Manga as a Window on Japanese Culture

Depicting the Essence of Sumō: Traditional and New Ideals in Manga “Hinomaruzumō”

Culture Anime Sports- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Sumō Origins

Young children naturally tend to jostle and wrestle with each other, something that shows how the act of wrestling itself is likely rooted in human instinct.

Children fight with their bare hands and if they roll their opponent over, they win. Throughout human history, martial arts of this kind have existed. Relics that show men wearing belts around their waists and wrestling have been excavated from Mesopotamian ruins estimated to date as far back as 3000 BCE. Even today, wrestling thrives around the world in such forms as Bökh in Mongolia, Koshti in Iran (said to have originated in the ancient Achaemenid Empire,) and Schwingen in Switzerland.

Japan’s sumō is another example. In sumō’s case, while it is a lucrative professional sporting event on the one hand, it retains traditional religious aspects that date back to ancient times.

Sumō’s origins are said to go back to the time of legend, but the first historical evidence of it appears in the early part of the seventh century. Sumō no rekishi (The History of Sumō) by Nitta Ichirō cites a historic document that describes matches being held for Japanese nobles and envoys visiting from the Korean peninsula in 642. In the seventh century, Emperor Tenmu (r. 673–686) and Empress Jitō (r. 690–697) are said to have watched sumō bouts by men who had traveled to the capital from the provinces. And in the eighth century, strong men from Japan’s various regions were summoned to compete, establishing the sport as a court event. These accounts show that there has been a strong interest in sumō since ancient times, and even today, the Japanese emperor frequently attends tournaments.

The Konjaku monogatarishū, a collection of tales thought to have been compiled in the twelfth century, contains a number of episodes related to sumō. These include a story from the time of Emperor Murakami in the tenth century of a bout between two of the strongest wrestlers in the land, a newcomer and a veteran, that had a tragic conclusion and led to such bouts becoming taboo. It also tells of a sumō wrestler who pitted his strength against a giant snake and won in impressive fashion. The modern form of sumō is said to have originated in this ancient version.

Today, there are six regular professional sumō tournaments each year. These feature bouts over 15 days, with rikishi (wrestlers) competing once a day. If a wrestler manages to be victorious in all his bouts, he is almost certain to win the tournament, but remaining undefeated is far from an easy task.

The Ryōgoku Kokugikan in Tokyo is known as the home of professional sumō. Of the six main tournaments held each year, three take place here. (© Jiji)

Victory in at least eight bouts is considered a good result as it assures a wrestler a winning record at the tournament and a chance to move up in the rankings. On the other hand, a rikishi who loses eight matches risks being demoted.

Wrestlers wear their hair in a traditional topknot known as a chonmage. Their bodies, meanwhile, are naked except for a long loincloth called a mawashi that is tightly wrapped around the waist and groin. The mawashi is an ancient form of undergarment that can be found across East and Southeast Asia. In Japan, a variant called a fundoshi was widely worn.

Fundoshi are less common today, but remain popular among a small group of enthusiasts who avidly espouse the comfort of the garment. Men clad in fundoshi can often be spotted at old festivals like the Sanja Matsuri in Tokyo’s Asakusa. Interestingly, wearing a red fundoshi was thought to ward off sharks when fishing, much like how people in the past believed the indigo blue of jeans warded off rattlesnakes.

Sumō as Seen by Jean Cocteau

The ring where wrestlers compete is called a dohyō. Setting atop this raised earthen platform is a circle made of rice straw that measures 4.55 meters in diameter. Traditionally, women are barred from entering the dohyō. This seems an odd prohibition considering that empresses were known to have occupied the Chrysanthemum Throne in ancient times and many of the main deities of Japanese mythology are female. What is more, many legends speak of women wrestling. In modern times, female politicians have objected to sumō’s moratorium on women entering the dohyō, and it is possible that the rule will one day be abolished.

In sumō, a wrestler loses if he is forced out of the ring, or anything other than the bottoms of his feet, such as hands or knees, touch the ground. It can take a long time for two rikishi to build up to a bout, but a match can be decided in a split second.

Then sekiwake Kiribayama defeats Daieishō in the final bout to win the spring tournament at Edion Arena in Osaka on March 26, 2023. The tournament was notable for the absence of rikishi from the top two ranks of yokozuna and ōzeki. (© Jiji)

The influential French poet and film director Jean Cocteau became enamored with sumō when he visited Japan in 1936. He details a match in his book My Journey Round the World, describing the crouching wrestlers springing into energetic motion, grabbing, hitting, and pulling until one is uprooted and tumbles like a human tree to the floor.

Cocteau was captivated by the vivid change from quiet to motion, calling the balance of sumō miraculous as wrestlers meet and cross in an instant. This describes the essence of sumō nicely.

Even with its origins in antiquity, sumō remains a pastime for ordinary people. It has endured waves of modernization in the nineteenth century and numerous ebbs and flows of popularity to remain a fixture of Japanese society.

Sumō Today

Sumō, however, finds itself in somewhat of a complicated situation today. Major scandals over the last few decades, such as match fixing and abuse of lower ranked wrestlers, have rocked the sport. Another issue weighing on sumō’s popularity is the lack of Japanese-born grand champions.

Yokozuna is the highest rank in sumō. They are considered more than just champions, though. In the past, yokozuna were purported to have the power to ward off evil spirits and even commune with the gods. It was considered an honorary role that called for dignity as well as strength.

Over the last few decades, the rank of grand champion has come to be dominated by foreign-born wrestlers. In fact, there was no native-born grand champion for nearly 20 years until Kisenosato was promoted to yokozuna in 2017.

Hawaiian-born rikishi Takamiyama, popularly known as “Jesse,” helped pave the way for foreign wrestlers. After retiring from the ring, he became the stablemaster Azumazeki and worked to train the next generation of wrestlers, including fellow Hawaiian Akebono, who would go on to become a yokozuna. (© Jiji)

The first foreign-born wrestler to win a tournament was Takamiyama, a native of Hawaii, in 1972. Other wrestlers from overseas who have attracted attention include Kotoōshū, a Bulgarian with wrestling experience, Baruto, an Estonian with a background in jūdō, and Ōsunaarashi, a Muslim wrestler and former bodybuilder from Egypt. The spring tournament in March 2023 featured Tochinoshin from Georgia and Kinbōzan from Kazakhstan.

The biggest foreign presence in sumō, however, are Mongolian wrestlers. The first Mongolian to become a yokozuna was Asashōryū in 2003. Since then, several of his countrymen have followed in his footsteps to achieve the rank of grand champion, including Hakuhō (2007), Harumafuji (2012), and current yokozuna Terunofuji.

Of course, the more knowledgeable a fan is about the sumō world, the more respect they are likely to have for foreign wrestlers who have come to Japan and thrown themselves into a traditional world that even Japanese people would have difficulty adjusting to. Yet, while many welcome sumō becoming more global, they might still feel that they want Japanese wrestlers to dominate tournaments. When Kisenosato became yokozuna, it gave fans high hopes. These were short lived, however, as he retired in 2019 due to injury.

Mongolian-born Hakuho (now stablemaster Miyagino) was a yokozuna for 14 years, during which time he broke numerous records, including a historic 45 tournament wins in the top-flight makuuchi division. Here he performs a ring-entering ceremony during his final appearance as a professional sumō wrestler on July 4, 2021, at Aichi Prefectural Gymnasium. (© Jiji)

Depictions of Sumō

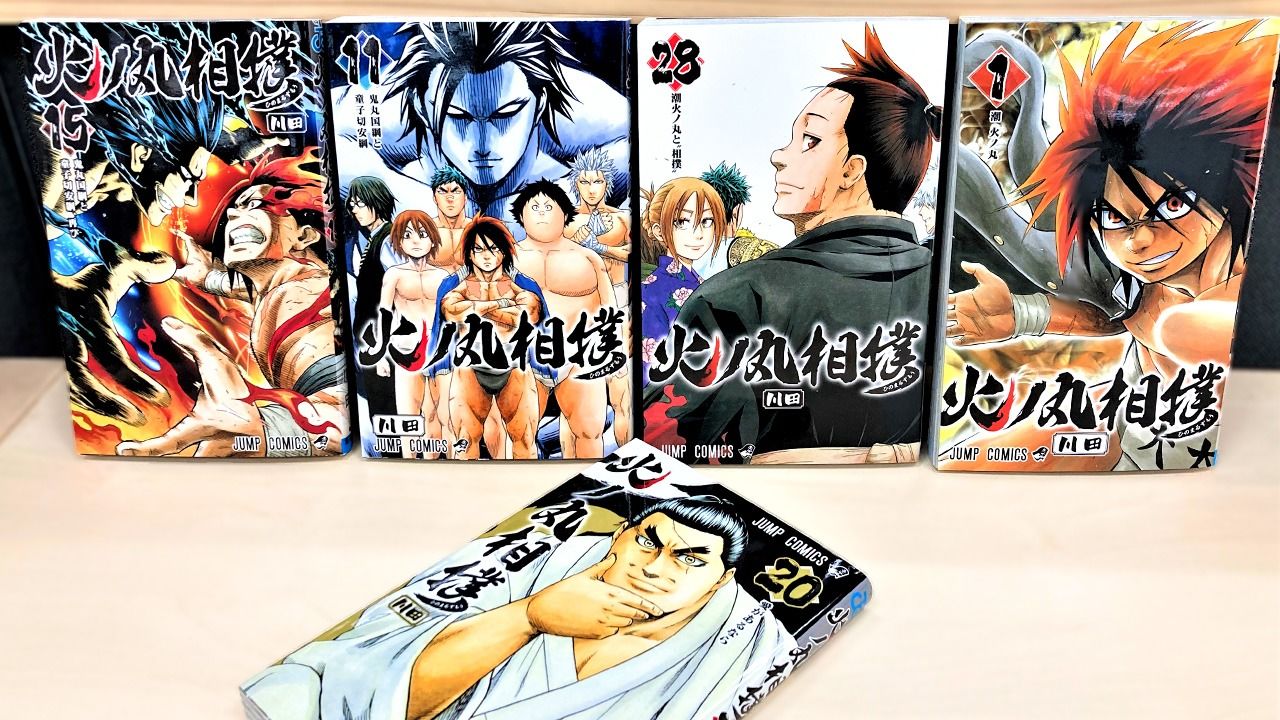

Sumō today has to compete with popular sports like soccer, and many Japanese children probably consider the sight of rikishi sporting topknots and clad in mawashi as somewhat old fashioned. At the same time, sumō offers many positive and appealing aspects for younger people. Many of these are highlighted in the sumō manga Hinomaruzumō by mangaka Kawada that ran from 2014 to 2019 in the well-known manga magazine for young boys Weekly Shōnen Jump.

The main character of the series is a boy named Ushio Hinomaru. Hugely talented, he becomes a renowned sumō wrestler while still at elementary school.

The novelist Ōsawa Arimasa once said that “when the main character loses something and regains it, that’s the kind of story everyone wants to read.” If so, what does Hinomaru lose?

The answer is that he is not blessed physically. Even after entering junior high school, he does not grow any taller and is unable to win bouts. In sumō, which has no weight categories, being physically small is an overwhelming disadvantage. In sumō, there is an ongoing trend toward “supersized” wrestlers. From the start, wrestlers need to be a certain physical height if they want to turn professional.

Despite his size, Hinomaru does not give up on his dream of becoming a grand champion and embarks on a three-year training program. He enters Ōtachi High School, and together with his new friends, he starts out on the path to becoming a yokozuna.

The television anime adaption of the series debuted in October 2018 and depicts how Hinomaru reaches the pinnacle of high school sumō. (© Kawada/Shūeisha Hinomaru Sumō Production Committee)

Although the work deals with old and traditional topics, it also ingeniously appeals to readers in fresh ways. For example, the wrestlers aiming to become yokozuna have names derived from famous Japanese swords, such as Onimaru-Kunitsuna and Kusanagi-no-tsurugi, as well as boast dramatic signature moves.

But most wonderful of all is how the characters themselves are portrayed. Victory and defeat are not decided solely by ability. Some characters have plenty of talent but are unable to make full use of it. Others try to catch up with their naturally talented peers through hard work, while others weep at their own bad luck. These young people on the path of sumō aim for ever-greater heights by making friends and fighting strong opponents. It is a heartwarming tale.

Sumō has ancient traditions, but Hinomaruzumō cultivates its own traditions of friendship, hard work, and victory. At the same time, creator Kawada uses his artistic power to portray sumō’s long tradition in the series.

The manga ran for five years and was adapted into an anime series. I have little doubt that a rikishi who discovered the appeal of sumō through Hinomaruzumō will one day appear.

週刊少年ジャンプ34号発売中です。

— 『火ノ丸相撲』公式【最終28巻12月4日発売!!】 (@hinomaru_zumou) July 22, 2019

これまで沢山の応援をありがとうございました…!

火ノ丸という力士の生きざま、その締めくくりをぜひご覧ください!

コミックス27巻は10月、28巻は12月発売予定です!! pic.twitter.com/mH13zZQ591

The world of sumō is simple, yet profound. I have watched sumō at the Ryōgoku Kokugikan, and the experience drew me into sumō’s world of refined beauty of form.

Yet, sumō is more than just an ancient sport. The Hawaiian-born wrestler Konishiki once controversially claimed that “sumō is fighting.” In fact, wrestlers collide with tremendous force and yokozuna have the ability to throw opponents with seemingly little effort. In fact, among avid martial arts fans, some argue that sumō might even be the strongest of all the standing fighting arts.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Hinomaruzumō was serialized in Weekly Shōnen Jump from 2014 to 2019. There are 250 episodes that have been compiled into 28 books. It was made into an anime series in 2018. © Nippon.com.)