Astroscale: Cleaning up Space Junk for a More Sustainable Future

Environment Technology- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Crowded Skies

Founded in 2013, Astroscale is focused on cleaning up space junk and servicing satellites in orbit. It has launched a series of missions to show that tools can be developed to tackle a seemingly insurmountable problem.

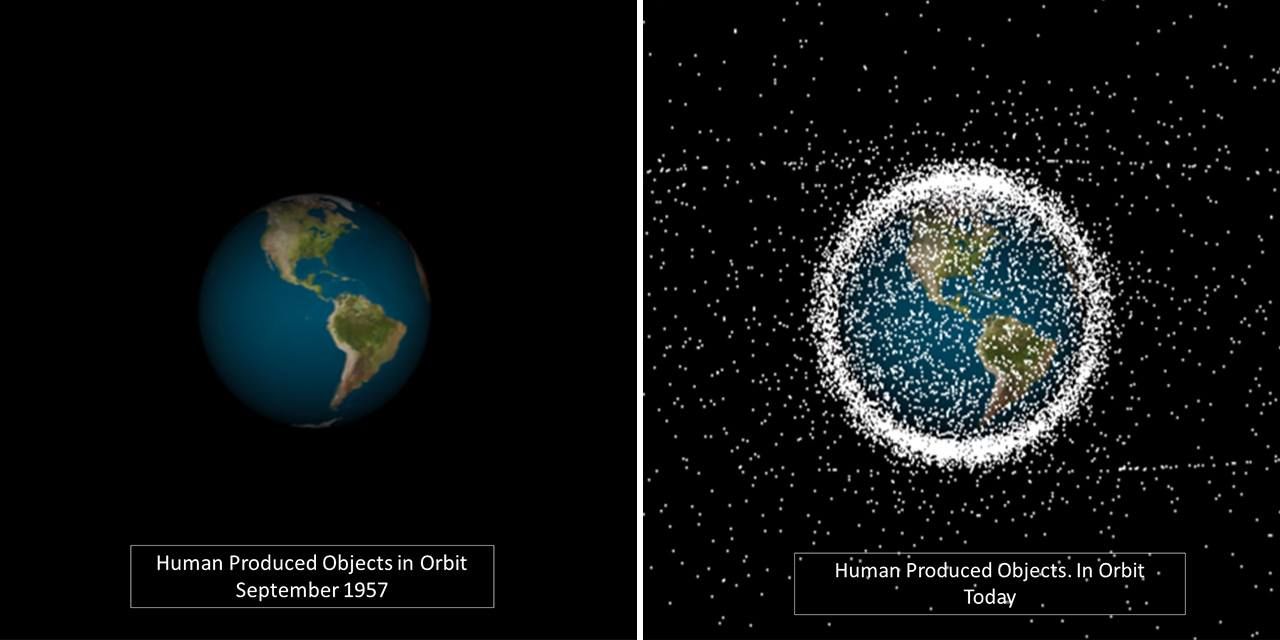

In 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, a basketball-sized satellite that became the first human-made object to orbit the earth. Over the past seven decades there have been countless more satellite launches, and orbital space has become indispensable for communications and observations of our planet. But humanity’s colonization of this space has also left a legacy of discarded rocket stages, dead satellites and other objects. These more than 36,000 high-speed “debris bombs” threaten satellites, space vehicles, and other infrastructure, and could produce thousands more fragments if they collide, exacerbating the problem.

Human-produced objects in orbit at the dawn of the space age and today. (Courtesy of Astroscale)

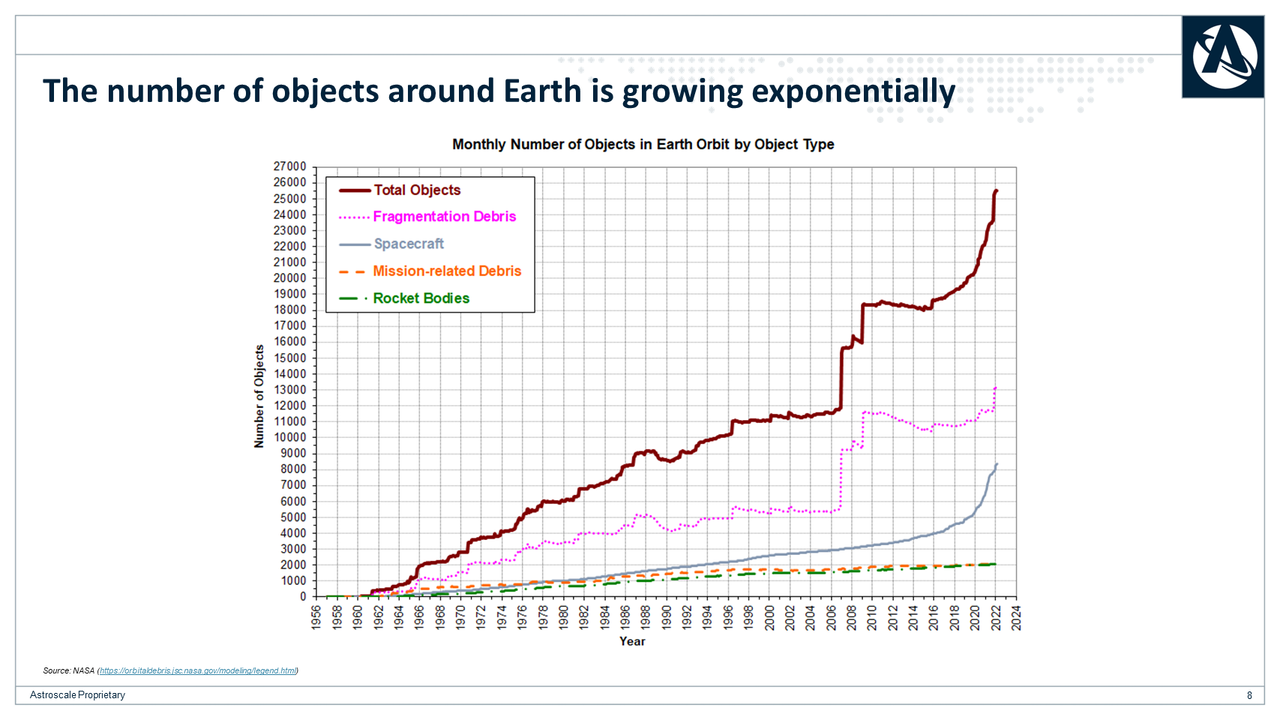

A chart showing the number of objects(*1) bigger than >10 cm in low Earth orbit. (© NASA ODPO; courtesy of Astroscale)

Seeing Trash as Treasure

In April 2013, entrepreneur Okada Nobu was facing a midlife crisis from cutthroat competition in the IT industry and casting about for new business ideas. He attended the European Conference on Space Debris, where panelists discussed the issue, and was instantly seized by orbital cleanup as both a business opportunity and an environmental necessity. Within a week, he founded Astroscale, a name that refers to the importance of balancing growth with environmental preservation. Okada used his own savings to establish the company, soon hiring a team in Singapore and then opening an R&D center in Japan.

“The space industry has had a throwaway culture with onetime use and disposal and that’s why spacecraft were not recycled, reused, relocated, refueled, or removed. Astroscale was born to bridge that gap,” says Astroscale CEO Okada Nobu. (© Nippon.com)

Cleaning up space junk was a bold idea, but one that presented major hurdles. “At the beginning, not many people supported our mission and people told me it would be impossible to develop technologies to rendezvous and capture debris, not to mention making a successful business case or influence government policies,” says Okada. “But when I heard there’s no market, that meant there are no competitors.”

The enormous junk pile of discarded rocket parts, satellites and other debris up above—the European Space Agency estimates its mass at more than 9,300 metric tons—actually does present a large business opportunity. That’s because many of the things we take for granted in everyday life depend on satellites: weather forecasting, GPS mapping, satellite TV broadcasting, satellite imagery for farming, and national security, to name a few.

Other Astroscale services under development include cleaning up larger debris such as used upper stages from launch vehicles, providing motion analysis of objects in orbit, and extending the life of geostationary satellites, which could generate more than $4 billion by 2028, according to independent estimates cited by the startup. Okada wants Astroscale to be not just a cleanup company but a satellite service provider. With the right technology, space junk could be seized and put on an orbital path to safely burn up in Earth’s atmosphere, while viable satellites could be serviced to extend their life.

“My goal is to make on-orbit servicing routine by 2030,” says Okada. “When highways on the ground became jammed with accidents or cars that ran out of gas, we never ask drivers to stop driving. We bring about better traffic rules, monitoring, and road services to ensure the flow of cars is sustainable. We need the exact same thing in space. The space industry has had a throwaway culture with onetime use and disposal, and that’s why spacecraft are not recycled, reused, relocated, refueled, or removed. Astroscale was born to bridge that gap.”

Building Space-Sweeping Technology

One milestone on the road to that goal was attained in 2021, when Astroscale launched ELSA-d, or its End-of-Life Services by Astroscale demonstration, a mission to show that capturing orbiting debris is feasible. A satellite was launched along with a 17-kilogram object that served as mockup debris. The two were separated in space, and then the satellite extended a large magnetic boom and captured the dummy debris by locking onto its ferromagnetic plate. The demonstration was successful, and the spacecraft and debris were put on a deorbit path that will cause them to burn up in Earth’s atmosphere.

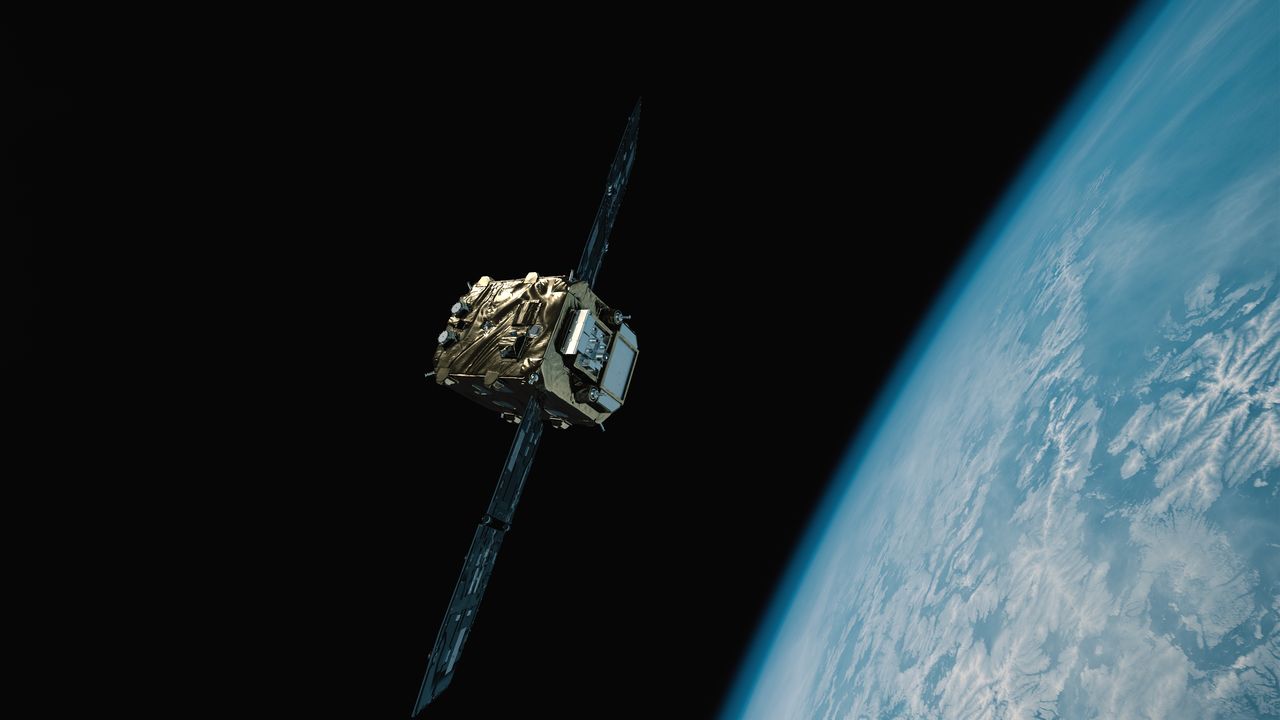

In February 2024, Astroscale launched what it describes as the world’s first space debris inspection spacecraft, dubbed Active Debris Removal by Astroscale-Japan, or ADRAS-J. Operating under the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Commercial Removal of Debris Demonstration program, ADRAS-J represents the first attempt to approach and survey a large piece of existing space debris, namely the upper stage of a Japanese H2A rocket launched in 2009. Using Astroscale’s accumulated knowledge in rendezvous and proximity operations, it will approach and capture images of the object to study its condition and movement as a first step in the process of better handling such debris.

The ADRAS-J mission will attempt to rendezvous with a discarded upper rocket stage in low Earth orbit. The satellite will match the object’s speed and rotation before photographing it. (Courtesy of Astroscale)

Orbiting at about 600 kilometers above Earth at a speed of approximately 8 kilometers per second, the upper stage is some 11 meters long and weighs roughly 3 tons. In addition to being big and fast, it’s also unprepared, meaning it’s an uncontrolled object that does not send location data or have visual aids to allow docking for servicing or removal. The team managing ADRAS-J has its work cut out—it will have to carefully position the spacecraft near the rocket stage and avoid collisions.

“This is an incremental step toward achieving our vision,” says Chris Blackerby, director of the board and chief operating officer at Astroscale. “JAXA hired us to prove we can approach and photograph the rocket stage, measuring and matching its rotation. The next phase is to go to the same object, grab it with a robotic arm, and get it out of the way.”

Chris Blackerby, director of the board and chief operating officer at Astroscale, describes the ADRAS-J mission as an “incremental step” toward achieving the company’s vision. (© Nippon.com)

Changing Mindsets Around the World

Astroscale has not yet won a contract for that next mission, but it faces little competition. With a staff of 550, this startup of self-described “space sweepers” wants to be a pioneer in a new space service industry. The company is now generating revenue through contracts such as the JAXA mission, and it has raised about $383 million from Japanese and international investors through seven financing rounds. It has also continued to build its presence outside Japan, establishing subsidiaries in Britain, the United States, France, and Israel; about 65% of its staff are non-Japanese.

The office was designed to look like the deck of a spaceship, with conference rooms named after various orbits around Earth. (© Nippon.com)

Astroscale recently completed a new head office in Tokyo’s Kinshichō district equipped with a large clean room for spacecraft assembly, a mission control center, and an office space that is designed to look like the deck of a spaceship, with conference rooms named after various orbits around Earth. There’s also a display area to improve understanding of the role of satellites—visitors are invited to try to catch little balls representing debris whipping around an air-pressurized model of Earth. It’s all part of the company’s bid to encourage the sustainable use of space.

Visitors are invited to try to catch debris whipping around an air-pressurized model of Earth. (© Nippon.com)

While there is no global treaty to stop space debris, the United States, EU, and United Nations have published guidelines to mitigate the problem. The “25-year rule” calls for spacecraft in low Earth orbit to have a lifetime that is as short as possible, but no more than 25 years after mission completion, after which they must be de-orbited. The US Federal Communications Commission and the European Space Agency recently shortened their guidelines to five years. These policies reflect the importance of preserving space and show the industry’s thinking has been evolving, according to Blackerby.

“Generationally, we’re moving toward a shift,” he says. “I was born in the early 1970s, soon after the first Earth Day. We’re not that far removed from a completely disruptive mindset in terms of how we take care of the environment. When you look at about two generations, the mindset around ecological preservation is strong. And the mindset around advancement while also making sure we’re responsible for future generations is more embedded now than it was when I was a kid.”

As for Astroscale founder Okada, he’s not resting on the laurels of the company’s successful missions.

“By 2030 space will even far more congested, and we need road service,” he says. “We are pioneering those technologies, and this may be too much to say, but without Astroscale, who else can do this? We have to make haste. Otherwise nobody will be able to enjoy the benefits of space.”

(Originally published in English. Banner photo: In February 2024, Astroscale launched the world’s first space debris inspection spacecraft, dubbed ADRAS-J, Active Debris Removal by Astroscale-Japan. Courtesy of Astroscale.)