Manga Artist Mizushima Shinji and the Fight for Gender Equality in Japanese Sports

Culture Manga People- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japan’s First Female Professional Baseballer

At the present time, there are no female players currently plying their trade in Japan’s men’s professional baseball leagues, collectively known as Nippon Professional Baseball. But while 2008 saw knuckleball pitcher Yoshida Eri become the first woman to be drafted into a men’s professional team when she signed for the now defunct Kobe 9 Cruise—and Japan has also had a women’s professional league since 2009 (the Japan Women’s Baseball League, branded until 2012 as the Girls Professional Baseball League)—if we allow ourselves a small flight of fantasy, it could be argued that Japan’s first female pro ballplayer actually arrived in the 1970s.

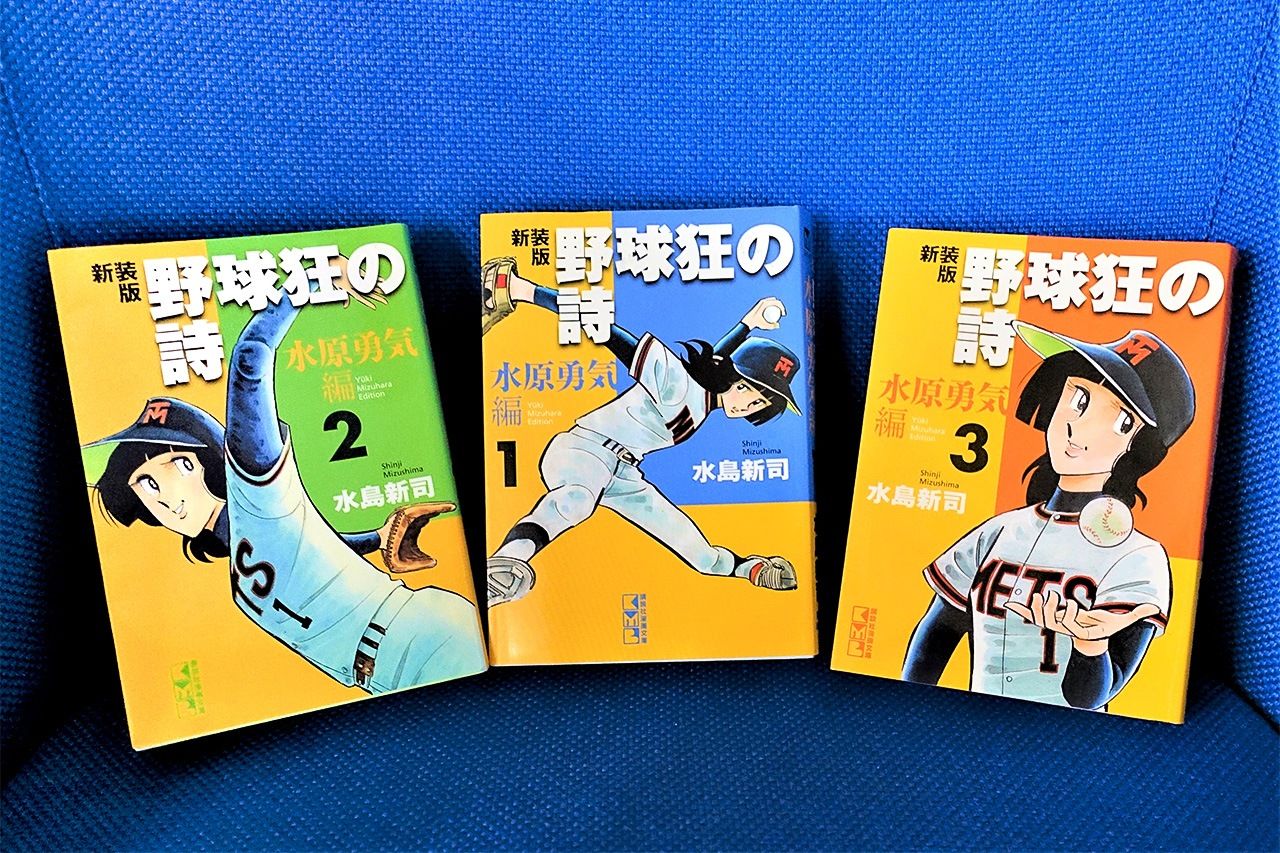

The player in question was Mizuhara Yūki, a central character in Yakyū-kyō no uta (Ballad of the Baseball Nuts), the popular 1972–76 serial by acclaimed manga artist Mizushima Shinji, who passed away on January 10 this year.

Mizuhara begins the story as a student at Tokyo’s Musashino High School, with aspirations to become a veterinarian and work with animals in Africa. But, despite having never even considered a career in baseball, she is selected in the first draft by the fictional Tokyo Mets, going on to send shockwaves throughout the baseball world and across Japanese society as a whole.

At the time, not only did NPB rules preclude the registration of players who were not biologically male, the very idea that a female player could make a valuable contribution in men’s baseball was firmly outside the realm of popular imagination. As such, the character of Mizuhara faced dual obstacles, both regulatory and conceptual.

However, the Tokyo Mets’ chief scout, along with 50-plus veteran catcher Iwata Tetsugorō and his old friend─and the team’s manager─Gori Ippei, are dazzled by Mizuhara’s pitching skills and insist on selecting her in the draft. And though she initially rejects their approach, she eventually signs a contract with the team, though not before requesting an additional clause that stipulates she must be treated exactly the same as her male colleagues.

In only her debut season she ascends to the first team, thanks to assets including a keen intelligence that stands out among her ragtag band of teammates, mound composure second only to the team’s ace pitcher Hiura Ken, and her own painstakingly practiced breaking-ball pitch, dubbed the “Dreamball.” Her performances as a relief pitcher see her competing with the finest hurlers in Japan’s Central League, including Hanshin Tigers legend Tabuchi Kōichi.

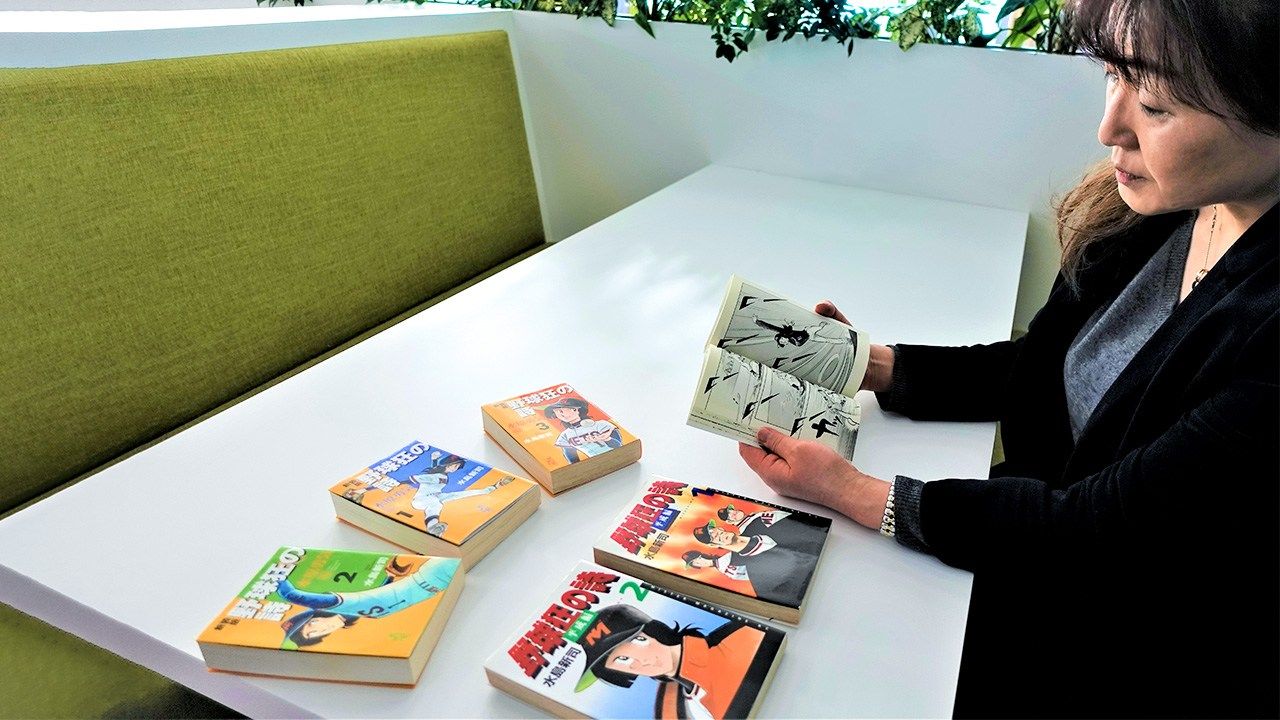

Special Mizuhara Yūki editions of Yakyū-kyō no uta. The comics provide numerous scenes that continue to resonate with contemporary gender discourse. (© Nippon.com)

A Longstanding Dedication to Realism

While creating his tales of Japan’s first female professional baller, artist Mizushima Shinji placed the utmost emphasis on crafting genuinely plausible scenarios.

Born in Niigata in 1939, from the third grade of elementary school he started taking on odd jobs for pocket money, and by the time he reached junior high he was helping out in the family fishmonger. It was after graduation from junior high school, while having to get up at five o’clock each morning for arduous shifts at a brokerage, that he began to fill whatever short breaks he could snatch by devouring manga borrowed from the local kashi-hon’ya booklender.

Already a keen drawer, he entered a contest held by the Osaka-based kashi-hon manga publisher Hinomaru Bunko, and on the recommendation of the legendary artist Saitō Takao, he finished in second place. In contrast to the majority of submissions in that era, which adopted an edgy, controversial tone, Mizushima reportedly won Saitō over with an exceptionally fully realized contribution foregrounding a sense of fun and enjoyment.

Mizushima Shinji is greeted by Emperor Akihito at an imperial garden party held in November 2015 in Tokyo’s Akasaka Imperial Gardens. In 2005 Mizushima was decorated with Japan’s Purple Ribbon Medal of Honor, followed in 2014 by the Order of the Rising Sun. (© Jiji)

That big break saw Mizushima relocate to Osaka to begin his career as a manga artist. And while he initially dabbled in historical manga and virtually every other genre besides (with the exception of shōjo manga aimed at a young female audience), it was only after honing his ability to convincingly capture the throwing, hitting, and fielding that goes into baseball that he really found his feet, subsequently resolving to focus his efforts on the baseball comics he had loved since boyhood.

His first foray into the genre that would come to define him was Otoko do ahō kōshien (“Men’s Dumbass Kōshien”), which ran in 1970–75 in the weekly comic anthology Shōnen Sunday. And the success of that series paved the way for a succession of much-loved, baseball-themed Mizushima classics, including Dokaben (1972–81) and Abu-san (1973–2014).

With the stated aims of “showing children everything about their beloved baseball,” and “drawing baseball manga free of falsehoods,” Mizushima devoted himself to learning as much as he could about the sport. He took this mission to such great lengths that when the Nankai Hawks (today the Fukuoka Softbank Hawks), then helmed by the late, great player-manager Nomura Katsuya, came to Tokyo for a match at the Kōrakuen Stadium, he even volunteered as a ball boy at their practice sessions. And eventually this dedication earned him a free pass to perform this role at any ball ground he went to.

Miracle Pitch Born from Professional Insights

And just like Mizushima’s other sporting works born from a meticulous realism, Yakyū-kyō no uta was no mere flight of fantasy. He asked numerous professional ballers what they saw as the profile of a female player who might be able to outperform men. And while most dismissed the idea, it was Nomura himself who posited the idea that a single-inning breaking ball pitcher could be in with a chance. That was the inspiration for Mizuhara Yūki and her signature weapon, the Dreamball.

The Dreamball itself was also rooted in fact, combining the shootball of Emoto Takenori, then pitching for the Hanshin Tigers, with the screwball of Clyde Wright, who would later throw for the Yomiuri Giants. And this combination of breaking, shaking, and dipping was also confirmed as plausible by Nomura.

Even for a baseball manga artist as confident of his place in the genre as Mizushima Shinji, it was a gamble to posit a world in which female players could actually compete with men on an even footing. So why did he decide to take it on?

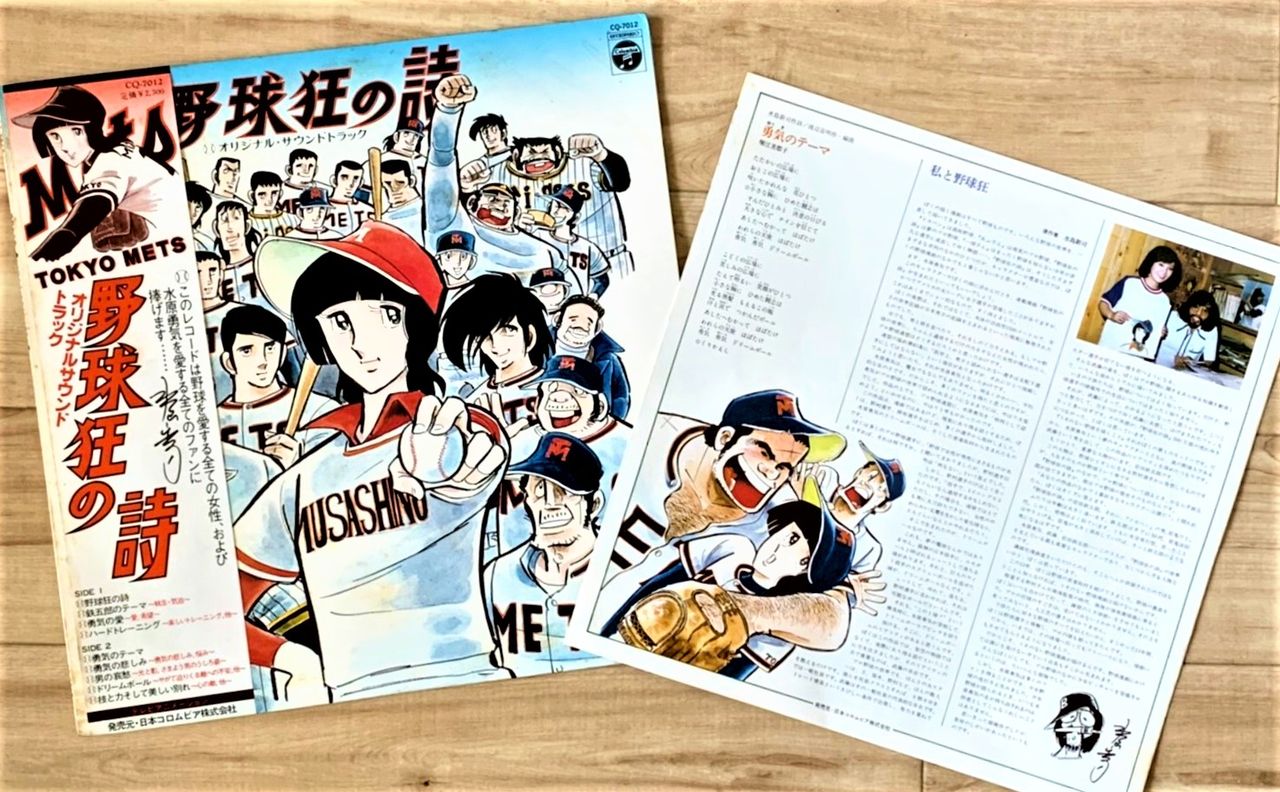

According to the sleeve notes to the 1978 soundtrack of Yakyū-kyō no uta’s anime adaptation, the inspiration came from the fact that from 1971 to 1978 the women’s 1,500-meter freestyle swimming world record was faster than the Japanese men’s record. By demonstrating to Mizushima the existence of female athletes capable of outperforming men, this record also inspired the artist’s own assault on the edifice of preconceived gender roles.

The 1978 LP release for the soundtrack to Yakyū-kyō no uta’s anime adaptation (broadcast 1977–79) bore a dedication from Mizushima Shinji “to all the girls who love baseball, and all the fans who love Mizuhara Yūki.” (Courtesy Hotta Junji)

Cometh the Hour, Cometh the Woman

Another possible factor was the longstanding tendency of Japanese audiences to gravitate toward female characters during times of economic downturn. The 1970s were beset by an ongoing energy crisis spanning the oil crises of 1973 and 1979, casting the world into lasting recession and causing shortages of many essential day-to-day products. And like clockwork, shōjo manga heroines like Oka Hiromi of Ēsu o nerae! (Aim for the Ace!, 1973–80) and Oscar François de Jarjayes of Berusaiyu no bara (The Rose of Versailles, 1972–73) won the hearts of the Japanese public.

In any age, great creatives tend to capture the collective mood of their times. Perhaps this is pure speculation, but I wonder if Mizushima wasn’t also inspired by such trends to portray a female pitcher tackling the baseball world head on.

While this neither confirms nor refutes that suspicion, Yakyū-kyō no uta did actually feature a collaboration with shōjo manga artist Satonaka Machiko. Previously, Satonaka’s name had also inspired the appellation of Satonaka Satoru, ace pitcher in Dokaben. Mizushima had reached out to Satonaka and secured permission to borrow her name, recalling later: “I wanted girls to read my work, so I was aiming for a name that might feel familiar to them.” And it is this that makes me feel that by portraying a female character, he was seeking to convey the appeal of baseball to a shōjo manga readership.

That said, creators of the stature of Mizushima Shinji are often known to go beyond simply capturing the spirit of their times, instead playing a direct role in shaping them through their work.

For example, in the April 23, 2005, edition of the weekly magazine Shūkan Gendai, Mizushima described how the eponymous hero of Abu-san was comfortable swinging a one-meter bat, a length beyond even the liking of recognized Japanese batting greats like Ochiai Hiromitsu, Kiyohara Kazuhiro, and Shinjō Tsuyoshi. Many who read this were struck by the comparison, interpreting it as a sign that Mizushima viewed his characters on the same plane as real-world athletes. And this state in which dreams—namely, art—and reality are essentially indivisible seems like the very apogee of Mizushima’s aforementioned goal of creating “falsehood-free” baseball manga.

Symbolizing this, within the narrative arc of Yakyū-kyō no uta, Mizuhara’s Dreamball pitch is actually inspired by a dream experienced by another key character, the farm-dwelling catcher Mutō Heikichi. The dream itself is no dramatic premonition, but a more prosaic vision in which Mutō ascends to the first team as Mizuhara’s catcher, and the Dreamball itself is brought to life by reverse engineering from Muto’s accounts of his dream. This capacity to unlock human potential gives dreams an almost equal significance to reality.

In 1991, the gender restrictions were finally removed from NPB regulations, while 1997 saw the formation of the Japan High School Girls Baseball Federation, and in 2008, Yoshida Eri inked her debut contract in the Kansai Independent Baseball League. At each of these historic junctures the name of Mizuhara Yūki was raised. Arguably she represented a dream that smashed preconceptions and in so doing helped bring about real-world change.

In 2008, high school knuckleball pitcher Yoshida Eri became the real-life Mizuhara Yūki when she signed for Kansai Independent Baseball League team Kobe 9 Cruise. Her subsequent transfer to US Golden Baseball League team the Chico Outlaws was reported by the New York Times. (© Kyōdō)

The aforementioned liner notes to the Yakyū-kyō no uta anime soundtrack also contain the following statement from Mizushima: “Mizuhara Yūki won a lot of fans and boosted the popularity of girls’ baseball. And as an artist, nothing makes me happier than the way that her name gets brought up whenever the topic of girls’ baseball is discussed. It was a work on which I took a major gamble, so it’s great that those labors have borne fruit.”

And even today, Mizushima Shinji’s gamble is surely being carried further, as new pioneers emerge to build on Mizuhara Yūki’s progress. I have no doubt that we will one day see a player take the mound in an NPB game and pitch the fabled Dreamball.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: After Mizuhara Yūki smashed preconceptions about baseball being an exclusively men’s sport in the 1970s, in 1997 the Yakyū-kyō no uta Heisei Edition saw her return to the front line of the sport in her forties, this time as a manager. © Nippon.com.)