Many Remain Unvaccinated in Japan on Eve of Olympics

Society Health Tokyo 2020- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Delta Variant Brings Increased Threat

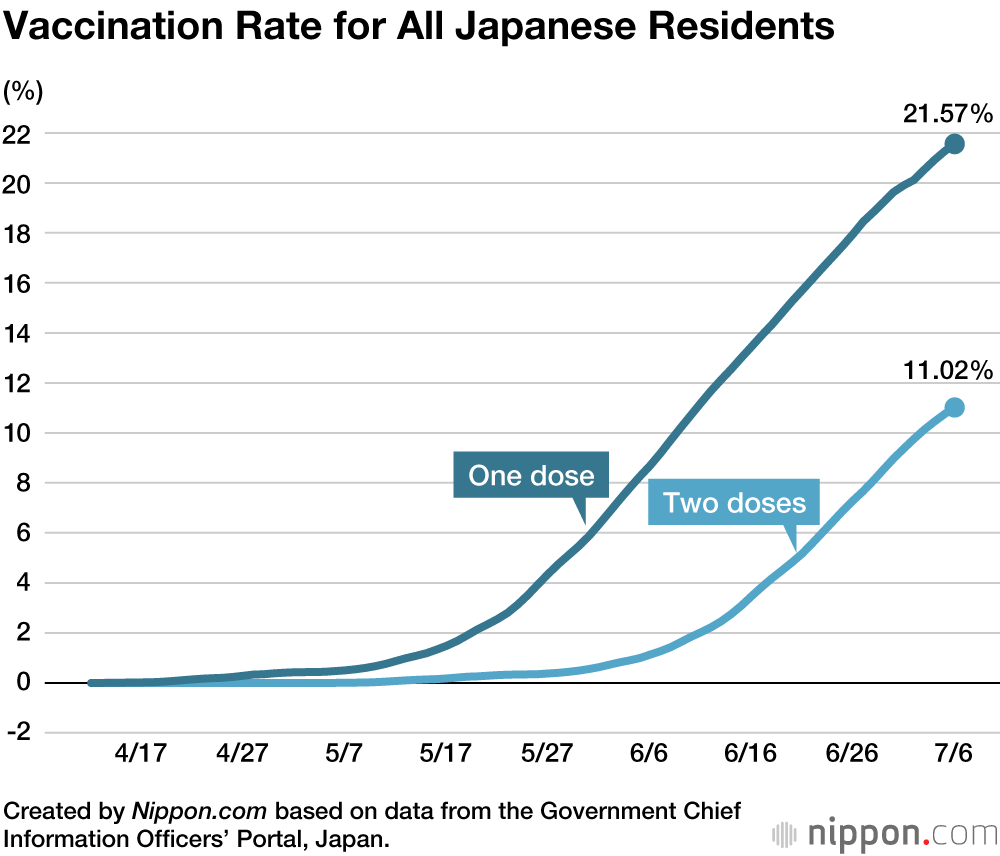

With the Tokyo Olympics set to begin on July 23, the Japanese government set a target of completing COVID-19 vaccinations for seniors aged 65 and over—the group at most risk of developing severe symptoms—by the end of July. As of July 6, a total of 69.4% of seniors had received one dose of vaccine and 37.9% two doses. However, the overall pace of vaccination dropped as supply started to fall behind demand, with the government suspending applications for workplace vaccinations and local authorities halting reservations. Also as of July 6, 21.6% of all Japanese residents had received one dose and 11.0% two.

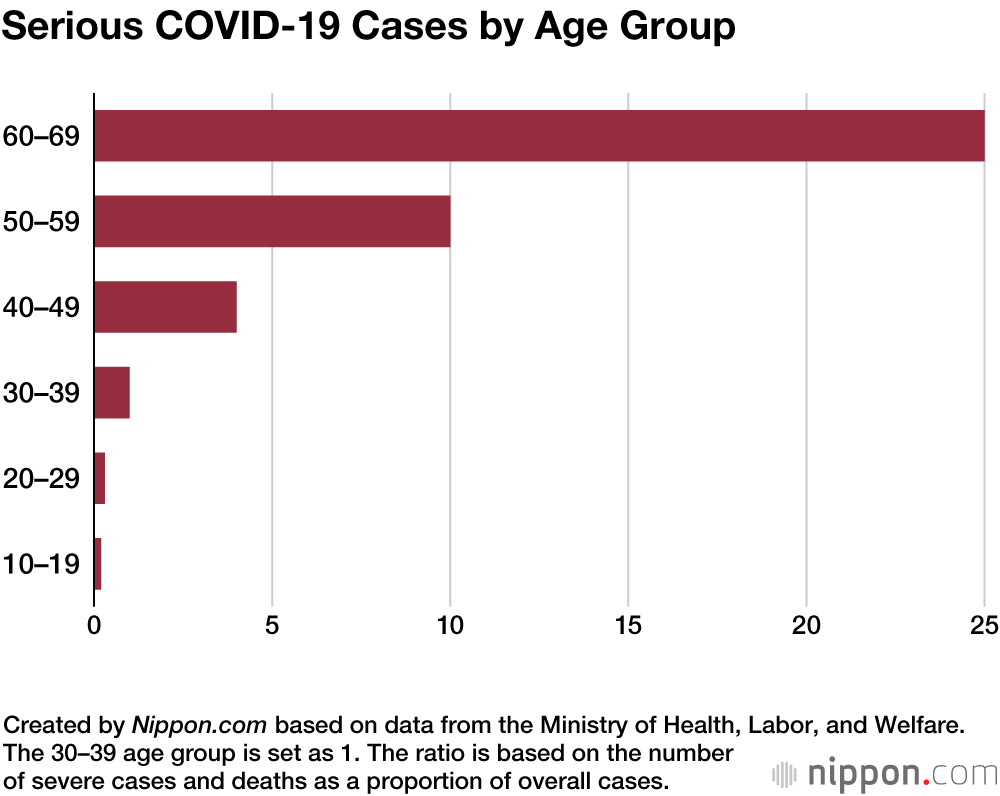

Omi Shigeru, the chair of the government’s COVID-19 advisory panel, has noted that severe cases are rising among people in their forties and fifties, due to the spread of the Delta variant, so vaccinating this cohort is an urgent task.

Feeling Left Behind

Hishida Hajime (who asked that his real name not be used), a 59-year-old self-employed resident of Yokohama, Kanagawa Prefecture, received his vaccination voucher from the city at the end of June. He was overjoyed for a moment, thinking he would surely be able to reserve a vaccination, but in a close reading of the fine print, he found the following sentence. “A notification on the vaccination period and reservation is due to be sent in around August.”

Yokohama has nearly 1.2 million people aged in their forties and fifties. If he had received his voucher earlier, Hishida might have been able to take advantage when some slots were not being taken up for a time at the government mass vaccination centers in Tokyo and Osaka. As he is self-employed, there was no chance to receive a workplace shot. “They’re putting big corporations first and leaving people like the self-employed and single mothers until later. I’m feeling quite uneasy,” he admits. But in the end, all he can do is rely on the local government.

Tokyo’s new daily cases were approaching 1,000 when the capital entered its fourth state of emergency on July 12. Shortly ahead of this, on July 8, the government, International Olympic Committee, and other involved parties made the decision that Olympic events in the prefectures of Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama, and Chiba would take place without spectators. “That’s only to be expected, under the circumstances,” Hishida asserts. It was thought that otherwise there would be a great influx of spectators from other prefectures for popular events like baseball and soccer. Near the baseball venue of Yokohama Stadium is the country’s biggest Chinatown, as well as the Noge district, which is full of bars and restaurants that could have become inundated with excited fans.

Yokohama Stadium, the Olympic baseball venue (left), and the city’s Noge district. (© Kyōdō)

While mass movement of people has been averted for the moment, Hishida has another concern. This is the reliability of the “bubble” method for isolating the 55,000 foreign athletes and others connected to Olympic teams. “It’s impossible to manage them individually. And there were reports that not all the drivers of the buses taking them to and from venues have been vaccinated.” Not having been vaccinated himself, Hishida remains anxious about the games. “It seems to me, basically, that the most effective preventive measure would have been to cancel or postpone them.”

When asked for his opinion on the event, however, Hishida says, “I love the Olympics themselves. I’m really looking forward to the men’s 100-meter dash. But still, now’s not the right time. I’m frightened about what might happen afterwards. How will future generations judge this decision?”

A Sense of Unfairness

There are also those who have managed to get vaccinated. Satō Yoshitarō (an alias) is a 57-year-old living in the Tsukishima district of Chūō, Tokyo. He had thought he would need a voucher to do so at a private practitioner, but learned online of clinics accepting reservations without vouchers, and rushed to sign up. This meant he is set to receive his second shot on July 27, while the Olympics are ongoing. “I was panicking when the Delta variant started spreading, but now I’m feeling a bit calmer,” he says.

The Chūō municipal government started reservations for its own group vaccinations of residents aged 40–59 on July 2, but it was fully booked after just five minutes. After this, reservations have only been intermittently available. Many people are missing out due to the stalled group vaccinations, while others have been accepted by clinics without vouchers, and Satō comments apologetically, “A lot of residents are probably feeling both nervous and a sense of unfairness.”

Facing Tokyo Bay, just a kilometer from Tsukishima, a cluster of high-rise buildings surrounded by fencing has appeared. This is the Olympic Village. While jogging around the area, Satō says he cannot help looking out to see if there are more foreign people around. Strict rules mean athletes are unlikely to go out into the city, but Satō says he is scared that media representatives will, due to looser controls. Tsukishima has a street famous for its pan-fried monjayaki dish, which could attract some groups.

The Olympic Village in Tokyo. (© Kyōdō)

Despite being right beside the Olympic Village, there is no festive mood in Tsukishima. “There’s no real sense that the Olympics will take place in Tokyo. I feel sorry for the athletes, who will compete without being able to properly do their final training.” Satō plans to avoid going outside during the games and spend the whole time watching them on television with his wife.

“Tomorrow It Could Be Me”

There are also people in this age group who do not wish to get vaccinated. Yano Kenji (not his real name), a 48-year-old soba restaurant owner in Saitama Prefecture, is concerned that the clinical trials were too short, and does not plan to get vaccinated. He takes firm measures to prevent the spread of infection in his restaurant, including ensuring the use of masks and disinfecting and ventilating the premises.

Quasi-emergency measures have been lifted in his part of Saitama Prefecture, and alcohol can be served until eight in the evening. However, he is worried that the state of emergency in Tokyo may lead to quasi-emergency measures being reimposed locally. “It makes a huge difference to my sales, whether I can sell alcohol or not,” he says.

In Tokyo, establishments serving alcohol have faced repeated requests to suspend operations. “As there’s pressure on liquor suppliers not to sell to bars and restaurants, the businesses are in real trouble. It’s so sad, and it doesn’t feel like someone else’s problem. I think tomorrow it could be me.”

Washida Taeko (again an alias), a 61-year-old Tokyo resident, is set to be vaccinated on August 17. This is too late for the Olympics, but she says, “I’m taking precautions in my own way, and if I focus too much on my worries, I won’t be able to get anything done.” She was more concerned about her own event plans falling through due to the state of emergency. She also expressed her mixed feelings about the games. “Allowing spectators in this situation is unthinkable, but when I think about the athletes who’ve worked so hard to achieve their goals of competing, I feel I’d like to allow it, so I don’t know what to say.”

The Unreached Homeless

Poverty is a reason stopping some people from getting vaccinated. Takeishi Akiko of the nonprofit organization Médecins du Monde is involved in activities like distributing food and offering medical advice to impoverished people from a base in Ikebukuro, Tokyo. She says that she feels a lot of information is not reaching them.

From late May, she conducted a survey in which 58% of respondents said they wanted to be vaccinated. Among the remaining 42%, who either replied negatively or did not know, there were comments like “I’d like to if it was free,” I don’t think I can get it without an address and ID,” and “I don’t know anything about side effects.”

Vaccination vouchers are sent out by municipalities to the registered addresses of residents, so there are concerns that they cannot physically reach the homeless. The Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare called on local authorities at the end of April to coordinate with support groups to ensure vaccinations are possible, but initiatives have only just begun. Takeishi says that even among those with fixed addresses receiving support, many people do not have mobile phones, so there also needs to be a full service for helping with reservations.

More Infectious

One factor behind Tokyo’s return to a state of emergency is the rising proportion of cases involving the Delta variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Miyasaka Masayuki, a guest professor in immunology at Osaka University’s Immunology Frontier Research Center, says that the Delta variant is around 1.8 to 2 times more infectious than previous variants and multiplies extremely rapidly, so is more likely to lead to severe consequences.

While vaccination will limit serious illness among seniors, Miyasaka says of people in their forties and fifties, “They could somehow deal with earlier variants, but with the more infectious Delta variant, it’s coming to the point where their immune system is no longer enough.” Although there are limits to the supply, he says that the workplace vaccination program should be used more to ensure this cohort is covered.

(Originally published in Japanese on July 13, 2021. Banner photo: COVID-19 vaccinations of seniors in Kitaaiki, Nagano Prefecture. © Kyōdō.)