Haga Hideo: Legendary Folklore Photographer

Images Culture Guide to Japan Travel History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Mentors’ Influence

(© Haga Library)

The field of Japanese folklore studies, established by Yanagita Kunio (1875–1962) and Orikuchi Shinobu (1887–1953), examines how the Japanese lived their lives and how their customs and culture took root and developed. Folklore research involves not only field studies and perusal of documents but also photographs taken by professionals, which can provide important documentary evidence through a visual record of folk rituals and ceremonies. Photos of traditional events that have died out, in particular, are immensely valuable. Haga Hideo was a preeminent folklore photographer whose legacy in this respect is incalculable.

Haga, born in 1921 in Dalian, northeastern China, came to Japan in 1939 to attend the university preparatory course at Keiō University. He already had a deep interest in photography by then, and joined Keiō’s camera club. Entering the school’s Chinese literature department, Haga’s strong interest in folklore studies was influenced by professor Orikuchi Shinobu, whose classes he attended.

Haga began his career as a professional photographer in earnest in the 1950s. The company where he was employed having disbanded, he was forced to decide whether to seek new employment or to pursue photography seriously. Heeding the advice of Okuno Shintarō (1899–1968), a scholar of Chinese literature and his mentor during university days, he decided to photograph traditional events and folk entertainment. As part of a comprehensive study project supported by a federation of nine academic disciplines, between 1955 and 1957 he spent 182 days on Amami-Ōshima photographing local folklore practices.

Recording for Posterity

Coincidentally, around this time, the Heibonsha publishing company was preparing to produce two series related to folklore, one a five-volume compendium of folk vocabulary and the other a 13-volume encyclopedia tracing the development of Japanese folklore studies. Haga supplied the photographs for these books, which gave him a steady source of income and set the course for his career as a photographer of folklore.

With this work under his belt, Haga published his first photo collection, titled Tanokami: Nihon no inasaku girei (Deity of the Rice Paddies: The Rice Cultivation Rituals of Japan) in 1959. This book records seven rituals and ceremonies connected with rice cultivation practiced in the prefectures of Fukushima, Aichi, and Hiroshima, as well as in Amami-Ōshima and other parts of Kagoshima Prefecture. Haga photographed these activities during the 1950s, at a time when modernization was rapidly changing traditional village life. He was no doubt motivated by the feeling that this dying way of life should be recorded, and his photographs reflect this sentiment.

Aenokoto, a Noto Peninsula ritual conducted yearly in early December. Here a family offers thanks for the year’s rice harvest by presenting food and a bale of rice to the rice paddy deity. Although the deity is invisible, it is feted as though it were an actual physical presence. Ishikawa Prefecture, 1954. (© Haga Hideo)

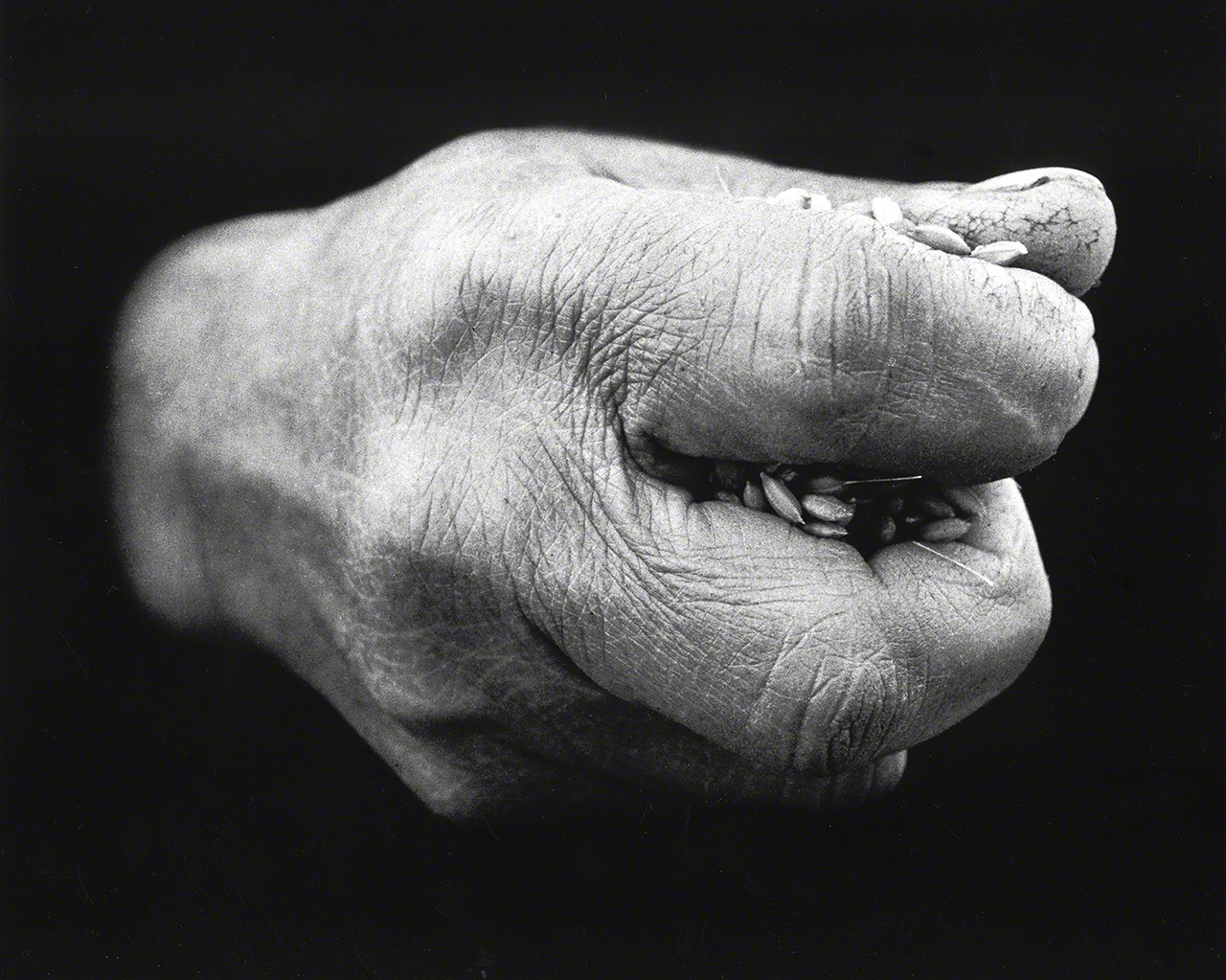

The tanemaki iwai seed scattering ceremony. A man’s hand grasping unhulled rice is photographed against a black background, giving the impression that the hand is floating. Aichi Prefecture, 1956. (© Haga Hideo)

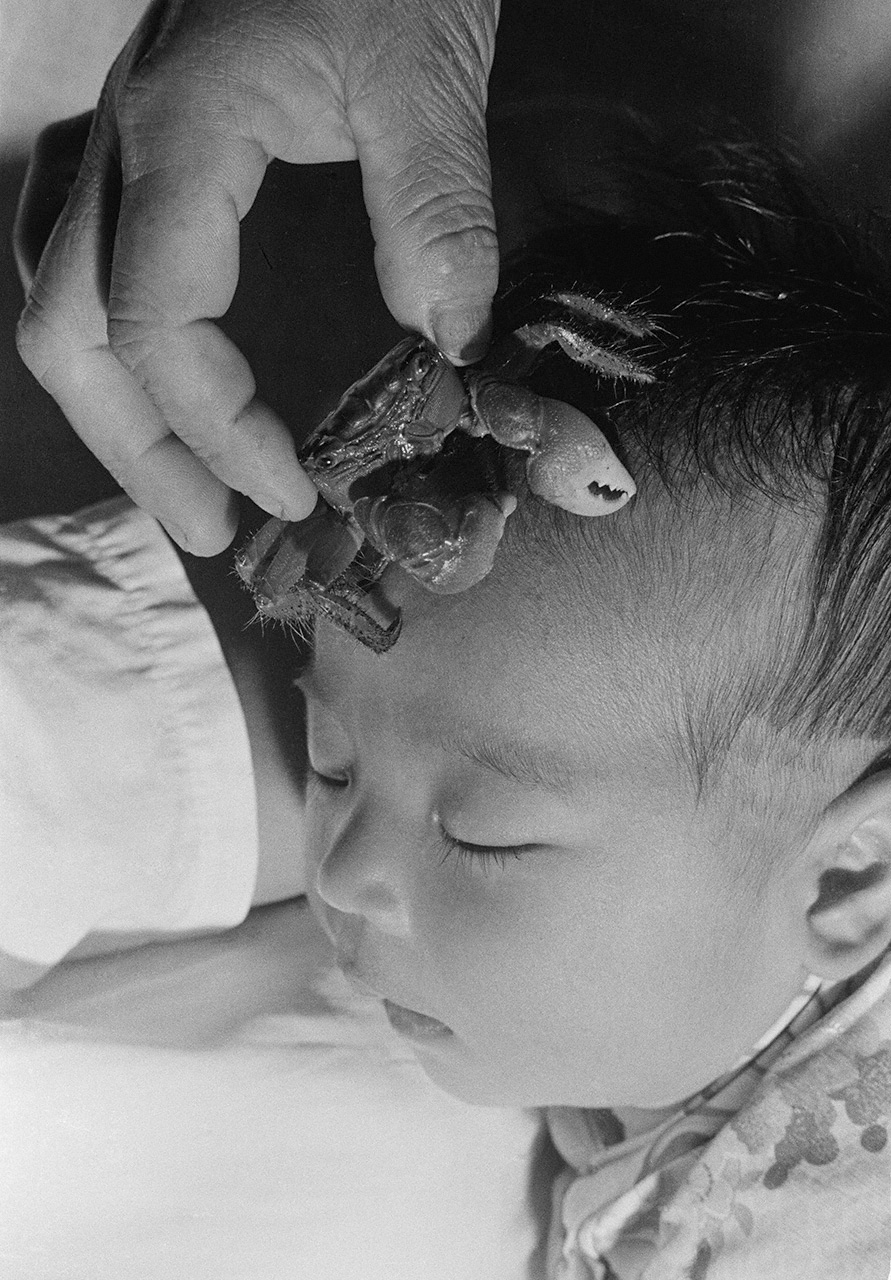

Nanoka iwai: A crab is placed on a seven-day-old baby’s head. The ceremony expresses the wish that the child will make it to the next stage of early life, crawling like a crab. Okinoerabujima, Kagoshima Prefecture, 1956. (© Haga Hideo)

Zujō unpan: Carrying a load on the head was a common sight in Japan’s southern islands. Here, the woman on the left is carrying cycad leaves to use as fuel. Kagoshima Prefecture, 1956. (© Haga Hideo)

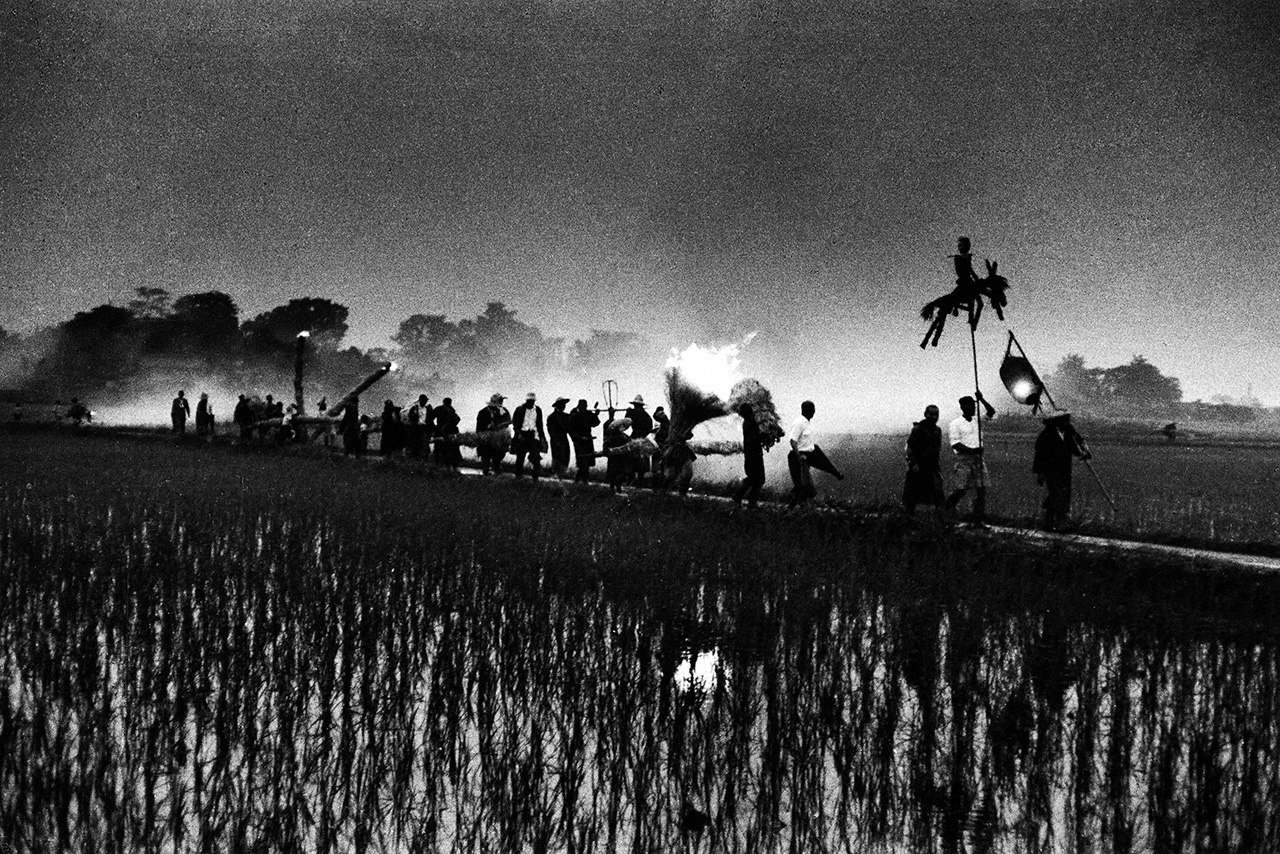

Mushiokuri: A phantasmagorical scene of people walking along a rice paddy footpath at dusk, with a straw effigy at the head of the procession. Aichi Prefecture, 1957. (© Haga Hideo)

As Haga continued to record folk rituals and ceremonies like those featured in his initial collection, he began exploring how best to photograph them. He intuited that simply capturing the scenes on film might fail to show the most important elements of the ceremonies, from preparations to participants’ movements, but that overly elaborate staging would detract from the subjects’ everyday vitality. He reached the conclusion that a “less is more” approach would produce the effects he desired. In a text he wrote on photographing the rice paddy deity, he described this approach as “eliminating every distraction or accidental intrusion on the scene to allow its essence to shine through”. As a result, the precious moments captured by Haga’s photos have retained their freshness over the years.

Moved by a sense of mission after the publication of his first photo collection, Haga traveled to every corner of Japan to photograph everyday people and their ceremonies.

Shima ni kaeru: An aerial shot of a small boat plying the route between two islands in the Gotō Island chain. The sea that day was calm, but rough weather could interrupt transport. Nagasaki Prefecture, 1962. (© Haga Hideo)

An ama female free diver, with a rope around her waist holding the tool she will use to harvest shellfish. She lightly taps the gunwale as a prayer for safety before diving in. Ishikawa Prefecture, 1962. (© Haga Hideo)

A Stupendous Photo Collection

Beginning in the late 1960s, Haga branched out into photographing in other countries in addition to Japan. At Expo ’70, the world exposition held in Osaka in 1970, he served as producer of the “Festivals of the World, Festivals of Japan” attractions at the site’s Festival Plaza, which no doubt broadened his interest in other countries’ folklore too. His photography travels took him far and wide, and to house his work, he founded the Haga Library in 1985. The Library’s collection initially comprised 300,000 photos from over 70 countries, with works by other photographers sharing similar ambitions added later. Today, the Library is one of the world’s preeminent folklore photo libraries, with over 400,000 photos in its collection.

Haga published numerous photo collections, more than 70 in all, over his career. Nihon no minzoku (Japan’s Folklore), published in 1997, is a two-volume collection of his most representative works. Shashin minzokugaku: Tōzai no kamigami (Folklore Studies in Photographs: Deities of East and West), appearing in 2017 when he was 95 years old, is a fine exploration of folklore studies, evidence of his passion for the subject and a testament to the incomparable depth and breadth of the photographic library he assembled and nurtured.

Sakaki oni: The Hana Matsuri, which takes place in northern Aichi Prefecture annually from November to January, climaxes with the appearance of the sakaki oni ogre. Wearing the ogre mask, the performer embodies the deity and acquires the endurance needed to swing a massive ax throughout the ceremony. Aichi Prefecture, 1972. (© Haga Hideo)

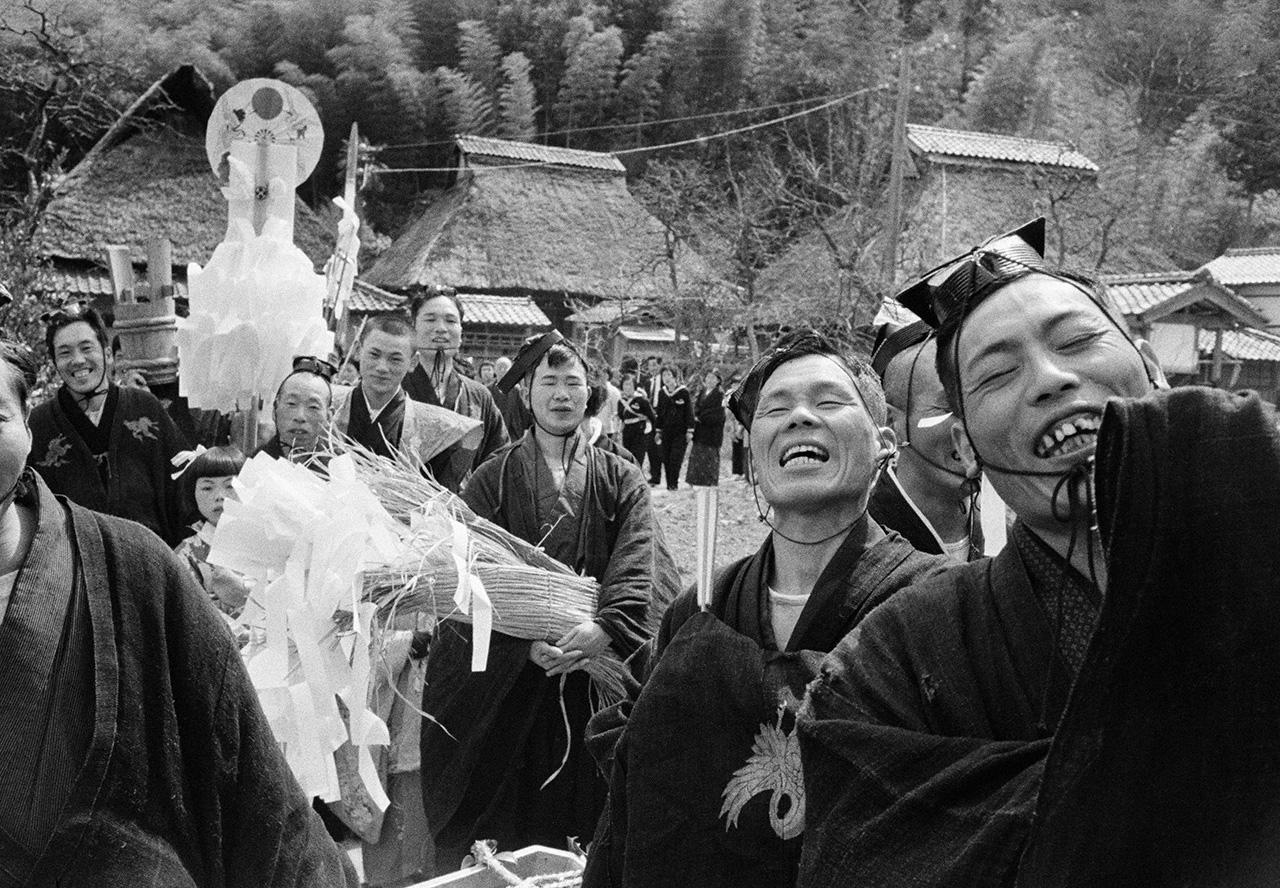

Muradachi: A scene from Kunitsu Shrine, a local shrine festival. After a festive meal hosted by the lead parishioner, merry worshipers carry a gohei pole decorated with paper streamers back to the shrine. Fukui Prefecture, 1973. (© Haga Hideo)

Ennen no mai: This photo, taken from an unusual perspective, depicts the dynamic movement of the ennen no mai, a ritual longevity dance performed at the temple Mōtsūji in Hiraizumi every year on January 20. Iwate Prefecture, 1979. (© Haga Hideo)

Saidaiji eyō: The yearly February eyō ritual of the temple Saidaiji is known for its hadaka “naked” festival. The energy of the naked men grappling to get hold of the shingi sacred amulet comes through well in this photo. Okayama Prefecture, 1979. (© Haga Hideo)

Mayunganashi: The mayunganashi rite in Ishigakijima. Villagers offer delicacies to the deities, which visit from Nirai, the land of the gods. This photo captures the intimate bond between the deities and their hosts. Okinawa Prefecture, 1988. (© Haga Hideo)

Hibuse no tsukai: Clad in straw costumes, men beginning a yakudoshi unlucky year carry gohei poles decorated with paper streamers. Emitting strange cries as they parade through the streets spraying water, they act as messengers of the deity. Miyagi Prefecture, 1996. (© Haga Hideo)

Masterpieces of Folklore Photography Leave a Precious Legacy

Haga passed away in 2022 at the age of 101. Although dependent on a wheelchair in his later years, he never lost his passion for photography. His photo library is now managed by his son Hinata. Working together with Nippon.com, Hinata has assumed the task of converting his father’s original film material into digital format and disseminating the library’s content internationally to make his prodigious undertaking more widely known. While excellent art photos do not necessarily make documentary photos of the same caliber, fine documentary photos are veritable art. How best to utilize this legacy is an issue for the future: Communicating this treasure trove of folklore photography masterpieces to future generations will no doubt have more impact than we can imagine.

Jūsan iwai: The jūsan iwai takes place once a girl reaches the age of 13 according to the traditional count and is the one and only ceremony that will ever be conducted in her family home. This girl, dressed in a sumptuous new kimono, wears a tense expression that reflects the importance of the occasion. Okinoerabujima, Kagoshima Prefecture, 1957. (© Haga Hideo)

A film negative strip taken at the jūsan iwai. The photo sequence is a precious record of how the girl comported herself during the photo session. (© Haga Hideo)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: The yūkui ceremony on Iriomote Island features a visit from the deity Miroku. Wearing a mask of Hotei, one of the seven “lucky gods,” and holding a gunbai war fan in its right hand, the deity is followed by a band of singers and musicians. Okinawa Prefecture, 1988. © Haga Hideo.)