A Mountain Garden of 10,000 Hydrangea: Minamizawa Ajisai Mountain

Guide to Japan Environment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Brightening the Pathway to His Parents’ Graves

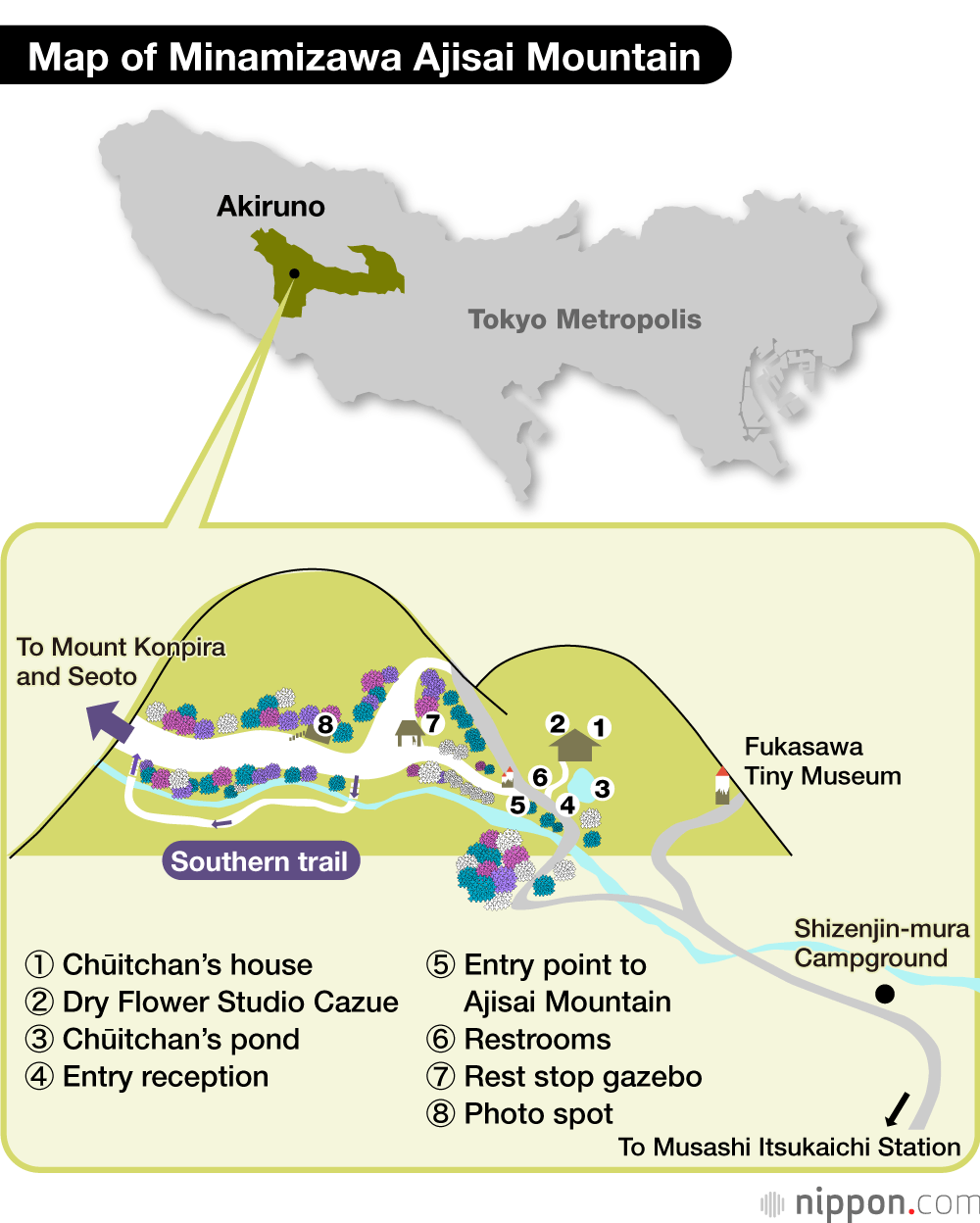

To get to Minamizawa Ajisai Mountain from central Tokyo involves a 75-minute train trip, starting with the Chūō line from the JR Shinjuku Station, with transfers to the Ōme and Itsukaichi lines, and then a 40-minute walk from Musashi Itsukaichi Station at the end of the Itsukaichi line.

An impish elf welcomes visitors to the entrance of Minamizawa Ajisai Mountain. The wood carving is the work of local sculptor Tomonaga Akimitsu. (© Amano Hisaki)

The pathway up the mountain winds its way through a breathtaking expanse of hydrangea blossoms extending along the path and down the steep slopes bordering a stream below. More than 10,000 tourists come to enjoy the sight during the peak of the hydrangea season from mid-June to early July.

Minamizawa Ajisai Mountain is owned by Minamizawa Chūichi, known affectionately by the nickname “Chūitchan,” a remarkable 92-year-old who tends to this life-long project as the seventeenth-generation head of the local Minamizawa family. Over a span of 50 years, he has worked alone to transform what was once a cedar forest into lush hydrangea shrubbery. Any journey of a thousand miles must begin with a first step. What made Chūichi take that first step?

“My ancestors’ graves are on the mountain. I just thought it would be nice if we could walk up a flower-lined path on our visits to the family graveyard.”

Born in 1930, Chūichi was the second son of a family with six boys and three girls. His father operated a lumber mill. In the postwar era of reconstruction Chūichi started his own Minamizawa Lumber Company at the age of 27.

“In this region, Obon, when the spirits of the departed are believed to visit the homes of the living, is celebrated in July. That’s when hydrangeas bloom, and so I took some saplings from two hydrangea bushes in my garden and planted them on the mountain path.”

The replanted hydrangeas bloomed beautifully. This was in June 1970, when Chūichi was 40 years old.

Chūichi and his daughter, Kazue. Since turning in his driver’s license when he turned 90, Chūichi depends on Kazue to drive him up to the mountain every day in her little truck. (© Amano Hisaki)

Learning from the Hydrangea

Chūichi began cultivating hydrangea shoots in the family vegetable garden.

“No one taught me. I learned everything directly from the flowers.”

After 10 years of trial and error, Chūichi was able to extend his hydrangea-lined path to the family graveyard.

By this time, his magnificent creation had become well-known, and more and more people came to walk the mountain path and enjoy the blossoms.

“You know, when people tell you how pretty your flowers are, you just want to plant more.”

The hydrangea path continued to grow, reaching the mountain top and beyond to include the paths leading to Mount Konpira and the Seoto hot springs, and spreading out along the slopes in between.

Blue and white hydrangea blossoms line the mountain path. (Courtesy Minamizawa Ajisai Mountain)

Hydrangeas cover the ground in a cedar forest at roughly 360 meters of elevation. (Courtesy Minamizawa Ajisai Mountain)

To ensure that his hydrangeas would get enough sunlight, Chūichi had to thin out the cedar forests and climb trees to prune their branches. He did all of this himself, while at the same time managing his lumber company, not even asking his wife Miki, who passed away six years ago, to help him.

“You can’t ask someone to do something that is not going to make any money. I got up at four every morning to work on the mountain before going to my office. Back then the company was only closed on the first and third Sundays of the month. On those days I worked on the mountain all day, getting so dirty I had to change my clothes completely three or four times. I gave my dirty clothes to the wife to launder. It exasperated her, but I’ve been told when I wasn’t around she spoke with pride of our Ajisai Mountain.”

The hydrangeas of Minamizawa Ajisai Mountain, clockwise from top left: Temari (Mophead), Anabelle, Dance Party, and Kurenai (a mountain hydrangea). (Courtesy Minamizawa Ajisai Mountain)

The Zizi Elves Show the Way

For the first three decades, Chūichi tended to Ajisai Mountain by himself. Roughly 10 years ago, however, around the time he turned 80, his brother Tsunekatsu, eight years younger and retired, started helping him out.

Another person to step up was Miyazaki Shōsaku, a retired teacher from an elementary school in central Tokyo who moved to the area to live in a house his father had purchased. Calling on local residents and his former pupils, Miyazaki formed a group of supporters called the Hana no Kai (Flower Association) and currently acts as a liaison with the local administration.

Still another person moved by Chūichi’s dedication is Tomonaga Akimitsu, who carved the wooden elves, the Zizi Forest Fairies, who act as guideposts on the route to Minamizawa Ajisai Mountain from Musashi Itsukaichi Station.

A well-known sculptor, Tomonaga created the puppets for Purinpurin Monogatari, a series broadcast by NHK from 1979 to 1982. About 35 years ago, he moved to the area and built a studio and home near Ajisai Mountain. He has since created his own museum out of a 150-year-old farmhouse, which opened in 2002 as the Fukasawa Tiny Museum.

“I got to know Chūichi when I was thinking about digging a pond and putting in koi carp. He has his own koi pond and gives me a lot of advice.”

When it was decided to set up guideposts for visitors to Ajisai Mountain, Chūichi cut down some of his own trees and gave them to Tomonaga to carve.

Located about a 15-minute walk from Ajisai Mountain, the whimsical museum opens onto a cobblestone approach. (© Amano Hisaki)

Tomonaga was born in 1944 the town of Shimanto, Kōchi Prefecture. On display in his museum are the puppets from the NHK series Purinpurin Monogatari, as well as other works of woodcraft, woodblock prints, and art. (© Amano Hisaki)

Carrying on the Dream

Even as his supporters grow in number, Chūichi has remained the mainstay of the Ajisai Mountain project.

With the approach of his ninetieth birthday, however, he began to think, “I need to find someone to take over while I am still in good health.”

And that was when two young Akiruno entrepreneurs spoke up, saying they would like to carry on in his footsteps.

Takamizu Ken and Minamishima Yūki were both born in 1990 and had been teammates on their university’s baseball team. In 2016, the two teamed up to establish Do-mo Inc., a company to develop and sell local Itsukaichi products as part of a town renewal project. One of their specialty products was Amacha.

“Amacha is a mutated species of mountain hydrangea. So we thought it would flourish on Ajisai Mountain. We asked Chūichi if we could cultivate the plant at the summit of his mountain,” says Takamizu.

Chūitchan’s Ajisai Tea was first sold in 2019. Currently, about 500 ajisai tea (Amacha) shrubs are cultivated at the top of Ajisai Mountain in a field at 460-meter elevation. (Courtesy Minamizawa Ajisai Mountain)

The two were deeply moved by their encounter with Chūichi and his life story.

“Ajisai Mountain is a local treasure and an essential tourism resource for the city of Akiruno. We didn’t know a thing about hydrangeas, but we asked him if we could get involved somehow. We wanted his guidance.”

And so Takamizu and Minamishima apprenticed themselves to Chūichi.

Chūichi had opened up the mountain to the public for free for 30 years. When he turned 70, he placed a box at the entry to the mountain and asked for a voluntary donation of ¥300 per person. For the most part, however, he paid for the whole project himself. Takamizu and his people stepped in and set up a reception counter during the hydrangea season, charging ¥500 to enter and ¥500 for parking. Their next step was to launch a crowdfunding campaign.

In 2021, Chūichi’s daughter Kazue opened her own dried flower studio Cazue above the family garage. There she makes and sells wreaths and other products out of dried hydrangea cuttings from the summer. (© Amano Hisaki)

Hanasaka Jii, the Old Man Who Makes Flowers Bloom

Maintaining Ajisai Mountain as Chūichi’s successor is no easy task.

“The most back-breaking job is pruning. It’s really difficult to decide which branches to cut and which to leave alone,” says Minamishima, who works a dizzying schedule as he also manages his company’s café outside Musashi Itsukaichi Station and its campground.

Seeing his successors’ frantic efforts annoys Chūichi somewhat.

“How can it take so long to learn which branches to cut and which to leave? There is always something that has to be done on the mountain. Plants grow quickly. The flowers and weather aren’t going to wait for you!”

The two young men listen to Chūichi’s complaints in silence.

“If it were just a matter of tending to the hydrangeas, I’m sure a professional gardener could do much better. But that’s not enough to carry on the spirit with which Chūichi started this project. We don’t know anything about hydrangeas, but I’m confident we are more determined than anyone else when it comes to valuing his feelings and making sure this place gets handed on intact to future generations,” says Minamishima.

Next to him, Chūichi smiles like a grandfather watching over his grandchildren.

“So long as my body allows, I’ll keep going up the mountain to teach them. But only the Buddha knows how long I can do that. Ah well, I’m leaving it up to these two. They are going to have to figure things out on their own.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Ajisai Mountain’s creator Minamizawa Chūichi, at center, and his successors, Takamizu Ken [left] and Minamishima Yūki. Courtesy Minamizawa Ajisai Mountain.)