Kita Toshiyuki: Designs for a Better Japan

Economy Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

INTERVIEWER You have worked in a number of countries around the world. Do approaches to design differ from country to country?

KITA TOSHIYUKI There’s a design boom underway in Asia at the moment. Countries are taking design seriously as a project of national importance. China in particular has announced its intention to develop design as a “new resource.” The government has set up specialist design departments in more than a thousand universities. Over 600,000 students are currently enrolled in design courses in China.

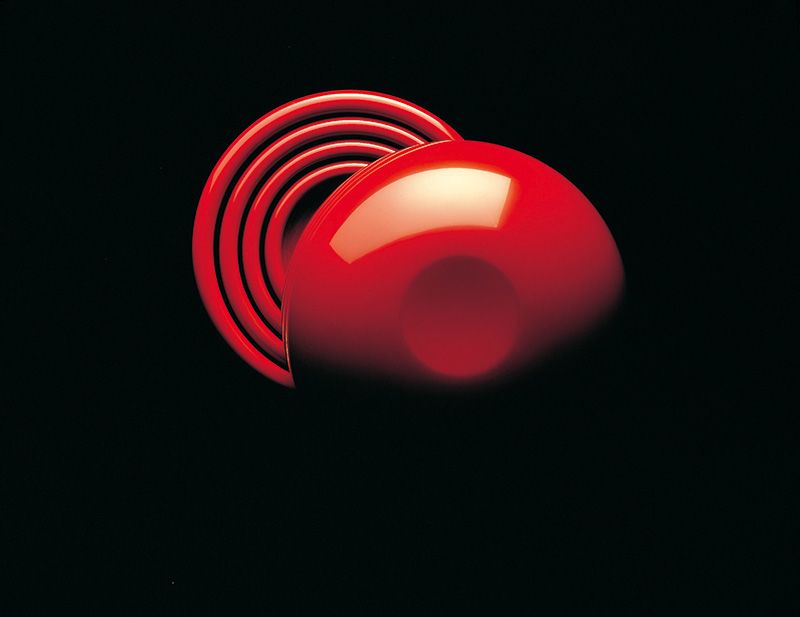

Aquos C1 / 2001

Aquos C1 / 2001

Sharp (Japan)

Photo: Luigi Sciuccati

Chinese companies that used to focus on contract-basis production are now working hard to build their own brands. Design is a big thing right now. The huge Chinese market is bringing a new energy to design. A similar kind of design fever can be seen in Korea, where major design centers have been built. Seoul has ambitions to become a hub city for design in the Far East. Throughout the region, the three elements of design, market, and the economy are coming together as one. There is a real sense of vibrancy and energy in the design movement across the booming economies of Asia.

Actually, even in Asia, concepts of what design involves can be quite different. In Chinese, for example, the word for “design” is sheji [設計]. This incorporates a much wider range of nuances than the loan word dezain in Japanese. It takes in all stages of the production process, including planning and engineering. The Italian term disegno has a similarly wide range of connotations. In Japan, though, dezain tends to be thought of much more narrowly. It’s often limited to the superficial, purely aesthetic aspects of a product. As a result, design departments in Japanese companies have a low profile and often lack clout. This is particularly true of the big companies.

INTERVIEWER Would you say that design in Japan faces a challenging environment today?

KITA I would. One of the purposes of design is to improve the places in which people live, work, and carry out their daily activities. Design should make these places more pleasant and more convenient. But the Japanese lifestyle has not improved in this respect for a long time. The fact that people’s homes tend to be so small is a major factor. People live in confined spaces that are so crammed with domestic appliances and furniture that they end up looking like storerooms. They don’t have the space to invite friends over for dinner, and therefore don’t have any incentive to collect or display beautiful objects. As a result, Japanese interior design and the furniture industry in particular are at death’s door. It’s certainly true that Japanese people have large savings, but in terms of everyday life, the sense of affluence is being whittled away at an astonishing rate. This is a warning signal for Japan.

KITA I would. One of the purposes of design is to improve the places in which people live, work, and carry out their daily activities. Design should make these places more pleasant and more convenient. But the Japanese lifestyle has not improved in this respect for a long time. The fact that people’s homes tend to be so small is a major factor. People live in confined spaces that are so crammed with domestic appliances and furniture that they end up looking like storerooms. They don’t have the space to invite friends over for dinner, and therefore don’t have any incentive to collect or display beautiful objects. As a result, Japanese interior design and the furniture industry in particular are at death’s door. It’s certainly true that Japanese people have large savings, but in terms of everyday life, the sense of affluence is being whittled away at an astonishing rate. This is a warning signal for Japan.

Design is something that grows naturally out of everyday life. The Japanese economy depends on exports. That means that we need to produce good things and export them to people in other countries. But I worry that with our current level of lifestyle, we may lose sight of what quality means.

Traditional Crafts: Revered Abroad, Neglected at Home

INTERVIEWER Italy has managed to maintain its position as a major center of design, despite its financial difficulties.

KITA Until recently, Italy didn’t even have a major design school. You could say that all Italian design in recent years emerged naturally from the patterns of daily life. In Italy, people’s homes are like salons: a place to welcome friends and entertain. They are places of exchange, where people come together. And this makes people want to decorate their homes with fine objects and beautiful things. People have a motivation for turning their homes into a stage for an attractive lifestyle. This is the soil that produces great design.

But in fact Japan used to have a similar culture of attractive lifestyles of its own. In the past, almost everything made in Japan was painstakingly designed. Traditional houses, for example, or lacquer bowls—design was an essential part of the objects that people used in their everyday lives. This sensibility reflected the natural environment to a wonderful extent too. Japan was remarkably successful in incorporating an environmental approach into all parts of the culture—including design.

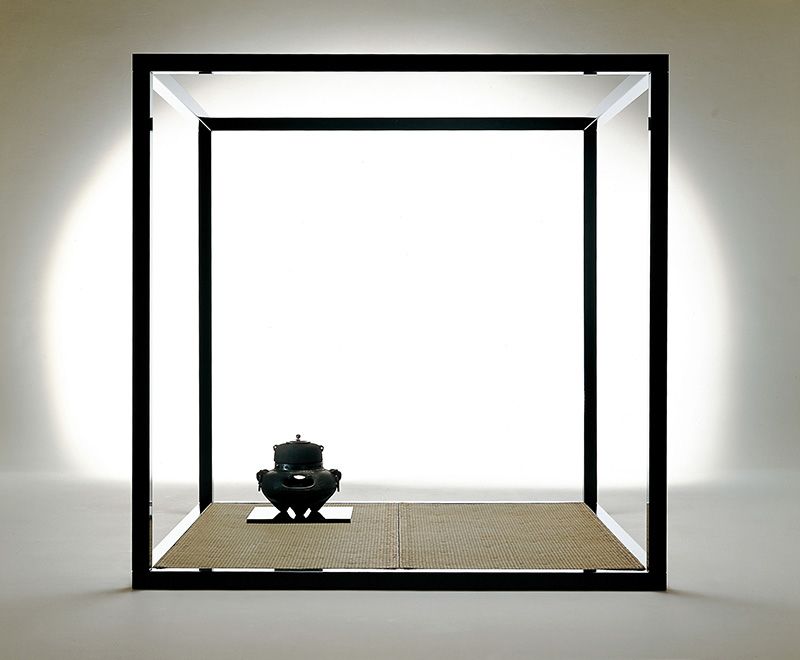

Wajima / 1986

Wajima / 1986

Ōmukai Kōshūdō (Japan)

Photo: Nob Fukuda

Japan’s traditional craft industries enjoy a high reputation all over the world, but in Japan itself they are on the brink of extinction. The decline in living standards, brought about by the cramped living quarters, is to blame.

About forty years ago, desperate to do whatever I could to halt the decline of the traditional industries, I started approaching craftsmen in different regions around Japan, proposing that we collaborate on a project. But it didn’t pan out the way I hoped. We tried making things, but the market didn’t materialize. There were simply not enough people looking to incorporate good-quality, traditionally made objects into their lives. I racked my brains trying to figure out why the traditional industries were in decline, but in the end I realized the answer was simple: no market. Basically, I think we need to start enjoying life more. That’s the first step to reinvigorating Japanese design and the traditional industries that support it.

Better Designs for Better Living

INTERVIEWER What are the prospects for rebuilding a better way of living in Japan?

KITA I’m confident that the future is bright for Japan. The economy has slumped so badly that if there is no sign of recovery soon, a change of lifestyles will be the only way to bring about economic growth. There will simply be no alternative. If people’s lifestyles improve, there will be an increase in domestic demand. And that will lead to economic recovery. The housing situation can’t get any worse. Because the industry has been so neglected for so long, there’s plenty of room for growth.

A good first step would be to try to use renovations as a way to increase the cramped size of Japanese housing. Invest some of your savings in renovating your home, and a dream lifestyle could be waiting for you . . . Countries like Germany and Italy tried this with some success about forty years ago. In Korea, too, there’s a movement to establish minimum housing standards to guarantee larger living spaces.

Kita relaxes on the Saruyama chair, one of his trademark pieces. He says he got the idea for the relaxing, freeform chair (whose name means “monkey mountain”) while watching monkeys on Mt. Takasaki in Ōita Prefecture. The prototype was produced more than 40 years ago, and the product has been a favorite around the world since 1990.

Kita relaxes on the Saruyama chair, one of his trademark pieces. He says he got the idea for the relaxing, freeform chair (whose name means “monkey mountain”) while watching monkeys on Mt. Takasaki in Ōita Prefecture. The prototype was produced more than 40 years ago, and the product has been a favorite around the world since 1990.

I am confident that if we used renovation to increase living spaces in Japan in a similar way, the situation would improve quite rapidly. If people are not living a richer, more affluent lifestyle in Japan today, it is not because we can’t do it. It’s more a question of desire than anything else.

Japan already has a rich foundation for design and plenty of skilled workers, so once lifestyles start to change, we would probably see dramatic improvements. It’s quite simple—people have to make a conscious decision to enjoy their lives more. After all, you only live once. If we can achieve that, everything else will follow.

INTERVIEWER The idea of living life to the full is deeply imbedded in the local culture of your hometown of Osaka, isn’t it?

KITA That’s right. Historically, Osaka culture has had something slightly Latin about it. It’s also a culture where people have not been afraid to speak their minds. In that sense, it’s possible that the movement to reassess the way we live our lives might start there. There are big political changes underway in the city at the moment too. I’m hopeful that there is the potential for change.

Craftsmanship with Heart and Soul

INTERVIEWER When did you first become interested in design?

KITA At quite a young age. I suppose I would have been in junior high school. At the time, “design” was a new term in Japan. I was intrigued to know what it meant. It had this image as a new profession that had sprung into existence since the war. To my childish way of thinking, it seemed to offer a front-row view of the latest developments. I think that was the appeal at first—I wanted to be one of the first to see what was happening.

In some ways, a designer’s job is similar to that of a chef. You have to put your basic ingredients together in a way that will please as many people as possible. You need care and consideration. In design just as in cuisine, you have to make use of limited ingredients to produce an item that the user will enjoy using. Otherwise it has no value.

INTERVIEWER What kind of perspective do you think is necessary when trying to communicate an image of “Japan” to people in other countries?

KITA The first thing to remember is that Japan is blessed with rich and abundant natural beauty. You can enjoy the beauty of the four seasons anywhere you go in Japan. History and cultural heritage are also extremely valuable resources. In particular, I think there is something typically Japanese about the pride people take in craftsmanship—not in the object itself, so much as the state of mind during the process and the determination to create something really special.

This is true not only of the traditional crafts. It applies to modern high-tech products as well. This dedication—the sense that engineers and designers are really putting their heart and soul into the product—is something that applies to all made-in-Japan products. We must make sure that we pass this on to the future.

It may be this sense of heart and soul and the drive for perfection that makes Japanese design different from design in other countries. The Japanese economy is in the doldrums at the moment, but so long as this spirit and motivation survives, I think it’s only a matter of time before things burst into bloom again.

Today, young designers across Asia—in particular, embryonic young designers in places like China, Taiwan, and Korea—are using the Internet to keep up with designs from all around the world. In that sense, national borders are disappearing from the world of design. This is precisely why it is important for Japan to maintain its own sense of originality. This idea of heart and soul should be one of the defining keynotes of the Japanese approach to design.

(Translated from a December 14, 2011, interview in Japanese. Interviewer Harano Jōji is representative director of the Japan Echo Foundation. Photographs by Ōtaki Kaku, with thanks to the Japan Institute of Design Promotion.)

craftsmanship design Sharp Kita Toshiyuki product design traditional crafts Aquos Cassina Wink chair Wajima lacquer washi renovation ecological culture