Chikamatsu Monzaemon: The Tenderness and Severity of Japan’s Master Dramatist

Culture History Entertainment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Inviting Compassion

It is 300 years since the death of Japan’s great playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653–1724), known for the enduring appeal of his works in kabuki and bunraku puppet theater. Chikamatsu’s world can be both tender and severe, as I will introduce with reference to individual plays.

For example, there is Chikamatsu’s bunraku play Keisei hangonkō, which was first performed in 1708. A part of the work is still staged today in kabuki and bunraku under the name Domo mata (trans. by Holly Blumner as Matahei the Stutterer, part of The Courtesan of the Hangon Incense).

Text from The Courtesan of the Hangon Incense written by Chikamatsu Monzaemon himself, which was donated to the city of Amagasaki in Hyōgo Prefecture. (© Kyōdō Images)

The protagonist is an artist called Ukiyo Matahei, who has a speech impediment that prevents him from speaking smoothly. For this reason, his master does not bestow a formal name on him, and his younger fellow disciples are quicker to rise in the world. There is a scene where Matahei laments, “Why was I fated to be born this way?” while beating at the tatami. In the accompanying jōruri chanting, the narrator expresses his sympathy with Matahei.

While there is fellow feeling for the sorrow of the unappreciated artist here, the contemporary kabuki stage also featured imitations of stuttering played for laughs. Instead of taking this approach, Chikamatsu created a drama that invites compassion for the vulnerable Matahei in his undeserved obscurity.

“No Falsehoods or Truths in Our Love”

Chikamatsu’s gentle sympathy for the vulnerable is an aspect seen in other works too, such as his superb depictions of the bitter emotions of prostitutes, who were compared to caged birds at the time for their loss of freedom. In Chikamatsu’s Sanzesō, a prostitute speaks as follows (the words also appear in his famous Meido no hikyaku, trans. by Donald Keene as The Courier for Hell).

People say that there’s no truth in courtesans, but they’re mistaken. These are the words of those who don’t understand the subtleties of human feelings. Truth and lies come from the same place. For example, even if we sacrifice our lives and show the utmost devotion, if no message comes from a man, and he’s far away, no matter how madly we pine for him, our lot is such that we can’t do as we please. In due course, another patron buys out our contract, and the vows we swore turn into lies. Or if we meet a man at first for our trade, with no choice in the matter, and our meetings continue, then when we finally become man and wife, our initial lies become the truth. There are no falsehoods or truths in our love. It’s the relationship that’s the truth.

She insists that while society sees prostitutes as deceivers who lead men on, for these women who cannot do as they wish, there is no such thing as either lies or truth in love. Chikamatsu was a writer who could surmise the feelings of people in difficult situations and accurately depict them. For those who enjoy his works, whether through reading or hearing in performance, the flowing kindness of his narrators (and behind them, of the playwright himself) is plain. His sympathy for others is one of the great attractions of his plays.

Food for Snapping Turtles

However, Chikamatsu also has a severe side, directed toward characters who have committed some kind of crime, as seen in several of his later works.

His Tsunokuni myōto ike (trans. by C. Andrew Gerstle as Lovers Pond in Settsu Province), first performed in 1721, tells the story of a man who kills his friend, covers it up, and marries his widow.

A samurai from Suō province (now Yamaguchi Prefecture) called Reizei Bunjibei falls in love with the daughter of a retainer from the same province. He asks his married friend Komagata Ichigaku to act as a go-between, but Ichigaku says, “If I didn’t have a wife, I’d marry her myself.” Later, Ichigaku’s wife dies in childbirth, and he marries the girl before the period of mourning is over.

Unable to contain his rage, Bunjibei kills Ichigaku in secret and then marries the girl and takes her child into his family. Twenty-two years later, he has left his former clan and is living as a rōnin in Settsu province (now part of Hyōgo Prefecture and Osaka Prefecture). He confesses his crime, and urges his wife to avenge her former husband by killing him, but she cannot do so, having lived so many years together, and drowns herself in a pond. Bunjibei then drowns himself in the same pond.

This summary leaves out the plot details, but it gives a general picture of the crime and what happened afterward, as revealed through Bunjibei’s confession. It illustrates the reason for the “lovers pond” in the title (or more literally “husband and wife pond”). Unlike the pond in the legend the name comes from, the characters’ drownings are not glorified in any way.

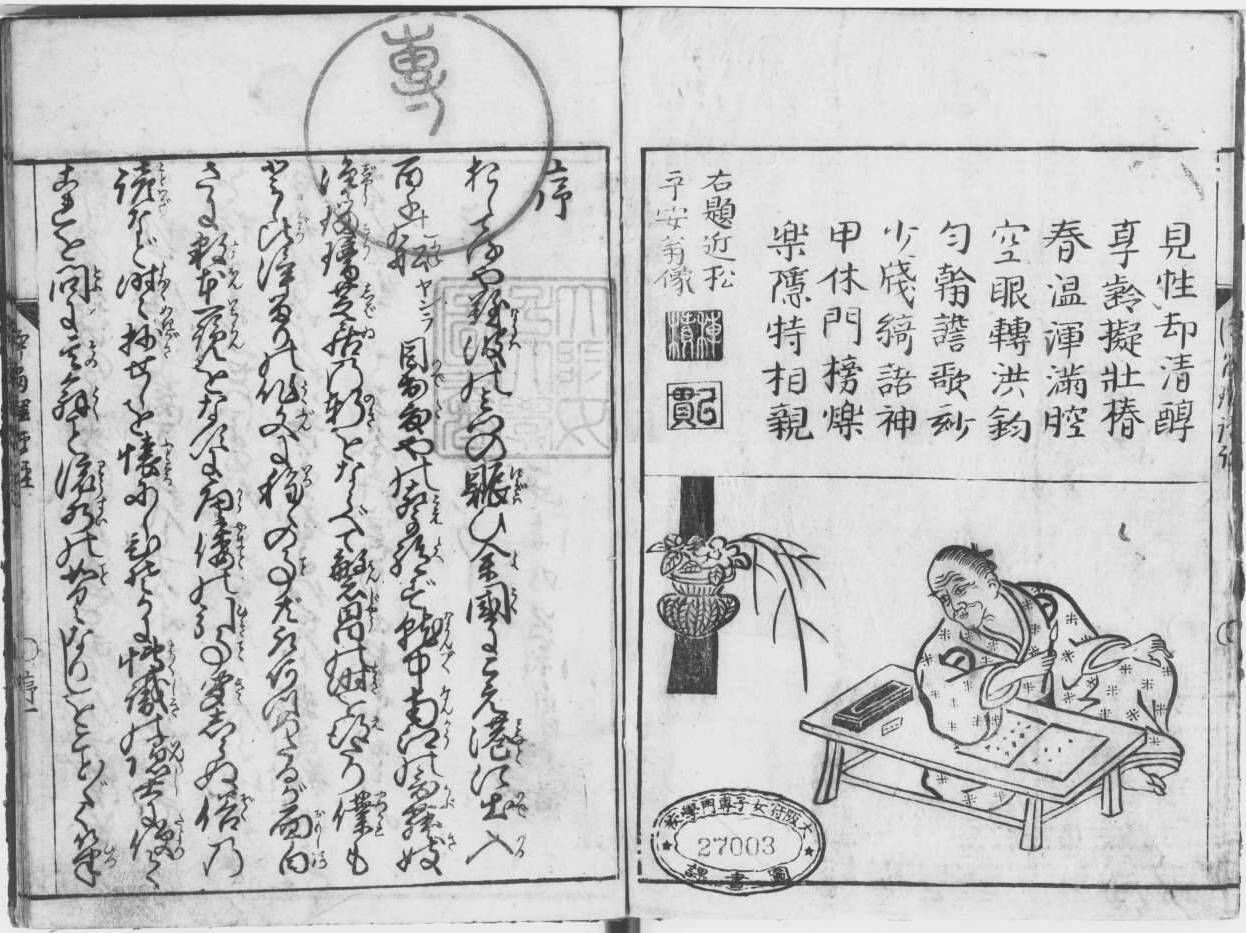

A jōruri book for Lovers Pond in Settsu Province. (Courtesy of the University of Tokyo Graduate School of Arts and Sciences)

The wife laments, “I thought I was living as a virtuous woman, but really I was a beast,” before thrusting a sword into her throat and entering the pond. Bunjibei, who had long held a sense of guilt while constantly putting off his confession, says, “This body of a beast killed a man and took his wife. Don’t burn or bury me. I’ll become food for the snapping turtles,” before he goes into the muddy water. When his child tries to prevent him, he cuts off his own arm in a battling end to his life. Such a miserable death shows Chikamatsu’s unsparing attitude to those who commit crimes. One senses almost nothing that could beautify this tragedy.

Heaven’s Punishment

The severe side of Chikamatsu can also be found in his works about shinjū, or double suicides of lovers. Shinjū ten no Amijima (trans. by Donald Keene as The Love Suicides at Amijima), first performed in 1720, is said to be his greatest masterpiece. The protagonist Kamiya Jihei is a paper merchant, married with children, who neglects his business for an affair with the prostitute Koharu. He makes his wife Osan and his brother Magoemon suffer before finally committing suicide together with Koharu.

The suicide of the immoral couple is quite different from the beautiful scene in Chikamatsu’s Sonezaki shinjū (trans. by Donald Keene as The Love Suicides at Sonezaki), which might be taken as a model for lovers. Jihei and Koharu deliberately kill themselves in different places, out of duty to Osan. Jihei first stabs Koharu on a bank near the temple of Daichōji in Amijima (now part of the city of Osaka) before strangling himself with her obi belt at a nearby sluice gate.

These deaths are certainly not aestheticized. Jihei tries to cut Koharu’s throat, but the blade does not meet it cleanly, and she suffers in pain until her agitated lover finally kills her with a second thrust. When Jihei hangs himself at the sluice gate, slowly dying in agony, he is compared to a gourd swaying in the wind, as if to dispel all sentiment. The play’s title references a proverb saying that heaven’s net appears coarse, but it does not let any evildoers pass through; any wicked deeds are sure to be punished. Chikamatsu depicts that heavenly punishment realistically and unsparingly. This severity is also an element in the playwright’s appeal.

A portrait of Chikamatsu Monzaemon in Naniwa miyage (preface by Hozumi Ikan trans. by Michael Brownstein as Souvenirs of Naniwa). (Courtesy Osaka Metropolitan University Nakamozu Library)

However, one may also feel some tenderness amid Chikamatsu’s severity toward these kinds of character. In the two works discussed above, the protagonists suffer and die in punishment for their sins, but Chikamatsu does not leave them there.

At the end of Lovers Pond in Settsu Province, it is stated that the story is the origin for the name of Myōto-ike, or Lovers Pond. The narrator also says that the water became yorube no mizu, which is placed in vessels before the gods in the belief that they will enter into it. While previously, the pond was described as being made up of turbid or muddy water, it is implied that the spirits of the lovers entering it have purified it so that the water can be used in such a ritual. These final words hint at salvation for the couple.

There is a similar process at the end of The Love Suicides at Amijima, where Buddha’s vow to save all living things is also compared to a net. It is suggested that although Koharu and Jihei have suffered heaven’s punishment, they will be caught in Buddha’s net and ultimately be able to achieve enlightenment. Taking such points into consideration, Chikamatsu seems, after all, full of tenderness and warmth for his characters.

Heike nyogo no shima (trans. by Donald Keene as The Heike and the Island of Women) is also known as Shunkan, after its main character, who is exiled to a remote island. In one scene, Shunkan expressing his regret is described as having the heart of a bonbu; the Buddhist term means an unenlightened person, living in a world of delusion.

Chikamatsu himself likely saw Shunkan, along with Bunjibei and Jihei, as unenlightened. However, bonbu can also mean an ordinary person. Bunjibei and Jihei are ordinary, and we too could come to act like them if we take a wrong step. From this perspective, Chikamatsu shows his empathy for many different kinds of people, which means that we are not left with a bad aftertaste when we read or watch his works.

Three centuries after his death, I appreciate the opportunity to enjoy Chikamatsu’s plays, and here I have attempted to reflect on them once more.

(Originally published in Japanese on November 22, 2023. Banner image: Portrait of Chikamatsu Monzaemon. Courtesy of the Tsubouchi Memorial Theater Museum, Waseda University.)