“Spare Keys” to Organize Your Digital Possessions

Family Health Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Increasingly Unhackable Smartphones

For the last six years I have been answering questions on digital estate sent to my website. The most common questions are always the same: “I can’t get into my late father’s smartphone. Is there some way of unlocking it?” “My husband died suddenly and there’s important work-related information on his phone. How can I access it?” “It’s been a year since my daughter’s death and I want to get into her phone. Can you help?” In all, some 70% of inquiries are from those trying to get into a deceased person’s smartphone.

This is a thorny problem. Smartphone security is significantly more stringent than that of personal computers, making attempts to gain entry without the password or passcode hopeless. An iPhone belonging to a terrorist who went on a shooting spree in California at the end of 2015 was retrieved from the location where he was shot. The FBI retrieved the phone and brought a federal court case against the manufacturer, Apple, demanding a master key to unlock the phone. In other words, even the US police authorities were unable to resolve the issue of a single smartphone on their own. That is how tough smartphone security is.

As of January 2022, only a handful of vendors offer forensic services for hacking smartphones of deceased persons without passwords, and most companies that offer services relating to digital estate do not offer mobile forensics services.

The Face ID and Passcode page in the iPhone settings menu: If “Erase Data” is selected, the contents of the phone will be deleted completely after 10 incorrect login attempts.

When I receive inquiries of the type described above, my first advice to the client is to try and find out the password by any means possible. Some people write their password on the paperwork that came with their phone, while others make their car’s keyless entry code their password. If this fails, I suggest the client checks the deceased’s cloud storage or PC to see whether they saved a backup of their cellphone data, or finds another way of identifying monetary transactions or determining whether or not the deceased had an insurance policy, as appropriate. Sometimes I refer the client to one of the few vendors that offers cellphone forensics, having informed them that the average bonus payable for a successful hack is ¥300,000.

Every year, I get more and more emails asking about digital estate. The fact that family members go to such lengths to get into cellphones and track down my website is testament to the fact that digital property is increasingly important—something that has not been matched by an improvement in digital services to cater to the needs of the families of deceased users.

Users’ Need for Caution

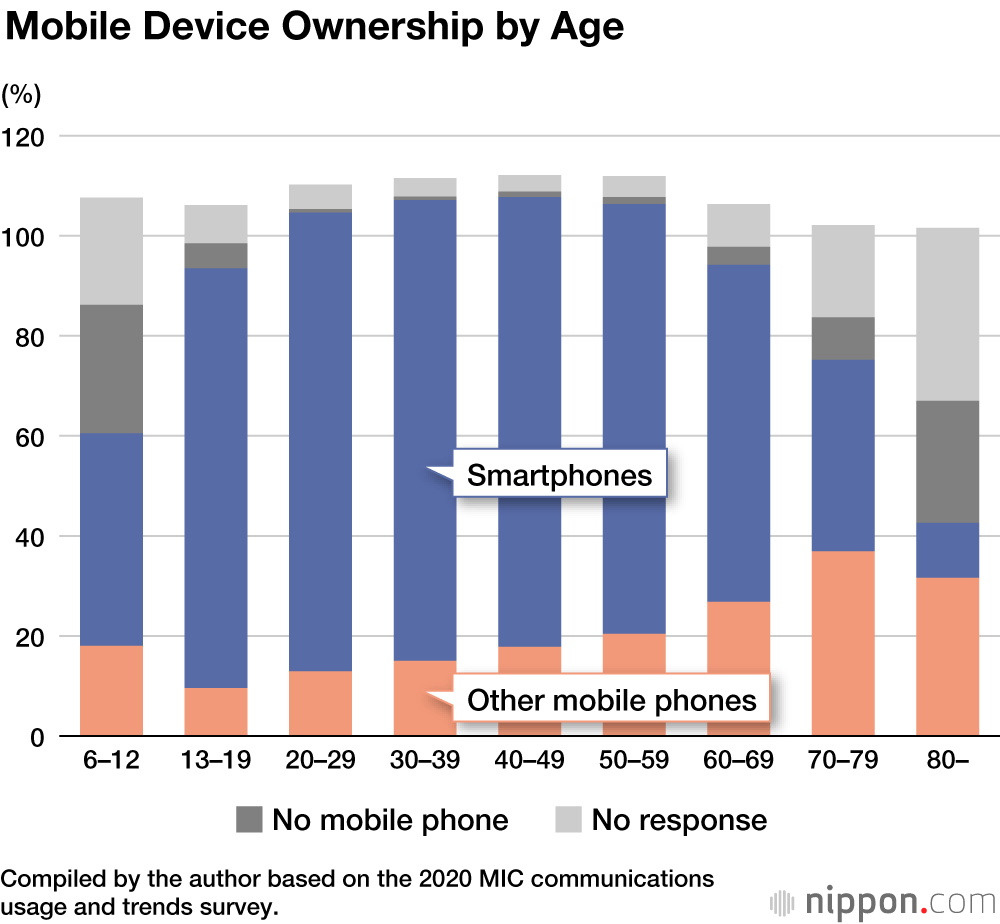

As many would surely agree, digital technology is a much bigger part of our lives now than it was 10 years ago. According to a Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) family income and expenditure survey, around 70% of households used electronic money in 2020, up from less than 40% in 2010. In the same period, according to an MIC communications usage and trends survey, the percentage of households that uses social media jumped from around 5% to over 70%. Over this same period, according to a 2021 survey conducted by the NTT Docomo Mobile Society Research Institute into mobile consumer trends, smartphone penetration jumped from less than 4% of all mobile devices to 88%—a figure that further increased to more than 92% in 2021)—while the ownership rate for more limited “feature phones” saw a marked decline.

This trend is not confined to consumers of working age. In 2020, 60.6 % of those in their sixties used social media, and the figures for those in their seventies and those in their eighties and above were 47.5 % and 46.5 %, respectively. Consumers in their sixties and seventies also prefer smartphones to other mobile devices, as per the MIC communications trends survey. While the generation gap is still there, if anything it is becoming more difficult to live without digital technologies, at any age.

Even before the establishment of the Digital Agency in September 2021, the Japanese government had been trialing technologies that would enable smartphones to function as personal and taxpayer identification devices. You get the feeling that the government is getting serious about making digital transformation a reality by 2025, the year the last of the baby boomers turns 75. In the future, digital tools will likely become essential for the purposes of official identification.

However, despite the fact that these technologies are such an essential part of our lives, these advances have not been matched by improved measures for dealing with the death of the user.

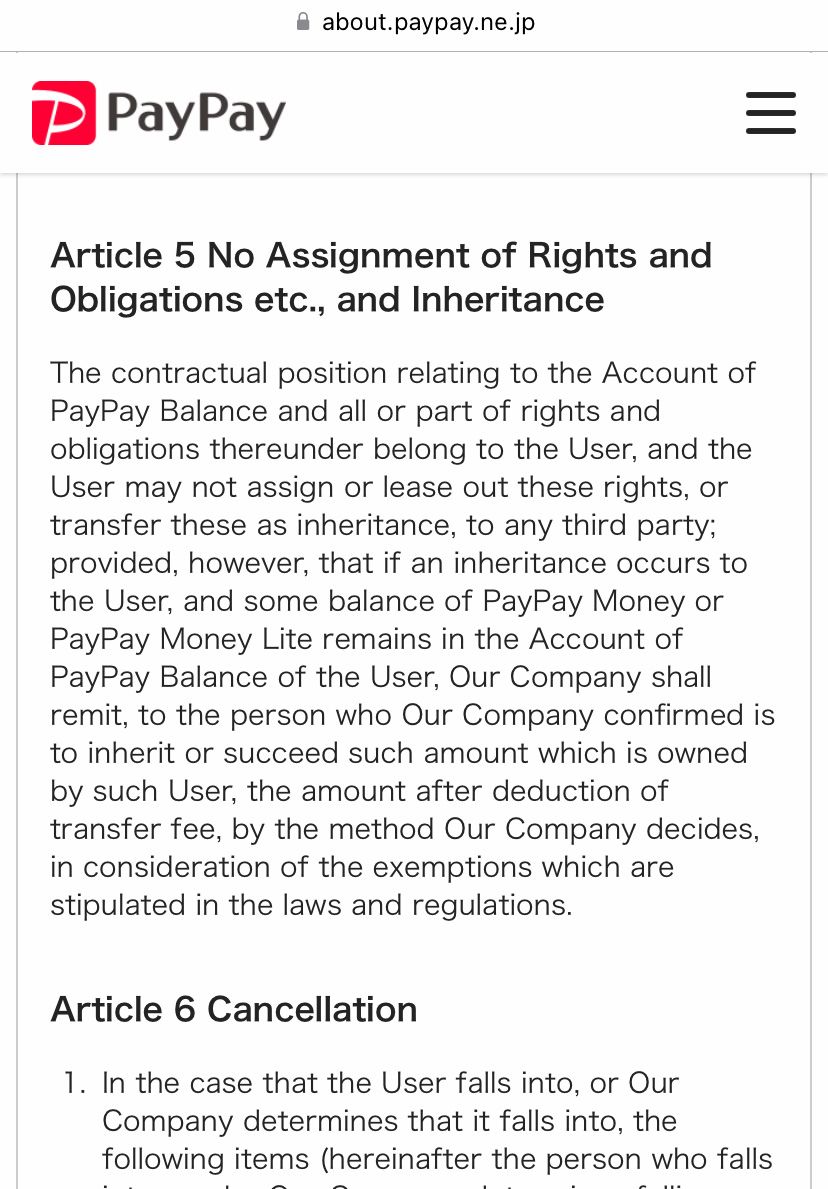

While money kept in QR code payment systems is classified as an inheritable asset, as of January 2022, hardly any QR code payment service providers had updated their FAQs to include instructions for those trying to inherit such assets. In fact, some providers’ terms of use provide no explicit information regarding what happens when an accountholder dies, while others state that all balances and rights expire upon the death of the accountholder.

Major payment platform PayPay amended its terms of use in January 2021 to make account balances inheritable assets.

Similar inconsistency surrounds the status of social media posts and blogs whose creator has died. While some services have measures in place for transferring control to the statutory inheritor, in other cases, rights to content expire upon death.

When it comes to smartphones and other digital devices, meanwhile, as noted above, there is no public support available for a bereaved family without access to the passwords to access their data. Manufacturers and communication carriers alike offer no way in principle to get at the information locked away in a deceased person’s device.

In fact, while we tend to refer to digital estate as a homogenous category, in the absence of comprehensive guidelines for handling such assets, there is presently no option but to work out how to deal with each asset type individually. After all, digital technology has only really worked its way into our lives for around 30 years. As the industry has yet to accumulate expertise on how to deal with the issues that arise, in one sense the inconsistency between service providers cannot be helped. We are in a time of flux.

Even experts in the disposition and inheritance of conventional estates are not necessarily au fait with digital estate. Ultimately, it is the family who is forced to deal with these issues, and that is the reason that I receive more and more emails on the subject every year.

To resolve this state of affairs, we must either wait for the digital industry and inheritance practitioners to start offering services for digital property, or ensure that everyone with digital assets makes preparations for the death while they are still alive. That is why I am such an advocate of putting one’s digital possessions in order.

Making a “Spare Key” for Your Phone

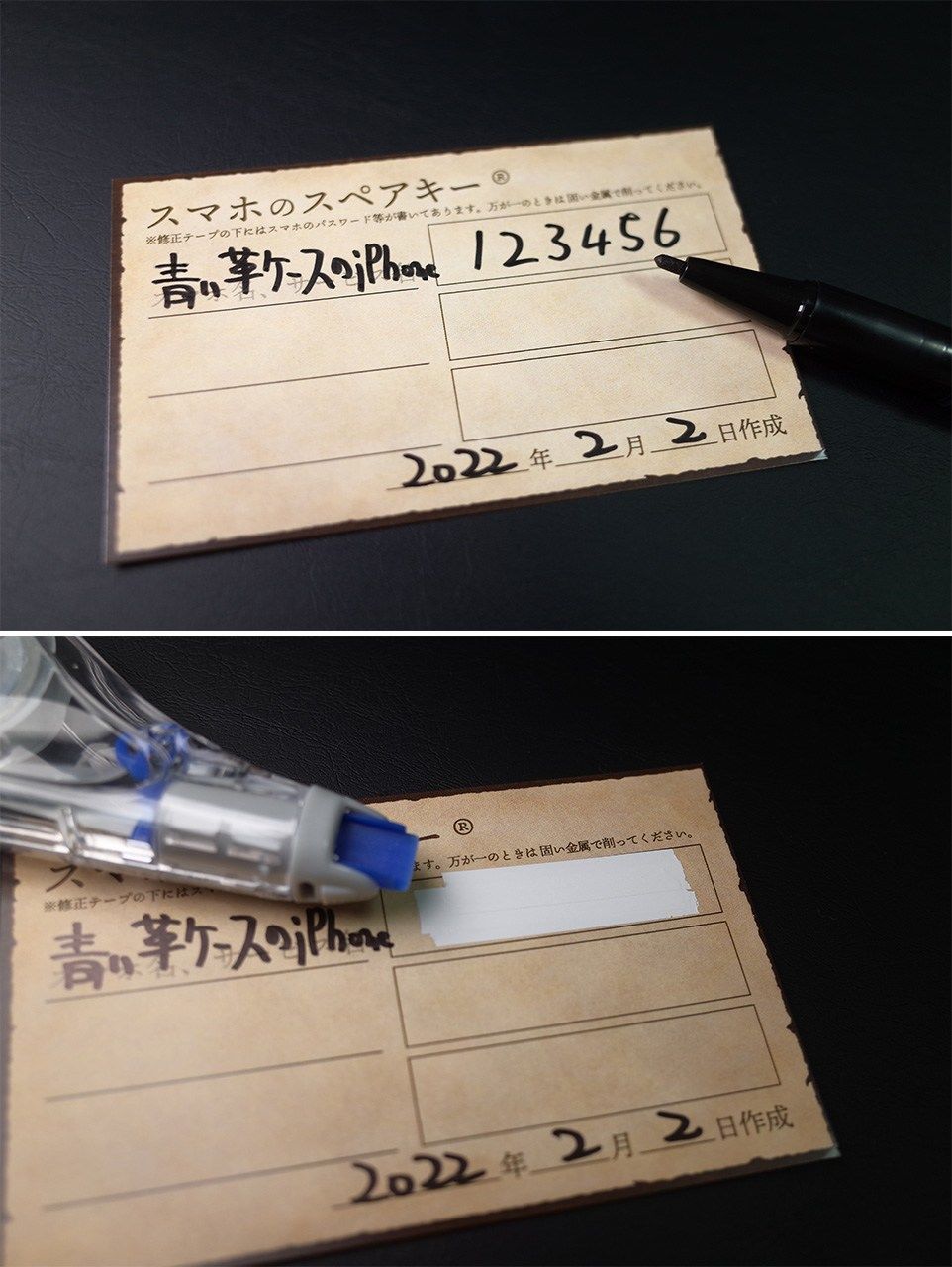

The one task to put your digital possessions in order that you must do is make a “spare key” for your smartphone.

To do this, get a piece of cardboard about the size of a business card, and write a description of your smartphone—“iPhone in blue leather case,” for instance—and your password. Next, cover the password with two or three applications of correction tape. If the password is still visible when the card is held up to the light, simply apply correction tape to the other side as well. And there you have it: a DIY scratch card.

Write a description of your phone and your password in indelible marker or ballpoint pen, cover the password with correction tape, and ensure it cannot be read even when held up to the light. Use cardboard or glossy paper to prevent the password being scratched off.

Keeping this card with your pension book, passport, or bank book makes it more likely to be discovered by your family should the unthinkable happen. By simply scratching the correction tape with a coin, your family will be able to break through the “impregnable fortress”—but increasingly one that must be breached—that is the smartphone password. At the same time, ordinarily, your password is hidden by the correction tape, so the risk of its being compromised is reduced. With a card, correction tape, and a pen, you can make one of these in less than three minutes.

If you still have some energy left after making your password card, I also recommend organizing your digital assets in preparation for your death.

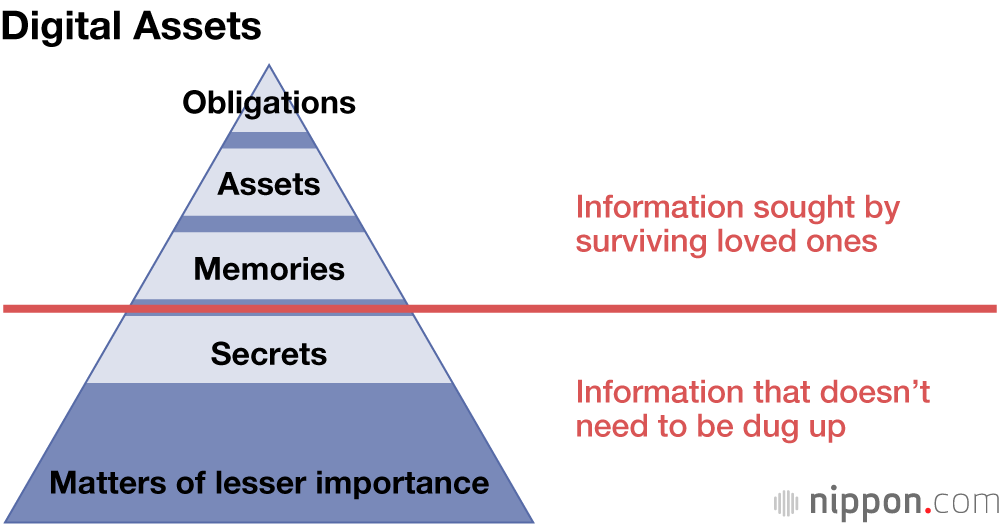

Estate falls into five main categories: obligations (the deceased’s liabilities and work in progress), assets (savings, financial instruments, and real estate), memories (family photos and mementos), secrets (information the deceased would rather not be discovered), and finally matters of lesser importance. Of these, it is the obligations, assets, and memories that your surviving loved ones generally want to find.

The situation is no different for digital estate. If you put your digital obligations, assets, and memories on your smartphone’s home screen or list them on a spreadsheet, your family will be able to find them easily should the unthinkable happen. By the same token, you should store any information you want to remain hidden somewhere completely separate. By securing this information in a place where no one looking for obligations, assets, or memories would come across it, and managing it with a separate app or protecting it with a password, you are more likely to be able to take it to the grave with you.

Note that you should include any work-related matters and secret savings in the obligations and asset categories. It is only the upper part of the pyramid that you need to prioritize.

If, in the process of organizing your possessions, you encounter an unneeded subscription, you can cancel it. This exercise is also a good opportunity for gathering scattered backups in one place. If, at the same time as organizing your affairs in preparation for your death, this exercise also makes your digital life on this earth a bit easier, then I think it is the best way you will find to order your digital possessions.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo © Pixta.)