Remembering Kaji Maki, the “Father of Sūdoku”

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Together in High School and Beyond

On August 10 this year, Kaji Maki passed away due to cancer. He had been the founder and talented editor of the puzzle magazine Nikoli for many years, and his death touched off an outpouring of heartfelt messages of condolences and sorrow from all around the world.

The reason for his global following was simple: He was the “father of Sūdoku.” This number puzzle, which first appeared in a US magazine in 1984 as “Number Place,” captured his attention, and he gave it the new name, a contraction from the phrase sūji wa dokushin ni kagiru, “numerals must be single.” The game would remain relatively unnoticed for more than two decades, though, until 2005, when it suddenly broke out as a major hit in Britain. From there the Sūdoku boom spread worldwide.

Gotō Yoshibumi was a classmate to Kaji in high school. In 1999 he entered the game- and puzzle-focused firm Nikoli, which published a puzzle magazine of the same name; today he heads the Japan Sūdoku Association. Having known Kaji since a half-century ago, he has this to say about him:

“He was an enormously attractive character, and he was a popular figure wherever he went. He tended to act on spur-of-the-moment inspiration, though, making him a difficult person to pin down and define precisely. It might be better to say he was a person to whom ordinary definitions didn’t apply.” [Laughs]

Gotō Yoshibumi, chair of the Japan Sūdoku Association. (© Nippon.com)

In 1980, when Kaji decided to launch Nikoli, Japan’s first puzzle magazine, Gotō tried to dissuade him from what he believed would be a fruitless endeavor. But it was this magazine that would plant the seeds for the global Sūdoku boom in later years.

Getting Game Fans Involved

As noted above, Kaji came up with the name Sūdoku, but he did not invent the game. It was an American architect and puzzle fan, Howard Garns, who created Number Place—a game with rules identical to those of Sūdoku—and gave it that name.

“I had the chance to do some of Howard’s puzzles, but I soon tired of them,” says Gotō. “They were so easy as to be boring. Howard produced about a dozen of the puzzles for a games magazine and then left them behind. When Kaji-san learned about Number Place, he introduced it in his magazine, but his genius was in the way he asked readers to submit their own puzzles for publication.”

Kaji may have launched a games magazine, but he was not himself deeply into the puzzle world. He would go on to serve as editor in chief of Nikoli for 11 years in all, but he was never involved on the puzzle production side. Indeed, much of his work there appeared to involve writing essays about things that captured his fancy. Much of his life seemed to be a celebration of the pursuit of pleasure—drinking from the afternoon, playing mah-jongg, betting on the horses.

But Sūdoku needed little attention from its distracted father. While Kaji enjoyed his days, the puzzle he had named gradually took on a life of its own. Nikoli was a most unusual magazine for its degree of reader participation. Most of the puzzles it printed had come in the first place from readers, who had received modest payments for their submissions.

Japan’s puzzle fans flocked to the magazine and its approach, quickly becoming Sūdoku fans and submitting a steady stream of problems for publication. Some of the most talented puzzle creators were snapped up by Nikoli as employees. Over time, the game Sūdoku took on a life of its own, propelling its host magazine to new heights as it continued to advance.

The Puzzle Takes Off

Toward the end of the last century, as Sūdoku was beginning to stake out its territory as one of Japan’s most popular puzzles, Gotō joined the Nikoli team. In 1999, as a fresh entrant, he told Kaji: “If you want to make this company really grow, we’ve got to take it worldwide.”

As Gotō recalls, Kaji had an almost legendary lack of interest in sales and marketing. He did have an interest in foreign countries, though, and he appeared to be interested in the idea of giving his operation a more global scope. Gotō put his overseas experience to work and the two of them began marketing the wide variety of puzzles carried in Nikoli to media publishers abroad.

They saw little success for some time, but at last, in late 2004, they heard that Sūdoku was gaining popularity among readers in London. They looked into the situation and found that the Times of London had placed a puzzle in its November 12 edition that year, touching off something of a boom.

Gotō was surprised to learn the name of the person who had sold the Sūdoku game to the Times: Wayne Gould. A puzzle fan from New Zealand, Gould had gotten hooked on Sūdoku after picking up a volume of puzzles in a bookstore during a 1997 visit to Japan, and had gone on to write a software program that would automatically create puzzles. He was known to Gotō and Kaji, having contacted them in the past to pay his respects to the company that had developed the game. And now that he had succeeded in selling it to the Times of London, the Sūdoku boom was on.

Wanting to see what was happening in Britain with their own eyes, Kaji and Gotō headed to London. There they found that the Sūdoku boom was beyond anything they had imagined. Gotō recalls: “Just about every newspaper in the country, local and national alike, carried the puzzles. ‘Did you solve the Sūdoku this morning?’ had even become a common greeting during people’s morning commutes. At the time I was told that Sūdoku was one of the biggest topics of conversation, outside of the royal family, for people tired of discussing more serious news.”

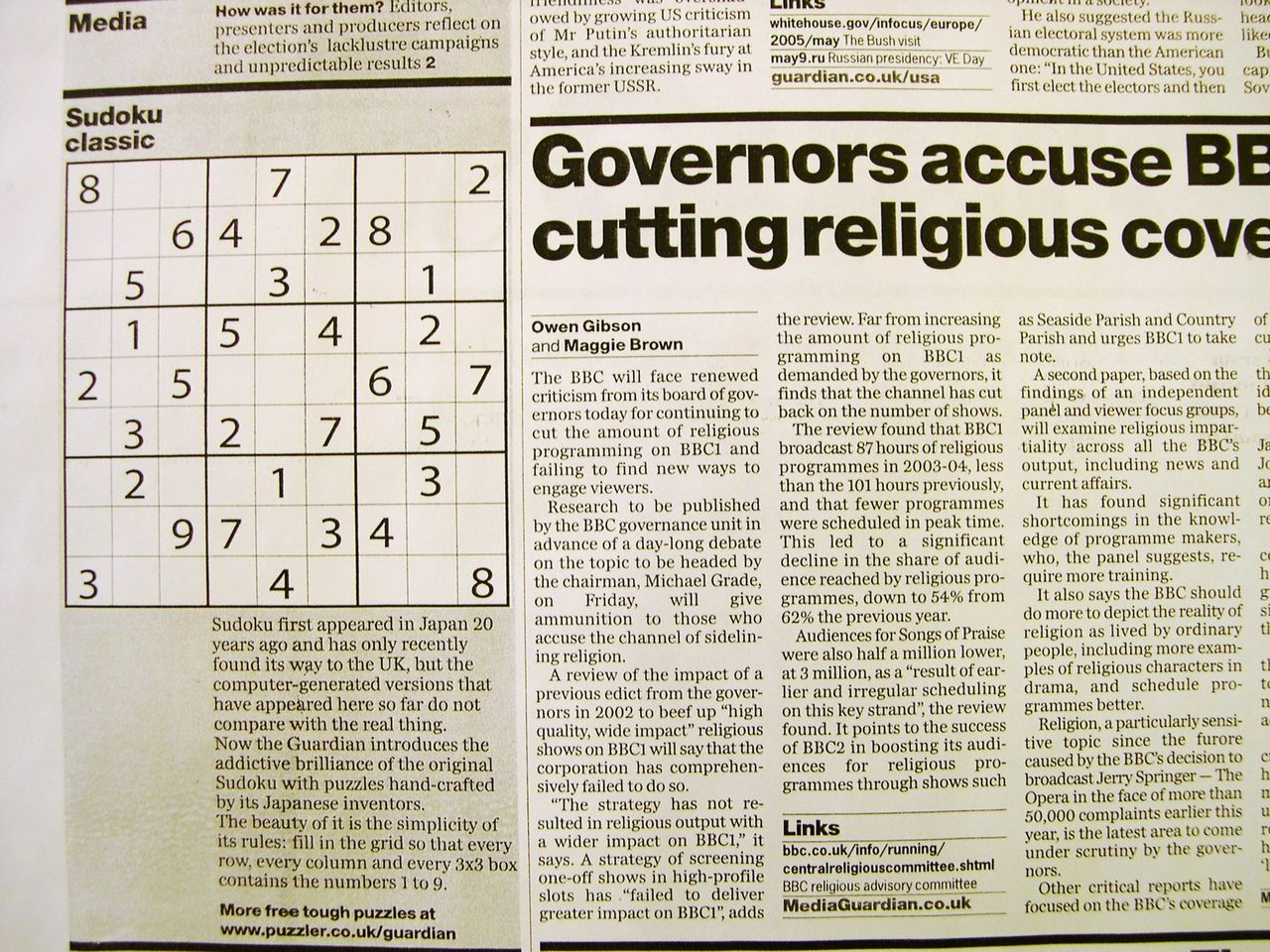

A Sūdoku puzzle appears in the May 9, 2005, Guardian. (© Jiji)

A Failed Trademark Attempt

Having experienced the UK Sūdoku boom for themselves at the end of 2004, the two returned to Britain in the spring of the following year with a goal in mind. “We’d already secured a trademark for the name Sūdoku in Japan,” says Gotō, “but we hadn’t taken similar steps anywhere overseas. We thought that if we could get a British trademark for the puzzle it could be quite profitable for us.”

It was not to be, though. The name had taken on a life of its own, gaining such broad social recognition that it was judged to be a common noun by that point. “We figured it was too late, and we gave up on the trademark. Lots of people told us that we’d really missed out by not lining up those rights in advance. But if you think about it, if we had held the Sūdoku trademark, we’d have been required to keep constant watch for imitator games arriving on the market, and likely snowed under by lawsuit paperwork. This isn’t the sort of task that a company like Nikoli, with only around twenty people on staff, could handle. I’m sure Kaji-san was just grinning and bearing it to a certain extent, but he said that in the end, it was best that as many people as possible were getting to enjoy Sūdoku.”

If this was Kaji’s goal, there was no better place for his puzzle to take off than London. Just as songs that climb the UK hit charts are likely to make a global splash thanks to the reach of the Anglophone cultural sphere, Sūdoku built on its rise as a London craze to spread to the United States, India, Australia, South Africa, and Hong Kong, and eventually to continental Europe and the Mideast as well.

Worldwide Welcomes

Kaji began touring these places, making appearances at Sūdoku events and competitions. Wherever he went, the “father of Sūdoku” received rapturous welcomes.

Says Gotō: “Kaji-san was always embarrassed to be hailed as the inventor of the game at these events. ‘No, I just found it and gave it a new name,’ he was constantly explaining. But he traveled to as many places as possible and fielded a ridiculous number of press interviews. In Spain, he once did a full day of interviews, 20 minutes per media organization, without a break. When he walked along the street he would be recognized, stopped, and asked for an autograph or a handshake. On one trip, when we were unwinding over a drink in a bar one evening, we met a man who grumbled, half-jokingly, that his wife was so into Sūdoku she didn’t have time for him any more.

“When that boom took off, we told ourselves that we had to travel all over the world while people were willing to invite us to their countries—that it wouldn’t last. But the boom seemed to go on and on, and the puzzles Nikoli made sold very well in places as far-flung as the United States, Britain, and Turkey.”

Japan was no exception when it came to the explosive popularity of Sūdoku. Kaji himself once received a message of thanks from the editor in chief of a monthly magazine that commonly sent out questionnaires to be filled in by readers, but never had much success in gaining meaningful data from them until it included a Sūdoku puzzle on the reply sheet, prompting enough puzzle fans to send in their replies that the magazine reportedly saved several million yen compared to what it would ordinarily spend to canvass reader views. Several newspapers also reported fielding complaints from readers when some newsworthy event caused urgent coverage to replace the day’s Sūdoku problem.

A Singularly Popular Puzzle-Man

As noted above, Kaji was always first to point out that he was not Sūdoku’s creator, but merely the man who had given it its most popular name. An easily-solved puzzle in an American magazine caught his eye, and he gave it a unique moniker, placing it in a magazine that was almost an accounting afterthought at his company. And once that magazine’s puzzle-fan readers latched onto it, it grew into something much more.

Gotō, who was able to tour the world with Kaji thanks to this serendipity, says he gained priceless memories from it all.

Kaji Maki in the last year of his life. (Courtesy Gotō Yoshibumi)

“There was just something about Kaji-san that drew people to him. He could entertain anyone who was with him. After the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, he heard about elderly evacuees passing their time in emergency shelters by solving Sūdoku puzzles, and he dragged me off on a trip to visit some of them. Of course he immediately made friends with everyone he met. He had the sort of charisma that could bring camaraderie wherever he went—some sort of star power that made all people love him right off the bat. That’s the kind of man Kaji-san was.”

No matter how minor the event that might have brought him together with other people, Kaji enjoyed his time together with them to the fullest. It may have been this quality that made him so popular in person—and that made his Sūdoku such a massive boom reaching all age groups and all corners of the world.

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: Kaji Maki at the first Brazilian national Sūdoku tournament, held in São Paulo on September 29, 2012. © AFP/Jiji.)