Engineering Defense at Japan’s Mountain Castles

History Culture Guide to Japan- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

There are 30,000–40,000 castle ruins across the Japanese archipelago, built from the early fourteenth to the early seventeenth century. By global standards, this is a huge number for a span of around 300 years. The Warring States period (1467–1568) in particular was an age of major fortress construction.

The classic image of a Japanese castle for many is of a gleaming white keep surrounded by high stone walls and a deep moat. Yet the first structure to resemble this archetype was Oda Nobunaga’s Azuchi Castle, for which construction only began in 1576. The castles of the Warring States period were entirely different, mostly adapting themselves to mountainous terrain.

Civil Engineering for Defense

In the early days, a mountain castle (yamajiro) for last-ditch defense was combined with residences in the foothills. In other words, people did not live in the castles themselves. The Ichijōdani Asakura Clan Ruins in Fukui Prefecture—now a tourist spot—are actually the remains of the lower residences, rather than the great castle higher up the mountain.

The Ichijōdani Asakura Clan Ruins in Fukui Prefecture.

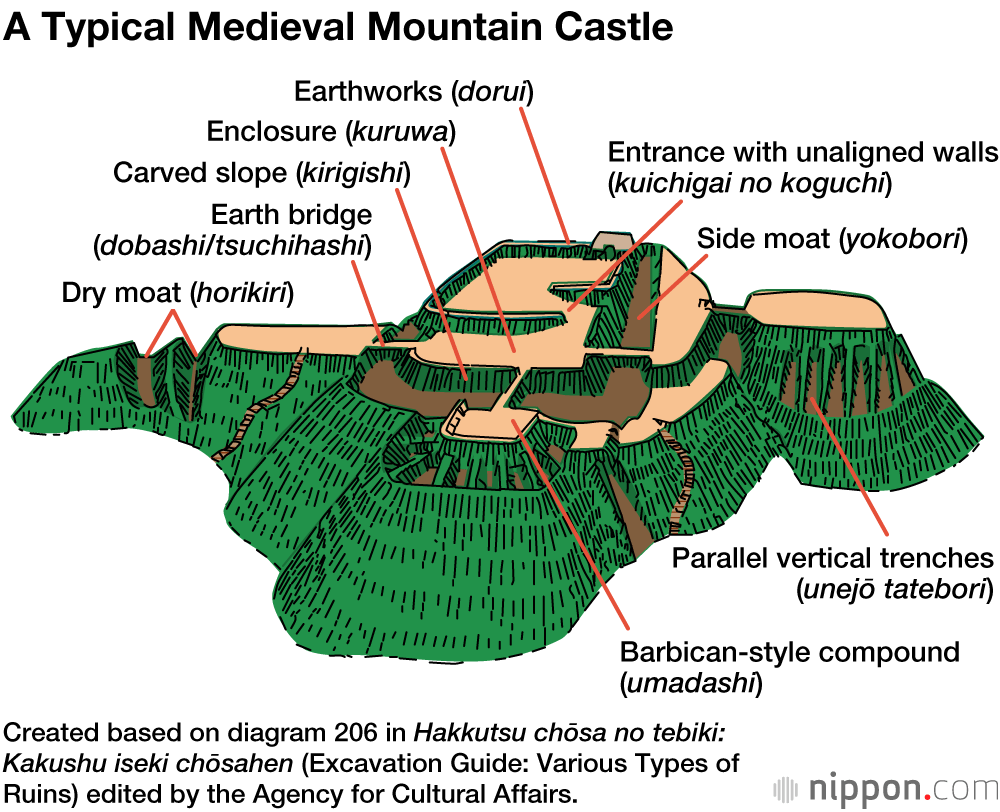

Yamajiro were carved out of the mountainside. Workers created a flat area known as a kuruwa, cut away at the sides of ridges with large knives to form dry moats (horikiri), and used the earth accumulated during these tasks to build earthworks (dorui). Warring States period castle construction was more like civil engineering than architecture.

Warriors were stationed in the kuruwa, which would usually have just two or three small buildings held up by pillars embedded directly in the ground instead of using foundation stones. These were surrounded by earthworks that were thicker at the corners to support simple turrets made of wood.

The kuruwa at the ruins of Jōheiji Castle in Shiga Prefecture.

The horikiri dry moats protected the rear of castles built at one side of a hill from attack from nearby ridges. Often one was considered sufficient, but in some cases there might be multiple moats in succession.

The horikiri at the ruins of Iimori Castle in Osaka Prefecture.

Another key structural feature was the kirigishi, slopes around the kuruwa that were made artificially steep. As mountain castles put attackers at a disadvantage by forcing them to climb, the sheer kirigishi were more important than any of the other elements mentioned so far. At Chiran Castle and Shibushi Castle in Kagoshima Prefecture, slopes carved almost vertically in the volcanic soil are more than 20 meters high, and must have been unclimbable.

The kirigishi at the ruins of Shibushi Castle in Kagoshima Prefecture.

Upgrading Defense

In the second half of the Warring States period, upgrades helped to strengthen mountain castles. By making the earthwork walls around the kuruwa curved rather than straight, it became possible to attack the advancing enemy from the sides as well as the front. Side attacks were also common on soldiers entering through the koguchi or castle entrance.

Curved earthwork walls at the ruins of Katsuga Castle in Kagawa Prefecture.

This koguchi also saw many adaptations. It began as a simple opening in the earthwork walls, but in a later development known as the kuichigai no koguchi, the walls were no longer aligned. This meant that people coming into the kuruwa had to turn to enter, meaning attackers could not simply charge straight forward.

A kuichigai no koguchi entrance at the ruins of Matsuoyama Castle in Gifu Prefecture.

The next stage was to create a square enclosure just inside the castle entrance, where defenders could assail intruders with arrows from three directions. This masugata koguchi design was also incorporated into the following generation of castles, and can be seen today in many ruins.

Another innovation was the umadashi, a flat space connected to the central kuruwa by earth bridges over the main moat, which further protected the entrance from direct attack. Semicircular types were used by both the Takeda and Tokugawa clans. All of the entrances to Suwahara Castle in Shizuoka Prefecture had one of these umadashi in front of them. Meanwhile, the Hōjō clan and many castles in Kantō used the squared-off type.

A semicircular umadashi at the ruins of Suwahara Castle in Shizuoka Prefecture.

Dry moats were improved with the addition of unejō tatebori, parallel trenches dug vertically into the kirigishi slopes. These are thought to have prevented enemy soldiers from moving up the slopes diagonally. Nagano Castle in Fukuoka Prefecture was surrounded by almost 200 of these trenches.

Unejō tatebori at the ruins of Nagano Castle in Fukuoka Prefecture.

The use of embankments within moats also limited enemy movement. They might create a lattice-like pattern called horishōji that was difficult to cross. At the Hōjō clan’s Yamanaka Castle in Shizuoka Prefecture, both trenches in moats and horishōji were constructed extensively around 1587, in preparation for an attack by the warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

Horishōji at the ruins of Yamanaka Castle in Shizuoka Prefecture.

Stone Walls and Residences

In the early sixteenth century, from Nagano and Gifu Prefectures to northern Kyūshū, mountain castles increasingly had stone walls. These were only generally used within a part of the inner castle, however, and did not exceed four meters in height. By the middle of the century, though, Kannonji Castle in Shiga Prefecture was built entirely with stone walls, with some over five meters high. Many of the stones used were more than a meter long. Techniques applied to temple architecture were used in constructing the walls.

A high stone wall at the ruins of Kannonji Castle in Shiga Prefecture.

The daimyō Miyoshi Nagayoshi (1522–64) enthusiastically adopted stone walls, constructing them between ridges at Akutagawasan Castle and covering much of the ground at Iimori Castle in Osaka Prefecture.

A wall made of large stones at the ruins of Iimori Castle in Osaka Prefecture.

In Miyoshi’s castles, the residences are thought to have been up in the mountains rather than the foothills. An excavation at Akutagawasan Castle discovered the foundation stone for a residence in the main compound at the top of the peak. In the second half of the Warring States period, the mountain castles of daimyō in general shifted away from the earlier split form, with warriors living below the castle, to a unified form in which they lived on the mountain proper. Their families apparently accompanied them. The remains of large buildings have also been discovered at Odani Castle and Kannonji Castle in Shiga Prefecture.

Odani Castle in Shiga Prefecture, where stones for residences were discovered in an excavation, indicating that families lived there.

Many say that if one visits a mountain castle today, there is nothing to see. Yet the remains of defensive features like the kuruwa, dorui, and horikiri are clearly visible, making it possible to experience something of the atmosphere of the Warring States period. It is the most thrilling of feelings. One wishes to stand in the ruins and look around at what its defenders would have seen. There must have been the villages and other territory, roads, rivers, coastlines, and even enemy fortresses. These visible aspects of terrain and manmade structures speak a historical truth about the reason for the castle’s placement.

(Originally published in Japanese on September 18, 2019. Banner photo: A lattice-like pattern of moats and embankments at the ruins of Yamanaka Castle in Shizuoka Prefecture. © Pixta. All other photos courtesy Nakai Hitoshi.)