“Our Mission Is to Live Our Lives”: A Deafblind Professor on the Meaning and Value of Life

Cinema Health Education- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Fukushima Satoshi is a professor at the University of Tokyo, the most prestigious institution of learning in Japan. But his road to get here has been toweringly difficult, due to the fact that he lost both his hearing and his sight in his youth. A film made about his early life, Sakura iro no kaze ga saku (A Mother’s Touch), has had a huge impact since it was released into theaters around the country in November 2022.

In this scene from the film, young Satoshi (Tanaka Taketo) and his mother Reiko (Koyuki) celebrate his admission to university despite losing his hearing as well as his eyesight. (© Therone/Karavan Pictures)

To mark the film’s release, we spoke to Fukushima about the lessons he has learned from his remarkable life.

Communicating as a Deafblind Person

I start by asking whether Fukushima ever takes steps to initiate a conversation himself. Unlike many people with congenital deafness, Fukushima was able to hear normally until he was 18. He has retained his “memory” of the language he heard before losing his hearing, and still speaks without difficulty.

“For communication to occur, it’s not enough just to speak,” he replies. “Unless you can hear what the other person is saying, it’s only one way. So except when it’s really necessary, I normally only speak when I am connected to my interpreter—in other words, when I’m in a position to understand what the other person is saying. There might be the occasional exception. I go to the lavatory on my own, so I might mumble the odd remark about the weather if it’s a cold day or something like that, but that’s about it.”

Professor Fukushima walks down the corridor of the University of Tokyo Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology. He is able to use the toilet unassisted. (© Hanai Tomoko)

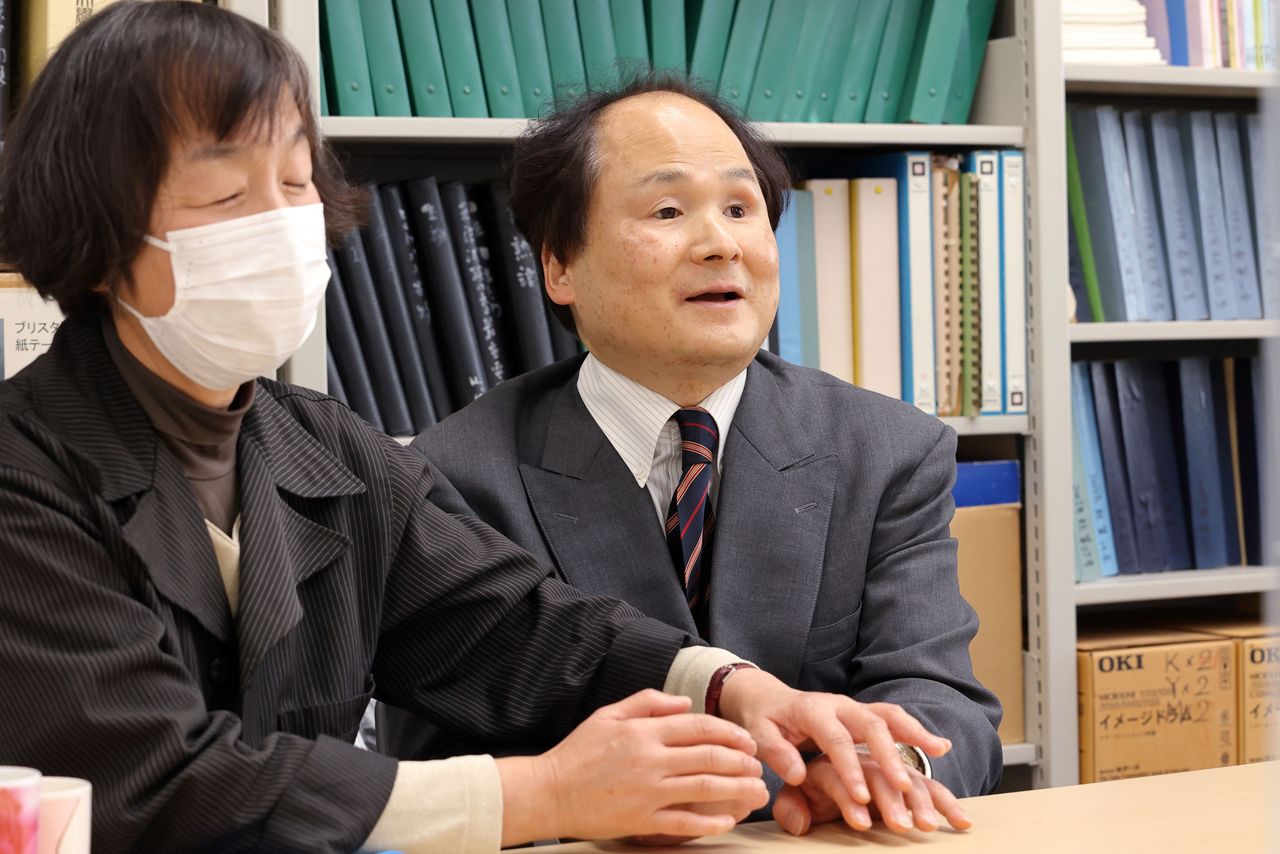

When you sit with Professor Fukushima, you realize that his reference to being “connected” to his interpreter is quite literally true. Having lost his eyesight and hearing, Fukushima relies on the sense of touch in his fingertips for communication. Sitting next to him is an interpreter who converts what people say into finger braille. She and Fukushima sit with their hands entwined, as the interpreter communicates sending messages by touch.

In finger braille, the interpreter taps messages using Japanese braille onto Fukushima’s fingertips in a manner similar to using a braille typewriter. As the film shows, this method of communication was invented by Fukushima’s mother, Reiko, more or less on the spur of the moment. Improvements have been made over the years, and finger braille has since spread as one of the methods used by deafblind people as a means of instant communication.

Fukushima’s finger braille interpreter Haruno Momoko taps his fingertips to allow him to understand what is being said. (© Hanai Tomoko)

With the help of his finger braille interpreter, conversation with Fukushima proceeds smoothly. The interviewer’s questions are transmitted to Fukushima in real-time by his interpreter, and the answer comes almost immediately in Fukushima’s own voice. The process has less delay than is common when using an interpreter between two different languages. The conversation proceeds so naturally that it is often hard to believe that the man in front of us lives in a world without light or sound.

Staying in Touch Through the Internet

As a university professor, reading is obviously an important part of Fukushima’s work. We asked him about the experience of reading in braille as a deafblind person.

“The most common form of writing for blind people in Japan uses a series of six dots to represent the sounds of Japanese syllables,” he explains. “When you read and write, you can also convert between the braille dots and kanji, and you can choose the specific character you want to use as well when necessary.”

Fukushima would have learned many kanji in elementary school before losing his sight, but there aren’t many that he remembers by their form. This poses little obstacle, though, he says.

“Even if I can’t visualize the shape of the characters, I know what they mean and the situations in which they are used. I have the big Kōjien dictionary loaded as text data on my computer, and that’s one of my favorite things to read. I’m always looking things up in that.”

What does it mean to read on his computer? Fukushima uses a special device that converts text data into Japanese braille. Using this device makes it possible for him to connect to the Internet and read the news online. He also uses the text output function on the device to type in braille, which is then converted into Japanese text, making it possible for him to write and send email messages.

Fukushima demonstrates the use of the BrailleSense mobile device used to input braille and collate information. The black pad at the front of the device allows him both to read and write using braille. (© Hanai Tomoko)

“Blind people can use the text-to-speech feature on smartphones and read books that way, but for those of us who are deaf as well as blind, that’s no use without output in braille. The device I use is called BrailleSense. As well as input and output in braille, it can connect to the Internet. I’ve installed data for about 7,000 braille books on this device. I’ve also converted about 1,000 more to text data, which I can read at any time via the braille output display.”

Fukushima demonstrates the use of his BrailleSense device by reading out the news from an online newspaper. Sitting to his left is finger braille interpreter Maeda Atsumi. (© Hanai Tomoko)

This kind of device was not available when Fukushima was younger, he notes. “It was in 1981 when I lost my hearing, following my eyesight. There was certainly nothing like this back then. The advance of this kind of technology has been a real blessing for people with disabilities. Even if you have restrictions on your physical movement, you can still connect with the world through the Internet. The device I use is extremely useful for me in terms of accessing information, but because the market for these devices is so small, they’re quite expensive. I was able to buy one using my research expenses, but most people who need these devices have to spend about 200,000 yen out of their own pockets, even with public support allowances. Living with a disability involves a lot of additional expenses like that.”

The Impossibility of Social Distancing

Using the device allows Fukushima to obtain information from around the world every day. I ask him about the issues that interest him most at the moment.

“Dirty bombs. The depreciation of the yen, to a lesser extent—so long as we can continue to make a living, it doesn’t bother me too much. I’m more worried that Russia might be tempted to use tactical nuclear weapons. If that happened, it would have an impact on Japan too on many levels. So, the war in Ukraine, and the possibility that Russia might escalate the situation and use tactical nuclear weapons, with a dirty bomb being one stage along that journey. I suppose those are the things that worry me most.”

Closer to home, I note, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a misery for the past few years—and the early stages in particular, when there was so little information, were worrying times for everyone.

“We cannot communicate without physical touch,” he notes, “so for us it’s impossible to avoid at least two of the so-called three Cs that people were urged to avoid to reduce their risk of infection. Telling us to avoid close contact and closed spaces was tantamount to telling us not to speak. That was the biggest concern for deafblind people. There was a big increase in the number of people who were essentially trapped alone at home. It was a very difficult period. And wearing a mask feels like being stifled with a big bag over your head. When you can’t see or hear, having a mask obscure your sense of smell too is hard. It’s almost like being suffocated.”

Overcoming Isolation

The problem of communication has been a concern on many levels during the pandemic. As someone who is in daily contact with students, I ask him whether anything struck him in particular in this area.

“I worry that many students are quite isolated—particularly the cohort who began their studies in the spring of 2020, who are in their junior year now. For two years after they entered the university almost all tuition was done online, and severe restrictions were placed on socializing and extracurricular activities. I think for many people it was hard to feel that they were really at university.”

The ubiquity of the smartphone has been one big change since he was a student, but he notes that this technology cannot close all the gaps opened by the pandemic. “You’re not sharing the same space on a phone. People need to spend time together, walking, eating, drinking . . . not being able to do these things leads to loneliness and isolation. Laughing and sharing a joke, physical contact—these little moments of togetherness are an important support.”

On the topic of togetherness, I note that he was 18 when he lost his hearing in addition to his eyesight. He has described the isolation he felt then as like being hurled alone into outer space.

“In space, there’s no brightness unless there is something for light to reflect off. Otherwise, it’s totally dark. I felt my situation was similar. You need some response from the outside world. It’s only when you have a response from other people that you get a real sense that you are alive and emitting light yourself. It’s not something you feel as a concept, but materially, physically. So when that input was reduced to almost nothing, it was very difficult to process.”

Fukushima’s mother then, has always been a sympathetic and supportive figure in his life, but he has described feeling unable to confide even in her—perhaps not such an unusual thing for male children, particularly during adolescence. His mother apparently wrote in her diary, “I don’t know what Satoshi is thinking.”

When I put this to him, he replies: “I wasn’t trying to hide anything, particularly. I didn’t say anything because I didn’t think it would make any difference if I did. Communication had been cut off and I felt as though nothing I could do would make any difference. I had sunk so low I felt I had reached the bottom of the sea. In the film, Tanaka Taketo, the young actor who plays me, cries. But in fact, I never did. When life gets really hard, you can’t cry. It’s only in response to little things that you shed tears.”

One scene in the film depicts the moment when Satoshi’s mother, Reiko, is inspired to invent finger braille as a way of communicating with her son. (© Therone/Karavan Pictures)

How was he able to rise up again from that low, then?

“As I read and wrote, I spent time thinking about things. All I could really do was to think. I thought that if life had any meaning, then there must be a meaning to this suffering as well. Lots of people lose their lives suddenly to accidents or illness at a young age. I knew several people that had happened to. But I had been given the gift of life.”

He was being asked to live without the ability to see or hear, he reflects. “What did this mean? The only person I’d heard of in a similar situation was Helen Keller—but surely there had been other people like me in Japan too. The fact that they were not known was because society had never paid any attention to them. I started to sense that I was being sent a message, that I needed to do something to help these people.”

Our Mission Is to Live

Some people struggle to find a meaning in life and rush to drastic conclusions about its absence, but Fukushima urges perseverance. “If you say that life has no meaning, that’s the end of it, right there. If you think that human existence is meaningless, then everything loses its meaning. I think you have to believe that there is some kind of meaning to life, even if you can’t say exactly what it is. I think that’s what we’re called on to do—first of all, to live, and next, to go on living.”

Most people, I note, are unable to boil things down to this simple essence, and worry more about the details of how they should live.

“I think people try too hard to find their own genuine and unique way of living,” he says. “They end up achieving the opposite, living lives that are controlled and directed by superficial things. They worry about what other people think, they compare themselves to others, and they stress out about things that are not important. I’ve lived my life in the belief that comparing yourself with other people is meaningless.”

Fukushima says he was once asked by a journalist if he ever felt jealous of other people who live their lives without disabilities.

“As far as I remember, though, I never have. If I spent my time thinking, ‘This person can see, this person can hear,’ and feeling jealous of that, it would make my life impossible. I wouldn’t be able to go on living. Everyone is different. People have their lives, I have mine. That’s the basis on which I live my life. No one can live your life for you. You have to live it yourself.”

Some people, I note, say that they’d rather die than face being put in a tough position in their life.

“Even if you don’t have a disability,” comes his reply, “for many people there comes a time in life when their capabilities weaken and decline because of age or illness, and they can no longer live without depending on other people. Those who were active in their younger days are particularly likely to find themselves thinking that they’d be better off dead. But as babies, all of us started out being dependent on other people. If you reach old age and can’t do anything for yourself, that’s part of nature too. Some people can’t live without the help of others, and some people are there to help. We need both in the world, helping one another to fulfill our mission to live and stay alive. That’s the way it should be.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Finger braille interpreters: Haruno Momoko and Maeda Atsumi. Photos © Hanai Tomoko. Interview and article by Matsumoto Takuya, Nippon.com.)