Okuda Hiroko: The Casio Employee Behind the “Sleng Teng” Riddim that Revolutionized Reggae

Culture Music Technology- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Casiotone Preset that Kickstarted Jamaican Dancehall

“Under Mi Sleng Teng,” by Jamaican singer Wayne Smith, is one of the milestones in the history of Jamaican popular music. Written by Smith and his friend Noel Davey, the pioneering dancehall classic was made using a Casio electronic keyboard. The song immediately became a smash hit when it was released in 1985, and its optimistic digital sound and addictive beat soon took the world by storm.

The rhythm section has always formed the backbone of reggae music. In modern styles, the drums and bass provide the distinctive “riddims” or backing over which a DJ or singer overdubs a vocal. It is common for numerous artists to make their own “versions” (vocal interpretations) of popular riddims, building original songs around the same basic rhythmical pattern. The “Sleng Teng” riddim, named after the song in which it was first used, has now inspired as many as 450 different songs. The riddim played a key role in bringing Jamaican music into the digital era, and is known as one of the “monster riddims” that ushered in the golden age of the dancehall era.

Today, 35 years after the original song was released, the conventional version of reggae history holds that the “father” of the riddim was Wayne Smith and his producer at the Jammy’s label in Jamaica. In fact, the history of the riddim goes back further than Smith and his collaborators. It was originally a preset rhythm pattern programmed into the Casiotone MT-40, released in 1981. It was this preset that Smith and his friends used as the basic building block for their revolutionary song.

The Casiotone MT-40, which sold for ¥35,000. (Courtesy Okuda Hiroko)

In other words, Casio, familiar to millions as the maker of the calculators used in classrooms and offices around the world, played midwife to Jamaican digital dancehall. Even more remarkably, the preset track that became the Sleng Teng riddim was the work of a young developer who was still in her first year with the company.

For years, her story has been the stuff of legend among afficionados of Jamaican music. But little has been known of Okuda’s background, and her face has never appeared in media interviews. Now, 40 years on from the original release of the MT-40, Okuda Hiroko has finally cast aside her veil of secrecy and consented to an interview.

Okuda Hiroko plays a Casio electric piano.

Straight out of Music College

During the 1970s, Casio was one of the leading players in the “calculator wars” that saw manufacturers compete for supremacy in the market for desktop calculators. The company’s innovations included the world’s first personal calculator (the Casio Mini in 1972) and the world’s first business–card-sized calculator (the Casio Mini Card, in 1978). Then, at the beginning of the 1980s, it branched out into the musical instruments business, launching an electric keyboard with an inbuilt speaker (the Casiotone 201) in January 1980.

Okuda joined the company three months later, as a new hire straight out of music college. As soon as she completed her initial training, she was set to work on preset backing tracks for the MT-40.

A Casiotone 201 on display in the showroom at Casio head office. The company’s first electronic instrument could reproduce the sounds of 29 different musical instruments.

Casio wanted to develop instruments that would be capable of providing an automated accompaniment to musical performances. As a stop-gap measure, the company decided to release mini-keyboards programed with preset rhythm tracks as a steppingstone toward this target. “In the development department at that time, there were just four of us from a musical background, all of us new hires straight out of college,” Okuda remembers. “And everyone else had studied classical music. I was the only one who knew anything about popular styles.”

In those days the environment for creating digital music was nothing like as advanced as it has become today. The MIDI standard format did not yet exist. It was necessary to convert a musical score into code, record the code onto an ROM, and then inset the memory into a specialized machine. Only then could you listen to the rhythm pattern you had written. It was a laborious, time-consuming process that meant long hours of trial and error before a pattern could be completed, and this made it difficult to commission outside developers to do the work.

For this interview, Okuda met us at Casio head office in Shibuya, but normally she works out of the company’s R&D Center in Hamura on the outskirts of greater Tokyo.

The Reggae-Mad Music Student Who Became One of Casio’s First Music Developers

Okuda had played piano since childhood. In middle school, she discovered British rock, then in its pomp, and went on to fall in love with reggae music. “Reggae is generally agreed to lie at the roots of hip-hop and rap and other styles of DJ music. The music also had a huge influence on British rock. The lyrics had a strong social and political message, but they were performed in this light, breezy style. I think that contrast was what attracted me to the music.”

After graduating from a musical high school, Okuda went on to study at Kunitachi College of Music. She had no ambitions to become a performer herself, instead specializing in general music studies, studying music history and sociology alongside theory and the harmony that forms the foundations of all musical composition. But the real focus of her studies was reggae.

This made Okuda something of a rarity in Japanese music colleges at the time, where almost all students specialized in classical music. “Even my graduation thesis was on reggae. There was no one on the faculty with the background to advise my thesis, so in the end they got a specialist in baroque music to read it. The professor read it through and said, ‘Well, it seems to be put together well enough.’ And that was enough to allow me to graduate!”

In 1979, while Okuda was working on finishing up her thesis and listening obsessively to reggae music, Bob Marley made his only trip to Japan. Okuda went to see several performances. Soon after the concerts, her eye was caught by an advertisement posted on campus by Casio, which was looking to hire graduates from music colleges for the first time. “I remember the wording on the ad: ‘Developers wanted.’ I thought, that sounds interesting . . .” At the interview, she was given a demonstration of the new Casio keyboards, which had not yet gone on sale, and was impressed by how well they were made and the potential of electric instruments. But the decisive thing that swayed her in her choice of career was the company’s global vision.

The musical instruments department was headed by Kashio Toshio, second oldest of the four Kashio brothers who founded the company. Known as the inventor of the world’s first compact digital calculator, Toshio also had a deep interest in developing musical instruments, and was driven by the ambition of “bringing the pleasure of playing a musical instrument to everyone.”

Having majored in music, and with a love of Western styles and a strong interest in developing musical instruments, Okuda was convinced that the job was a perfect match.

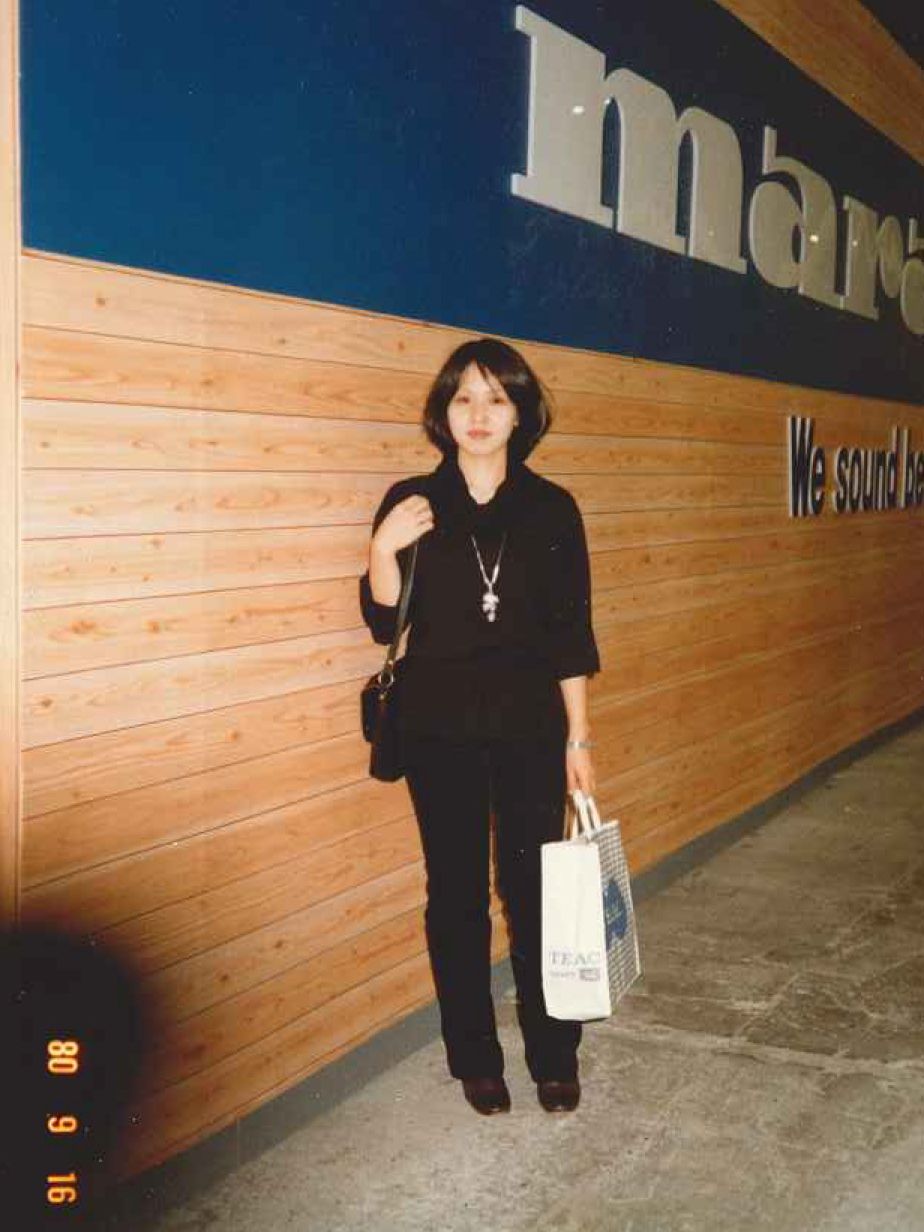

Okuda during her first six months at Casio, just before she started work on developing tracks for the MT-40. (Courtesy Okuda Hiroko)

From Preset Rhythm to Dancehall Riddim

Soon after joining Casio, Okuda was set to work on samples for use as preset backing tracks on the company’s new keyboards. She worked on creating rhythm patterns for six different genres of music, including “rock,” “pop,” and “samba” styles, and bass lines for each style that would fit with three basic chord types (major, minor, and seventh chords), as well two additional fill-in patterns to be used at the end of verses and other pivotal moments in songs.

What became the Sleng Teng riddim was originally intended as a “rock” rhythm. Why did this rock beat become so popular with Jamaican musicians? Okuda says: “In those days, my head was full of reggae. Even when I was trying to come up with a rock beat, I think it just naturally came out as something that would work in reggae as well.”

There were all kinds of constraints in terms of the types of sounds and number of notes that could be used. The preset patterns could only use drum and bass sounds, and they were limited to a length of two bars. These limitations meant programmers could not add much variety to the drum sound, and the main focus became the construction of the bass line.

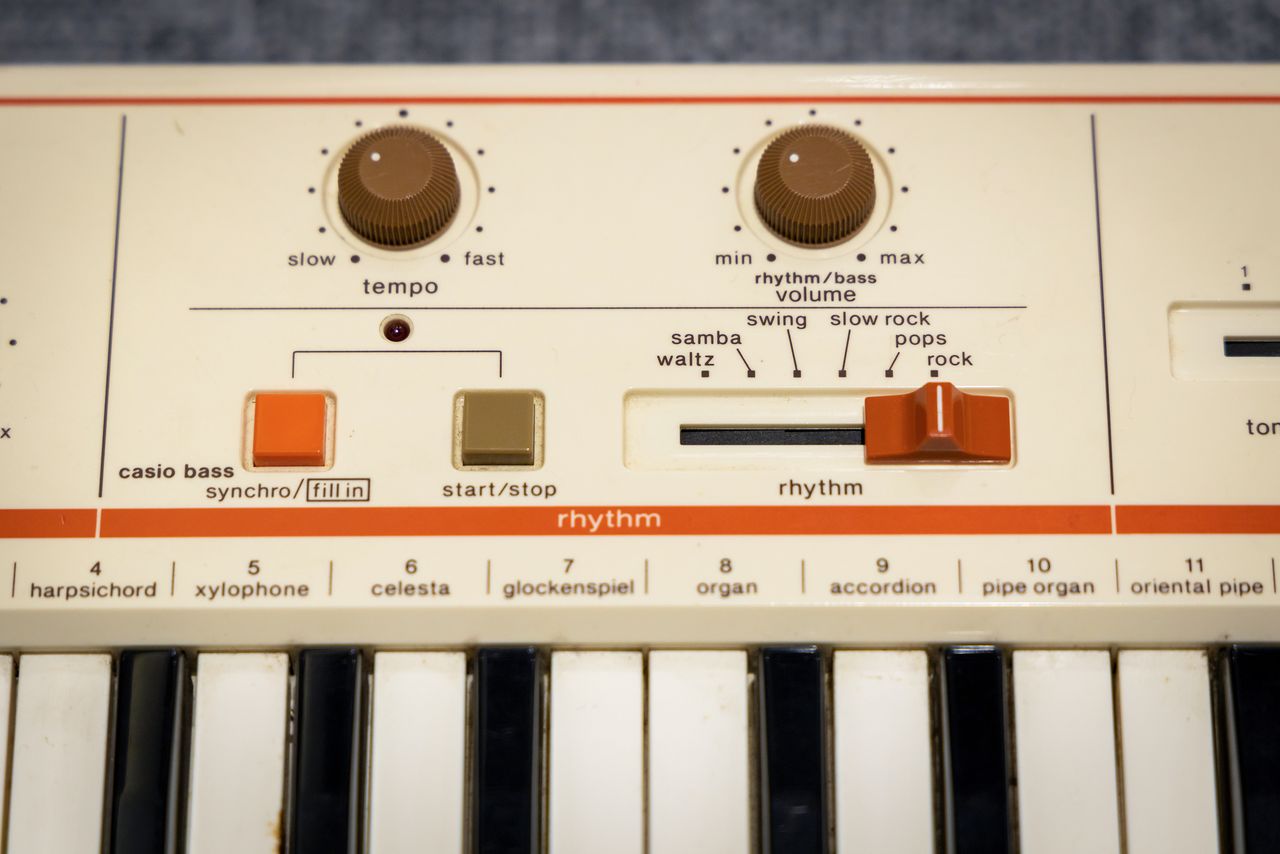

The preset buttons on the Casiotone MT-40. The number of switches was limited, which made selecting and using the presets less than straightforward. Noel Davey remembered having “lost the rhythm” at one stage during the songwriting process.

Among music fans, there is a widespread belief that the Sleng Teng bassline was derived from Eddie Cochran’s “Something Else” or a song by the Sex Pistols, but Okuda denies having had any particular recording in mind. “I did use to listen to a lot of British rock, so I’m sure there must have been songs that influenced me. But really, the bassline was something I came up with myself. It wasn’t based on any other tune.”

Okuda says she did not have reggae in mind particularly when she came up with the bassline, though she admits that she did try to create a sample that would be easy to “toast” over. In Jamaican music, “toasting” is the practice of dubbing a vocal line over a recorded rhythm track—something that has had a decisive influence on the development of rap and DJ styles. Okuda remembers that she tried not to overcomplicate the bassline by adding too many notes, and suggests that this simplicity made it easy for musicians to develop their own arrangements, as well as making it suited to the characteristic off-beat chords of reggae-influenced styles of music.

A Belated Discovery

Casio’s new musical instrument business got off to a flying start. The new keyboards were released and sold well around the world. Okuda found herself working on multiple development projects at once, and started to lose touch with the latest developments in Jamaican music. Although she heard from the sales department that the MT-40 was selling well in Central and South American markets, she says it never occurred to her to think that this might have anything to do with Jamaica.

It was when she read the August 1986 edition of Japan’s Music Magazine that she came across an article with the title “The Sleng Teng Flood,” describing how the Casiotone preset rhythm was inspiring a slew of new songs. As she read on, and saw the preset described in the piece, Okuda learned for the first time that the “rock” bassline she had written for the Casiotone keyboard had become a sensation around the world.

She immediately went out and bought a copy of the album Under Mi Sleng Teng. “There it was, loud and clear: It was definitely the preset rhythm part from the Casiotone. I’d sort of been prepared for it, but even so, I was surprised to find that the intro to the song even used the fill-in preset we’d programmed into the keyboards.” At the same time, she says it somehow made sense.

“At the time I came up with the part, I was listening to reggae all the time, and had even written my graduation thesis on the music. And now people in Jamaica, where the music was a part of people’s daily lives, had discovered my rhythm and taken it on board as part of their music. It had happened because Casio was an export-oriented company that had started to develop musical instruments, and had been bold enough to give a new employee like me, straight out of college, the responsibility for coming up with these parts. In that sense, it wasn’t a total accident. In a way, it felt almost inevitable.”

Okuda at work at Casio’s Hamura R&D Center around the time she learned of the Sleng Teng craze her preset rhythm had inspired. (Courtesy of Okuda Hiroko)

Although her rhythm had created a sensation around the world, this news did not change Okuda’s daily life at Casio. The company’s mainstream business continued to be electronic calculators. Next to that, the musical instruments business was a sideline. And although an employee might win praise for inventing a patent-winning new technology, inspiring a digital revolution in music and helping to create a new cultural phenomenon was not considered noteworthy within the company. And Okuda herself was too busy, immersed in her work on new products, to have much time to think about such things. If she occasionally saw a mention of the Sleng Teng craze in a magazine article, she might feel a secret flush of pride at her own contribution, but that was all.

Some people thought that Okuda and Casio should sue for infringement of their copyright. But the company believed it was more important for people to use the keyboards in their music and create a reputation for the Casiotone keyboards around the world. Okuda wanted people to use the Casiotone to create music and hoped the keyboards would make it easier for people around the world to make their own recordings. Even today, musicians and record company representatives sometimes discover that the Sleng Teng riddim was originally an MT-40 preset and contact Casio for permission to use the file. The reply is always that the preset bassline is free for anyone to use: just credit the source and acknowledge that the tune “uses a sound file taken from a Casio MT-40.”

As Okuda likes to say: “If I can give back even a little bit of what reggae has given me over the years, nothing could make me happier.”

The original “MT-40 riddim” is installed in the current model of the Casiotone Mini-keyboard SA-76, allowing users to listen to and use the classic “rock” preset pattern. (Courtesy Casio)

Letting Everyone Experience the Pleasure of Playing an Instrument

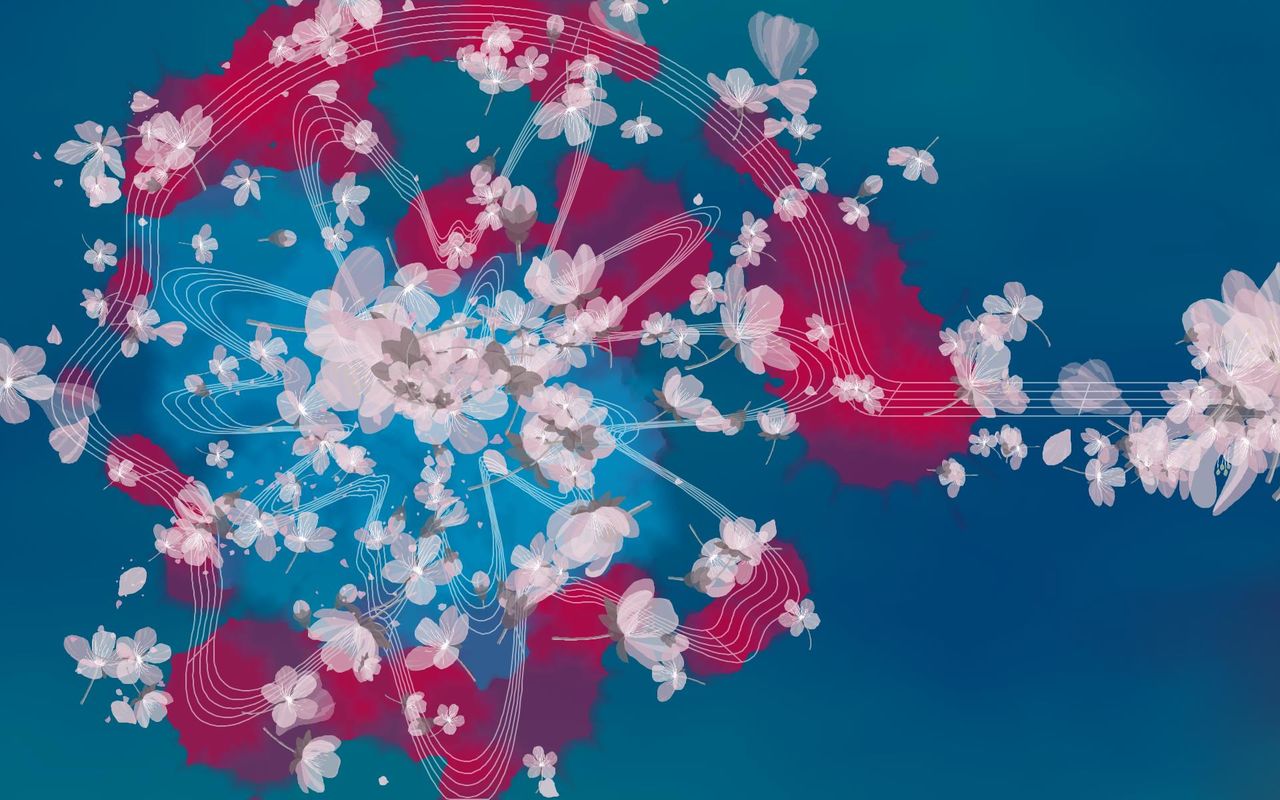

Today, Okuda is pouring her energies as a developer into a new technology called “Music Tapestry,” which analyzes a performer’s touch on the keyboard and the tone of the piece and uses this information to create a picture in real time, eventually resulting in a finished artwork at the end of the performance. Okuda says she likes the idea that even people who have never played the piano might be inspired to touch the keys and see what kind of picture results. She hopes the new technology will help more people than ever to get enjoyment from music. The philosophy of Casio’s founder still drives all her work: the dream of making it possible for everyone to experience the pleasure of playing a musical instrument.

“That the rhythm I made for the MT-40 spread around the world and is still loved today by so many people is one of the great joys of my life. It’s right up there with the happiness I felt when my children were born. In musical terms, I’ve never been able to top that first child! But there are still lots of new ways in which electronic instruments can help performers around the world, even today.”

Okuda’s work as a developer goes on, striving to provide the tools to inspire new music and further innovations in musical cultures around the world.

The artwork created at the end of a demonstration performance using the Music Tapestry technology. A wide variety of colorful creations can be seen on the official Instagram page for the new technology. (Courtesy Casio)

(Originally published in Japanese on January 3, 2022. All photos and video by Nippon.com, unless otherwise noted.)