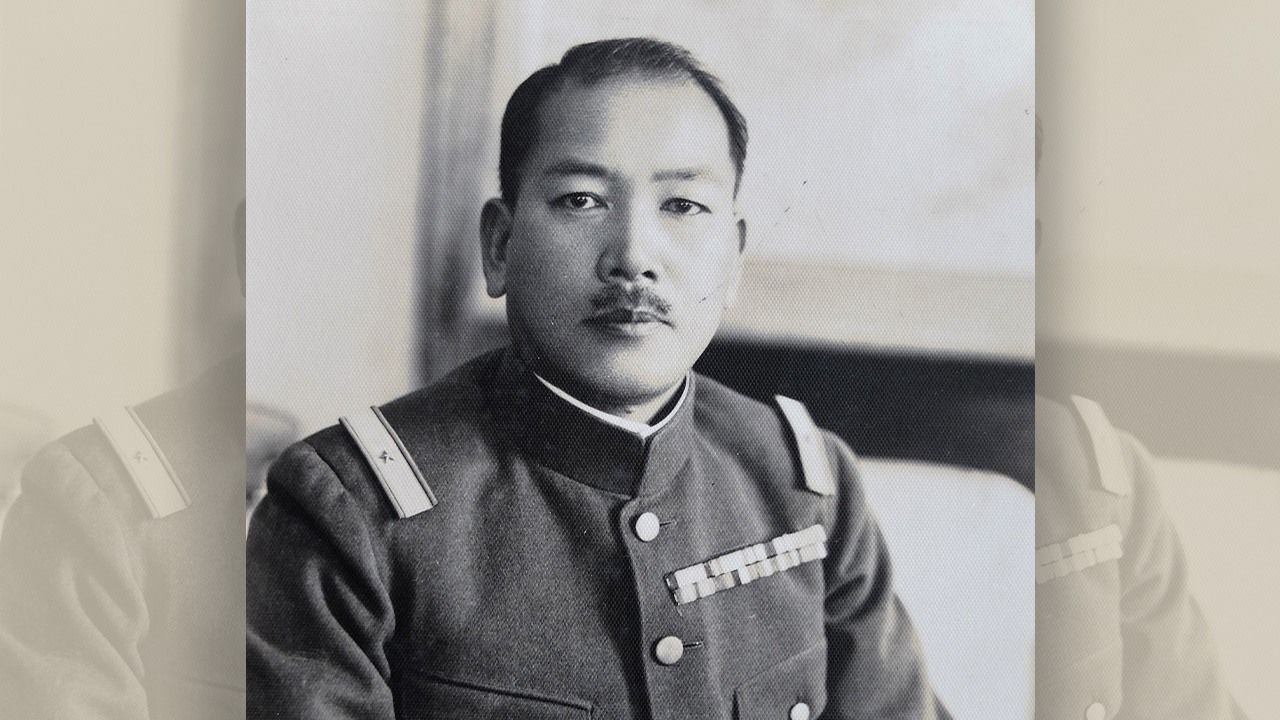

A Lesser-Known “Japanese Schindler”: Lieutenant General Higuchi Kiichirō

Politics People History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Statues to Honor a Hero

Recently, more people are acknowledging the achievements of Lieutenant General Higuchi Kiichirō (1888–1970), who saved Jewish refugees fleeing German persecution prior to the outbreak of World War II and helped impede the Soviet invasion of Hokkaidō after Japan’s acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration.

Higuchi Ryūichi, grandson of the late lieutenant general and professor emeritus at Meiji Gakuin University, established a committee to raise funds to erect statues to honor his grandfather’s achievements. Fundraising efforts extend beyond Japan, with appeals to Jewish people in Israel and the United States. The group hopes to gain wider attention for Higuchi Kiichirō’s deeds, and to spread international goodwill.

The statues should be completed by autumn 2022, with one to be erected in Izanagi Jingū, a shrine on the island Awaji, Higuchi’s birthplace, and another in Hokkaidō, in a still undetermined location that Higuchi hopes will have views of the Northern Territories, islands claimed by Japan but held by Russia since the end of the war. The group of 22 includes people in Awaji and Hokkaidō, together with Edward Luttwak, a world-renowned American expert on strategic theory, and Rabbi Mendi Sudakevich, head of the Jewish Center Chabad Japan. They have raised around ¥30 million in donations.

In March 1938, while commander of the Harbin Special Branch in the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo, Lieutenant General Higuchi enabled many Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany to cross the border from the Soviet city of Otpor (modern-day Zabaykalsk) into Manchukuo. He also provided them with food and fuel and arranged for their transit through the territory. This was two years before Sugihara Chiune issued 6,000 visas for Jewish refugees while he was vice-consul of the Japanese consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania.

At the time, Jewish people with German citizenship were permitted to transit Shanghai, yet the Manchukuo Foreign Office refused their passage, out of concern for Japan-German relations. But Higuchi insisted that Japan was not a vassal state of Germany, and nor was Manchukuo of Japan. He persuaded the Japanese government and military authorities to open an escape route to Shanghai, leading to an increase in refugees who chose the route. The Golden Book, which records the names of people who aided Jewish people and is permanently held by the Jewish National Fund in Jerusalem, states that 20,000 people were saved.

Sympathy for the Jewish Plight

Why did Higuchi work to rescue Jewish people? Prior to the rescue operation at Otpor, Higuchi expressed his support for founding a homeland for the Jewish people at the first Far East Jewish Conference, held in Harbin in December 1937, indicating his deep understanding and sympathy with the Jewish cause.

The background to this is described in his published memoirs. In 1919, Higuchi was sent as a special agent to Vladivostok, where he boarded in a Russian-Jewish home. Through his nightly discussions with young Jews, he developed strong bonds with them and became familiar with the problems they faced. In 1925, he was sent as military attaché to Warsaw, Poland, where he acquired a broad-minded international outlook. There he also witnessed the discrimination against and persecution of Jewish people, who accounted for a third of the city’s population.

Higuchi Kiichirō (at front right) while stationed as a special agent in Vladivostok. (Courtesy of Higuchi Ryūichi)

Despite strong local discrimination against people of color, Jews lodged and helped Higuchi, as well as Yonai Mitsumasa, a naval officer stationed in Warsaw from 1921, and Hyakutake Harukichi, an army officer who, like Higuchi, went to Poland in 1925 to study code-breaking techniques. Higuchi, who never forgot the hospitality he received, recounted this to his grandson Ryūichi when explaining why he helped Jewish people when they were in trouble.

Higuchi Kiichirō (front row, far right) during his time in Warsaw, when military officers of Japan and Poland developed strong bonds. (Courtesy of Higuchi Ryūichi)

According to his memoirs, Higuchi traveled to the Caucasus region on an inspection tour in 1928, visiting Tiflis (now Tbilisi) in Georgia. There, an elderly Jewish toy shop owner told Higuchi about the persecution of Jews, calling Japan’s emperor “a savior of Jewish people in their hour of need,” and praising Japanese people for their tolerance.

Undoubtedly, this experience had a deep impact on Higuchi when he helped Jewish refugees. In 1937, he was briefly stationed in Germany, where he felt strong misgivings about Nazi anti-Semitism.

Ulterior Motives to His Humanitarian Efforts

After the dispatch of troops to Siberia, Higuchi became a distinguished intelligence officer. Shiraishi Masaaki of the Diplomatic Archives Division of Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has researched Sugihara Chiune extensively. Shiraishi believes that Higuchi assisted Jews fleeing the Soviet Union partly to gain intelligence information. Shiraishi sought assistance from foreign experts to examine photos of Jewish people rescued through Otpor, many of whom they identified as Russian Jews.

Anti-Semitism was as strong in Russia as it was in Nazi Germany, even prior to the formation of the Soviet Union. In Harbin, there was strong mutual antagonism between Jews and White Russian émigrés, leading to frequent disputes. According to Shiraishi, Sugihara was well aware of the situation. In his book Sugihara Chiune: Jōhō ni kaketa gaikōkan (trans. Sugihara Chiune: The Duty and Humanity of an Intelligence Officer), Shiraishi describes Sugihara’s efforts in Kaunas, Lithuania, which aimed to protect Jews from the threat of Stalin. But he also claims that Sugihara was an intelligence genius who made use of Polish intelligence agents. If Higuchi Kiichirō also rescued Jews for both humanitarian and intelligence purposes, it shows his effectiveness as an anti-Soviet agent.

Nazi Germany raised objections with Japan, its Anti-Comintern Pact partner. Higuchi’s superior, Tōjō Hideki, then chief of staff of Japan’s Kwantung Army, rejected the German complaints on the grounds that Higuchi was only doing what was humanitarian. In this he was apparently convinced by Higuchi’s provocative challenge—do we believe it right to be Hitler’s lackey and to persecute the weak?—as well as the fact that the Japanese government did not subscribe to the racist ideology of Nazi Germany, despite the military pact.

Higuchi’s exploits are recorded in the Jewish National Fund’s Golden Book, but not on a par with Sugihara, who has been named Righteous Among the Nations, the highest honor awarded by the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial.

Luttwak states that many among the 20,000 Jews saved through the “Higuchi Route” went on to even become ambassadors and scientists in the United States and Israel. Amid the uncertainty and turmoil, nobody in Europe moved to protect the Jews—not even Britain’s prime minister, Winston Churchill. Consequently, 6 million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust. In contrast, Higuchi’s audacious initiative “deserves to be widely honored.” In lending his support for Higuchi’s recognition, Luttwak acknowledges that “There were good Japanese soldiers with humanitarian beliefs.”

Daniel Friedman (right), the son of a Jewish refugee who escaped using the “Higuchi Route,” meets Higuchi Ryūichi, professor emeritus at Meiji Gakuin University and grandson of the late Higuchi Kiichirō, in Tel Aviv, Israel, on June 15, 2018. (© Jiji)

Foiling Stalin’s Hokkaidō Ambitions

Higuchi was assigned to the Sapporo-based 5th Area Army, entrusted with protecting Japan’s north, including Hokkaidō and the Japanese territories of the Chishima (Kuril) Islands and southern Sakhalin, which Japan called Karafuto. On August 18, 1945, he led the defense of Shumshu island against the Soviet invasion. Higuchi’s own initiative, this ignored a ceasefire order from the Imperial Headquarters following Japan’s acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration and the imperial rescript ending the war. As the army’s foremost counter-Soviet intelligence officer, he was acutely aware of their ambitions.

Higuchi Kiichirō (front row, center), visiting the Karafuto Divisionin October 1944 in his role as commanding officer of the 5th Area Army. (Courtesy of Higuchi Ryūichi)

Higuchi Kiichirō (center), inspecting the tundra region of northern Karafuto (Sakhalin) as commanding officer of the 5th Area Army. (Courtesy of Higuchi Ryūichi)

At the Yalta Conference, seven months prior to Japan’s signing of the Instrument of Surrender, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had made a secret agreement sealing his intention to occupy Karafuto, the Kuril Islands, and Hokkaidō. On August 16, he demanded that US President Harry Truman allow the Soviet Union to occupy Hokkaidō, north of a line between Rumoi and Kushiro. His demand was rejected, yet he still issued orders to prepare the Sakhalin-based 87th Rifle Corps to invade Japan.

Higuchi gave orders to resist the Soviet forces, who landed on Shumshu Island on August 18, thereby delaying Soviet capture of the Kuril Islands and foiling their plans to invade Hokkaidō. After abandoning hope of capturing the main prize, Stalin directed troops from southern Sakhalin to deploy to Etorofu, and the Soviets succeeded in the bloodless capture of Kunashiri, Shikotan, and the Habomai Islands. Their illegal occupation of these islands continues to this day. Without Higuchi’s resolve to mount a counterattack, it is highly likely that the Soviets would have invaded Japan and it would have become a divided country.

Saved from the War Trials

With his hopes dashed, Stalin sought to hand Higuchi over to the Tokyo Trials (the International Military Tribunal for the Far East) to be tried for war crimes, but this was vetoed by General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers.

Some speculate that this was due to opposition by the World Jewish Congress. But in his memoirs, Higuchi states that following the war, during his interrogation, he was told by a US Counter Intelligence Corps officer that it was the British who supported him, blocking Soviet demands for his arrest.

Higuchi recounted that, while in Poland, he worked with Britain’s Edmund Ironside, then a major general. Their interactions included exercise inspections and intelligence sharing regarding the Soviets. Ironside later rose to the position of chief of the Imperial General Staff as field marshal. Higuchi believed it was Ironside who pressured MacArthur to show him leniency.

Japanese cryptological cooperation with Poland, which began with Higuchi’s dispatch, led to dramatic improvements in Japanese cryptography, while intelligence sharing with Poland developed from the time of Sugihara. Toward the end of World War II, Poland provided the Japanese military attaché in Sweden, Onodera Makoto, with details of the secret Yalta agreement for the Soviet Union to enter the war against Japan. Higuchi’s pioneering work in this field explains his natural talent as a counter-Soviet intelligence officer.

Owing to his military career, Higuchi Kiichirō has not received the wide recognition of the diplomat, Sugihara Chiune. But on July 9, 2021, a symposium was held to mark the launch of the Committee to Honor Lieutenant General Higuchi Kiichirō. As a Japanese, I am pleased to see this increasing global reappraisal of Higuchi.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Lieutenant General Higuchi Kiichirō. Courtesy of Higuchi Ryūichi.)