Miyazaki Hayao and His Mentor Ōtsuka Yasuo: Learning the Fascination of Animation

Culture Entertainment Manga Anime- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Old Friends Pass Away

In November 2016, the media was set abuzz when reports emerged that Miyazaki Hayao had changed his mind about retiring from filmmaking and was planning a new feature-length animation. The next year, production began on How Do You Live? Four years later, the movie is still not finished, and may not be released until 2023.

Miyazaki’s previous film, The Wind Rises, came out in July 2013. In the eight years since, several of his key team members have passed away, including animators Shinohara Masako and Futaki Makiko and color designer Yasuda Michiyo. In April 2018, director and long-time collaborator Takahata Isao died at the age of 82.

The loss of animator and director Ōtsuka Yasuo, who died in March 2021 just months shy of his ninetieth birthday, was of particular note for his influential relationship with Miyazaki. When Miyazaki was a new face at Tōei Animation, Ōtsuka acted as his mentor. The pair were active in the labor union together, becoming good friends and creative partners. I knew Ōtsuka personally for around 30 years, and I often asked him about his relationship with Miyazaki, making notes of his answers. Here, I would like to talk a little about that relationship.

A Chance to Shine

Miyazaki once said of Ōtsuka, “He taught me the fascination of animation, as well as how to begin developing the eye of an animator.”

In 1965, studio heads at Tōei Animation tapped Ōtsuka to oversee his first feature-length film, and against the wishes of his bosses he picked Takahata Isao, then an unknown, to director the film. He also approved the promotion of newcomer Miyazaki in a main role of scene design and key animation, playing a part in bringing the two future Studio Ghibli directors together. Other exceptional staff members like Okuyama Reiko and Kotabe Yōichi also joined up, and Ōtsuka’s personality and leadership were important in uniting the group for the production.

Disputes between management and workers repeatedly delayed the production, but in 1968 the film was finally released as Taiyō no ōji horusu no daibōken (The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun). Poor box office earnings, however, meant that many in the production team were demoted. In 1969, Ōtsuka moved to A Production (now Shin-Ei Animation). Two years later, Takahata, Miyazaki, and Kotabe followed him to work on a television version of Pippi Longstocking. This plan fell through in the end, but the four collaborated instead on the 1972 short film Panda kopanda (Panda! Go Panda!). Ōtsuka remained at A Production when the other three moved next to Zuiyō Enterprises (now Nippon Animation) for a 1974 television production of Arupusu no shōjo Haiji (Heidi, Girl of the Alps). Apparently, Ōtsuka suggested both Pippi Longstocking and Heidi to Takahata.

Takahata said of Ōtsuka, “Although we were not always working together, whenever I reached a turning point, Ōtsuka would always appear and invite me to move in a new direction. He’s the person who helped me most.” One can imagine that Miyazaki felt similarly.

Developing His Style

In 1977, Miyazaki took on his first role as director for the television series Mirai shōnen Konan (Conan, the Boy in Future), released the following year, on condition that he could invite Ōtsuka as animation director. This was a Nippon Animation production, and Ōtsuka was then an executive at Shin-Ei Animation. There was some opposition to him working on a rival’s project, but Ōtsuka said he wanted to support Miyazaki and worked as animation director on all 26 episodes. As with Takahata’s debut, Ōtsuka’s efforts were indispensable.

From Conan onward, one of Miyazaki’s greatest trademarks was his use of dynamic action and effects that give a sense of three-dimensional space and actually being on the scene—such as in mid-air fight scenes or battles with giant creatures. This was an animation technique that Ōtsuka specialized in for Tōei Animation features. In working together with Ōtsuka, Miyazaki absorbed the technique, refining and advancing it to become part of his directing style.

The title character of Mirai shōnen Konan (Conan, the Boy in Future). (© Nippon Animation Co., Ltd.)

After Conan, instead of returning to Shin-Ei, Ōtsuka moved on to Telecom Animation Film. This time, he made the call to Miyazaki, who was tapped to direct his first feature, the 1979 The Castle of Cagliostro. Once again, Ōtsuka was animation director, as he was for the 1981 film Jarinko Chie (Chie the Brat), which Takahata directed and Kotabe also worked on.

One could say that this laid the ground for the founding of Studio Ghibli in 1985. However, Ōtsuka never joined Ghibli, remaining at Telecom until his later years, and providing guidance for a multitude of young filmmakers.

“Notes” Becoming Films

Intended as Miyazaki’s last film, The Wind Rises was based on his manga with the same title (Kaze tachinu in Japanese) that appeared in the monthly magazine Model Graphix from 2009 to 2010. The subtitle was Mōsō kamubakku (Daydream Comeback). But what was it a comeback from?

From the 1970s, Miyazaki contributed illustrations to the model magazine Hobby Japan. In 1981, under the title “Boku no sukurappu” (My Scraps) he created illustrations and wrote essays based on his great knowledge of weapons and aircraft for a fan newsletter for Tokyo Movie Shinsha (now TMS Entertainment). He took this interest further with a spot called “Miyazaki Hayao no zassō nōto” (Miyazaki Hayao’s Miscellaneous Notes) that debuted in the November 1984 edition of Model Graphix—this became a manga midway through the run. Here he imagined not only machines and weapons, but the people and military forces who used them.

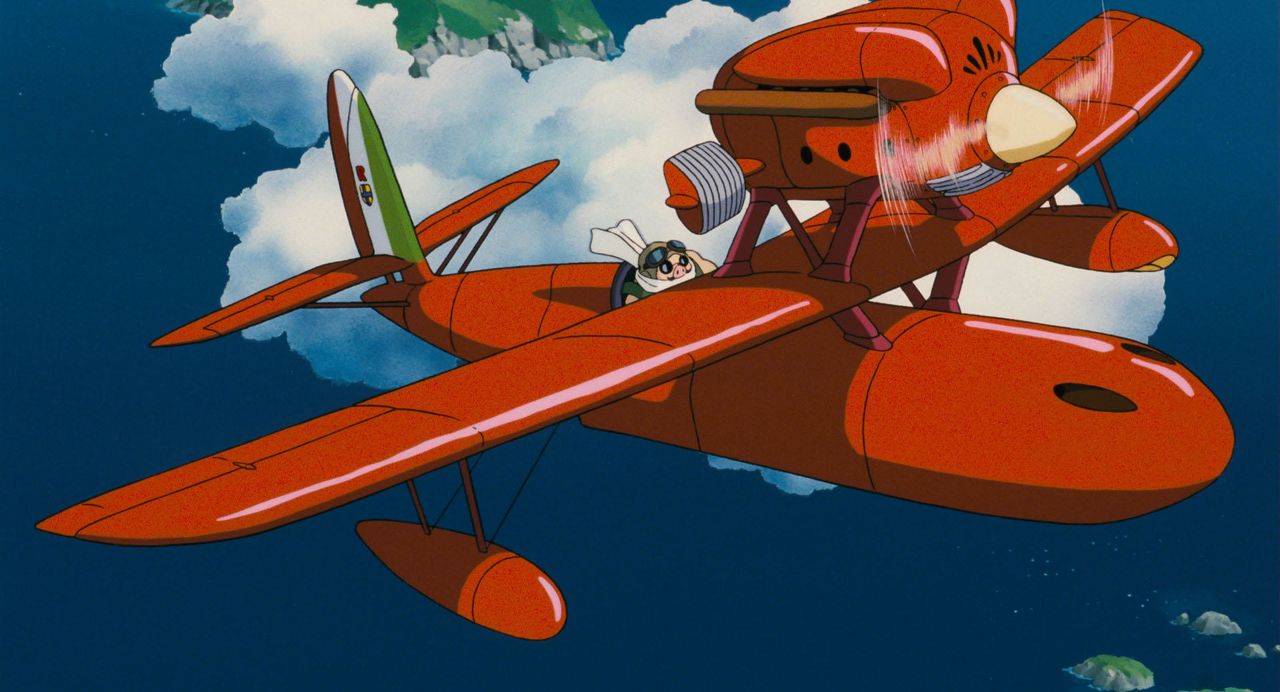

However, with the founding of Studio Ghibli in 1985, preparations for the following year’s release of Laputa: Castle in the Sky interrupted the manga’s run. Including further long hiatuses for the productions of My Neighbor Totoro (1988) and Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), the series continued until 1990. The 1992 film Porco Rosso was based on a mid-length manga Hikōtei jidai (The Age of the Flying Boat) that appeared as the fourteenth to sixteenth instalments of the “Miscellaneous Notes.”

The titular pig soars through the sky in Porco Rosso. (© 1992 Studio Ghibli•NN)

When it was published in book form in 1992, an extra story “Buta no tora” (A Pig’s Tiger) was added. A continuation, “Hansu no kikan” (The Return of Hans) appeared in the magazine in 1994, and then another six-episode story Doro mamire no tora (Tigers in the Mud) was released from 1998 to 1999 under the new title for the spot of “Mōsō nōto” (Daydream Notes). It tells the story of the World War II German tank commander Otto Carius and his company, with fictional elements.

The 2009 manga The Wind Rises was the first story in 10 years, and hence a “comeback.” The real-life Japanese engineer Horikoshi Jirō and the Italian engineer Giovanni Battista Caproni appear, and the complete “daydream” that it represents, including a meeting between the two with no historical basis, is a point of similarity with Tigers in the Mud. After this, there were no more additions, and The Wind Rises marked the end of “Miscellaneous Notes.”

As it happens, Miyazaki’s contributions to model magazines were based on a suggestion by Ōtsuka.

Advice on Drawing Locomotives

From 1971, Ōtsuka wrote a column for Hobby Japan on tanks and other military vehicles. He had extensively researched Japan’s many such vehicles and worked as an advisor on product planning and design at the model maker Tamiya. He was even invited to participate in projects for model company Max Mokei in 1973, but the firm folded the following year. It was only natural that he introduced Miyazaki, who had similar tastes, to the editorial team at Hobby Japan.

When Model Graphix was launched in 1984, Ōtsuka was asked if he would write a regular spot, and he invited Miyazaki, promising him that he could freely follow his interests. This led to “Miyazaki Hayao’s Miscellaneous Notes.”

The film Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind was also based on a manga of the same name published from 1982 in the monthly magazine Animage. Apparently, Ōtsuka made a recommendation here too. Suzuki Toshio, now a Studio Ghibli executive and producer, was on the magazine editorial staff then, and when he tapped Ōtsuka for a series, the veteran offered the memoir Sakuga ase mamire (Animation Drenched in Sweat). After this came to an end in the February 1982 issue, it was followed by the Nausicaä manga.

Nausicaä tries to prevent war in a postapocalyptic world. (© 1984 Studio Ghibli•H)

In 2012, Miyazaki asked Ōtsuka to pay a visit to Studio Ghibli, where he was working on The Wind Rises, seeking advice on the steam locomotives that appeared in the film. When I met Ōtsuka shortly afterward, he told me he had provided detailed explanations on the Walschaerts valve gear, pointing out that his friend Miyazaki had no love for trains. “Only planes and tanks,” I remember him joking.

When Ōtsuka was a junior high school student, during World War II, he became obsessed with locomotives and often went to an engine shed in Yamaguchi Prefecture to draw huge numbers of accurate sketches. Through getting to know the engineers, he was shown everything from how the engines were operated to the drive systems. From these visits, he unconsciously developed an animator’s grounding in realistically drawing vehicles based on how they actually worked. Having learned these basics from a young age, Ōtsuka explained such technical matters logically, analytically, and lucidly, nurturing many talented younger filmmakers.

In The Wind Rises, Jirō travels to Nagoya on a Class 9600 steam locomotive, which was Ōtsuka’s favorite. He could be said to have returned to his roots in the lecture he gave on drawing locomotives at Ghibli.

Ōtsuka in September 2018 with a half-built model of the Fiat 500 that hero Lupin drives in The Castle of Cagliostro. His own love for the vehicle inspired its use in the film. (Photograph by Kanō Seiji)

“You Must Live,” But How?

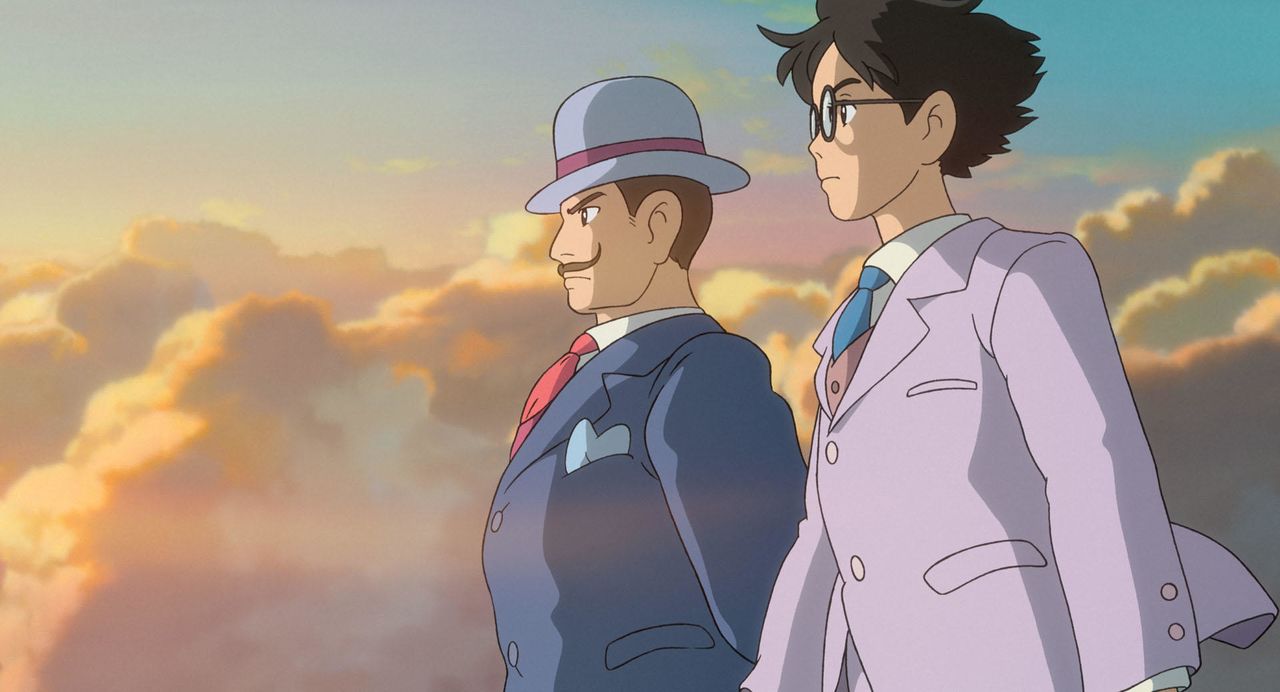

In the final scene of The Wind Rises, the protagonist Horikoshi Jirō faces Japan’s defeat and the piles of wrecked fighter planes that he designed. His beloved wife Naoko appears, telling him, “You must live,” before fading away. Then his mentor Caproni says to him, “You must live. But now, shall we drop by my house? I have some very excellent wine.”

Horikoshi Jirō (right) with Giovanni Battista Caproni. (© 2013 Studio Ghibli•NDHDMTK)

For the final scene, where they disappear among the grass, the animation was overseen by Futaki Makiko, who died a few years after the film’s release.

In May 2016, I interviewed Yasuda Michiyo for the last time. She told me that the previous day Miyazaki had called her to say that production was not going well for his short film Boro the Caterpillar, ultimately released in 2018. When Yasuda suggested he had better make another feature film, he immediately invited her to work on it with him.

An old friend of Miyazaki’s since Tōei Animation days, Yasuda had withdrawn from the frontline of filmmaking after Ponyo (2008), but worked as color designer on The Wind Rises, at the director’s behest. Apparently, Yasuda had responded to Miyazaki’s 2018 invitation by saying he should find someone younger to work with. Five months later, she passed away. It was the next month that reports emerged that Miyazaki might make another feature film.

Whether coincidentally or inevitably, the last scene of The Wind Rises seems to have predicted Miyazaki’s eight years of creative activity since.

Imagining Horikoshi as representing Miyazaki, Caproni stands for the many mentors and more experienced people who have helped him. These include Mori Yasuji from Tōei Animation, Ōtsuka, and possibly Takahata Isao.

The Wind Rises finishes with the message that even at the end of a decade of creativity, when the country has gone to ruin and loved ones have died, “You must live.” The title of the film comes from a novel by Hori Tatsuo, which itself is based on a quotation from a poem by Paul Valéry, “Le vent se lève! . . . Il faut tenter de vivre!” (The wind is rising! . . . We must try to live!) But what is the way to live?

As its title suggests, the film How Do You Live? is set to depict the struggles involved in searching for an answer to this question. For us today who face repeated disasters and an unprecedented pandemic, the matter has become all the more urgent. I look forward to the completion of this film.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Miyazaki Hayao (left) with Ōtsuka Yasuo at A Production, around 1971. Photo by Minami Masatoki. Courtesy Ōtsuka Yasuo’s family.)

anime Studio Ghibli Miyazaki Hayao The Wind Rises Ōtsuka Yasuo