A Guide to City Pop, the Soundtrack for Japan’s Bubble-Era Generation

Culture Entertainment Music- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Roots of the Genre

City pop’s sophisticated sound, polished melodies, and lyrics of mature, urban romance have been making a comeback. And the Japanese genre’s revival has spread beyond its native shores. Around the world, there are fans keen to build up their collections, and more musicians and DJs are playing its classic songs.

Although there is no clear agreement, many point to the band Sugar Babe as crucial to city pop’s creation. Members Yamashita Tatsurō and Ōnuki Taeko would go on to be central figures in the musical style. Sugar Babe’s fusion of elements from oldies, singer-songwriter pop, and soul set it apart from contemporary rock bands influenced by hard and blues rock. From the time it formed in 1973, it offered an alternative to the mainstream, but was not truly appreciated until after splitting up just three years later. Yet the group’s members and the musicians around them paved the way for city pop.

Arai Yumi’s Cobalt Hour (1975) has a strong city pop flavor.

Matsutōya Yumi (then Arai Yumi) developed the template further. She started out in 1972 as a singer-songwriter and pianist. However, through collaboration with the band Caramel Mama, which formed the following year, she began to approach city pop territory, blending mature lyrics with a rich sound. Caramel Mama consisted of her future husband Matsutōya Masataka on keyboards, along with Suzuki Shigeru on guitar and Hosono Haruomi on bass—both guitarists former members of the influential folk rock group Happy End—and Hayashi Tatsuo on drums. It is no exaggeration to say that the band perfected the city pop sound.

Caramel Mama changed its name to Tin Pan Alley and released its own albums, but was mainly a support group for a host of artists. It was involved with the creation of 1970s albums by many classic city pop singers including Kosaka Chū, Yoshida Minako, Yano Akiko, Minami Yoshitaka, and Sugar Babe’s Yamashita Tatsurō and Ōnuki Taeko. As the backing group for big-name singers like Minami Saori and Ishida Ayumi in the more standard kayōkyoku pop genre, it also brought the city pop sound into the nation’s living rooms.

The Golden Age

City pop did not really break through, however, until the 1980s. Yamashita Tatsurō’s single “Ride on Time” made waves and Takeuchi Mariya had a big hit with “Fushigi na pīchi pai” (Mysterious Peach Pie) in 1980. The next year, “Pegasasu no asa” (Pegasus Morning) by Igarashi Hiroaki and “Surō na bugi ni shite kure (I want you)” (Make It a Slow Boogie [I Want You]) by Minami Yoshitaka rode high in the charts. But the song that really sent the genre soaring was Terao Akira’s “Rubī no yubiwa” (Ruby Ring). Steeped in the dandyish outlook of a lonely urbanite, the megahit single racked up sales of more than 1.6 million, winning cross-generational affection. At the same time, it propelled city pop into the Japanese musical mainstream.

Yamashita Tatsurō’s Ride on Time (1980) and Terao Akira’s Reflections (1981), which features the hit song “Rubī no yubiwa” (Ruby Ring).

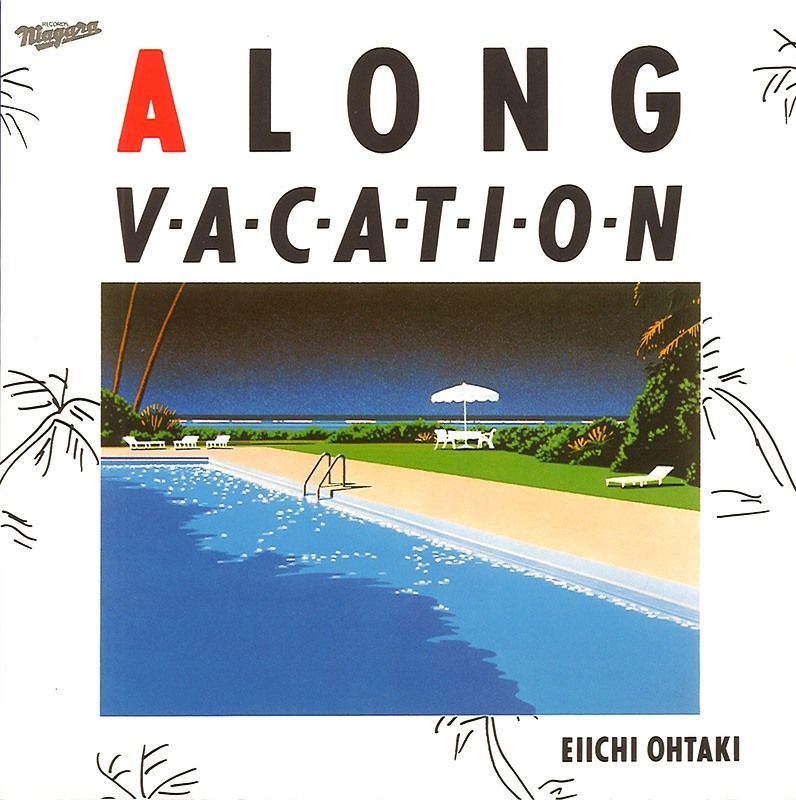

Ohtaki Eiichi’s A Long Vacation (1981).

City pop entered a golden age. Adult-oriented artists like Kisugi Takao, Sugiyama Kiyotaka and Omega Tribe, Nakahara Meiko, and Anzen Chitai became regulars on television. Idol acts such as Matsuda Seiko, Yakushimaru Hiroko, and Kikuchi Momoko took on city pop influences. Veterans of rock and folk Yazawa Eikichi and Inoue Yōsui dabbled in the genre for new hits. Other talented performers like Kadomatsu Toshiki, Sugi Masamichi, Inagaki Jun’ichi, and Stardust Revue were also active in this period.

Yet city pop’s position as the new standard signaled its slow decline as a musical movement. The genre’s artists gained less attention as the “idol boom” and “band boom” sent pop and rock, respectively, in new directions. Still, the big stars continued to perform and the emergence of the major 1990s Shibuya-kei genre prompted reappraisal of city pop mainstays like Matsutōya Yumi and Ohtaki Eiichi. As Shibuya-kei itself began to fade at the end of the decade, acts like Kirinji and Kinmokusei laid the foundations for a revival in the form of neo city pop.

A New Wave of Interest

The 2010s city pop revival was a natural development, taking place as the music scene diversified, and there were no longer clear genre boundaries. It became usual for musicians to move between, for example, rock, folk, and R&B, so it was only a matter of time before interest turned once more to city pop.

Neo city pop artists from the 2010s including Cero, Yogee New Waves, and Awesome City Club are mainly rooted in the indie club scene. Producer Kunimondo Takiguchi, who has worked with singer Hitomitoi, is another key presence. The band Suchmos, which got its break when its song “Stay Tune” appeared in a commercial, further expanded the possibilities of the genre.

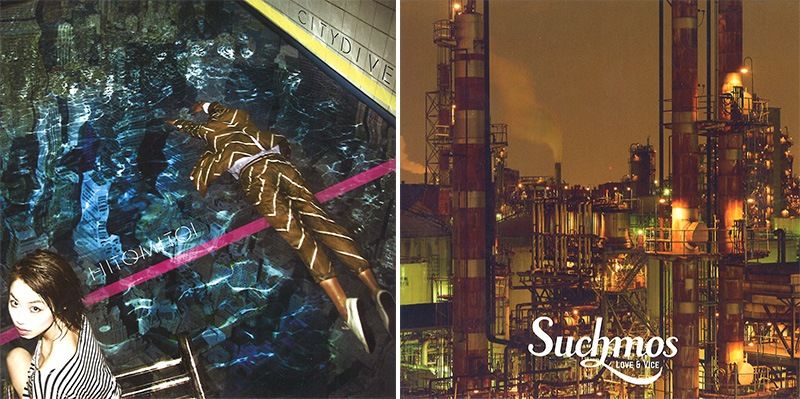

Hitomitoi’s City Dive (2012) and the Suchmos EP Love & Vice (2016), which includes the band’s breakthrough song “Stay Tune.”

DJs also played an essential role in the renewed interest in city pop. From the Shibuya-kei era in the 1990s, it had been common for them to sample artists like Yamashita Tatsurō and Yoshida Minako. From around 2010, a craze for stylish disco tunes prompted DJs to reinvestigate disco-influenced 1980s city pop. They began by unearthing artists like Kadomatsu Toshiki and Matsubara Miki, but their characteristic penchant for deep cuts led them to give more obscure performers like Tōyama Hitomi, Mamiya Takako, and Aran Tomoko time on their turntables.

International Fans

The city pop wave subsequently spread overseas. In the 2010s, there are more ardent music fans around the world seeking hard-to-get-hold-of Japanese albums, not only through online auctions but also by making a trip to Tokyo. I remember recently people talking about a foreign fan who appeared on television saying that he wanted to buy Ōnuki Taeko’s Sunshower. There are also a lot of tracks uploaded on services like YouTube and Soundcloud. For instance, Takeuchi Mariya’s song “Plastic Love” racked up more than 20 million views on YouTube after it was initially posted in July 2017.

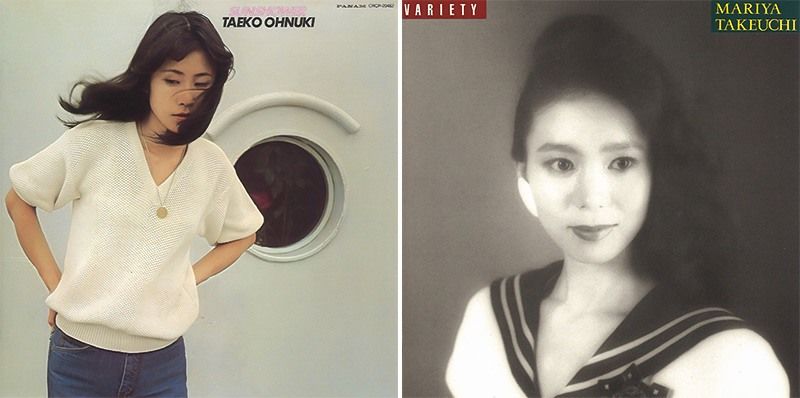

Ōnuki Taeko’s Sunshower (1977) and Takeuchi Mariya’s Variety (1984), which includes her Internet-famous song “Plastic Love.”

International musicians have also shown their appreciation of city pop. US DJ and sound creator Toro y Moi is probably the best example. Brazilian singer-songwriter Ed Motta collects Japanese records, and covered Yamashita Tatsurō’s “Windy Lady” when he performed in Japan. The bands Ikkubaru of Indonesia and Polycat of Thailand both acknowledge the great influence of the genre, and have brought their versions of it back to Japan.

Many of the generation that listened to city pop in real time associate it negatively with the abortive sparkle of the bubble era. Young people today, however, can simply enjoy it as a fresh mix of musical elements that is continuing to develop. Japanese music has lost the unfashionable tag of past eras, and city pop is winning interest as a cool new genre.

(Originally published in Japanese on December 21, 2018. Banner photo: A selection of classic city pop albums from the 1970s and 1980s.)