From Calligraphy to Anime: Traditional and Contemporary Cultural Bridges Between Japan and the Arab World

Culture Arts- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japanese and Arabic Calligraphy Come Together

In the banner photo above, Yamamoto Naoki, a scholar of Islamic thought based in Turkey, has written the kanji 奉 (hō or tatematsuru) in calligraphy. Rotating the kanji clockwise creates سُبْحانَ الله, subhanallah in Arabic. In Japanese, tatematsuru (to hold in high esteem) is used in humble speech when speaking of someone honored or held in high esteem. The rotated Arabic term, meanwhile, means “Glory be to Allah,” a word recited by Muslims during prayer—interestingly enough, a term carrying a nuance similar to that of tatematsuru.

Rotating the kanji tatematsuru clockwise produces the Arabic سُبْحانَ الله (subhanallah). (© Nippon.com)

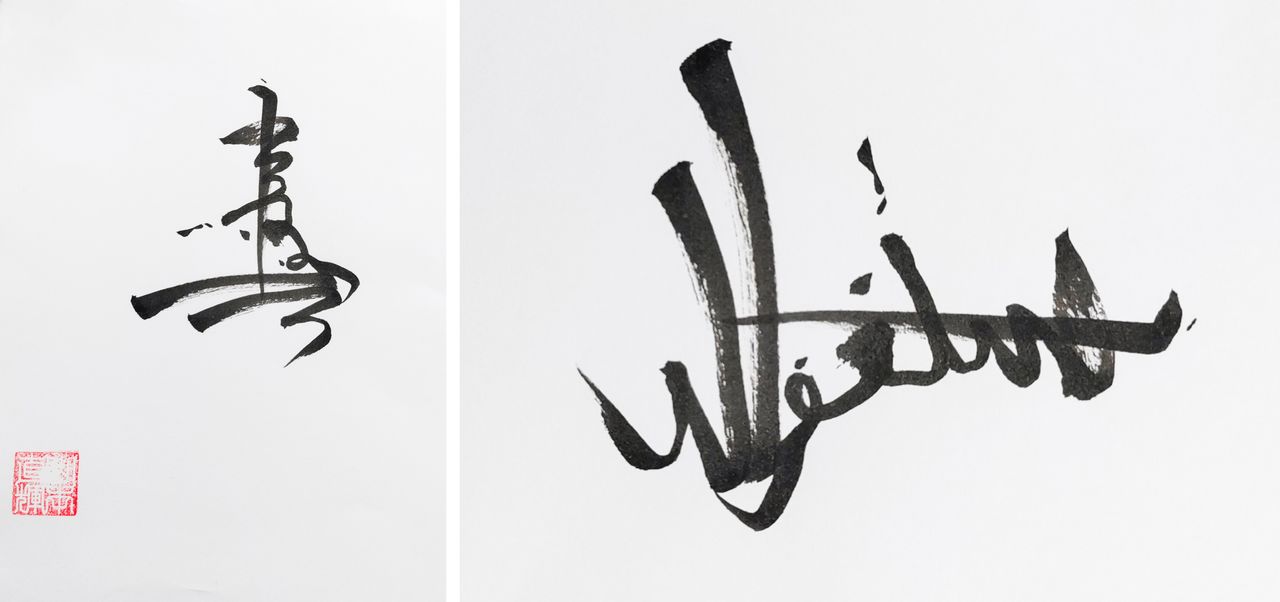

Another of Yamamoto’s works, a stylized take on 寿 (kotobuki, “best wishes”), yields أَسْتَغفِرُ اللهَ (astagfirullah) when rotated 90 degrees. Astagfirullah (Allah, forgive us our trespasses), expressing contrition, is recited when a person has sinned. In Turkish, this word is also used to refer to oneself in a self-deprecating manner, such as “I’m not worthy of such a compliment.” It is fascinating to see that kotobuki, used for felicitations, ends up meaning the opposite when the kanji is angled differently.

The kanji kotobuki, on the left, becomes the Arabic أَسْتَغفِرُ اللهَ when laid on its side. (© Nippon.com)

The work of Yamamoto, who often shows his unique combinations of Japanese and Arabic calligraphy at events or seminars he participates in and on his social media accounts, has been widely praised.

Mutual Understanding Through Calligraphy

What motivated Yamamoto to strike out into this creative area? “First of all,” he says, “I wanted to show the connections between the Islamic world and East Asia. Haji Noor Deen, a Chinese calligrapher, was the first to present these special calligraphy combinations to the world. Noor Deen is a member of the Hui people, a Chinese minority group who are adherents of Islam, but he is not especially well known in Turkey or the Middle East.”

Many people in the Islamic world only know the culture of their own milieu, Yamamoto explains. For example, Turkish people do not really understand the Islamic culture of the Middle East, and the reverse is also probably true of inhabitants of the Middle East: Muslims themselves are not aware of the cultural diversity within Islamic culture. Moreover, most people in Turkey and the Middle East are likely unaware of the rich Islamic culture of East Asia.

The same naturally holds true for the people of Japan, who are not so familiar with Islamic culture, Yamamoto says. “Many Japanese have little interest in religion, and even more so in the case of Islam. Some people picture Islam as ‘a religion of the desert,’ or may associate it with terrorism or jihad. But Muslims aren’t found just in the Middle East. There are Muslims in Africa, Turkey, South Asia, Malaysia, Indonesia, and even in China.”

Japan, he goes on, has been influenced by the culture of the Asian continent and in particular by Chinese culture, and therefore, art or crafts may be a way for people to develop an interest in each other’s cultures. “That’s what I had in mind when I encountered Noor Deen’s works. I felt that his calligraphy could provide an overture for Japan to be receptive to Islamic culture, in the same way that it’s been accepted in China.”

Yamamoto Naoki, during an interview at the Nippon.com office. (© Nippon.com)

What are the themes and characteristics of Yamamoto’s work?

“It’s based on the fact that the Arabic world has calligraphy, and so do China and Japan. I want people to show interest in the cultural commonalities of calligraphy. I strive to give my works what I perceive as a Japanese feel, to better take advantage of my brushwork. I also added an illustration of a higanbana red spider lily to my tatematsuru work: Turkish and Egyptian youth know higanbana through anime as an inauspicious sign that a character is about to die.”

Indeed, Japanese manga—a popular form of content in the Islamic world—sometimes include a frame artfully showing a higanbana before a character dies, or at the end of the story. Notes Yamamoto, “Young people in the Arab world are so familiar with Japanese culture that they readily associate higanbana with death.”

On the other hand, he says, his work is an opportunity to teach Turkish and Middle Eastern youth more about Japanese culture. “I explain that in Buddhism, higan means the world of nirvana, and that it is a time of year when people pay their respects to ancestors. Higanbana is a flower that blooms around the time of the autumn higan period.”

Unfortunately, says Yamamoto, most Japanese don’t know that pop culture media such as anime and manga are the way in which Middle Eastern youth have become familiar with Japanese culture. “We should do more to encourage mutual understanding by making use of our rich cultural assets as a tool through which to communicate,” he argues.

Anime as a Learning Tool

As a student at Dōshisha University’s School of Theology, Yamamoto chose monotheistic religions as his research topic, and was particularly drawn to Islam. “I visited several Arab countries,” he recalls, “beginning with Egypt, and in Turkey, the first country where I studied as a foreign student, I had an experience that left a strong impression on me.

“One day, after the professor had left the classroom following a lecture on Islamic classics, the students hooked up a computer to the projector and began showing the anime Naruto. That was the first time I realized how deeply Japan’s pop culture had penetrated among young people. It simply stunned me.”

Why was this ninja coming-of-age story so popular? When Yamamoto showed surprise that his classmates were watching Naruto during a break, they said: “Well, it’s just a great story, so we’ve been watching it since we were kids,” As he admits, “The story contains many ethical lessons that share common elements with Islam. . . . American content can come across as a bit excessive in its political messages, but Naruto contains many beneficial influences.”

There are loads of young people in Turkey and the Middle East who just love the culture depicted in Japanese manga and anime, explains Yamamoto. Despite that, many Japanese view Islam as distant and difficult to comprehend and are at a loss to find opportunities to initiate dialog with people from the Islamic world.

Yamamoto participating in an event introducing Japanese culture in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Hoping to stimulate interest in Japan, Yamamoto wears kimono whenever possible. (Courtesy Yamamoto Naoki)

As Yamamoto explains, Japanese anime are popular in part due to the influence of Spacetoon, a satellite broadcasting service targeting children. In the Arab world, children grow up watching anime such as Naruto, Dragon Ball, Captain Tsubasa, and Detective Conan. Earlier, in the 1980s, the UFO robot anime UFO Robot Grendizer was a major hit that was even more popular there than in Japan.

And anime are popular for more than just their entertainment value. “Although they may be exaggerating a bit, I’ve met lots of people boasting that they watched Grendizer to practice listening to standard Arabic, which can differ considerably from the language spoken in various parts of that region.”

But Japanese is also a part of the draw of these programs, Yamamoto notes. “In Turkey, where I live, most students who love anime know Kakashi Sensei, Naruto’s mentor, and they often use the word sensei—meaning teacher, or mentor—in daily conversation.

“Here there’s also a cultural aspect that shouldn’t be overlooked. In contemporary Western society, the relationship between master and student, where the student learns and matures while respecting the master, has weakened. But in the Muslim world this connection is still important. It’s also an essential element of the training process in Sufism, a mystical tradition in Islam, which is my field of study. I believe it’s exactly because of this cultural affinity that Muslim youth can become so wrapped up in Naruto, which depicts the strong bonds between Naruto and his mentor.”

A 2013 study session in Jordan, with students sitting in a circle around a renowned Islamic scholar, as is done traditionally. (© Yamamoto Naoki)

Knowing One’s Own Culture to Understand Others

Yamamoto looks to more than calligraphy for elements of Japan’s traditional culture that he can communicate to the Arab world. “I’ve been learning sadō, the way of tea, for many years. The thought came to me, when admiring tea ceremony utensils, that it would be really cool to design Japanese crafts inspired by Arabic script or Islamic culture. I spoke about my idea with a Kyoto lacquerware artisan, who created natsume, as containers for matcha are called.”

Lacquered natsume decorated with Arabic script. These objects drew considerable attention at exhibitions in Saudi Arabia and other parts of the Middle East. (© Nippon.com)

Some people may find it strange to incorporate Arabic script into a traditional Japanese craft, but kanji, after all, came to Japan from China. As Yamamoto says, “This demonstrates how, over time, Japanese culture has incorporated elements of both native and foreign beauty to create a multilayered culture. I think this is something that could be said of many cultures.”

Cultural exchange, says Yamamoto, is something that goes beyond religion or national or regional boundaries. “I believe that Japanese people should pay more attention to the Arab world. That world may feel unfamiliar, but after all, coffee culture, so well established in Japan, comes from the Arab world. Japanese should also know that many young Muslims want to know more about Japan.

“Anime, manga and Japan’s traditional crafts can be powerful tools for communication. Used well, they can help reaffirm and further broaden the appeal of Japanese culture. And in the process of doing so, I hope that Japanese people will awaken to the Arab world and to the wonderful depth and breadth of Islamic civilization.”

Yamamoto pairs Japan’s traditional hemp leaf motif with the word futuwwa in Arabic on a tenugui cotton towel, along with a motif showing the leaves of the futuwwa tree—whose name can mean “youthfulness” and, by extension, “chivalry.” (© Nippon.com)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Yamamoto Naoki shows his work fusing Japanese and Arabic calligraphy. © Nippon.com.)