Mapping a Shaky Seafloor to Support Noto Fisheries

Environment Disaster- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Seafloor Uplift Delays Wajima Fisheries Recovery

On September 4, 2025, the Wajima branch of the Ishikawa Prefecture Fisheries Cooperative Association held a briefing on how to use a brand-new ocean map. Local fishers, many of them women freedivers called ama, followed the presentation attentively.

The Port of Wajima had boasted the largest number of fishing vessels and the highest catch volume in Ishikawa Prefecture. However, the January 1, 2024, Noto Peninsula Earthquake damaged its quay walls and port facilities. The area around Wajima’s morning market, previously a bustling tourist spot with plenty of fresh seafood on offer, suffered a massive fire that burned down some 250 buildings across roughly 50,000 square meters.

About 40 people attended the presentation, many of them ama divers. (© Nippon.com)

Clockwise from top left: The morning market when it was bustling with tourists (© Pixta). Iroha Bridge, which once served as the western gateway to the morning market, is now closed. The other side is overgrown with weeds (© Nippon.com). Shops selling seafood once lined both sides of the street beneath retro-style streetlights (© Nippon.com).

One major obstacle to the recovery of the fisheries is the uplift of the seafloor, one of the largest ever recorded. Around the Port of Wajima, the seafloor rose 1.5 to 2 meters, making it necessary to install temporary piers at unloading sites to allow boats to dock. With shallower waters and limited docking space, multilayered mooring, with multiple boats stacked up off of each berth, has become routine, and large vessels now have to use other ports, such as Kanazawa, some 90 kilometers to the south.

The region’s traditional freediving fishing, recognized as an Important Intangible Folk Cultural Property under the name “Wajima’s ama diving techniques,” has also been impacted significantly. Torrential rains in September 2024 caused sediment to flow into the sea, and ama divers have been busy surveying the altered fishing grounds ever since.

A boat docked next to a temporary pier. The seafloor at the original unloading site has risen by about 1.5 meters. (© Nippon.com)

Clockwise from top: At Kamogaura, a scenic spot near the Port of Wajima, the view has changed with a ground uplift of more than 2 meters. Nearby are spots where ama divers harvest turban shells and seaweed (© Nippon.com). The walking path to Sodegahama Beach to the west had been cut off by a landslide (© Nippon.com). A photo from before the earthquake, when the area was under seawater (© Pixta).

Measuring the Seafloor Before and After the Quake

Offering hope to those involved in fishery is the Umi-no-Chizu Project, an ocean-mapping initiative promoted by the Japan Hydrographic Association and supported by the Nippon Foundation. The project uses airborne laser surveys to map shallow coastal waters up to 20 meters deep. It aims to complete seafloor maps for about 90% of Japan’s 35,000 kilometers of coastline in a 10-year plan launched in 2022, promising the benefits of safer navigation and disaster mitigation.

The northern part of the Noto Peninsula had already been surveyed in autumn 2022, but after the earthquake and seafloor uplift, another survey was conducted from April to May 2024. For the first time in the world, detailed data comparing seafloor topography before and after an earthquake was obtained. Seafloor uplift from earthquakes had previously been estimated to reach a maximum of 4 meters. However, measurements near Cape Saruyama in Wajima showed a maximum uplift of 5.2 meters.

Ishikawa Ryōko from the Wajima Seaweed Lab has been coming to Wajima for more than 10 years, working with ama divers to survey marine resources. “I heard about the ocean mapping project. I thought it would be useful not only for research but also for finding new fishing grounds, so I asked if it could be made available for the affected areas,” she recalls. Similar requests had been reaching the Nippon Foundation, which supports disaster recovery in various fields. It was then decided that the map for northern Noto would be released ahead of schedule.

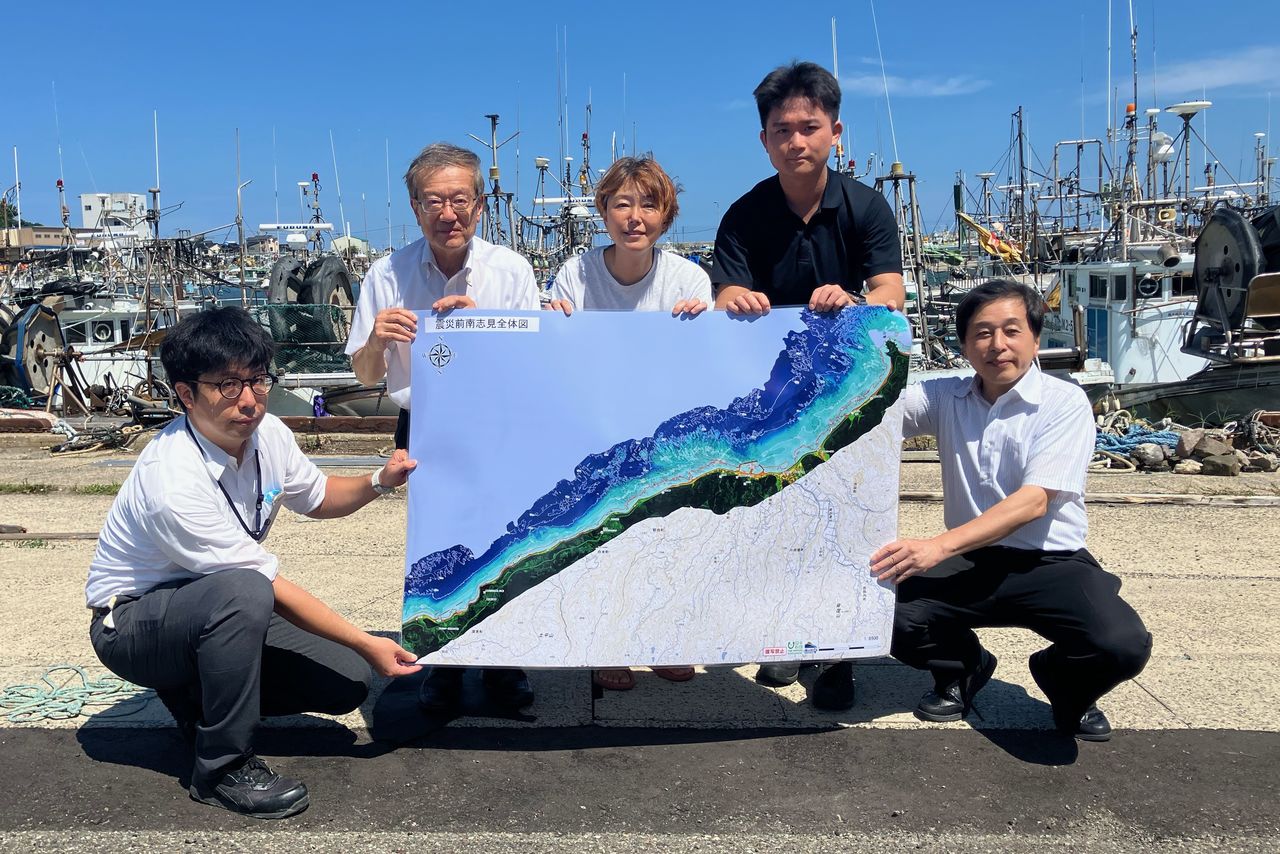

Ishikawa Ryōko (center) with members of the Umi-no-Chizu Project. (Courtesy the Japan Hydrographic Association)

Behind the fisheries cooperative, boats are moored in layers like double-parked cars. (© Nippon.com)

Utilization for Sustainable Fishing and Ocean Safety

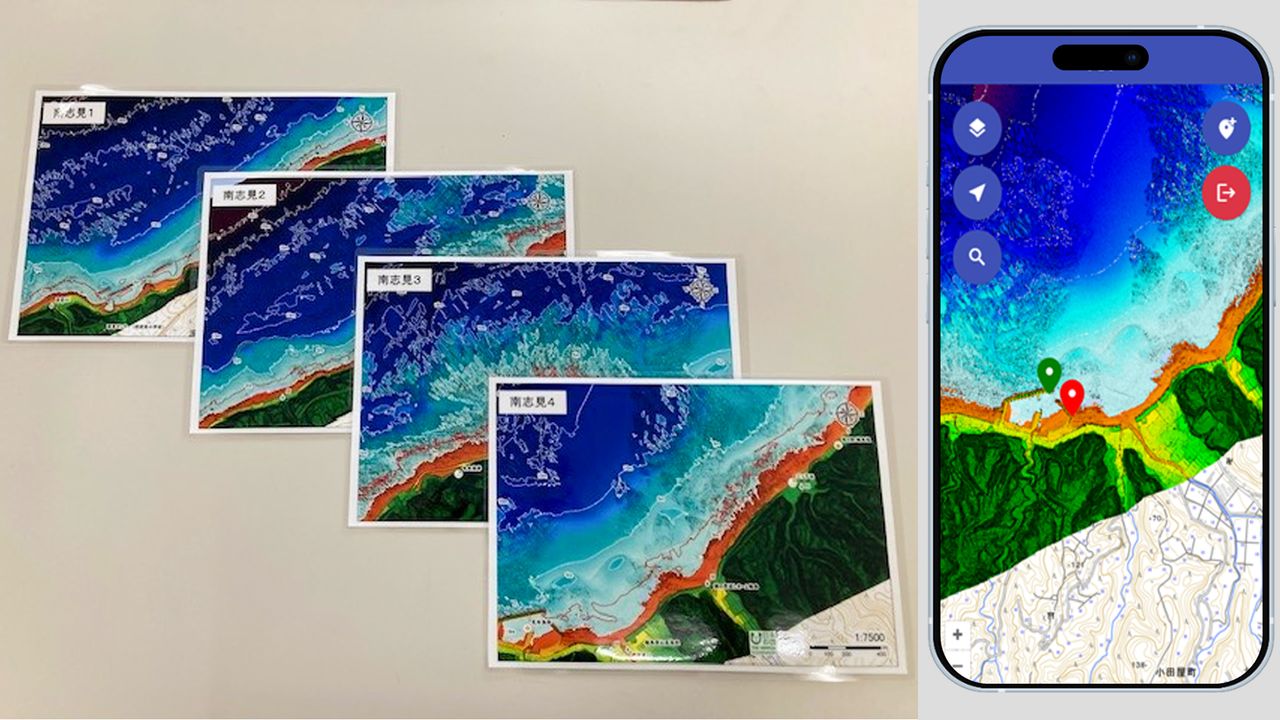

Map data began to be shared in June as a trial, and ama divers made requests—such as for the addition of place names, detailed contour lines, and a paper version of the map. The map was refined based on the feedback, and the smartphone and paper versions were released early.

A member of the Wajima Ama Diving Preservation and Promotion Association says: “Until now, we had been using blank maps without contour lines, so we couldn’t tell which areas were sandy or rocky. Since we use boats to reach the fishing grounds, this will make us feel more secure when heading out.”

Waterproofed paper versions and the smartphone version of the map. (Courtesy the Japan Hydrographic Association)

Members of the Wajima Ama Diving Preservation and Promotion Association with Ejiri Kazuki from the Najimi area at right. (© Nippon.com)

So far, maps are being provided for the Wajimazaki area around the Port of Wajima and the Najimi area where Nafune Port is located. The plan is to expand coverage to municipalities including Suzu and Noto to complete the northern Noto Peninsula area, so that the map can be utilized in seawall repairs and sediment dredging.

Ejiri Kazuki, a fisherman working out of Nafune Port, plans to use the map for preventing maritime accidents. “We warn children and the elderly that it’s dangerous, but because changes on the seafloor aren’t visible, it seems it’s difficult for them to understand the risk. This map will make it easier to explain.” He also expressed hope: “The seafloor uplift may open up access to new fishing grounds that haven’t been developed yet.”

“We’re not yet at the stage of resource management,” says Ishikawa Ryōko, “but are just surveying how much remains. This foundational work is being compiled on the ocean map. My hope is that this resource will contribute in some way to the creation of a sustainable business model for the region’s ama divers.”

The Umi-no-Chizu Project’s mapping of Japan’s seas is only 37% complete. However, by incorporating the requests and experiences from Noto, the organizers now see the potential to make this ocean map even more practical. Hopes are high for a complete public release in the near future.

Nafune Port, where recovery work is still ongoing, is still littered with driftwood. (© Nippon.com)

(Originally published in Japanese. Reporting, text, and photos by Hashino Yukinori of Nippon.com. Banner photo: The Nafune Port area in Wajima, uplifted by the earthquake, and the smartphone version of the ocean map. The white parts of the wave breakers were underwater before the earthquake. © Nippon.com.)