Cambodia’s Digital Currency Signals Future of Finance

World Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

INTERVIEWER The way that Soramitsu, a mere start-up, used its ideas to create a digital currency for an entire country’s central bank was reminiscent of the style of Steve Jobs and Bill Gates in the early days of Silicon Valley. What made you turn your attention to digital currency?

MIYAZAWA KAZUMASA I’m nowhere near in the same category as Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, but I did work at Sony for a long time. At Sony, there’s a culture of always trying to be the first to do something, and I myself wanted to do something that no one had done before. While stationed in Silicon Valley, I was responsible for developing the first ever Vaio computer, although Sony lost a lot of money on that project. Deciding that the future was going to be about services and the Internet as opposed to hardware, I returned to Japan and launched the Edy e-money platform.

The name “Edy” is made from the first letters of euro, dollar, and yen. I wanted this to be a global payment system. However, technological and other barriers meant that Edy did not take off at all overseas, and only gained popularity in Japan. Bitcoin, on the other hand, was a runaway global success. It was my frustration at losing out to Bitcoin that made me join Soramitsu, where I am now CEO. Our company that uses blockchain technology, in which a distributed network of computers is combined with encryption technology to synchronize and store transaction data.

INTERVIEWER Are you saying that the process of focusing on what you really wanted to do lead you to create a digital currency?

MIYAZAWA Digital currency development really has become my life’s work. I felt the time was finally right. And then, as the technology was finally catching up with my ambitions, I happened to make the acquaintance of officials in Cambodia’s central bank, which made me realize that this was what I was destined to do.

INTERVIEWER If blockchain tech had been around when you were developing Edy, would Edy have been a digital currency too?

MIYAZAWA I believe it would have. I remember when we started working on Edy, one university researcher was furious about our approach. He said we were using the technology wrong because our system did not allow value to be transferred between individual users. From an academic point of view, the platform did not make sense in terms of economic theory. Rather than being a true digital currency, Edy was something more like a prepaid smartcard.

In those days, however, we did not have any means of enabling secure transferability, and were therefore forced to pursue a nontransferable, account-based approach. This approach, in which funds are transferred between the parties’ accounts, was copied by Suica and later by PayPay and Line Pay. I am therefore partly responsible for the fact that the Japanese finance industry is characterized by inefficient payment protocols that don’t allow value to be transferred directly between individuals, because I ignored opposition from academics. I therefore feel we must change that—in other words, reform society.

An Offer Too Good to Be True

INTERVIEWER When Cambodia’s central bank, the National Bank of Cambodia, went to vendors and asked them to create a digital currency, you were able to put up your hand first because you were a start-up, is that correct?

MIYAZAWA Someone claiming to be from the central bank messaged us on social media, saying they wanted to trial our technology. I initially assumed the message was a fake, because I thought there was no way a central bank would just contact a start-up like that. I felt it had to be a scam. After corresponding with the person for some time, however, I realized they had to be genuine. And so, I travelled to Cambodia with the founder of my company, and indeed our contact turned out to be the National Bank of Cambodia.

I saw many technologies come and go during my time at Sony. Sony used to have a video format called Betamax which lost out to VHS, Our MemoryStick format lost out to the SD card, too. This experience brought home to me that there was no point creating technology for the Japanese market. We would never beat the competition as long we remained isolated. On several occasions, I have taken on the world and learned the hard way that you need aim to be the global standard in order to survive.

Soramitsu founder Takemiya Makoto was born in the United States, but after moving to Japan fell in love with the country and became a citizen. Takemiya too wanted to vie for the global market from the start, and as soon as we had a prototype, he went to New York to pitch our product, and even attended the Davos conference in Switzerland. He felt that without doing this there was no way that we would survive. I believe that’s what caught the attention of the Cambodian central bank.

The offices of the National Bank of Cambodia in Phnom Penh.

Soramitsu founder Takemiya Makoto (second from right) and Miyazawa (third from right) at Angkor Wat.

INTERVIEWER Your business was always very global, something made possible by Soramitsu’s technical expertise.

MIYAZAWA That’s right. Takemiya really is a genius. After finishing university, he joined the US Army, where he researched neuroscience and artificial intelligence. It was when he was working at NTT’s Science and Core Technology Laboratory in Nara that Bitcoin was released. Takemiya says while he realized Bitcoin was a fantastic achievement, he believed he could create something better, and went onto do just that. He created our cutting-edge technology like Steve Wozniak did at Apple. I’m perhaps more of a Steve Jobs type. I can write code, but not being overly proficient at it, in the process of coding, I learned about new technologies and ended up focusing on how we could make them catch on.

INTERVIEWER Soramitsu’s business model was to release its independently developed blockchain technology, Hyperledger Iroha, as open-source code and make profit on the margins. That’s different from the approach traditionally taken by Japanese businesses.

MIYAZAWA Some other Japanese companies have developed blockchain protocols, but we’re the only outfit competing in the global marketplace with an open-source offering. The major corporations that have developed these protocols confine themselves to the Japanese market. What’s more, rather than using an open-source model, they operate on a business model of earning income from licenses. That’s why their formats do not take off. It’s a real pity that they are so closed.

Japan’s Finance Sector Falling Behind

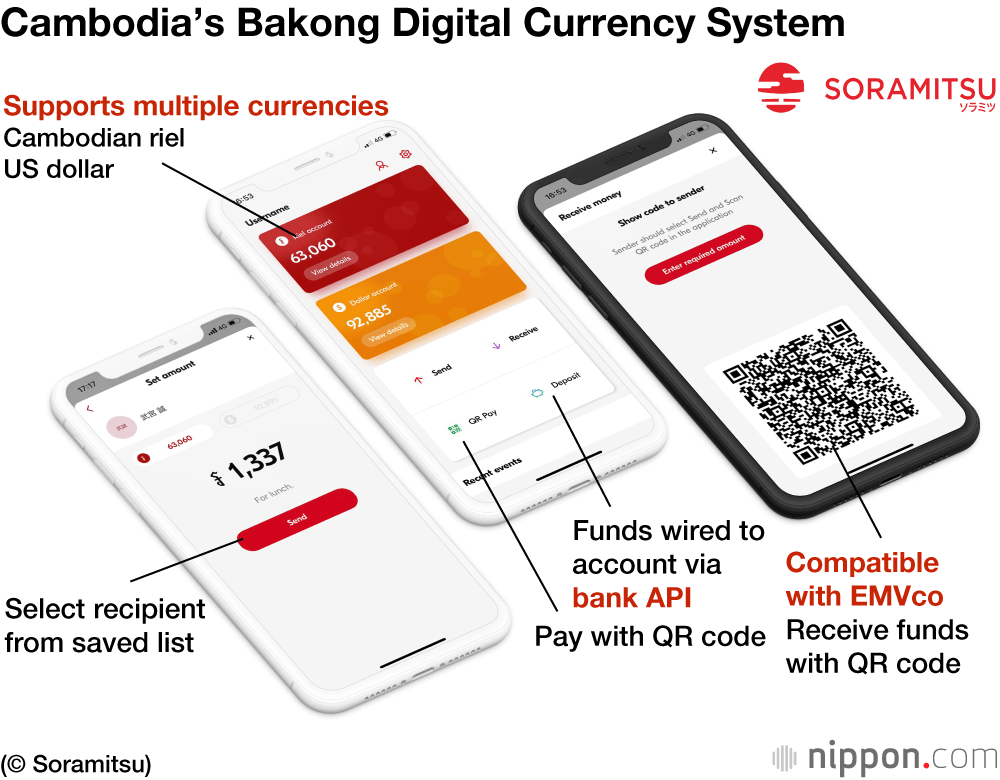

INTERVIEWER Let us return to the subject of the Bakong. Cambodia’s central bank was troubled by the fact that the country had more US dollars than riel in circulation. However, after Bakong was launched, the riel overtook the dollar as the preferred currency.

MIYAZAWA The National Bank of Cambodia is a tightly run ship. It has a young and studious staff, who, despite being from finance backgrounds, are also tech savvy—and, in a way, not tied down. In contrast, those working in Japan’s finance sector are wedded to convention, and many executives either believe it’s not possible to modify their existing systems, or simply don’t want to make a mistake.

If Japanese finance maintains its current path, Japan will fall farther and farther behind the rest of the world. Heavyweights in the Japanese financial world say what we did was only possible in Cambodia because the country lacks infrastructure. The Cambodians are also forward-looking and have the pluck to aim high. The reason that we were able to launch our currency so quickly was that the bank already had a concept. It already knew exactly what it wanted its CBDC—its central bank digital currency—to be.

Japan’s finance industry has no concept of what its digital currency should be. It is not clear what kind of central bank digital currency Japan should have. We are still at the stage of planning gradual rollouts of trials. The Cambodians, on the other hand, had a very clear idea of what they wanted. When we ran risk simulations and simulated impacts on the bank, they understood everything. That was in 2016. Cambodia five years ago had a much clearer idea of what it wanted—to reduce dollar usage, to boost use of the riel—than Japan of today.

National Bank of Cambodia Director General Chea Serey speaks at the Bakong launch ceremony on October 28, 2020. (© Kyōdō)

The Threat of the E-Yuan

INTERVIEWER Are the Cambodian authorities worried about China’s digital yuan?

MIYAZAWA I think they are. People are concerned about the rise of the e-yuan. While the Chinese state that the currency will only be used domestically, I think they are just saying that to be expedient. China is holding sessions with countries like the UAE and Thailand to explore the possibility of using the e-yuan overseas. They are also talking about an e-yuan international alliance of sorts that will deploy the currency throughout the Belt and Road, and throughout Asia. If the e-yuan spreads, the United States will no longer be so able to use the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications, or SWIFT, to impose economic sanctions, and China will be able to use the e-yuan to send funds freely to the likes of North Korea and Myanmar, irrespective of sanctions.

A sign advertising the Bakong platform in Phnom Penh. (© Soramitsu)

INTERVIEWER How do you think the rise in popularity of China’s and other digital currencies will affect society globally?

MIYAZAWA I can conceive of three scenarios. One is that Japan’s financial institutions successfully follow the right path and take on board new digital technologies.

The second is that this doesn’t happen, and that existing financial institutions are replaced by new platforms. These might take the form of platforms like Rakuten Pay or Line Pay, or even Facebook. Giant platform providers use new technologies to provide convenient services, which consumers opt for over traditional platforms, causing Japan’s financial institutions to lose even more market share and the less successful banks to be culled. That is the second scenario.

The third scenario is that rather than everything being controlled by a centralized platform, we see the emergence of decentralized finance, in which assets are held in a decentralized manner and distributed democratically. Banks may become a thing of the past. For example, in what’s known as a decentralized exchange, or DEX, assets are exchanged automatically without human intervention. These exchanges are able to swap currencies and whatever else. Lower costs will see these kinds of platforms become more prominent. I believe these three dynamics will coexist while growing the market.

INTERVIEWER You are on the Bank of Japan’s digital currency roundtable committee. What direction do you think digital currency should take in Japan?

MIYAZAWA I believe the second scenario I described would not be good. If platform providers gain control of Japan’s financial sector, banks will have their credit creation function limited, thereby preventing them from stimulating the economy. I therefore believe the first scenario is the most desirable. Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, which are a key part of my third scenario, will continue to grow, but I think the majority of Japanese consumers will prefer to keep using banks if their services are more convenient. Personally, I am rooting for the first scenario.

The Bank of Japan is assuming that third-party digital currencies will coexist with, and link to, its planned CBDC issue. For this to happen, however, the BOJ needs to make Japanese deposit accounts easier to use. In the interest of deposit liquidity, I believe that banks need to issue their own digital currencies using blockchain or a comparable technology, thereby reducing fund-transfer costs by at least an order of magnitude. They need to build systems that support instant payments and transferability of value, making use of smart contracts to allow the stipulation of various rules governing payment methods. If this does not happen, consumers will drift to more convenient payment methods that incorporate new technology.

A company by the name of Digital Platformer, established in April 2020, provides platforms that enable banks and local bodies to issue nationally recognized digital currencies. This company uses the same technology as Cambodia’s Bakong platform, and in the future I believe it will also integrate with the BOJ CBDC to provide a next-generation payment system that joins the nation’s banks to local bodies, thereby offering consumers a low-cost, highly convenient digital currency.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A display explaining the Bakong, Cambodia’s digital currency system, in Phnom Penh. © Kyōdō.)