Kazuo Ishiguro, Memory, and Japan

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

In March 2015, Kazuo Ishiguro once again came under the spotlight as he published his first new novel for a decade, The Buried Giant. Born in Nagasaki but brought up in England, the writer has been influenced by his Japanese background in various ways through his career, though sometimes in an indirect manner.

An Emotional Tie

Growing up, Kazuo Ishiguro’s image of Japan was shaped by “very distorted, very colored memories” of his early childhood. Born in Nagasaki in 1954, he moved to Guildford in England at the age of five when his father got a job working for the British government. He did not return to Japan until 1989, the same year that his third novel, The Remains of the Day, was awarded the Booker Prize.

But this 30-year sojourn in Britain was not the original plan. As he explained to Ōe Kenzaburō in a conversation during that 1989 visit, his parents always expected to go back to Japan, preparing him to do so with a steady diet of books and magazines from the home country. While he did develop a strong emotional tie to that land, in his early twenties he reconsidered its nature: “I realized that this Japan, which was very precious to me, actually existed only in my own imagination.”

At first, Ishiguro set out to recreate his personal Japan in his novels. His debut work, A Pale View of Hills, is set partly in Nagasaki and partly in England. His second, An Artist of the Floating World, is his only book set entirely in Japan. It tells the story of a painter named Ono who has lost his standing in the postwar era due to his former support for the wartime regime.

Clear influences from the films of Ozu Yasujirō supplement Ishiguro’s memories in this second book. Like the youngsters in Ozu’s films from the same era, Ono’s grandson is enthralled by American pop culture. And the difficulties finding a marriage partner for Ono’s daughter Noriko are reminiscent of the master’s films Late Spring and Early Summer, which center on attempts to find husbands for unrelated characters called Noriko, both played by Hara Setsuko. Underlining this source of inspiration, Ono’s other daughter is named Setsuko.

At the same time, Ishiguro’s exploration of questions of guilt and memory takes the book away from the gentle drama of Ozu territory into what has become a recurring preoccupation for the novelist. Among his various misdeeds, the painter Ono recalls denouncing his star pupil to the feared war-era police. Implausibly, though, he suggests that he had thought the authorities would just give him a stern lecture. The unreliability of memory helps Ono to misremember the extent of his wartime responsibility.

Displaced “Orphans”

Ishiguro’s subsequent novels have had largely European settings, but When We Were Orphans includes parts set in the International Settlement in Shanghai, both before the war and during the 1937 Japanese invasion. There are tantalizing biographical connections, as Ishiguro’s grandfather lived in the settlement and his father was born there. Yet, although richly evocative, the Shanghai of the novel is not intended as a literal depiction of the Chinese city.

The main character, Christopher, grows up in the International Settlement; his best friend is a Japanese boy called Akira. When he returns as an adult, he confuses a captive soldier he encounters with his boyhood friend and returns him to Japanese lines. In this way, although a minor focus compared with that seen in An Artist of the Floating World, Ishiguro once again examines Japan’s wartime history.

More than Japanese aggression though, it is British colonialism and support of the opium trade that come under Ishiguro’s microscope. Just as Akira is a kind of mirror for Christopher, displaced in Shanghai from his cultural heritage, the violence of the Japanese attack is a counterpoint to the destructive effects of corrupt British practices in China. Meanwhile, Japan itself is off-stage throughout, represented as an ideal lost home for Akira and the soldier.

History Issues

Ishiguro’s most recent novel, The Buried Giant, is set in a post-Arthurian fantasy version of England. It takes on forgotten crimes through the allegory of a dragon, which breathes out mist to cloud the memories of the people. As a recent interview indicates, alongside his focus on the United States, Britain, and other countries with their own dark past events, Ishiguro was also concerned by Japan’s history issues.

“In Japan—and I’m very distant from Japan, so I’m looking at this from a great distance—but there has always been this conflict with China and Southeast Asia about the history of the Second World War. The Japanese have decided to forget that they were aggressors and all the things that the Japanese Imperial Army did in China and Southeast Asia in those years.”

Although Ishiguro has moved away from early efforts to reproduce his personal version of Japan in fiction, his roots remain an important, if indirect, influence on his work. And it will be interesting to observe the latest interactions between Ishiguro and the country of his birth when he makes another trip to Japan in early June this year to promote his latest book.

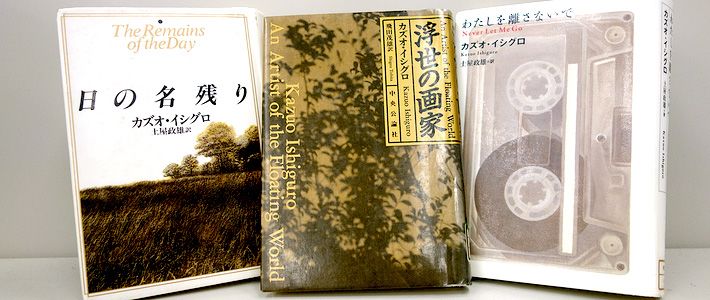

(Banner photo: Ishiguro’s works are popular in Japanese translation as well. Interview photo courtesy Robert Sharp/English PEN.)