Shirow Masamune and the Predictions of “Ghost in the Shell”

Entertainment Art Manga Anime Design- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Foretelling the Internet Age

In a sense, Ghost in the Shell predicted the world we live in now.

The original manga grew famous after director Oshii Mamoru’s 1995 animated feature adaptation. His Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence was the first Japanese animated film selected for the Competition section of the Cannes International Film Festival and garnered critical acclaim for its artistry and intellectual depth.

The original manga began serialization in 1989. If we take 1995 as “year zero” for the internet age, then its depiction of widespread computer network use, people making hands-free telephone calls, “hacking” of people’s perception of reality and the world, and an increasing inability to distinguish what is real from what is artificial are shockingly prophetic. The idea of full-body cyborg prostheses could also be seen as foreseeing people using digital avatars or even cosmetic surgery to distance themselves from the bodies they were born with, as the modern age sees greater desire to freely shape the human body.

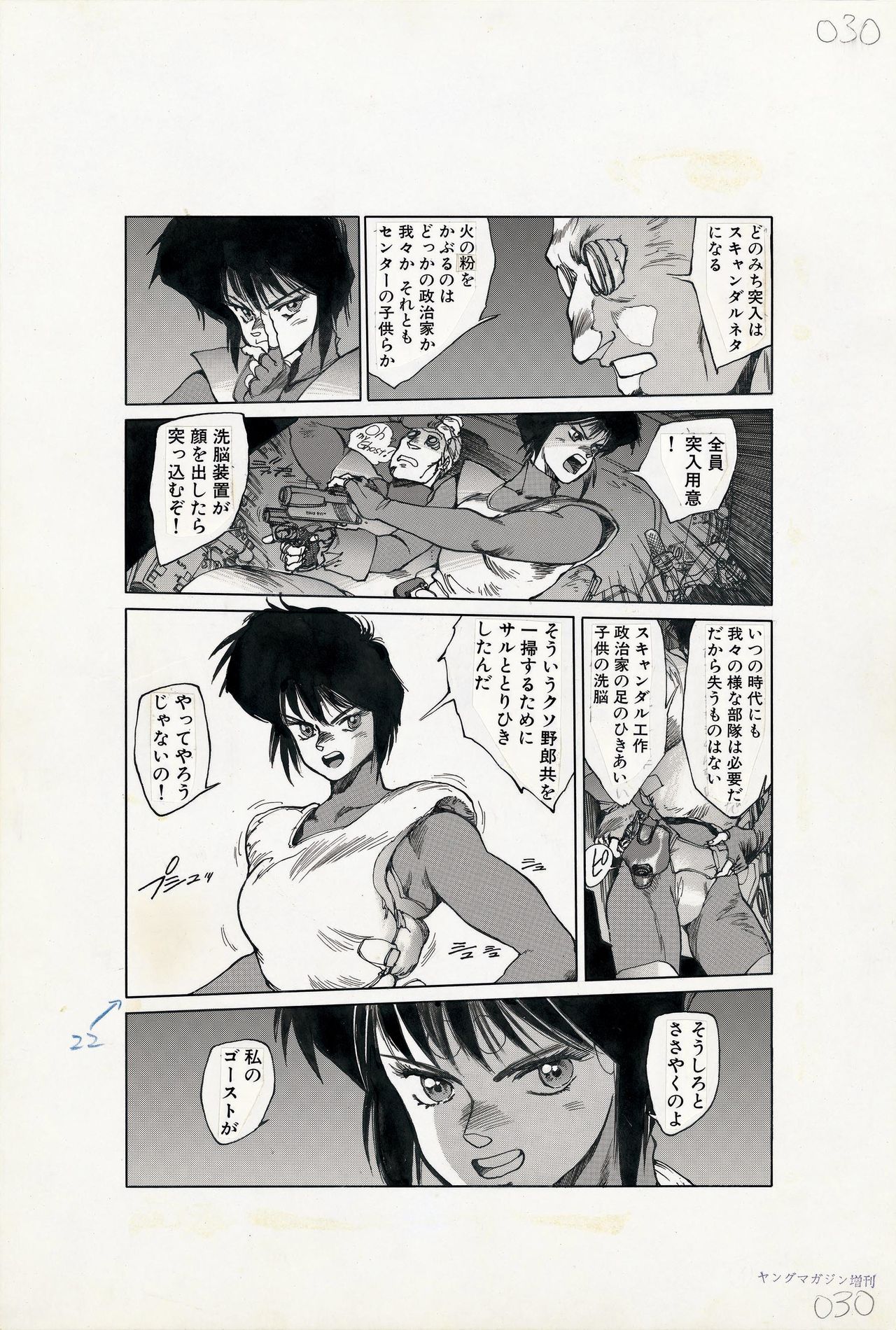

An original page from Ghost in the Shell at the time of its serialization. Taken from the May 1989 issue of Young Magazine kaizokuban. (© Shirow Masamune/Kōdansha)

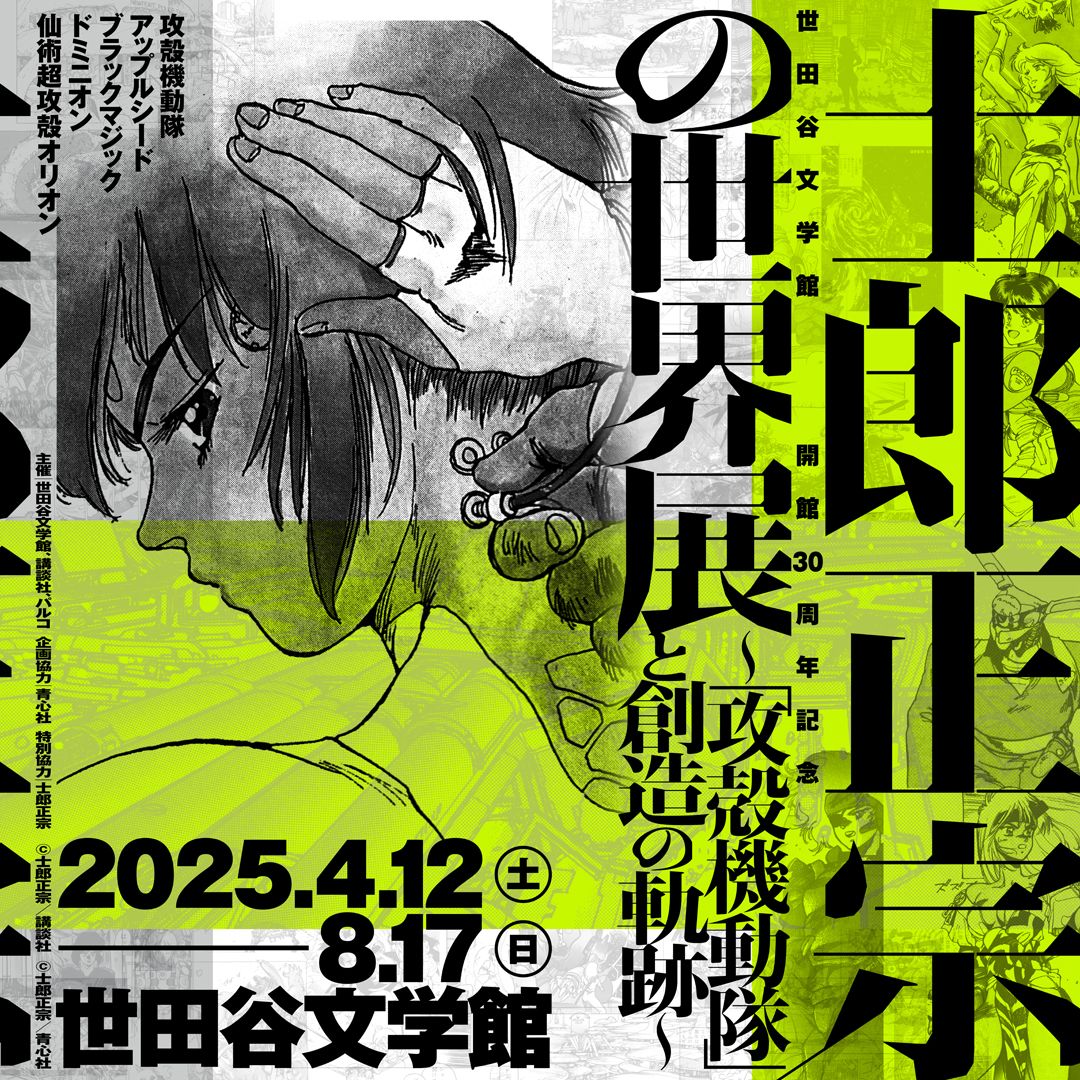

The secret to this prophetic power is revealed at “The Exhibition of the World of Shirow Masamune: The Ghost in the Shell and the Path of Creation,” which ran until August 17 at the Setagaya Literary Museum in Tokyo and is on from September 5 at Shinsaibashi Parco Osaka. The exhibition shows that Shirow was an avid reader of various scientific magazines.

His science reading started when he was a boy, which brought him into contact with new ideas and visions of the future. The influence of logical extrapolation and visual association likely helped his own predictive abilities.

The entrance to the Shirow Masamune exhibition at the Setagaya Literary Museum in Tokyo. (© Shirow Masamune/Kōdansha)

The Touch of Fantastic Realism

The exhibition also shows how Shirow was influenced artistically by the Vienna school of fantastic realism.

This was an artistic movement in postwar Vienna that married concrete representational elements with fantastic and sensual worldviews. Historians have described it as a reaction to the traumas of war as well as pointing out elements of social caricature.

Ghost in the Shell is set after the devastation of nuclear war. It depicts Japan, recovering from the trauma of that war, having rebuilt itself as a “scientific technological nation” with double the GDP of the 1980s.

Shirow took artistic influence from fantastic realism, adopted the plot and setting of commercial shōnen manga, depicted Japan’s postwar scientific and technological rebirth in a cyberpunk style, and predicted much of the future we have today.

An Ode and Response to Cyberpunk

To really understand the time and social context surrounding Ghost in the Shell, we must talk about cyberpunk. This subgenre of science fiction rejects rosy visions of a utopian future, instead drawing on gloomy techno-urban landscapes as settings for stories about networks and cyborgs.

An installation from the exhibition during its Tokyo outing. (© Shirow Masamune/Kōdansha)

Key works in the subgenre include William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer and Ridley Scott’s 1982 film Blade Runner.

Neuromancer starts off in Chiba Prefecture. Blade Runner features a future Los Angeles filled with Japanese language advertisements. It imagines a United States that has been “Japanified,” or “Asiafied,” under the influence of Japan’s enormous economic growth in those days.

Both stories deal with the intellectual struggle of cultures melding and of knowing what is real and what is fake, what is the original and what is the copy. Here, the implications of “fake” and “copy” touch on Japan’s technological development despite it not sharing in the “Western spirit” of the United States.

Ghost in the Shell is set after the third nuclear world war/fourth nonnuclear world war, and in this world, Asia was the winner. This is a clear counterstrike at those original cyberpunk works.

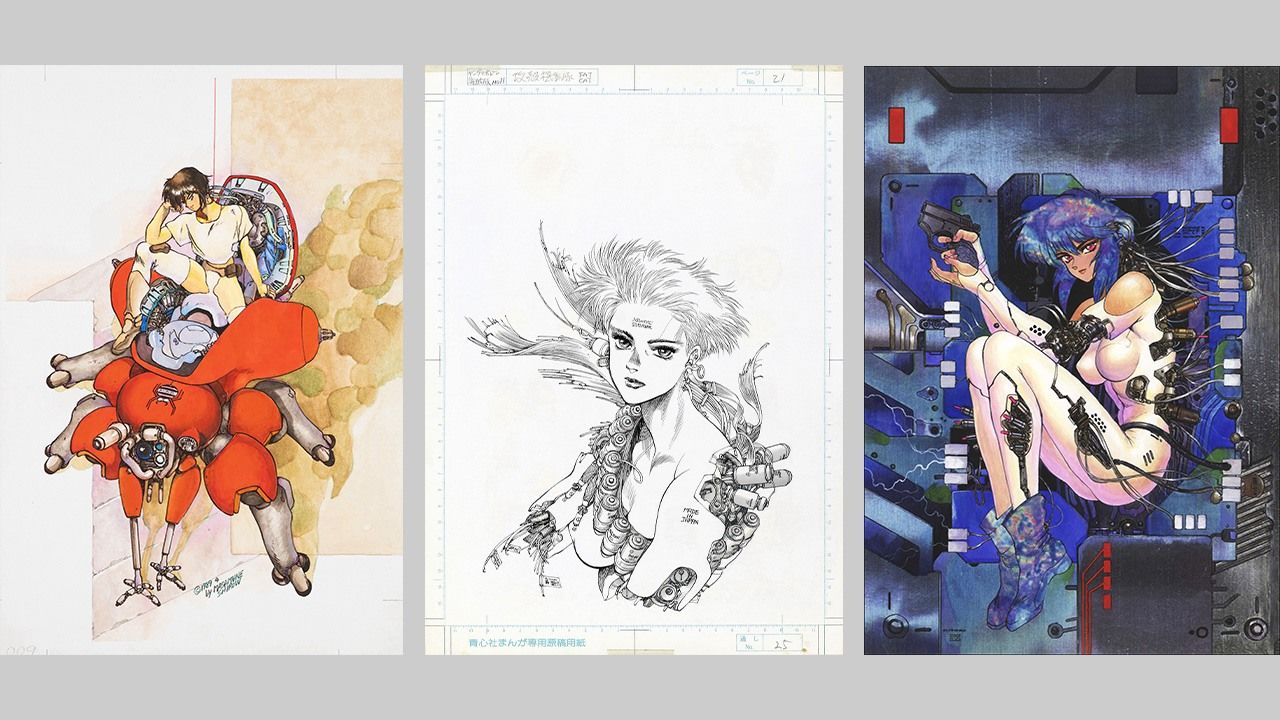

Art from the manga on display at the exhibition. (© Shirow Masamune/Kōdansha)

In Susan Napier’s Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation, she describes anime as being influenced by Japan’s loss in World War II and experience of nuclear bombing, and then being reborn, or born anew. Japan lost much of its traditional values, spirituality, and national identity through American occupation, and so suffered a dilemma of traditional group mentality and society when it was reborn as a democratic, scientific and technological nation. Many critics understand the common anime motif of mechanical bodies as “replacements” to stem from that dilemma.

Kusanagi Motoko, the protagonist of Ghost in the Shell, and others in the story have been transformed into cyborgs through technology. This is an interrogation of how people who were developing a new society in postwar Japan even as it was becoming a “copy” of the West constructed their own identities. (In other creative spheres, too, like video games, we see offerings like the 1988 Snatcher that come across as other early Japanese responses to cyberpunk.)

The Structure of Cultural Identity

Ghost in the Shell and other Shirow Masamune works are filled with Japanese and Asian perspectives. The best examples are in 1991’s Senjutsu Chōkōkaku Orion and 2001’s Ghost in the Shell 2.

We can summarize those as such: “Do not view ideas, language or information as superior to the body,” and “Reject mind/body duality.” Shirow does not believe that the spirit or consciousness, as represented by the word “ghost,” can be removed from the body itself. He believes that the brain and nervous system, the body, and by extension the environment, city, nature, and space itself, are all part of one complex network. This relates to the Buddhist concepts of anattā—the doctrine of “no self,” signifying that no eternal soul exists separately from the surrounding reality of existence—and pratītyasamutpāda, or “dependent origination,” meaning that all phenomena are in dependence on one another.

Even as he displays style that copies the elements of a Viennese art school and Western cyberpunk, Shirow’s strategy is to blend traditional Asian values, spirituality, and philosophy with new age ideas and inject them into the work’s core concept of life. In a sense, this is a critique of postwar Japan and embodies the problems with cultural identity in a changing world.

Proof pages from Shirow’s work at the exhibition. (© Shirow Masamune/Kōdansha)

Ghost in the Shell and Human Potential

Now let us try to place Ghost in the Shell among the trends of today.

There are global “imaginations” that link concepts of technology as the embodiment of Western, local values—rather than a human universal—to ideas of racial or cultural traits and history. One example is Afrofuturism, a cultural movement linking technology, futurist ideas, and the African diaspora. Ghost in the Shell takes a similar structure, if from an opposing conception.

In other words, it constructs a historical philosophy—a story about how science and technology transform the world, striving to find connections with the past and tradition as they creates the new. Shirow’s work and worldview mesh neatly within that story.

The world still has war and conflict between races, nations, and religions, even as expectations and anxieties about the age of AI grow. No less a spiritual figure than Pope Leo XIV has spoken about addressing the issues of humanity, morals, and spirituality in the time of AI.

In Ghost in the Shell, Shirow melds wisdom gained from Eastern and Western ideas and philosophy, shows that there is possibility to connect tradition to our present age. In doing so he offers a kind of stimulus for humanity to imagine and create a better future.

The Exhibition of the World of Shirow Masamune: The Ghost in the Shell and the Path of Creation

- Exhibition website (in Japanese only):

https://www.shirow-masamune-ex.jp -

The exhibition runs at the Shinsaibashi Parco in Osaka from September 5 to October 5, 2025.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: from left, the frontispiece art for Ghost in the Shell from the May 1989 and November 1991 issues of Young Magazine Kaizokuban and the cover art for the standalone edition of the manga. © Shirow Masamune/Kōdansha.)