Ono Yōko and “Hiroshima Sky Is Always Blue”

Culture Society Art- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Drama of War and Blue Skies

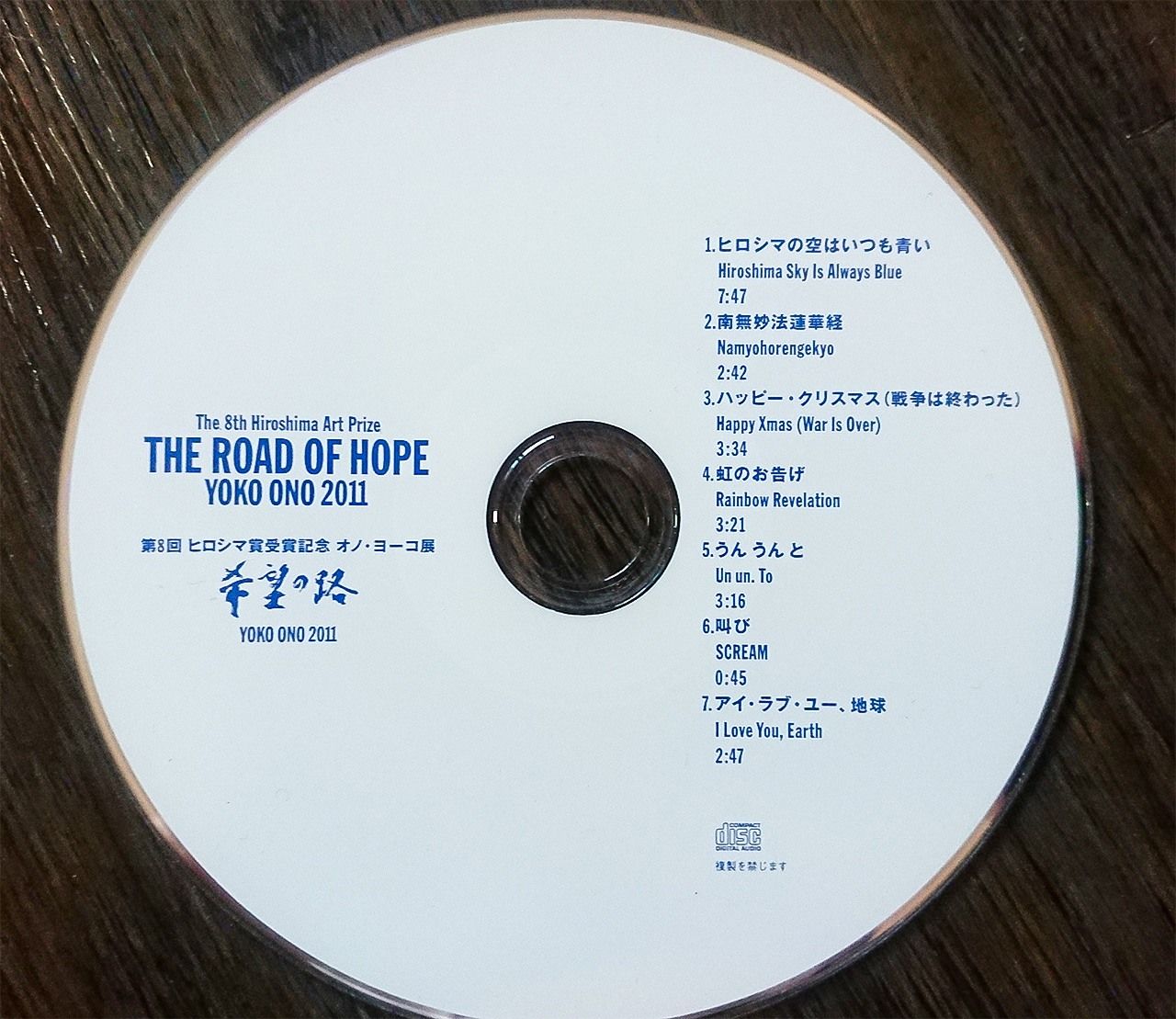

The only official recording of “Hiroshima Sky Is Always Blue” is on the CD accompanying the catalogue of Ono Yōko’s 2011 solo exhibition Road of Hope at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art. The exhibition was held to commemorate her being awarded the eighth Hiroshima Art Prize for artists who have contributed to peace.

After a solemn pealing of bells, we hear Ono Yōko’s voice. “John, we are here now together,” she says. “Bless you. Peace on Earth. Strawberry Fields Forever.” A cacophony of traditional musical instruments and strange groans and screeches follow, interspersed with the voices of a chorus led by Paul McCartney and Yōko’s voice repeating the enigmatic phrase: “Hiroshima sky is always blue.”

The CD included in the catalog of Ono Yōko’s solo exhibit at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art.

The haunting song was originally created for the off-Broadway play Hiroshima, which premiered in the fall of 1997. Written by writer/director Ron Destro in 1994, the play portrays the fate of Hiroshima families around the time the atomic bomb was dropped on the city on August 6, 1945. The play was originally meant to premier in 1995 to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the bombing, but financial problems delayed the opening to 1997. Destro asked Ono Yōko to write some of the music for the personal stories presented in the play, including one about a young girl modeled on the famous Sasaki Sadako, who was exposed to the radiation of the bomb when she was only two years old and died 10 years later of leukemia. During the eight months Sadako spent in the hospital before her death, she undertook a project to fold 1,000 paper cranes, a traditional project often undertaken in the hopes of fulfilling a wish.

Destro had lived in Japan for an extended period and says that in writing the play he referred to “Hiroshima,” an in-depth article documenting the devastation of the bomb written by the American journalist John Hersey, and Children of the Atomic Bomb: Testament of the Boys and Girls of Hiroshima, compiled by Osada Arata, a prominent Japanese educator. Destro also incorporated within the play references to the spirit of Bushidō, haiku poetry, and other elements of Japanese culture. Looking back, he says his intent was to personalize the many people who died and suffered as a result of the bombing in a way that could never be conveyed by statistics alone.

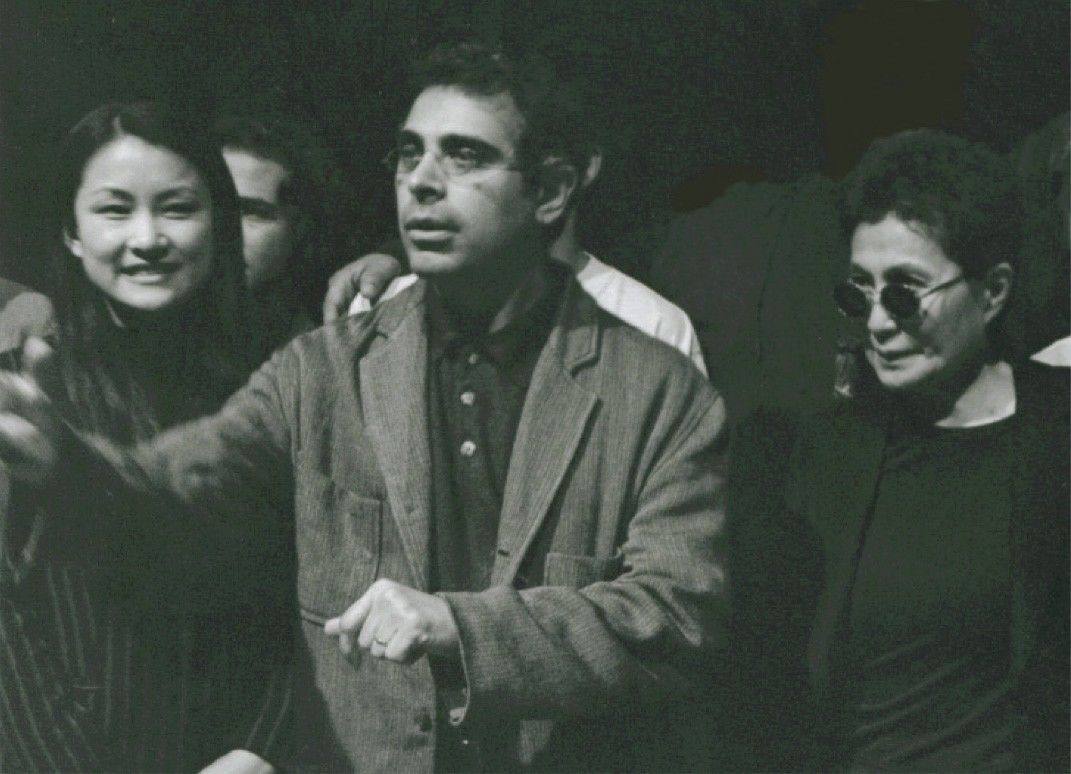

Ron Destro speaks at the off-Broadway opening of Hiroshima. Ono Yōko stands to his left. (Photo provided by Ron Destro)

In a September 1995 edition of the monthly magazine Bungei Shunjū, Ono Yōko recounts an episode about the Hiroshima production. “I was amazed at how this American sought to convey the tragedy of the atomic bomb from a Japanese perspective. The play is a vivid depiction of what the people of Hiroshima experienced and how they suffered. . . . Ideas swirled in my head as I entered the recording studio, but it was the imagery of ‘Hiroshima Sky is Always Blue’ that came immediately to the fore.”

A still photo of a scene from Hiroshima. (© Jonathan Slaff)

Yōko’s maternal great-grandfather was Yasuda Zenjirō, founder of the Yasuda zaibatsu. Her paternal grandfather was Ono Eijirō, head of the Industrial Bank of Japan. With this prestigious background, and a globe-trotting banker for a father, Yōko spent a part of her childhood in the United States. She and her family returned to Japan when war became imminent. Despite her family’s wealth, Yōko has memories of food being scarce in the countryside where she had been evacuated. Still, she says, the sky was blue, and after she returned to the ruins of Tokyo, the sky was still blue. She learned of the atomic bombings through the newspapers. “And yet, Hiroshima came back to life. Thinking of that reminded me of the shining blue skies within my own heart.”

Of Yōko’s “blue sky” memories, music critic and longtime friend Yukawa Reiko says, “It is an image linked to the terrors of war. I recall watching the B-29 bombers flying in the blue sky overhead when I was evacuated to Yonezawa in Yamagata Prefecture. I think Yōko and I share the same memory of horrified fascination.”

The Beatles, London, New York, and Hiroshima

While it was not possible to stage Hiroshima in 1995, the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the war, an off-Broadway run of six weeks was finally achieved in late 1997. In addition to “Hiroshima Sky Is Always Blue,” Yōko’s songs for the play included a selection from her album Rising. The play was given wide acclaim. The New York Times praised Yōko’s music in an October 17, 1997, review, noting that the selection from Rising “is interspersed delicately with the sad family stories woven by Mr. Destro . . . Ms. Ono’s discordant musical style does not run against the grain: it sharpens the portrait of a world in tatters.” The Village Voice rated Hiroshima as one of the top 20 plays of the season, and the Kennedy Center in Washington DC selected the play as one of three that year to receive its New American Award.

There is a dramatic story to the making of “Hiroshima Sky Is Always Blue,” detailed in the Bungei Shunjū interview.

In January 1995, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, Ono Yōko, and her son Sean met in London to discuss matters concerning Apple, a company the Beatles had established in the 1960s. Later, Paul invited Yōko and Sean to spend the night at his home in the London suburbs. This was around the time work was progressing on the Beatles Anthology, a retrospective project of the Beatles history, and the rancor of the past had long since given way to more amicable relations. The next morning, Paul and Yōko decided to hold a jam session in his personal studio. It was at this time that Yōko said she wanted to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the war by having them all, including their children, join in a rendition of her “Hiroshima Sky Is Always Blue.”

Everyone took part, with Paul directing and playing bass and his wife Linda playing the organ. Their four children participated as well, with James on the guitar and Heather, Mary, and Stella, who would soon emerge as a well-known designer, on percussion.

To Sean, Paul assigned the harpsichord that had been played in several Beatles tracks, and asked him to also use a bell, in a manner like that of the tolling bells featured in John Lennon’s “Mother” and “Starting Over.”

Just as they were getting ready to start, Paul noticed a copy of the music for “Strawberry Fields Forever” in a corner of the studio—something that shouldn’t have been there, but was. Yōko recalls that moment, saying, “It was as if John was with us,” and that is what led to the monologue opening of the “Hiroshima” song. Her son Sean says, “It was more the result of our reconciliation after twenty years of bitterness and feuding bullshit. It was incredible working with Paul. Here were these people who had never played together actually making music” (as quoted in Keith Badman’s The Beatles: The Dream Is Over). A portion of the music recorded in this session was broadcast on an NHK news program on August 6, 1995.

“Life and Death” on a Magical Stage

“Hiroshima Sky Is Always Blue” has been performed live only once, at an Ono Yōko concert held on October 7, 1995, on the Takabutai stage of the Itsukushima Shrine at Miyajima in Hiroshima. A World Heritage site, Itsukushima Shrine extends out into the Inland Sea, appearing at high tide to be floating on the water. Yukawa Reiko, who attended the concert, remembers it well. “The moon rose from behind the shrine and we could hear the cries of deer in the distance. It was magical.”

Titled the “Yōko Ono/Ima/Memorial Concert,” the event commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing and the 1,400-year anniversary of the shrine’s construction. The roughly 1,100 seats arranged on the seaside of the platform extending from the shrine toward the great torii gate farther out in the bay were promptly sold out. “Visitors are amazed when I tell them about the concert,” says Fukuda Michinori, a senior priest of the shrine. The Takabutai is normally reserved for the exquisite and solemn bugaku dance performances dedicated to the gods, but the chief priest at the time gave special permission for Ono to perform on the sacred stage.

Itsukushima Shrine’s Takabutai stage is a designated National Treasure. (© Fujisawa Shihoko)

The concert was broadcast by the media and fan sites. Ono Yōko appeared in a purple kimono while the members of the band Ima, which included her son Sean, wore the traditional men’s formal kimono attire of haori hakama. The primarily acoustic performance consisted of nine songs, with “Hiroshima Sky Is Always Blue” the seventh to be performed. The two-hour concert was covered in an article in the local Chūgoku Shimbun published on October 8, the next day. “The performance of avant-garde music was at once a commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of the dropping of the atomic bomb, an expression of prayer for the repose of the victims, and a celebration of the 1,400-year anniversary of the shrine’s construction. . . . Traditional instruments and an anguished manner of song combined to create an ethereal expression of life and death.” Said one person who attended the event, “I’m a Beatles fan and I wanted to see John Lennon’s son perform. The quiet atmosphere made us listen attentively.”

The Chūgoku Shimbun later carried an interview of Ono Yōko on October 14, 1995.

“I focused on striking a balance between the ‘life’ of the 1,400-year-old shrine and the tragic death of the atomic bomb victims. The setting looking out over the water and up to the sky with mountains in the background gave us a sense of harmony with nature as we performed. In this milestone year (marking the fiftieth anniversary of the atomic bombing), I wanted to convey to the world once again the message of ‘No more Hiroshima.’” It was important to her, she said, that her children accompanied her to Hiroshima. Sean, who was with her at the interview, spoke of the tears he shed as he gazed upon the Atomic Bomb Dome for the first time. One of Ono’s children by her first husband, her daughter Kyōko, also attended the concert. “I heard that she was a schoolteacher and had been able to get a day off to attend,” recalls Yukawa. The two had long been estranged but had reconciled by the time of the concert.

The shrine’s anniversary celebrations had been postponed for two years due to typhoon damage, and so just happened to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the atomic bombing. The proposal to invite Ono Yōko to perform was made by a citizen volunteer. Funds for the event were donated by local businesses and supporters, while Ono Yōko performed for free. In the following year, 1996, the Atomic Bomb Dome and Miyajima, including Itsukushima Shrine, were designated as World Heritage sites by UNESCO. Ono Yōko’s performance contrasting life and death thus coincided with the World Heritage registration, another factor contributing to the historic significance of the concert. Despite this, only a few recordings and photographs of the event are publicly available today, as Ono appears to own the rights to such materials.

Satō Kyōko, who headed the committee that produced the concert and who is now professor emeritus at the Elisabeth University of Music, arranged for part of the concert proceeds to be donated to charity. In November 1995, she personally delivered the donation to the Gyeongju Nazareth Home in South Korea. The home is a care facility for elderly Japanese women who were unable, in the confusion that followed Japan’s defeat in the war, to return to their home country. Says Satō, “Because we experienced the atomic bomb, we tend to see only ourselves as the victims of that terrible war. I made that donation to show that we were not the only victims.”

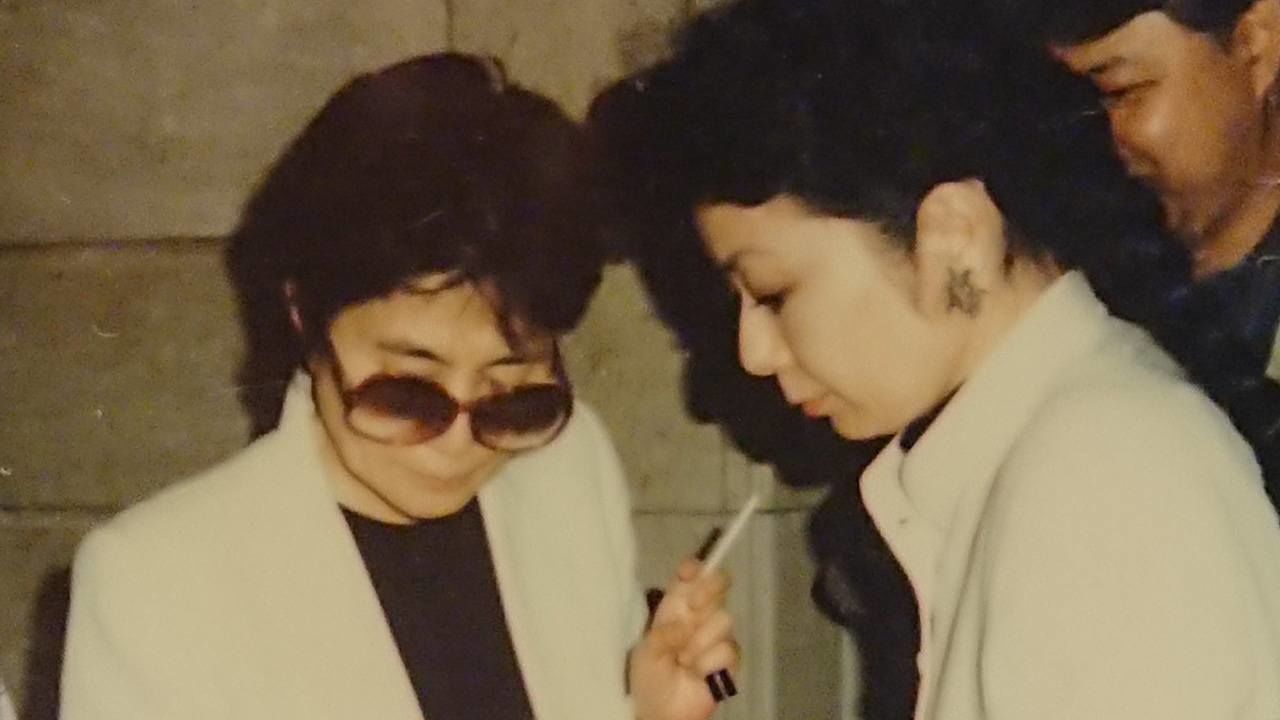

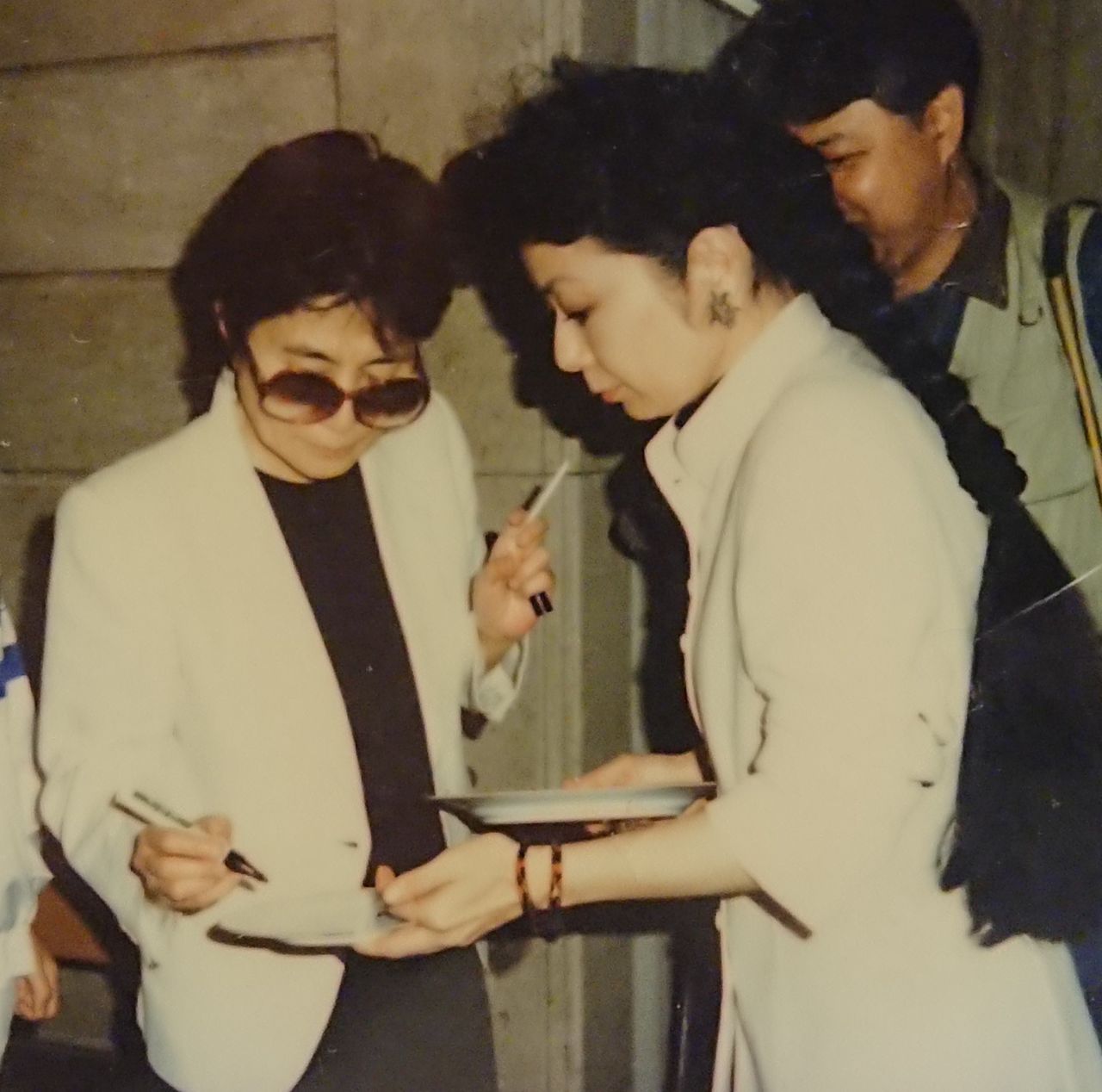

Ono Yōko (left) and concert committee chair Satō Kyōko. October 1995, Miyajima. (Photo provided by Satō Kyōko)

A Glimpse of the Real Ono Yōko

“Hiroshima Sky is Always Blue” remains unpublished to this day. A 1995 issue of The Beatles Book, a British fan club publication (currently discontinued) and other publications reported that Ono Yōko was concerned about her children’s involvement in the song and did not want it commercialized. At the same time, they also reported that she might consider publishing it in some other form. Given that any kind of official sales would require negotiating over the rights with Paul McCartney, it is likely that Ono found the option of a free performance in Hiroshima to be more appropriate.

Music critic and close personal friend Yukawa Reiko. (Photo provided by Office Rainbow)

Who is the “real” Ono Yōko? Says her friend Yukawa, “She may seem to be always clad in armor, but there is a soft spot within her. She is actually an incredibly kind person and easily hurt. Her son Sean has known this about her since he was small. He was only five years old when John died, but even then he tried desperately to encourage his mother.”

Sean was 20 years old at the time of the 1995 Itsukushima concert. Yukawa remembers asking him, “Do you understand Yōko’s music?” She was surprised when he responded, “I think Mom’s music is good.” At a time when the whole world seemed to be anti-Yōko, John Lennon understood and supported her. Yukawa says, “Sean appears to have the same ear and sensibility as his father. The fact that he has forged his own way as a musician is testimony to that.”

The “Hiroshima Air Clock” installation by Ono Yōko in the Hiroshima Television lobby. Hiroshima city. (© Fujisawa Shihoko)

Ono Yōko has contributed her own artwork to the city of Hiroshima. The “Hiroshima Air Clock” marking the date and time of the atomic bombing can be viewed in the lobby of the Hiroshima Television building outside the north entrance of the JR Hiroshima Station. Compared to her artwork, Ono Yōko’s music is at once avant-garde and “punkish,” according to Yukawa, and sometimes difficult to understand. Still, it can be interpreted as just another form of expression of the sensibilities that pulsate through all of her creative work. Sony Music Labels, which manages Ono’s musical compositions, is hopeful that someday it will be able to publish “Hiroshima Sky Is Always Blue” in some form or other. The song may be buried in a tiny corner of history right now, but it deserves to be preserved in our memories.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Ono Yōko, at left, and Miyajima concert committee chair Satō Kyōko in October 1995. Photo provided by Satō Kyōko.)