-time job at a convenience store for many years starting when she was a university student, although this was to add structure to her writing life. “The evening before days at the store, I’d make a to-do list for the following morning. It felt like having a small deadline every day, and that became a rhythm. Without a routine, I’d just be playing endlessly in unreal worlds.”

She wrote from two in the morning until six, did her job at the store from eight until one in the afternoon, and wrote again while she ate her lunch. As she was writing, she would polish up the world of the story by drawing caricatures of the characters and noting down conversations and scenes as she thought of them on white copy paper. When she quit her job, she lost that rhythm, and for a time was almost unable to write at home, working instead at cafés and the publishing house canteen.

The Reasons for Taboos

Those who only know Murata for Convenience Store Woman might get a shock from reading her other works.

In her previous novel, the 2015 Shōmetsu sekai (Dwindling World), sex between married couples is reviled as a form of incest, and women—and men—become pregnant and give birth artificially. Her first book after Akutagawa success was the 2018 Chikyū seijin, published in the English translation Earthlings (also by Takemori) in October 2020. It is even more extreme. The main character is a girl who does not get on with her family, believes that she is an alien unable to adapt to earth, and is in love with her cousin—also an “alien.” It appears at first to be a girl’s coming-of-age story, before veering into the unexpected territory of sexual abuse, murder, and cannibalism. The short story “Satsujin shussan” (Birth Murders) imagines a world in which women can choose to become “bearers,” and if they give birth to 10 children, are allowed to kill a person of their choice with no consequences. “Seimeishiki” (Ceremony of Life), another short, depicts a new kind of funeral in which the dead are eaten. Daring in construction, many of her works have elements of science fiction.

Murata began writing when she was in elementary school and dreamed of penning novels for girls. At the same time, she thought ceaselessly about how to find the real truth of things.

“I was the kind of child who liked pondering over different questions. I couldn’t understand why my parents provided me with food. They’d say it was because we were a loving family, but I couldn’t accept that answer.”

She had her doubts about various “unthinkable” actions. “For example, murder is said to be taboo, but then why is it considered acceptable if it’s legitimate self-defense or capital punishment? I sensed the ambiguity in my childish mind. And I felt a physical repulsion and fear inside me toward incest and cannibalism, although I didn’t know why they were forbidden. I wondered where those emotions came from.”

As she kept creating new stories, she wanted to experiment with a profound questioning of taboos. She thought it might be a way of getting closer to the real truth of things that she had been seeking since early childhood. She also says her writing gradually helped win her some freedom. “If I hadn’t written fiction, I think I’d still be struggling. Even now, every time I write a story, it feels like I’m chipping away at the preconceived ideas that constrain me.”

Living Through It

From her youngest days, Murata felt excessively restricted by being a girl. Her mother wanted her to learn the piano, wear neat dresses, enroll at a traditional women’s university, and have a suitable man fall in love with her at first sight before getting married. “There was great pressure that this is how girls should be.”

As an elementary school student, Murata was greatly affected by reading the novel Poil de carotte (trans. Carrot Top) by French writer Jules Renard. “I hated simplistic children’s stories where, because mothers love their children, there was always a happy ending. So I felt so comforted that Carrot Top was hopeless all the way through. Here was a writer with more dark places than me, and he wrote them all out without a word of a lie. It was the first time I felt close to an author.”

Junior high school was a rough time for her, and Murata says that she thought about killing herself. “I was ignored by a girl I’d been friendly with at first, and was excluded from her group. After she’d said nice things about how funny and interesting I was, she started telling me to go to hell. For a time, I thought I could accuse her through my suicide, but I figured that even if I died, she’d probably laugh at my funeral. So in the end, I wanted to live. I was writing fiction then, too, giving me another attachment to life. Whatever happened, I felt the most important thing was to live through it.”

Having somehow made it through her painful junior high days, she moved on to high school, where she started reading novels by Yamada Amy. “I’d always been shy, but I hardly talked with boys in particular. Reading Yamada’s books in high school, I realized my body was my own and not there for men’s ‘love at first sight.’ I could choose a boy myself and have sex through my own volition—I thought for the first time of sexual love as something that belonged to me.”

Freed from ideas of what a girl should be, Murata was newly able to talk with boys. But captivated by Yamada’s prose, she became self-conscious about her own sentences, entering an artistic slump. It was not until she was a university student that a local creative writing class provided the impetus for her to return to fiction.

A Magical Girl into Adulthood

The message of Murata’s fictional worlds is the importance of survival, no matter what challenges come, while battling the pressures of society’s ideas of normality, common sense, and justice.

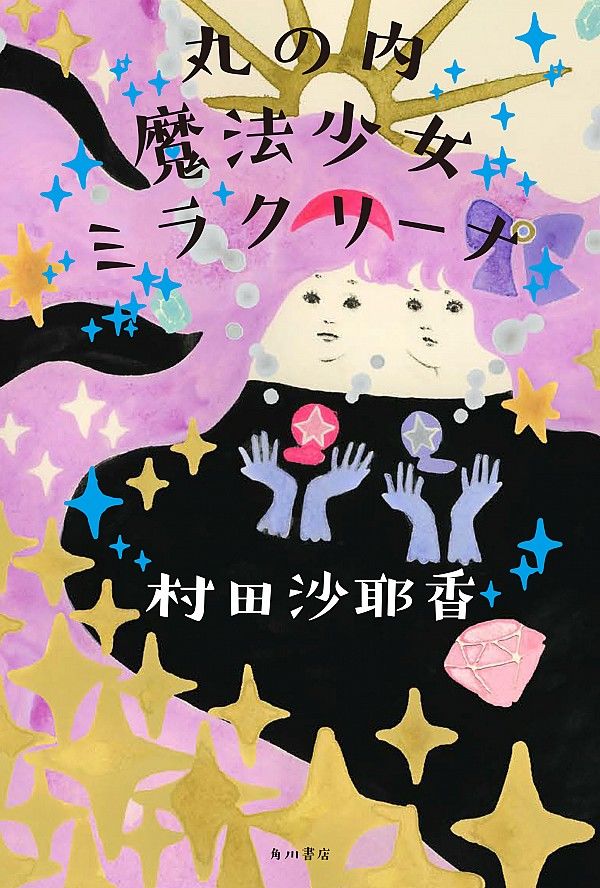

The title story of her February 2020 collection Marunouchi mahō shōjo Mirakurīna (Mirakurīna the Marunouchi Magical Girl) was first published in a magazine in 2013. It depicts an office worker in her thirties who escapes the trials of the everyday world by imagining herself using a miraculous cosmetics compact to transform into a “magical girl.” One day, a friend from elementary school days, another magical girl she had teamed up with to battle a nefarious organization, comes to ask for her help.

Marunouchi mahō shōjo Mirakurīna (Mirakurīna the Marunouchi Magical Girl). (Courtesy Kadokawa Shoten)

“I was greatly influenced by favorite childhood anime like Majokko Megu-chan [Megu, the Little Witch] and Mahō no tenshi Kurīmī Mami [Magical Angel Creamy Mami]. I wanted to write about a woman who continues as a magical girl, even as an adult.” Murata revisits the motif in Earthlings, where the protagonist gets through the pains of reality with the delusion that she is a magical girl from another planet.

“I wanted to write more about magical girls, so this was why I made the main character in Earthlings one. Mirakurīna finished more happily than I expected, but I didn’t think Earthlings would end with so much violence. I was shocked while I was writing, but it also made sense to me.”

Murata has never planned the endings of her fiction. “They change while I’m writing, like chemical reactions are taking place. I don’t really trust the ‘Murata’ who lives in human society. She only looks at things with eyes biased by imprinting and brainwashing. I still write with the belief that through my stories I’m traveling to the real world that I can’t see for myself.”

Her latest Japanese collection is quintessential Murata, filled with variety and tackling difficult topics with deceptively simple prose. “Himitsu no hanazono” (Secret Flower Garden) portrays a female university student who confines her first love for a week, “Musei kyōshitsu” (Gender-Free Classroom) depicts love among high school students when revealing one’s gender is forbidden, and “Hen’yō” (Transformation) centers on a 40-year-old woman, adrift in a society where anger is fading away alongside interest in love and sex.

Unexpected Sympathy

Murata’s supporting characters can make a strong impression. She says she always begins by drawing pictures of the people in the story. While she dreams up their age, gender, hairstyle, and clothes, she imagines such matters as what kind of childhood they had, and the characters gradually fall into place. She also takes unconscious hints from whoever happens to be around her in her daily life.

“If I write in a café, for example, I get a glimpse of people’s true feelings, like if a man reveals a terrible contempt for women, or if someone is talking about her search for a marriage partner and it seems to be really hard going. I think I unwittingly put those impressions in cold storage. Then when I start writing, those various expressions and small hints at inner feelings get defrosted, and I sense them entering into the characters.”

Sometimes minor characters can build up their roles. Shiraha, who in Convenience Store Woman joins Furukura as a part-time worker, is a classic example. He is a misogynist who blames the failures in his life on the shortcomings of the world, and looks down on Furukura. This unpleasant personage is fired for stalking a customer, but shows no signs of reflection.

“When I was drawing his caricature, Shiraha was set to be a bit part who’s sympathetic because he’s treated harshly by other workers. But when I started writing, he developed a terrible personality and became a main character. I was surprised by how many female Japanese readers said they couldn’t hate him because they understood his feelings as an outcast. As translations came out overseas though, he was overwhelmingly disliked, so only Japan was on his side.”

Follow the Story

While Convenience Store Woman was winning plaudits in countries like the United States, Britain, Germany, France, South Korea, and Taiwan, Murata was constantly making trips to literary festivals. Friends would ask her, “When are you going to be in Japan?” Versions continue to appear in other languages, such as Turkish, Arabic, and Hebrew. Now, Earthlings has been published in English.

“Ginny Tapley Takemori, who translated Convenience Store Woman suggested Earthlings as a follow-up. I was nervous about whether it would be OK to translate as it’s a really grotesque story. But Ginny sent the plotline to publishers in the West, who decided to take it on.”

Someone familiar with publishing in Europe and the United States told Murata that the foreign readers who’d enjoyed Convenience Store Woman might turn their backs on the new work. She is partly looking forward to and partly dreading reactions from the English-speaking world.

“With Convenience Store Woman, I was moved by the loving care with which Ginny and other translators and editors produced the translations, and the opportunity to communicate with foreign readers. It’s when it’s read that a work becomes complete, so I’m always excited when my books reach readers around the world. While writing, though, authors should only follow where the story takes them. All I can do is keep searching for words and go on writing as I want to write.”

Murata Sayaka, at Kadokawa’s head office in Tokyo in September 2020.

(Originally published in Japanese on October 23, 2020. Interview and text by Itakura Kimie of Nippon.com. Photographs by Hanai Tomoko.)

convenience stores literature translation books novels author