Creating Serenity: The Construction of the Meiji Shrine Forest

Culture Environment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

This year marks the 100th anniversary of one of Tokyo’s most renowned landmarks, Meiji Shrine. Situated in the heart of the capital, the forested sanctuary was established on November 1, 1920, to enshrine Emperor Meiji (1852–1912) and Empress Shōken (1849–1914), who reigned during Japan’s transformation from a feudal empire to a modern state.

Shintō, Japan’s native animistic religion, in its original form considers all of nature to be divine. While the various gods, or kami, reside in all variety of natural phenomena—mountains, rivers, wind, and sea—forests are important elements of shrines as they are thought to contain the spirits of the tutelary deities of the sanctuary.

The Meiji Shrine, while dedicated to a deified emperor and not a natural kami, boasts an impressive chinju no mori, or “sacred forest,” that dominates the inner garden where the main hall is situated, providing an oasis of calm amid the bustling metropolis. Visitors walking under the expansive canopy can easily be lulled into thinking that they are strolling through a virgin forest, but the woods were carefully planned and planted by hand just a few generations earlier. The outer garden of the shrine, located several blocks away, is dedicated to cultural facilities like the Meiji Memorial Picture Gallery and sports grounds, but also has extensive wooded areas.

The Naien, or inner garden, of Meiji Shrine.

A Bold Project

Tokyo Mayor Sakatani Yoshirō and the industrialist Shibusawa Eiichi first put forward the idea of building a shrine to commemorate Emperor Meiji shortly after the monarch’s death in July 1912. The emperor had resided in Tokyo, but by custom, he was to be buried in Kyoto, the traditional capital. There was massive outpouring of support in the city and from around the country to establish a shrine where average citizens could pay homage to the virtues and spirit of the emperor, whom they had held in great esteem. This set in motion a national project to build a sanctuary to the emperor funded by the national government and through public donations.

In 1913, the government set to work on the project, establishing a committee to create a plan for the shrine. After considerable debate, the group selected a 70-hectare plot of land in the Tokyo suburb of Yoyohata-machi (present day Yoyogi) for the inner garden. The royal couple had frequently visited the site, taking walks in the fresh air and natural surroundings as a way to help maintain the empress’s health. A separate 27-hectare parcel of land where the emperor’s funeral hall had stood was chosen for the outer garden.

In 1915, the Interior Ministry established a shrine construction bureau to oversee the project, which in turn selected a team of experts for the building committee. The architect Itō Chūta and the architectural historian Sekino Tadasu of the Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo) were charged with the design and construction of central shrine structures including the main hall and the Meiji Kinenkan (also known as the Constitution Memorial Hall). Forestry experts Kawase Zentarō and Honda Seiroku were given the monumental task of planning the shrine forest, and Fukuba Hayato, a landscape artist for the Imperial Household Agency, and Hara Hiroshi, a professor of agriculture at the Tokyo Imperial University, oversaw the construction of green spaces in the outer garden.

Japanese Spirit, Western Learning

The leaders of the Meiji Shrine project recognized its importance to the country and worked to strike a balance between native aesthetic and modern Western elements. The inner garden, which opened in 1920, is designed as a Shintō space with a vast protective forest, broad paths for worshippers, and shrine buildings constructed from wood in the traditional nagare-zukuri architectural style characterized by long, asymmetric gabled roofs. The outer garden, finished in 1926, reflects Western architecture and landscaping ideas and contains the stone-built Meiji Memorial Picture Gallery with its prominent vista of arches, green spaces with symmetrical rows of trees, and athletic facilities dedicated to imported sports like rugby and baseball.

The construction of the shrine forest, one of the most ambitious components of the project, was headed by Honda, Hongō Takanori, and Uehara Keiji. Honda had studied forestry in Japan and Germany and was one of the premier scholars in the field. He had also made a name for himself as a lecturer on landscaping at the Tokyo Imperial University and as the designer of Hibiya Park, the first Western-style park in Japan. Hongō, a former student of Honda’s and also a professor at the Tokyo Imperial University, is credited with drawing up the plan for the long-term development of the shrine forest.

The third member of the planning team, Uehara, was a landscape architect who specialized in forest environments. While still a student, he expressed strong interest in the project from the outset and joined in on preliminary committee hearings. Authorities at the shrine construction bureau, impressed with his expertise and drive, ultimately tapped him to help lead the project.

Uehara would earn his PhD in forestry based on his involvement in the project and go on to be a leading force in landscape architecture in Japan. Following the opening of Meiji Shrine, he traveled to the United States and Europe to study Western landscaping, an experience that would deeply influence his views on urban development. Returning to Japan, in 1924 he established the first technical school of landscape engineering in the country (this would become the Faculty of Regional Environment Science at the Tokyo University of Agriculture), and the following year founded the Japanese Institute of Landscape Architecture. As Japan’s foremost expert on landscaping, he was a firm proponent of building urban green spaces, a view he advocated to authorities charged with rebuilding parts of Tokyo heavily damaged in the 1923 Great Kantō Earthquake.

Rather than building conventional parks, though, he emphasized the importance of creating “solemn” spaces where visitors could experience the essence of nature in its full and immutable form, finding manifestation of this concept in such native landscaping traditions as Japanese gardens, shrine forests, and imperial mausoleums. He spent his career propagating his pioneering ideas, publishing some 250 works and educating a new generation of landscape engineers.

Building an Eternal Forest

These three experts faced tremendous challenges in creating a tutelary forest in Tokyo that mirrored the untouched woods encircling Japan’s most ancient shrines. As a sacred space, it needed to be pristine as well as self-generating so as to last forever. This required the trio to construct an ecological strategy to transform the site, which was taken up mainly by fields and grassland and contained only eight hectares of wooded area.

Uehara played a central role in determining what species of trees to plant. He travelled to 88 historic Shintō shrines around the country to study their forest environments and was even allowed onto the grounds of the burial mound of Emperor Nintoku to observe the natural conditions. He was particularly influenced by the ancient kofun, a massive key-hole shaped grave surrounded by a man-made moat, and other imperial burial mounds at the site, finding in these clues to building a self-sustaining forest. He noted that these were artificial structures, but over time they had come to be shrouded in primeval woodlands that “for centuries have endured without even the slightest intervention by humans.”

The planners set out several conditions for developing the forest. First, it was important that it be unbroken, with trees covering the entire area of the shrine, except around buildings and where paths for worshipers would be, creating a majestic and tranquil environment. It was equally vital that the forest mature naturally without human intervention and that people, even the managers of the site, not be allowed to enter or otherwise disturb the ecosystem. They insisted that plant litter and fallen trees be left on the forest floor to decay, where they would act as fertilizer and support the growth of mushrooms and other fungi, further enriching the soil. Similarly, trees would be allowed to regenerate naturally from seeds without supplemental planting.

In creating their plan, the group did not try to copy a particular forest type, but selected hardy, indigenous species of trees and plants that were suited to Tokyo’s climate. Officials in the government and the Imperial Household Agency preferred that Japanese cedar and cypress be the dominant varieties. However, conditions were unsuitable for cedar, which required abundant water and was intolerant to the smoke and soot wafting in from the adjacent railroad. The group decided on a mixture of broad-leaf evergreens like camphor and oak and conifers like pine that would develop distinct canopy layers, similar to what Uehara had observed during his surveys.

In all, some 122,000 trees of 365 species were donated to the project, 95,000 from the public. These were shipped to Tokyo from around the country and transplanted by hand by roughly 110,000 volunteers.

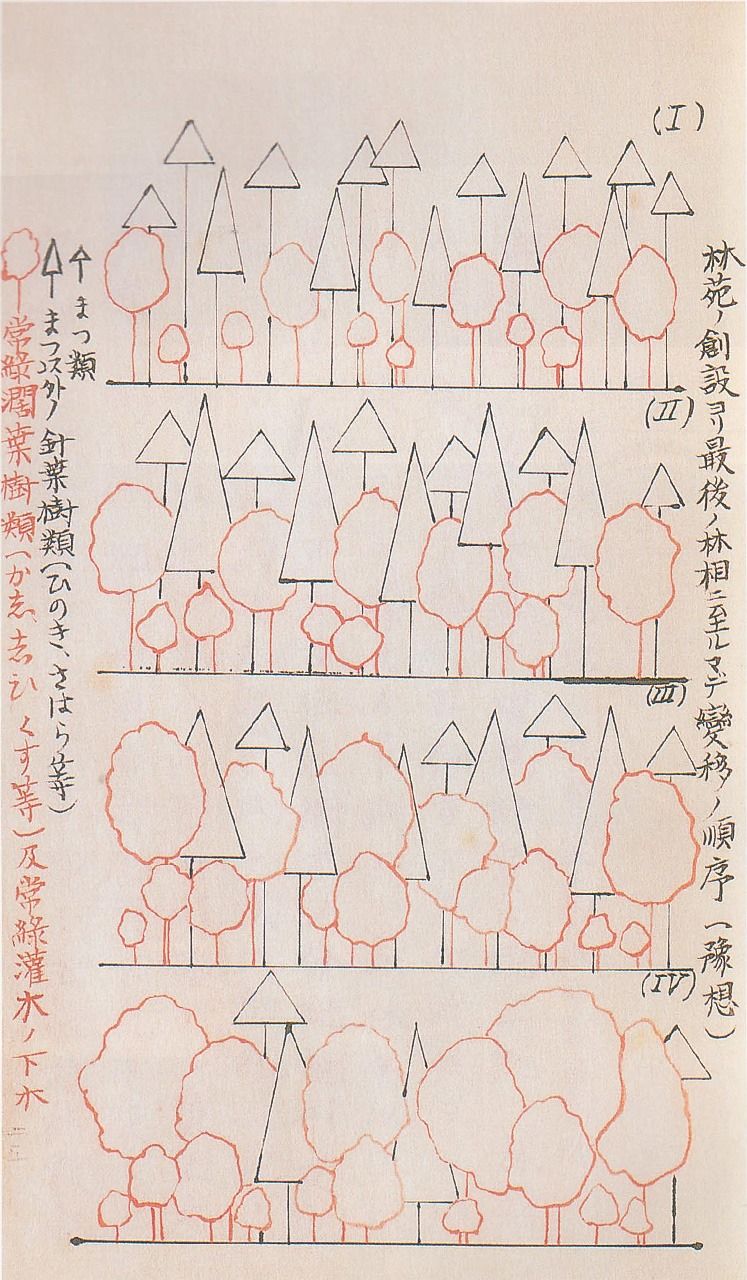

Although the architects of the Meiji Shrine forest did not rely on modern scientific jargon, they had a firm grasp of how materials circle through ecosystems and the role the biological life cycle of insects, birds, and small animals plays in forest development. Using their expertise, they drew up a plan that envisioned four 50-year stages of development, starting from planting and culminating in a mature, self-generating forest dominated by broad-leafed evergreens.

An illustration of the different 50-year stages in Hongō Takanori’s development manual for the Meiji Shrine forest. The project planners anticipated that broad-leaf evergreens like chinquapin, oak, and camphor would gradually replace pines and other conifers.

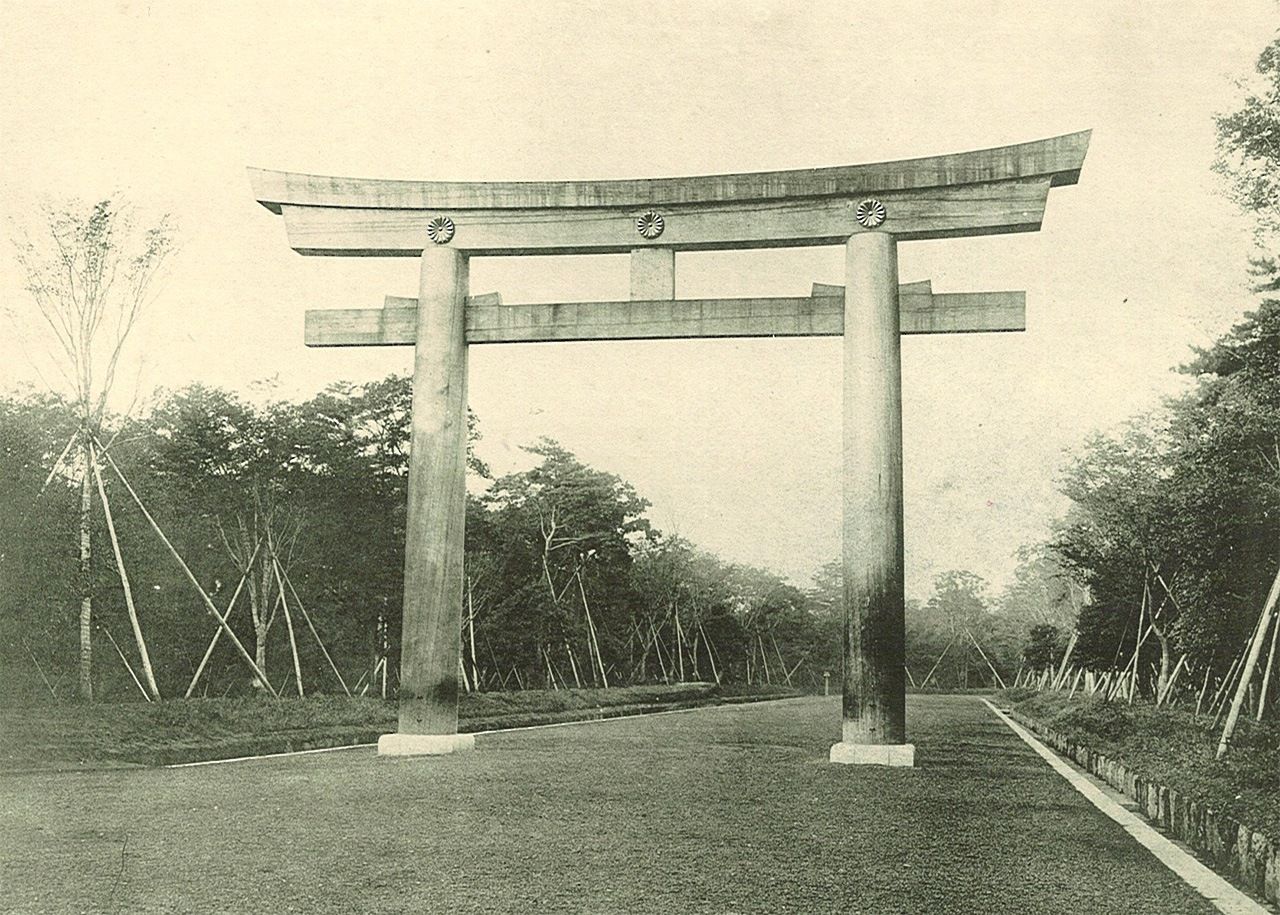

A giant wooden torii towers over the newly planted forest during the construction of Meiji Shrine.

A century later, the same torii is now shrouded by trees.

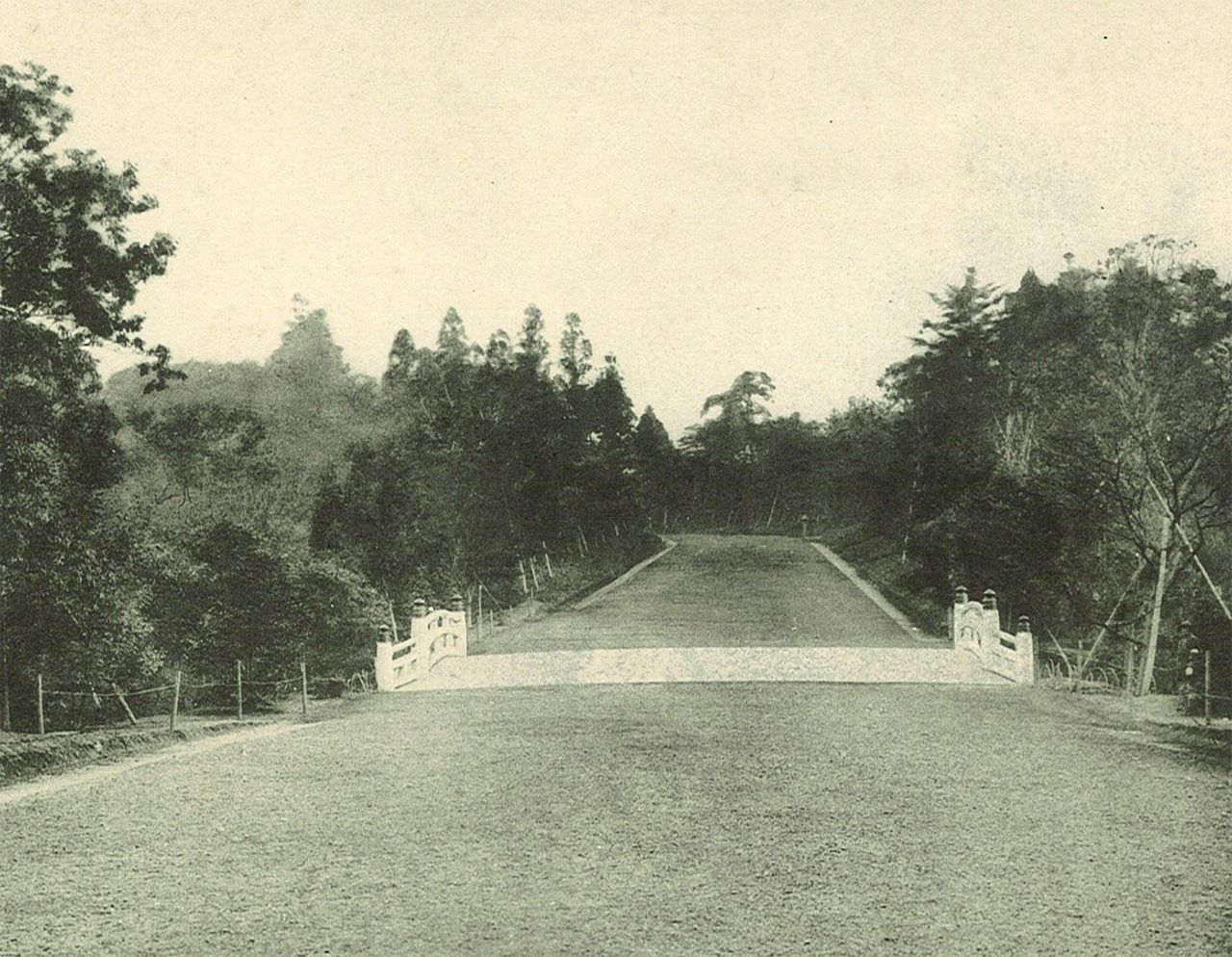

Early on, the paths through the shrine precinct were open to the sky.

Paths today are shaded by overhanging branches.

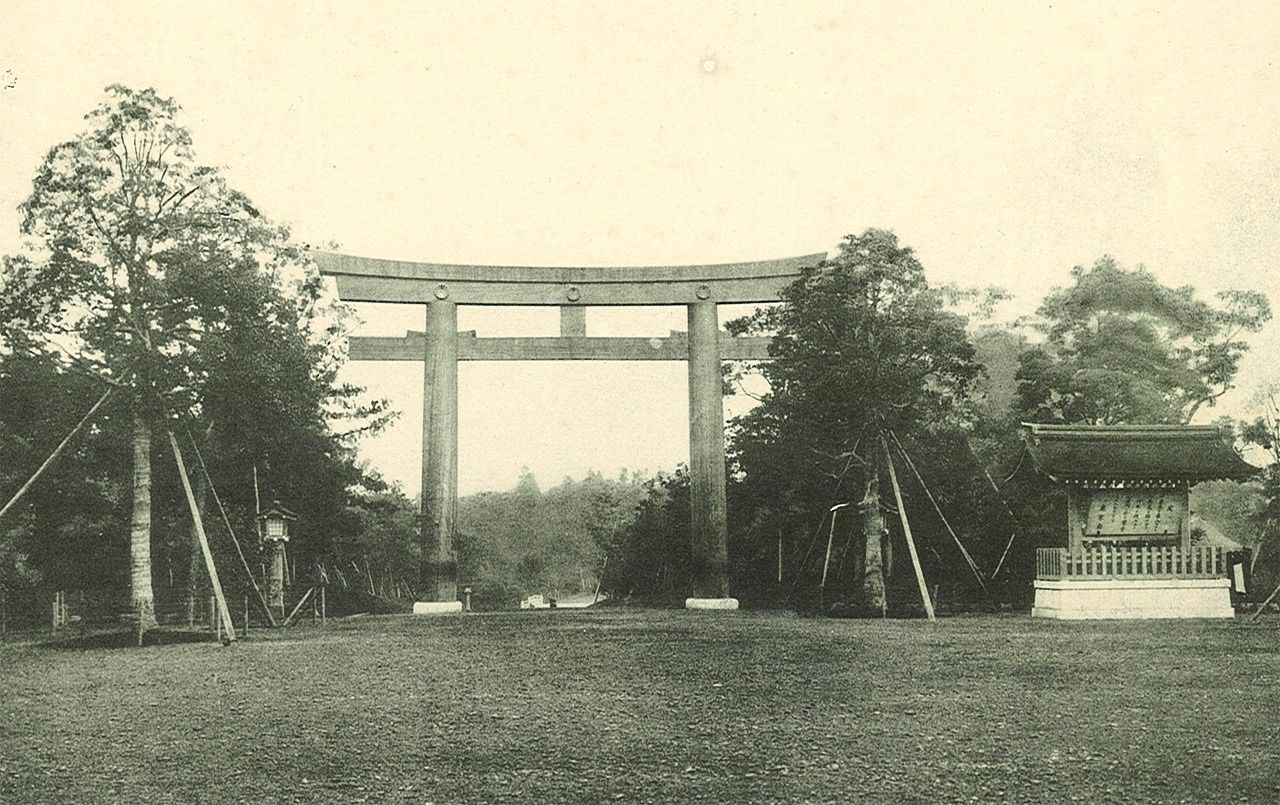

The giant torii at the southern entrance near Omotesandō during shrine construction.

One-hundred years on, the torii is now partially obscured from view.

A Wildlife Sanctuary

In 2010, I had the honor of heading the committee overseeing a comprehensive survey of the Meiji Shrine forest. The purpose of the project was to gauge whether, nearly a century after planting, the environment of the inner garden was developing in the stages envisioned by the planners of the forest. The survey involved some 1,000 plant and wildlife experts and built on the results of an earlier large-scale study conducted in 1980 and intermittent assessments of tree height and girth. Our results, published in 2013, showed unequivocally that the forest had nearly completed its transition to stage two (100 years) and was on course to reach stage three (150 years). The survey also found the confines of the shrine to be a hub of urban plant and wildlife biodiversity, with the various ecosystems supporting a wide range of plant life, lichen, and fungi as well as numerous species of birds, animals, and insects.

Humans, likewise, benefit from the splendid atmosphere of Meiji Shrine, and the site attracts visitors from every corner of the globe. The fact that a man-made forest can not only grow but thrive in the heart of a metropolis of tens of millions of residents is testament to the knowledge and far-reaching vision of the project planners.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: An aerial view of the Meiji Shrine forest. All images courtesy of Meiji Shrine.)