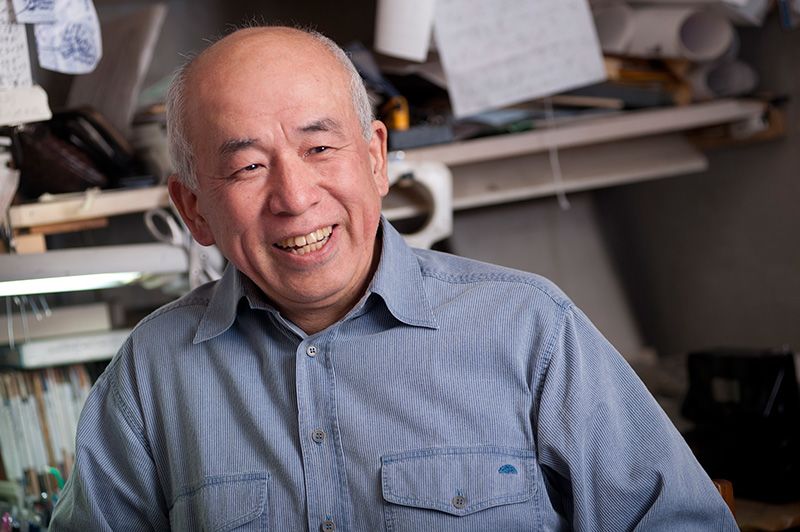

Leaving His Mark on an Ancient Art: Arabic Calligrapher Honda Kōichi

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

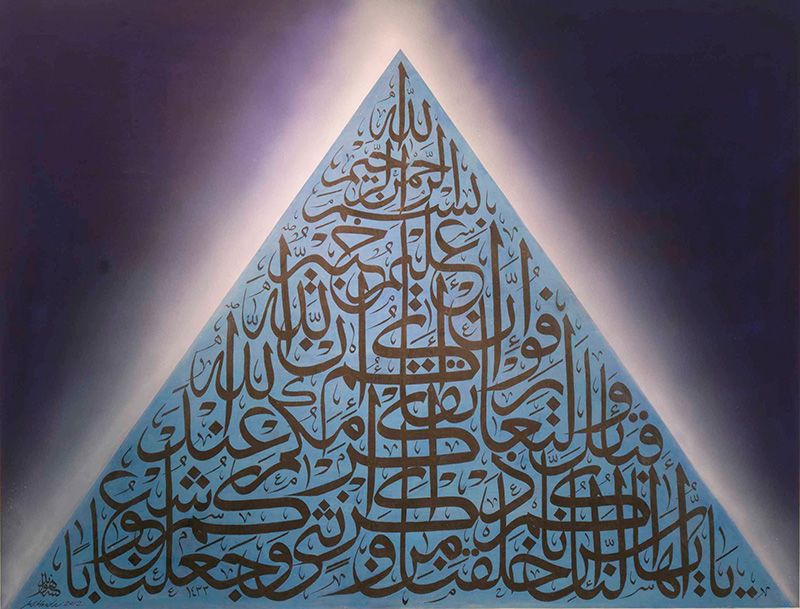

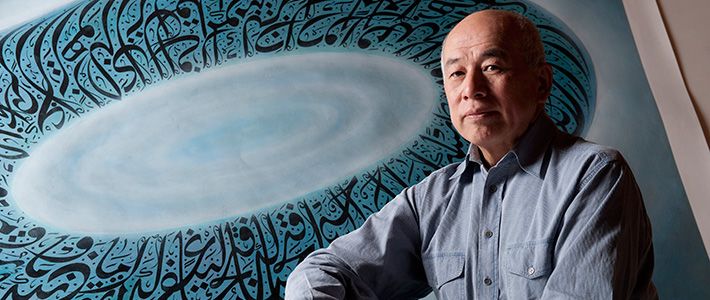

An image of a blue pyramid soars toward the heavens as white light emanates from its sides like an aura. A closer look reveals that the exquisite design on the surface of the pyramid is Arabic calligraphy: a passage from the Koran, inscribed from the lower right, with the word “Allah” at the pyramid’s apex. This work of art, titled “Prayer Pyramid,” is the creation of Honda Kōichi, a Japanese who has mastered the ancient art of Arabic calligraphy. His works have been displayed at such prestigious venues as the British Museum, reflecting the admiration he has won in the Islamic world and all around the globe for breathing new life into this ancient art. We interviewed Honda to learn more about the charms of Arabic calligraphy.

The Height of Artistic Perfection

INTERVIEWER When did you first encounter Arabic calligraphy?

HONDA KŌICHI I was working in Saudi Arabia and other Middle Eastern countries as an interpreter for a Japanese firm. Our company had been hired to create maps of the region, and I went there as part of its project team. We took aerial photographs of the region and conducted on-the-ground surveys, recording the names of riverbeds, hills, and other topographical features. We then took this information to the Saudi Ministry of Petroleum in Riyadh, where calligraphers wrote in the names that we had recorded. I was struck by how beautiful the Arabic characters they wrote were; even for a Japanese person like myself, the shapes were enthralling.

The supervisor accompanying us from the government ministry was also a calligrapher, so I asked him to teach me more about the art. He loaned me a book on the alphabet and a reed pen. I would copy down the characters and show them to him for corrections. The more I worked on this, the more interesting it became. Gradually I found myself completely absorbed in Arabic calligraphy.

INTERVIEWER What is it about Arabic writing that appeals to you?

HONDA Each character is perfectly balanced, with a natural sort of shape. The proportions of the characters are quite beautiful. Arabic calligraphy has a sort of musical rhythm. Even a person who doesn’t understand their meaning can pick up on the feeling that the characters convey.

There are basically eight different styles of Arabic calligraphy. The shape of each character is governed by strict rules. Originally, Arabic characters were developed in order to express the Koran. It took over a thousand years to perfect each line in order to beautifully write the words of God. If you examine the characters, you’ll find that the proportions between the various parts correspond to the “golden ratio.” Indeed, Pablo Picasso once said that the level of artistic mastery reflected in Arabic calligraphy is so advanced that he “would never have started to paint” had he first known of the tradition. Backed by the correspondence with that golden ratio, each line presents us with an example of artistic perfection.

The paper used for Arabic calligraphy has a slick surface.

The paper used for Arabic calligraphy has a slick surface.

The calligrapher first creates a draft for the design with the position of the characters and other elements. It can take months to complete a single work of calligraphy.

The calligrapher first creates a draft for the design with the position of the characters and other elements. It can take months to complete a single work of calligraphy.

The writing implements Honda uses, whittled from bamboo or reed to suit his purposes.

The writing implements Honda uses, whittled from bamboo or reed to suit his purposes.

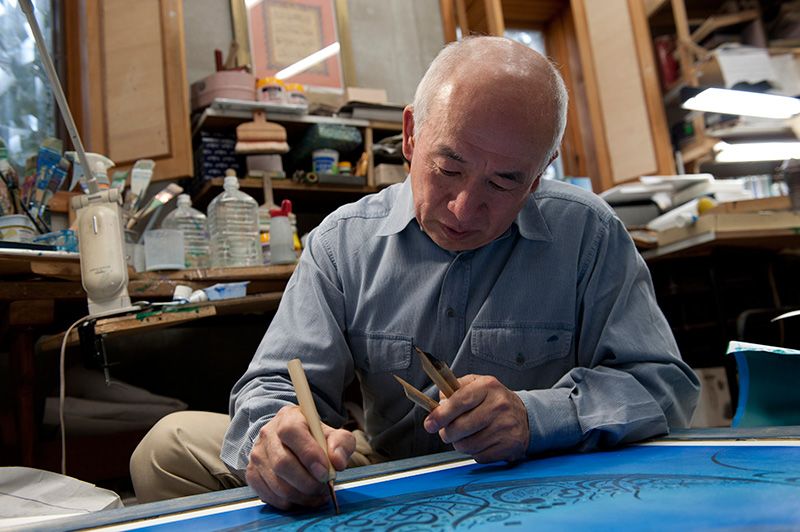

A view of Honda at work, making use of a variety of writing implements to draw lines of all sizes.

A view of Honda at work, making use of a variety of writing implements to draw lines of all sizes.

Characters Perfected Over a Millennium

INTERVIEWER How long does it take a person to master one of the eight styles of calligraphy?

HONDA It’s said that it usually takes around twenty years. In my case, back in 1988, I was invited to attend an Arabic calligraphy festival in Baghdad that brought together 188 calligraphers and scholars from around the world. At the time, I was beginning to be recognized as an Arabic calligrapher and was receiving requests for my work from corporations and embassies. I was skilled for a Japanese practicing the art and thought that I was drawing the characters perfectly, but the world-class calligraphers I met at the Baghdad event had some harsh criticism for me. They told me that to draw the characters without strictly adhering to the accepted rules was unacceptable.

HONDA It’s said that it usually takes around twenty years. In my case, back in 1988, I was invited to attend an Arabic calligraphy festival in Baghdad that brought together 188 calligraphers and scholars from around the world. At the time, I was beginning to be recognized as an Arabic calligrapher and was receiving requests for my work from corporations and embassies. I was skilled for a Japanese practicing the art and thought that I was drawing the characters perfectly, but the world-class calligraphers I met at the Baghdad event had some harsh criticism for me. They told me that to draw the characters without strictly adhering to the accepted rules was unacceptable.

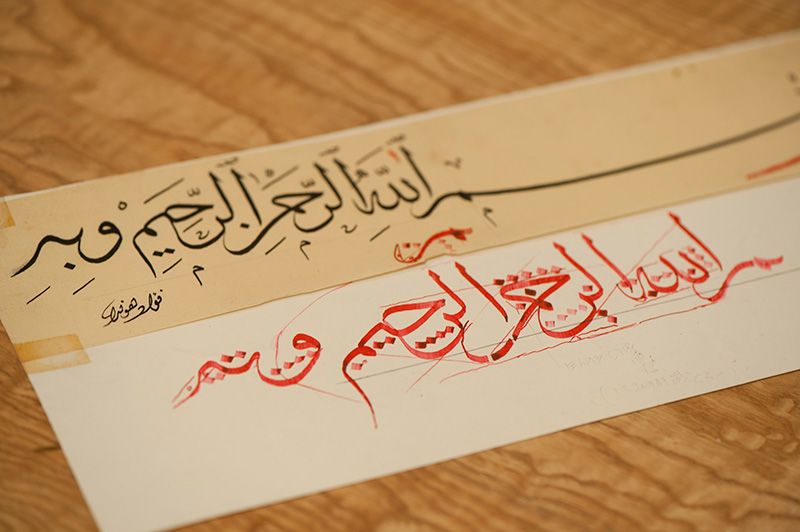

A line of calligraphy by Honda with Çelebi’s corrections below in red. The number of dots inside the characters indicates the shape of the curves.

A line of calligraphy by Honda with Çelebi’s corrections below in red. The number of dots inside the characters indicates the shape of the curves.

At the event I was introduced to the Turkish calligrapher Hasan Çelebi. I asked him to correct my work via airmail. At first, the characters I had drawn were covered by his corrections in red ink. It was only around ten years later, in 1998, that he finally wrote the word “Congratulations” to praise my work. And two years later, he presented me with the ijaza diploma certifying me as a master calligrapher.

Because the calligraphic lines were perfected over a millennium, drawing them takes a high level of technical skill that is passed on from teachers to their students. The Arabic characters drawn by master calligraphers will all have the same beauty. It’s a universal art that transcends ethnicity or nationality, which I think is a rarity among the world’s calligraphy. Perhaps the closest thing to Arabic calligraphy in the realm of art is music. Even though each musical note exists on its own, it is the way that they are strung together to create a piece of music and how that music is played that are the basis for stirring a person’s heart. This is the same as the case of Arabic calligraphy. Combining letters creates a sort of rhythm—a silent yet musical flow.

A Natural World that Sharpens the Senses

INTERVIEWER What is it that you hope to express through your calligraphy?

HONDA After I graduated from university, I spent around four years as something of a recluse, instead of entering the workforce; I had no idea of what path to take in life. Every day I spent reading the classics, like works of Socrates or Goethe; I listened to the music of Bach; I looked at paintings by Cezanne. Even though I couldn’t see the road ahead, I felt a sensibility awakening within me. I remember going to a theater at the outskirts of Tokyo and being overwhelmed by tears of emotion from seeing the beautiful movements of a woman dancing in the performance. It gave me the feeling that sculptors in Ancient Greece must have experienced at the sight of a woman’s beauty.

I’m looking to find answers to the most fundamental questions for me, such as: Why was I put on this planet? Where am I headed? I want to articulate my answers to those questions in a form that is uniquely mine. When I was in my mid-twenties I hadn’t yet built up the experience needed to create something of my own. But it was around that age that I came into contact, in the Middle East, with the Islamic culture and a natural landscape of a sort that is unimaginable in Japan. And it was then that I also encountered Arabic calligraphy.

When you read the Koran in Arabic, even as a Japanese person, there are expressions that you can grasp and many passages with a profound meaning. For example, there is the line: “Everything will perish save His [God’s] face.” In other words, phenomenally speaking, we all disappear at some point, but the God who created us is eternal. In that sense, as entities created by God, we have an eternal quality that extends beyond the level of physical existence. This is one of the essential precepts from the Koran that has inspired me.

Another thing that I found quite different in the Middle East was its natural landscape, which is so different from that of Japan. The colors you see in the desert are in fact quite rich in their variations, always changing as the light from the sun changes. As dawn nears, a silver light gradually spreads out, eventually becoming a deep ocean blue. When the sun first peeks over the horizon the light changes to a golden yellow—but just a moment later it’s completely white. The light then becomes so powerful that you can’t make out the contours in the land. When the sun begins to set in the evening, various colors appear again as the sky is tinged a fiery red. A few minutes later everything is pitch black, and the space above the horizon is the star-filled heavens no matter which way you turn. At night you can’t hear a single noise; it’s so quiet that it almost makes your ears ache. Living in this sort of natural world you’ll find that gradually all five of your senses are sharpened.

A work by Honda titled “Blue Desert.”

A work by Honda titled “Blue Desert.”

Try to imagine what a lightning storm in the desert is like. The shafts of lightning crash toward the ground, followed by the welcome rainfall. In the Koran the rain is seen as a joyful sign, bringing life to the people and serving as a visible symbol of a divine presence.

Living in the Middle East fundamentally altered my view of the world. It even made me feel that I had a mission to convey this experience to others. My time spent there remains a driving force for me today. But now, unlike when I was in my twenties, I have the medium of Arabic calligraphy with which to express myself. This has led one idea after another to well up in my mind. I write down each new idea in a notebook. I’ve already filled up eight of them, which is enough to last me the rest of my life.

INTERVIEWER Some have said that you’ve brought about a “revolution” in the art of Arabic calligraphy. What is it about your approach that sets you apart?

A work by Honda titled “Blue Ark.”

A work by Honda titled “Blue Ark.”

The characters drawn by Arabic calligraphers are embellished with decorations, but it was a practice that I had some doubts about. People in the Middle East like to fill in spaces with some arabesque or marbled pattern, whereas Japanese prefer to maintain that empty space and eliminate whatever is not strictly necessary. I thought that I would cut out the decorations too and concentrate on the lines of the Arabic characters. When I did that, it began to bring out—in a vibrant way—the shapes of the characters themselves.

Each of the eight calligraphy styles for Arabic has its own personality—some have a forceful, masculine quality, while others are characterized by a feminine grace. By creating a design that combines different styles and alters the colors and sizes, the calligrapher can achieve new forms of expression.

I pursue the most beautiful lines for the characters I draw while adhering completely to the rules set down for the art of Arabic calligraphy. That’s the key principle from which I will never sway. Other calligraphers have understood this stance and shown appreciation for my work—even praising the view of the world expressed in my works. All of this has been very gratifying to me.

(Translated from an interview in Japanese. Photographs by Kodera Kei. Assistance provided by the Japan Arabic Calligraphy Association.)

Egypt Koran Arabic Islam calligraphy Honda Koichi Ijaza Hasan Celebi