The Clever “Karasu”: Wise Old Birds Living Side by Side with Humans

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Reputation Flutters to Earth

Before we begin, we have to make one thing clear. There is actually no species of bird called the karasu, commonly translated as “crow.” Karasu in Japanese is actually a collective word applied to five closely related yet different species classified under the genus Corvus, belonging to the Corvidae family in the order Passeriformes.

Karasu make frequent appearances in the media in Japan. Yes, other wild birds like the toki (crested ibis) or the kōnotori (white stork) show up in the news as well, most often in stories talking about their endangered or nearly extinct status. Yet the birds that appear most frequently in the news are the karasu, and the tone is very different from how the media cover other birds. Mostly they are stories of friction between karasu and humans in our daily lives—articles painting karasu as pests that foul neighborhoods with raw trash pried from garbage bags, or reports about the earsplitting racket (not to mention piles of droppings) when of karasu gather together.

Around the world, though, tradition presents another image of karasu entirely. Since ancient times, corvids have been depicted in every corner of the world as messengers of the gods or purveyors of knowledge. Take the ravens Muninn and Huginn, the symbols of thought and reason, who in Norse mythology were said to have served the great god Odin. In Japan as well, there is the famous yatagarasu, the raven deified at the three Kumano Sanzan shrines along the Kumano Kodō pilgrimage route in Wakayama. It is recorded in the Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan), Japan’s oldest historical text, that Yatagarasu guided Japan’s legendary first emperor Jinmu. In ancient Chinese legends, a three-legged yatagarasu was said to live in the sun as a bird of good fortune and tidings. In much more recent times, this three-legged bird has won new fame as the emblem of the Japan Football Association.

A banner bearing a yatagarasu image at Kumano Nachi Daisha, one of the Kumano Sanzan shrines.

Ascroll depicts the three-legged yatagarasu inside the Kumano Nachi Daisha shrine.

Many Shintō shrines across Japan hold an obisha matsuri around the New Year of the traditional lunar calendar. During this festival, supplicants pray to an archery target that bears the image of a karasu, asking for safety and health for them and their families. In this way, karasu have lived on across the centuries in Japanese culture. Yet today, their real-world brethren no longer enjoy the high status of the past.

A priest prays before a target decorated with karasu.

Our Neighbors from the Sky

There are five species in the family Corvidae that can be spotted in Japan: the hashiboso garasu, the hashibuto garasu, the miyama garasu, the kokumaru garasu, and the watari garasu. Of these, the two that live here all year around are the hashiboso garasu (carrion crow) and the hashibuto garasu (jungle crow).

A hashiboso garasu, or carrion crow. Smaller than the hashibuto garasu, it has a short, narrow beak and a croaking call.

A hashibuto garasu jungle crow. It has a thick beak and vocalizes with a sharp, clear “Kaw!”

Japanese usually refer to both jungle crows and carrion crows simply as karasu. However, they are not the only members of their grouping to be found in Japan. During the winter months miyama garasu (rooks), kokumaru garasu (jackdaws), and watari garasu (northern ravens) migrate to Japan from the continent. So far watari garasu have only been sighted in Hokkaidō, but the more recent arrival of miyama garasu as well is a particularly intriguing development.

A miyama garasu. These rooks are distinctive for their light grey beaks with a whitish base. They migrate to Japan in the winter.

As late as the 1970s, the migratory miyama garasu rook had only been observed in Kyūshū. By the 1980s, however, they had started appearing in western Japan as well, then in Niigata and Akita Prefectures and other spots along the Japan Sea coast, and eventually spread throughout the country. This may not be quite equivalent to the shifting distribution of fish species that has been observed as a consequence of global warming, but it is nonetheless becoming necessary to redraw the distribution map of corvids in Japan.

Indeed, migratory corvids are also becoming more pervasive even in Hokkaidō. While there is no statistical data to support this, I have heard anecdotally that the increase has paralleled the growing popularity of hunting ezoshika deer in Hokkaidō, a trend that has resulted in increasing numbers of deer carcasses being left behind by hunters, a perfect magnet for ravens and crows.

Humans and Karasu: The Big-brained Omnivores

For humans, these birds are not so much creatures of the forest as a part of our lives from ages past. One piece of evidence is how frequently they appear in the annals of the human race—in the Old Testament of the Bible, the Quran, and other ancient works. It may well be the reason that karasu are celebrated in so many Japanese rites as well.

One thing that is clear, however, is that karasu themselves have discovered advantages to living near humans. In recent years in Japan, creatures including boars and bears have been emerging from the wild to feast on people’s agricultural produce and garbage, but karasu were much quicker to discover how convenient living near us can be. One biological reason for this is their omnivorous diet, but the other is their highly developed brains. In short, karasu can eat most anything, from crops to thrown out leftovers. And they also have the intellect to analyze the connection between human behavior and food. Some have even figured out that after funerals in Japan, food will be put out on the altar as an offering—a tasty treat indeed.

In this way, karasu are our “birds next door,” sharing the cycle of our daily lives in much the same way as our human neighbors. Yet be they humans or birds, the undeniable truth is that we do not always find ourselves loving our neighbors. Let me introduce some specific examples of the many frictions between karasu and humans in Japan today.

Damage Too Vast to Ignore

Karasu cause problems in every setting imaginable. After all, wherever you find people, you also find karasu. I have listed some of the worst crime scenes below.

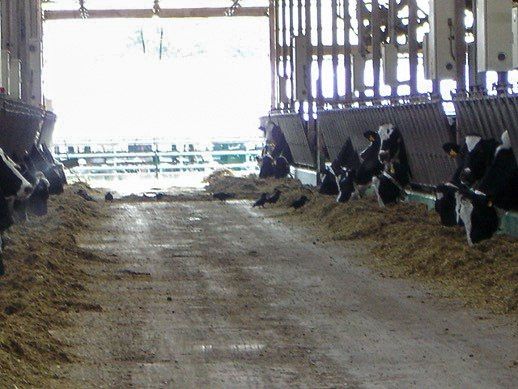

Livestock barns: Hashibuto garasu jungle crows love barns and stables. Corn kernels and wheat in leftover feed are treasured delicacies, while the nearby manure piles are a cornucopia of goodies, packed with tasty worms and insects. That would be fine if all the karasu were doing was eating the trash. However, it turns out that a cow’s udder is at almost the same height as a carrion crow’s head. Crows have been known to jab cow udders with their beaks, leaving cuts and scratches that can get infected, leading to mastitis. In some cases, the cows can no longer produce milk and have to be put down. Karasu can peck at the wounded areas so hard that the blood vessels burst and the cow literally bleeds to death. These avian visitors are further believed to spread diseases to livestock, and farmers try to keep them as far from their livestock as possible.

Birds stealing food from a cowshed.

Zoos: Hashibuto garasu jungle crows are as fond of zoos as they are of cattle pens. Since many zoos keep a wide variety of animals, from carnivores to herbivores, there is always an abundant variety of fodder, making zoos a perfect feeding ground. This is an example of what naturalists call “listeriosis,” where smaller creatures share nests with other animals and eat their food. There have also been incidents where the crows have pecked younglings in zoos hard enough to injure them, making them even more despised by zookeepers.

Electric power companies: While it is not widely known, the damage caused by karasu to utility firms is also substantial. There have been many cases where nests built on power line poles and transmission towers have disrupted power transmission. In some instances, materials karasu have gathered to build their nests have shorted out power line connectors, causing blackouts that affected tens of thousands of households. The Hokuriku Electric Power Company patrols its tens of thousands of power line poles every year, taking down any nests that could cause a blackout. In 2018, the company removed no less than 15,880 nests from February through May, the prime nest-building season. These problems affect every electric power company in the country, and the annual cost of patrols, nest removal, and installing guards and other barriers to prevent nest building is said to run to hundreds of millions of yen each year.

A nest on an electric power pole.

Urban areas: Karasu do more than rummage through raw waste and scatter trash around garbage collection sites. Residents also complain about the birds’ racket, and there are even cases of karasu attacking passing pedestrians, especially when they are raising their hatchlings in the spring. From autumn through the winter months, meanwhile, flocks of karasu may descend on urban telephone lines and tree-lined streets, driving local residents crazy with both their racket and their droppings. Flocks as many as 10,000 strong have been known to line up along power lines in urban areas, leaving so many droppings on the street below that it creates serious sanitation concerns. In just the last few years, large numbers of miyama garasu rooks have begun migrating from the continent to urban areas in Kyūshū, causing similar problems there.

A garbage collection site looted by karasu. Residents often cover trash with netting, but the wily birds can drag the bags out and rip them apart in their search for food.

Karasu perched on urban power lines. Streets below end up fouled with droppings.

Crows occupy a roadside tree, both their racket and defecation causing problems for residents.

Damage Caused by Karasu

| Location | Damage | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Livestock sheds | Attacks on livestock, pecking milk cows’ udders (causing mastitis), introducing diseases |

| 2 | Railways | Leaving debris on tracks, building nests on catenary lines |

| 3 | Buildings | Damaging outdoor ducting and insulation on rooftop air-conditioning units, eating and fouling rooftop greenery |

| 4 | Fields and rice paddies | Crop damage |

| 5 | Electric power companies | Electrical substation and powerline troubles, nests on transmission towers, damage to insulators and cable cladding, bird droppings, noise pollution |

| 6 | Residential areas | Scattering garbage, attacking pedestrians, roosting in roadside trees, bird droppings, noise pollution |

| 7 | Shipping companies | Damaging cardboard boxes in warehouses, damage from droppings |

| 8 | Zoos | Stealing animal food, harming young animals, building nests |

| 9 | Golf courses | Tearing up the turf, flying off with golf balls |

| 10 | Solar panels | Dropping debris and damaging solar panels |

| 11 | Schools | Attacks on schoolchildren (especially when building nests and raising hatchlings) |

| 12 | Carports | Damaging car gaskets and window wiper rubber blades, fouling with droppings |

Smart Enough to Be Dangerous

All these aspects of karasu crows and ravens have earned them the nickname “the feathered primates.” It is exactly because they are so intelligent that they can behave in ways we would never have dreamed of. Meanwhile, their diversity and flexibility enable them to adapt to our own complicated lifestyles, so much so that even when we find ways to counter one set of problematic behaviors, they will likely bounce back in ways that are even harder to counter than before.

Hashibuto karasu jungle crows like meat even more than their hashiboso carrion crow brethren do. With the discarded food available in cities, the buildings and other constructions that take the place of trees, and the absence of any raptors, their natural enemies, urban jungle crow numbers have soared.

Compared to other birds karasu have very highly developed brains. Their ratio of brain mass to body weight is 1.4%, ten times greater than the 0.12% ratio of chickens. This places them vastly closer to humans (1.8%) than to their poultry relatives. Their ability to predict where cars will pass and place nuts there so the tires will crack the shells open, and to reposition the nuts if their first estimate was incorrect, is just one manifestation of this. It is no doubt because of this intelligence that they knew from ages past that they would never want for food or shelter so long as they lived nearby us. Even as our own lifestyles have been transformed, they have been able to adapt and keep pace. The more our production efficiency rises, the more surpluses we create, the more food and housing materials are left over for them, and the more their numbers increase.

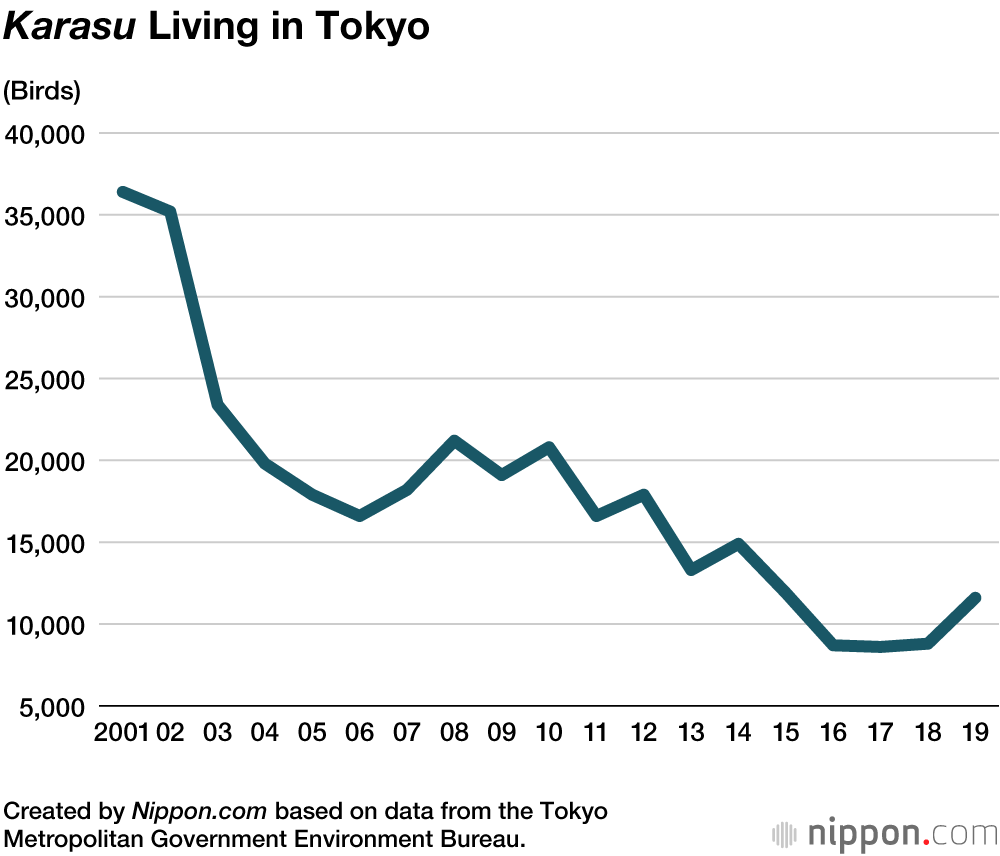

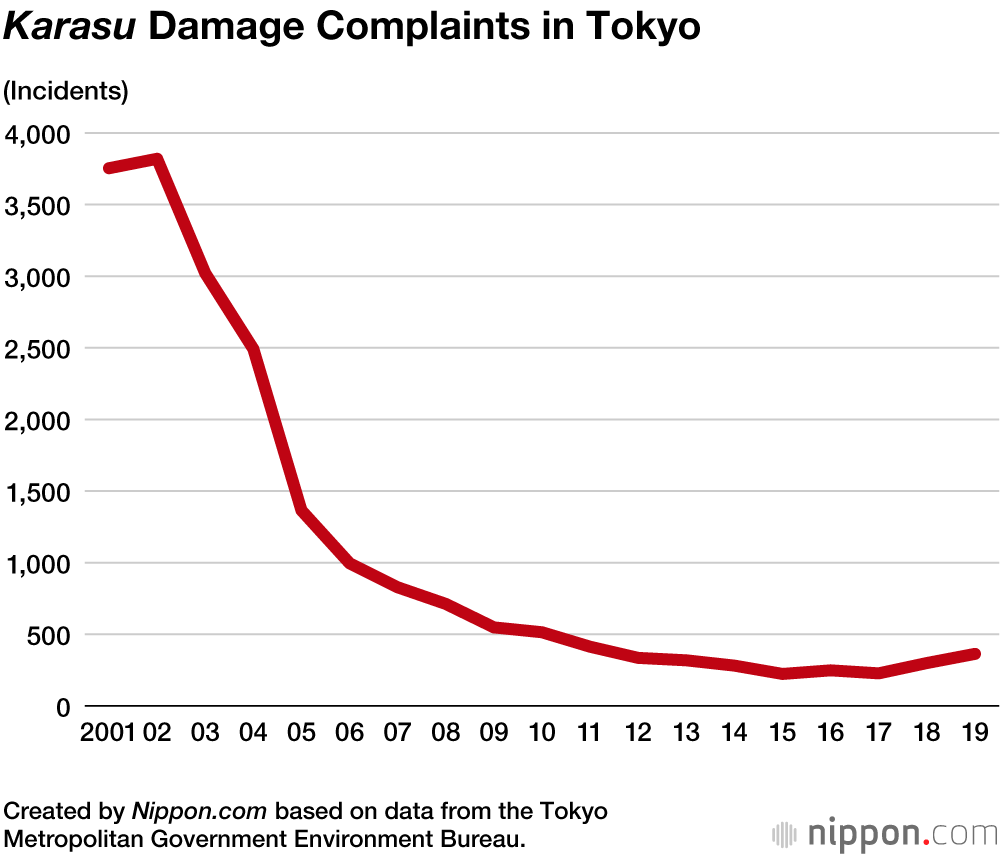

At the time of Japan’s high-growth period up through the early 1970s, it is estimated that approximately 37,000 karasu lived in metropolitan Tokyo, flocking around the garbage mixed with drifts of leftover food dumped in the back alleys of the city’s downtown districts. The crow problem peaked around the turn of the century, and various countermeasures were put in place, including moving garbage collection times to the middle of the night before the karasu were active, making the people generating garbage take responsibility for separating it out into different categories themselves, and more. These measures have proved effective, and today the number of karasu living in downtown urban districts has fallen to a third of what it was before. The number of public complaints is only a tenth of what it was at the time, and crow-human relations have improved somewhat. However, it took 20 long years of effort to bring us to where we are today.

Once the delicate balance between human beings and wild animals has been lost, it is no easy task to reestablish a way for us all to coexist together. All creatures living in the wild must constantly hunt for food to eat, and once they find a reliable source they are unlikely to abandon it. I believe it is the duty of we humans, always so prone to disrupt the natural balance, to decipher the behavior patterns and habits of these intelligent birds, and seek out a wiser way for us all to live together.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A hashibuto garasu jungle crow. All photos by the author.)