Cholera Outbreaks and Public Health in Modernizing Japan

Health History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Cholera in Japan

In the sixth century, Japan suffered a major smallpox epidemic. The disease would regularly return in following centuries, as would outbreaks of measles, to claim many lives. However, Japan was not affected by such wide-ranging scourges as the plague and yellow fever until it was embroiled in a global pandemic for the first time with the arrival of cholera in the nineteenth century.

Cholera was endemic in the Ganges Delta, but as Britain brought India under its control and traded across Asia in the early nineteenth century, the disease spread worldwide. The severe diarrhea and vomiting it caused resulted in death by dehydration. Cholera arrived in Japan in 1822, and is thought to have traveled from China via the Ryūkyū islands to Kyūshū. It then crossed to Honshū, killing large numbers of people in western Japan, but failed to reach as far as Edo (now Tokyo).

It was not until 1858 that Edo—at that time one of the largest cities in the world, with a population of over 1 million—faced a cholera outbreak. It is said to have been transmitted from crew members of the USS Mississippi, part of Commodore Matthew Perry’s US Navy fleet, during a stop at Nagasaki after a journey via China. This was the year that Japan was forced to sign five unequal treaties, including the Treaty of Amity and Commerce with the United States, which provoked increased anxieties among the population after over two centuries of limited foreign relations. One can imagine the panic caused by the spread of cholera at this time.

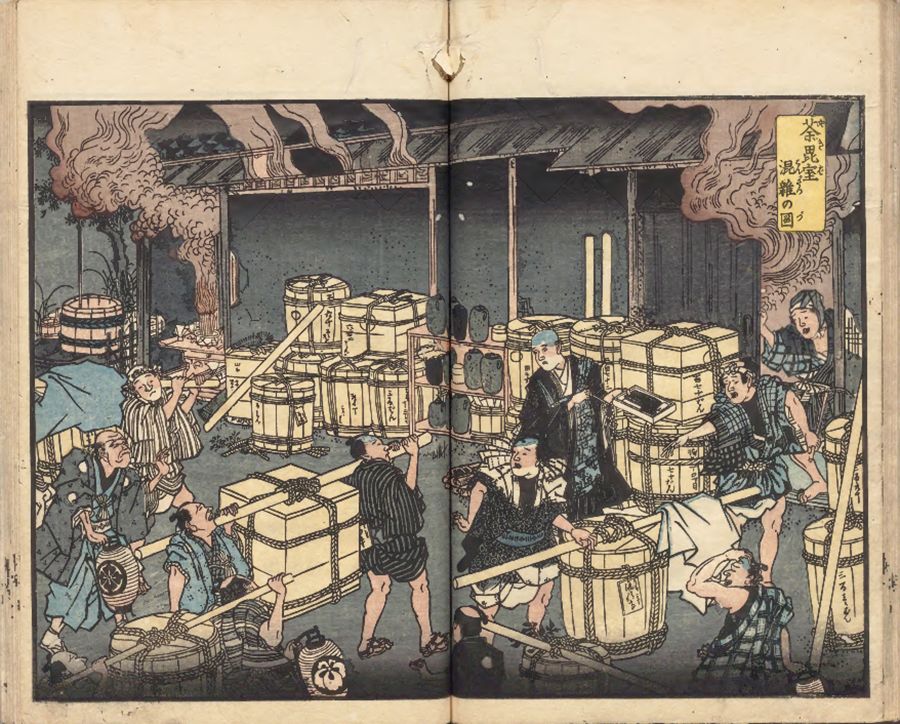

In contemporary records, fatalities in Edo were recorded somewhere between 100,000 and 300,000, and the ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Hiroshige is thought to have been among them. The coastal ships that were the main form of transport for goods at the time also took cholera to port cities in Tōhoku and other parts of the country. As Edo’s fatalities mainly took place in 1858, it is associated with that year, but in some areas more people died the following year.

Japan’s third major cholera outbreak came in 1862. While this is believed to have caused the most fatalities of the three, the 1858 outbreak is better known because it struck Edo most severely, where it was documented by many scholars, writers, and artists.

The frontispiece to the work Ansei korori ryūkōki (Record of the Ansei Cholera Outbreak) shows a scene with so many coffins, it is impossible to burn them all. (Courtesy National Archives of Japan)

Dangerous Beasts

Cholera became known by a range of different names around the country. In Japanese now it is called korera, but in the nineteenth century it was commonly korori, which also means “to die suddenly.” This is strangely close to korona, the abbreviation for the coronavirus.

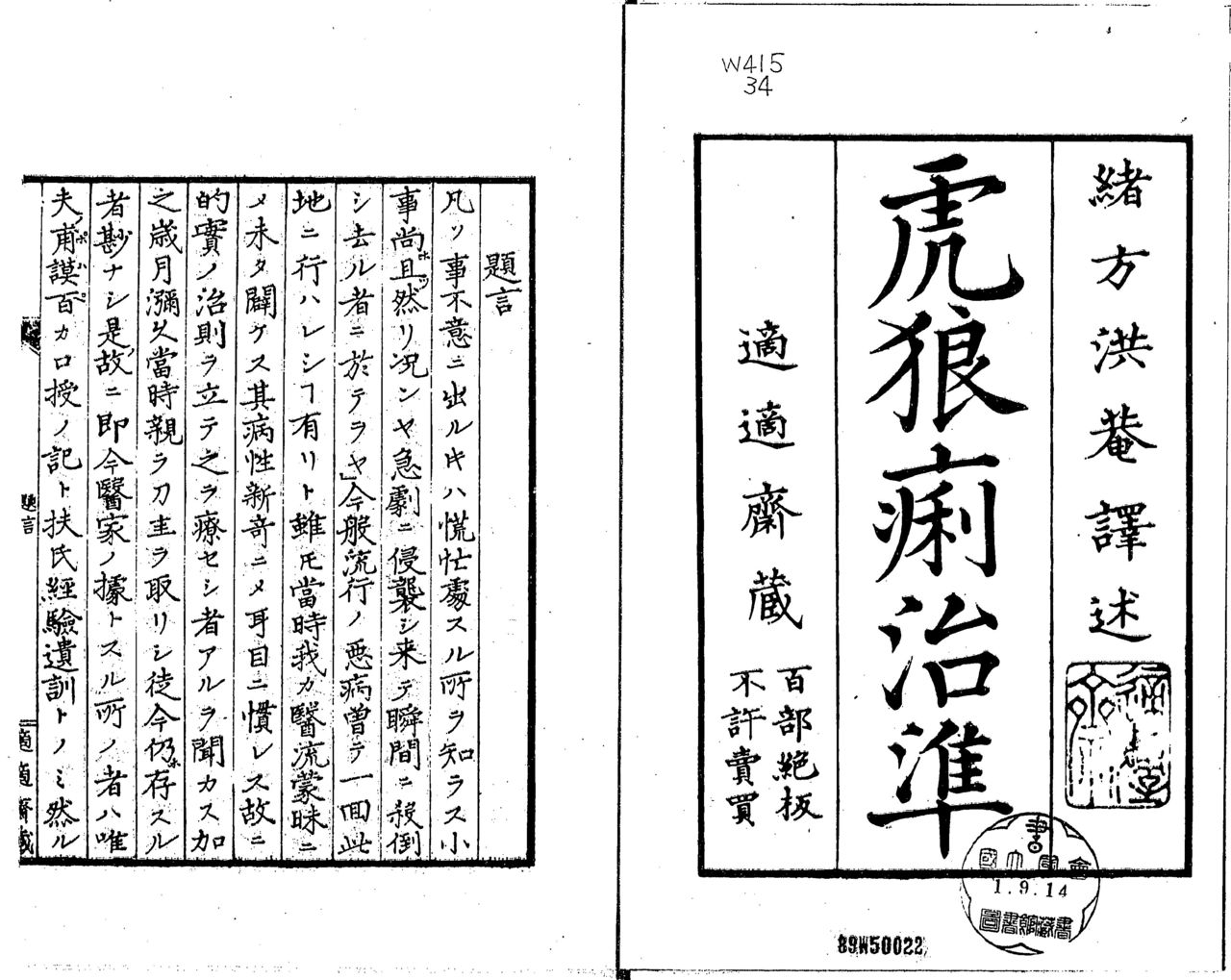

There was also a variety of ways to write the word in kanji, with one version, 狐狼狸, lining up characters for foxes, wolves, and tanuki (raccoon dogs)—the first and third of these are known in Japan as sometimes malicious tricksters. Another, 虎狼痢, emphasized ferocity with kanji for tigers, wolves, and diarrhea. This was used by Ogata Kōan, a well-known physician, in the title of his treatment handbook published in 1858.

Ogata Kōan created his treatment handbook Korori chijun (Guide to the Treatment of Cholera) based on abridgements of three foreign medical books. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

An 1886 nishiki-e multicolored woodblock print depicted cholera with the head and front legs of a tiger, the torso and back legs of a wolf, and the legendarily large testicles of the tanuki, to create a terrifying new beast.

In this picture, Korera taiji (The Slaying of Cholera), plum vinegar is presented as a miraculous medicine for overcoming the disease. (Courtesy Tokyo Metropolitan Archives)

A New Awareness of Public Health

Before the arrival of cholera, Japan had almost no medical responses to an epidemic. People resorted to prayer, sticking protective charms on their doors and staying inside, or beating drums and ringing bells to drive the sickness away.

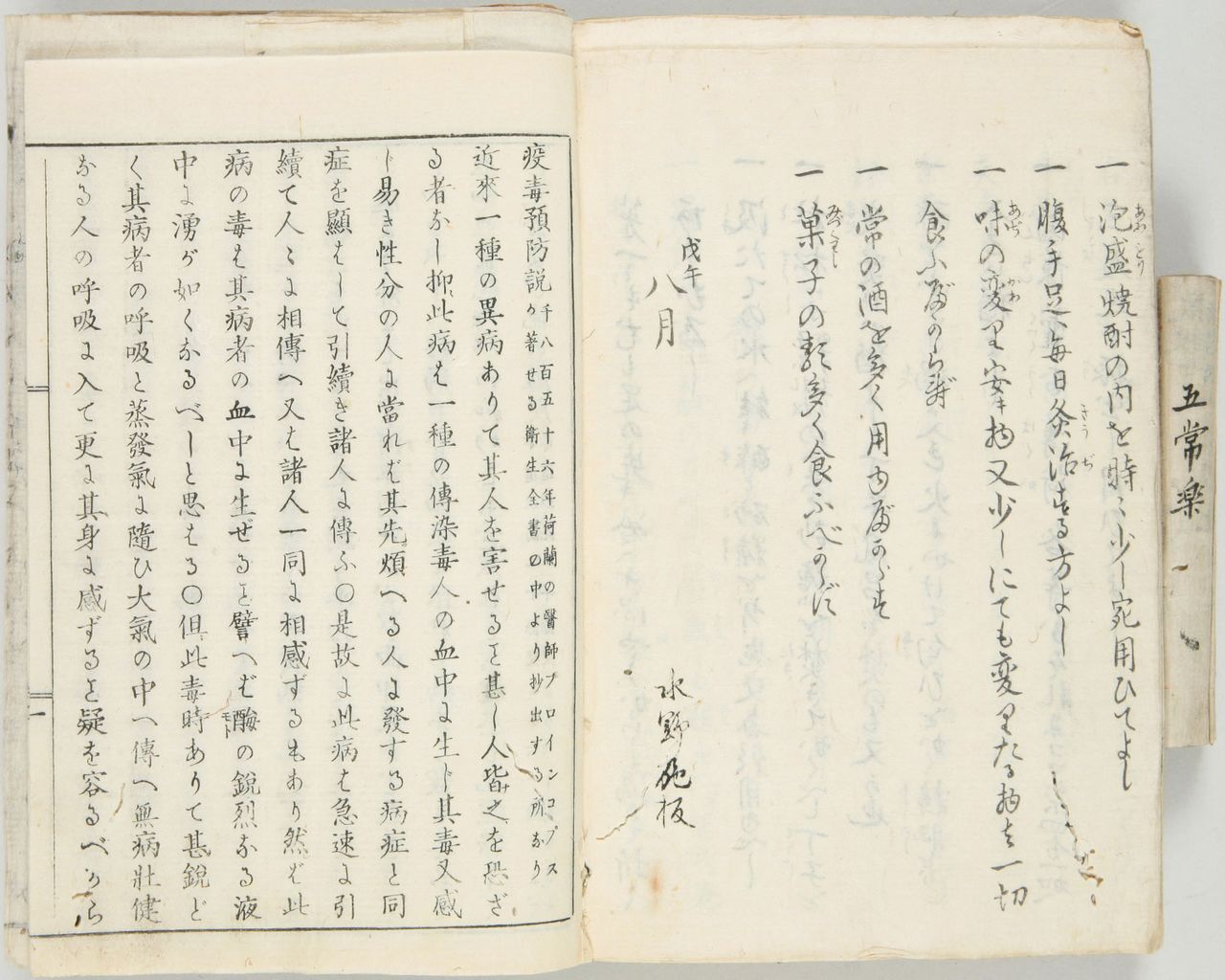

The treatment handbooks from Ogata and the Dutch doctor J. L. C. Pompe van Meerdervoort proved somewhat effective. The shogunate ordered a book published on the prevention of epidemics from its official institute for studying books in foreign languages. This was an abridged translation of a Dutch book on hygiene, which made such recommendations as “to keep one’s body and clothes clean,” “to keep rooms well ventilated,” and “to take a certain amount of exercise and eat and drink in moderation.”

A copy of Ekidoku yobōsetsu (On Prevention of Epidemics), a book ordered by the shogunate. (Courtesy National Archives of Japan)

There were also a number of cholera outbreaks in the Meiji era (1868–1912), including those of 1879 and 1886, each of which caused more than 100,000 fatalities. By this time, it was known that cholera was often spread through contaminated water and became more active in summer. More specific methods for combating the disease were “to not drink too much well water,” “to dry rooms out through ventilation,” and “to not eat raw or spoiled food.”

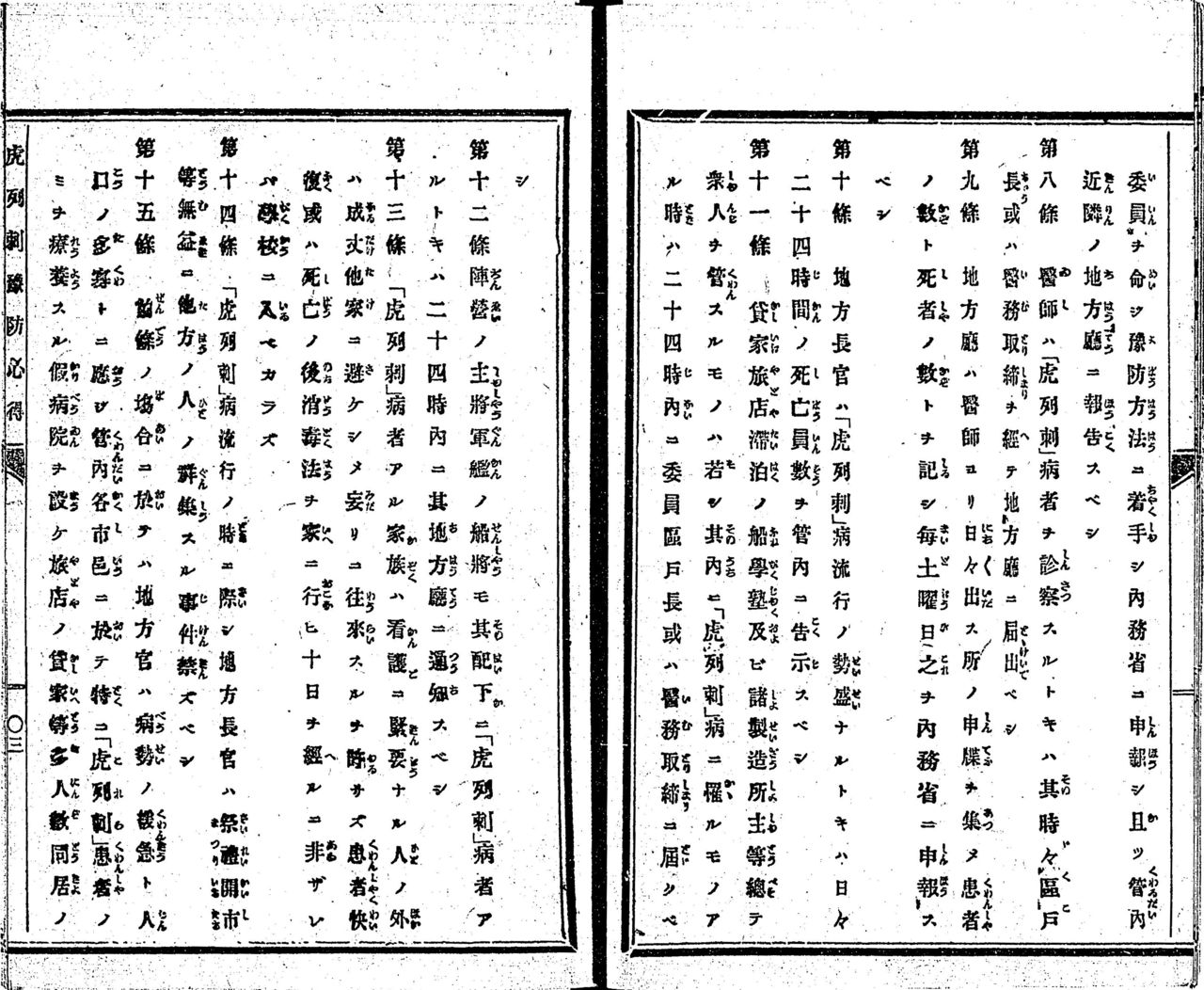

An 1877 document on the prevention of cholera from the Japanese leader Ōkubo Toshimichi included such methods as disinfecting with phenol and cleaning toilets and sewage pipes. One section said that in a household where a family member was sick, relatives who were caring for that person should not leave the home, while all others should quickly leave.

Infectious disease is said to be the mother of public health, and Japan’s cholera epidemics rapidly raised awareness of the importance of hygiene. While many aspects of the current coronavirus are different, it is not surprising that a number of prevention methods are the same. The people of the late nineteenth century lived buffeted by rumors, while striving to maintain cleanliness, remain indoors, and wait until the outbreak died down. This was all they could do. In an age when information and preventive goods are, by contrast, abundant, people today should appreciate the dangers of COVID-19 and take appropriate action.

Article 13 of Ōkubo Toshimichi’s Korerabyō yobō kokoroesho (Instructions on Cholera Prevention). It includes provisions that after a patient has died or recovered, the family should disinfect the house and members may not attend school until 10 days have passed. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

(Originally published in Japanese on April 5, 2020. Banner picture: Korera taiji (The Slaying of Cholera). Courtesy Tokyo Metropolitan Archives.)