Fukushima Daiichi: Releasing Treated Water a Matter of Personal Concern

Society Environment Economy Health Food and Drink- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Running Out of Space

Climb to the top of the emergency stairs outside one of the buildings in the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, and you see rows upon rows of tanks. The complex, which once supplied electricity to Tokyo, has been transformed into a tank farm.

Tanks for contaminated water stretch as far as the eye can see.

The fuel inside the damaged reactors continues to emit heat and must be cooled continuously. Groundwater and rainwater also seep into the reactor buildings, and all this water is contaminated by radiation.

Adsorption equipment is used to remove most of the cesium and strontium, the main radioactive elements, from the water. The water is then run through ALPS, or Advanced Liquid Processing Systems, to remove most additional radioactive elements, except for tritium, and stored in hundreds of tanks on the grounds. Each steel tank is over 10 meters tall; they stand, in a space-saving honeycomb pattern just 1.5 meters apart. As of October 2020, there were 1,000 such tanks, each holding 1.23 million liters of contaminated water. Standing as high as a three-story building, they are a formidable sight.

Massive tanks, over 10 meters tall, each hold one week’s worth of contaminated water.

Fully 140 tons of contaminated water are produced per day, filling one tank each week. There is enough space right now to store 1.37 million tons of contaminated water, but by summer 2022, all available space will be occupied. Meanwhile, decommissioning work, starting with removing radioactive debris from the reactor cores, is slated to start in 2021. That work requires space for staging areas, laboratories, materials and equipment depots, and other facilities, not to mention access routes for personnel and vehicles.

Officials have known for a while that they would eventually run out of space for storing the tainted water. A Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry study panel examined treated water disposal methods in November 2016. Several, such as evaporating the water into the air, releasing it into the Pacific Ocean, or injecting it into the ground, were compared. Based on technical performance records, in February 2020 the panel recommended evaporating the water or releasing it into the sea. Local agriculture and fisheries businesses, as well as consumer groups, have opposed the plan, but following the panel’s recommendations, the government is planning to release the water into the ocean.

Two Local Characters

Hearing that the treated water would be discharged into the sea reminded me right away of two men I met in March 2014 at a seafood promotional event organized by Fukushima producers for Tokyo-area consumers.

The waters off Fukushima Prefecture are prime fishing grounds, thanks to cold and warm oceanic currents converging there. Local fish, firmed up by swimming against the strong currents, were prized by professional chefs and popular at the Tsukiji, and later Toyosu, wholesale fish market. The Fukushima cooperative, which had suspended its catches immediately after the meltdown, resumed “experimental fishing” in June 2012. But massive efforts, including testing for radioactivity to extra-stringent standards by both the cooperative and the prefecture to ensure that fish from Fukushima is safe, have failed to convince consumers.

At the Tokyo food event, prefectural officials earnestly described the measures taken to assess the safety of seafood from Fukushima and participants, eager to support the prefecture, paid close attention. The subdued mood was suddenly broken up by the arrival onstage of Kikuchi Motofumi, a fisherman from Sōma, a coastal town not far from Fukushima Daiichi, and Iizuka Tetsuo, an intermediate fish wholesaler.

The pair, looking like overgrown rambunctious schoolboys, hardly fit the image of people impacted by the disaster. They entertained the audience like a pair of veteran stand-up comedians, talking about their childhoods growing up in a fishing town and their days working as cooks aboard fishing trawlers, when they had to prepare four meals a day for the hungry crew. Next, they expertly filleted whitespotted greenling to make into dumplings for fish broth for the audience. The dumplings were soft and plump and the broth was rich and tasty. As Kikuchi and Iizuka made their rounds of the tables, proudly urging the audience to admit how tasty the food was, people’s attitudes changed: They were not just looking for ways to support areas impacted by the disaster, they were becoming avid fans of Sōma and its fisheries products.

Ironically, though, the greenling was sourced from Hokkaidō rather than Fukushima. Due to concerns about excessive radiation levels, greenling is not on the list of species targeted for experimental fishing. At the end of the day’s event, Kikuchi delivered an unforgettable speech about his desire to keep fishing off of Sōma and his hopes that attendees would one day visit Fukushima to eat dumplings made from fresh-caught fish.

In autumn 2015, Kikuchi, Iizuka, and local colleagues started a quarterly newssheet called Sōma taberu tsūshin (Sōma Dining News). Each issue features a local farmer or fisherman, mainly from Sōma but also from other towns along the coast, spotlighting the attractions of their products.

Members of the newsletter’s editorial department. They have different day jobs, but they all love Sōma. (Courtesy of Sōma taberu tsūshin)

I have been a Sōma taberu tsūshin subscriber for a while now myself, and I have visited Sōma several times on tours organized by the paper. My repeat visits opened my eyes to the fact that the local farmers, fishermen, and seafood processors take great pains to ensure that their products are well within designated radiation levels. They work hard to dispel lingering doubts about the safety of food from Fukushima; indeed, I believe that multiple safety checks may in fact make Fukushima products safer than those from elsewhere in the country.

Kikuchi and Iizuka are not alone. Many Fukushima food-related businesses, devastated by the meltdown, have been painstakingly rebuilding connections with consumers, one step at a time, over the past 10 years. Discharging treated water into the ocean would be downright cruel if it meant they had to start all over again.

The Treated Water

When I visited Fukushima Daiichi in September, the plant gave us a tour of the ALPS water decontamination facility. Radiation levels in 96% of the compound are low enough not to require wearing protective gear, but here everyone donned overalls and a full-face mask to enter the facility.

Dressed in protective garb to tour the inside of the ALPS facility.

TEPCO treats the water first by adding a solution to precipitate cobalt, manganese, and other substances, and then running it through seven multinuclide removal systems consisting of 18 towers using activated charcoal and ion exchangers. Although ALPS cannot completely remove all radioactive substances, the water is compliant with government standards for releasing radioactive materials from nuclear plants into the environment. For example, ALPS can reduce strontium concentration to one-billionth of its previous level.

ALPS can remove 62 types of radioactive substances from contaminated water. Workers on site wear full protective gear.

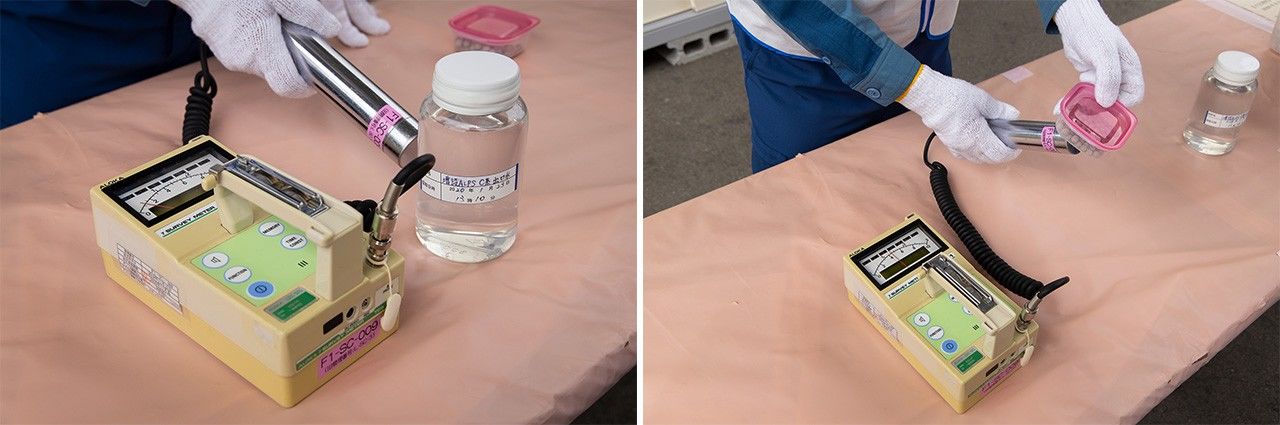

In the photos below, the dosimeter measuring radioactivity of the treated water sample in the jar in the photo on the left registers a 1. In the photo on the right, the tap water sample (in the plastic container), containing a popular bath additive from a “radium ball” that gives a hot-spring-like effect, registers a 3 on the dosimeter. Maybe we cannot say that the treated water is completely safe, but it does not seem hazardous compared to a product like the “radium ball,” available online and handled by delivery services as an ordinary parcel.

At left, water treated by ALPS, with the dosimeter registering a 1; at right, water with a “radium ball” additive produces a dosimeter reading of 3.

Improving Literacy

It is not possible to remove tritium from the contaminated reactor water with current technology, but the substance is present in nature and in vapor, rainwater, and tap water. It is only weakly radioactive, so it cannot penetrate the skin and irradiate the human body. Even if ingested, it will be excreted just like water and does not accumulate in body tissues.

If the treated water is released into the ocean, the government says it plans to dilute it to a one-fortieth solution with sea water and release it in small amounts over a period of 30 years. This one-fortieth level of concentration is far lower than the World Health Organization standard for tritium levels in drinking water.

Some say they cannot trust any explanation given by TEPCO, which caused the accident, or that TEPCO is hoodwinking the media too. I asked Professor Yasuda Hiroshi of the Hiroshima University Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine about the effects of releasing tritium into the sea. “Tritium, which is produced by cosmic rays, is an isotope present in nature. It’s also been widely dispersed throughout the environment following atomic bomb testing after World War II and through nuclear power plant operation and other sources. However, it has not been demonstrated to be harmful to human health,” he says.

“Most tritium is present in the form of HTO, where one of the hydrogen atoms in H2O has been replaced by a tritium atom. Since HTO behaves almost exactly like water, if released into the sea it will disperse quickly and won’t accumulate in seafood, so the amount of tritium ingested by humans via this route is almost negligible compared to all the radioactive isotopes we are exposed to in the natural world. Furthermore, the radiation emitted by tritium, in the form of beta rays, is weak and is soon excreted through our sweat and urine. Tritium doesn’t stay in the body for very long and, compared to other radioactive isotopes, any possible health effects are quite small.”

Yasuda continues, however: “No matter the type or concentration of isotope, the social and psychological aspects of artificially releasing a radioactive substance into nature need to be taken into consideration. In this case, releasing treated water could really affect the livelihoods of local residents who work in fishing, so any such action should be carefully explained and measures taken to offset harmful rumors.”

That is the problem with releasing treated water into the ocean. Kikuchi, the Sōma fisherman, says, “The government and the scientific experts should have tried harder to explain things to the public even before getting into the issue of whether to release the water. Fukushima would not be the first case; nuclear plants all around the world are already releasing treated water. Consumers should access publicly available information, see with their own eyes, and decide for themselves, rather than let themselves be swayed by impressions without knowing the facts.”

Electricity produced by Fukushima Daiichi, which sits more than 200 kilometers north-northeast of Tokyo, was sent to the country’s capital to meet the energy needs of a megacity. It was not consumed locally, and yet the prefecture’s residents, who obtained electricity from elsewhere, have been the most severely affected by the accident. The treated water may ultimately be released into the sea far from Tokyo, but metropolitan residents like me who consumed electricity from Fukushima Daiichi need to pay more attention to this issue.

We need to stop and think a bit, rather than irresponsibly spreading rumors or refusing to buy Fukushima products because we feel they may somehow be tainted. Showing proper respect for the risks, we should make rational decisions after doing our best to learn the facts.

Iizuka and Kikuchi urge us, as food consumers and electricity users, to give more attention to the issue. Iizuka states: “My frank impression is that the government has already decided to release the treated water. Three out of ten people say they avoid Fukushima products. They won’t listen, no matter what I say, but I’ve done my best to approach the remaining seven. Even if a few more individuals decide that they don’t want to ‘buy Fukushima’ because of the water release, I’ll keep on trying to raise awareness.”

Intermediate seafood wholesaler Iizuka Tetsuo. (Courtesy of Sōma taberu tsūshin)

Kikuchi adds: “We’ve been battling the stigma associated with the plant ever since the March 11 disasters, so I don’t think the water release will make much difference. I’d like to start something so new that it will blow all the rumors away, and do something really cool with the folks around here. I may not be able to move the world, but I’d like to move my children’s hearts.”

Fisherman Kikuchi Motofumi. (Courtesy of Sōma taberu tsūshin)

Information about water treatment and the roadmap to decommissioning Fukushima Daiichi is available on the TEPCO and METI websites. With data and graphics, the information is clear and accessible even without a specialist background. Fukushima Prefecture also releases data on monitoring in various parts of the prefecture, to protect residents’ health and safety.

- TEPCO: Treated Water Portal Site https://www4.tepco.co.jp/en/decommission/progress/watertreatment/index-e.html

- METI: Mid-and-Long-Term Roadmap Toward the Decommissioning of TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station Units 1–4 https://www.meti.go.jp/english/earthquake/nuclear/decommissioning/index.html

- Fukushima Prefecture: Fukushima Revitalization Station https://www.pref.fukushima.lg.jp/site/portal-english/

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Tanks for storing treated water at Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station. Beyond the tanks are reactor units 1–4. Banner photo and on-site photos by Hashino Yukinori of Nippon.com.)

Fukushima TEPCO Great East Japan Earthquake nuclear power Fukushima Daiichi 3/11