Tradition and Renovation in Kabuki: Matsumoto Kōshirō IX

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

An Unforgettable Start for the New Kabukiza

The newly rebuilt Kabukiza theater opened in April 2013 in Tokyo’s eastern Ginza district. The first three months of performances at the rebuilt center for this Japanese performing art were highlighted by the appearance of one of the stage’s brightest stars, Matsumoto Kōshirō IX, who joined the celebration with a lineup of popular plays featuring all-star casts.

“The Japanese economy is said to be turning up nowadays thanks to Abenomics,” states Kōshirō. “But I was thinking rather about the difficulties people have faced since the great earthquake in northern Japan in 2011, and I was just thankful that so many people came to the new theater to see kabuki.”

The actor notes that during the past three years performers have made efforts to put on kabuki shows in theaters around the country, but there is something special about the art’s “home” here in Tokyo. “The new Kabukiza has nice dressing rooms, and its backstage areas are more spacious and very convenient. The size of the stage is perfect, just the same as the previous theater. But the important thing is not the theater itself—it’s to maintain the quality of kabuki that is played inside. Kabukiza has a mission to present performances that will draw audiences from all over Japan and around the world.”

Kabuki is very much a family affair. In April, Kōshirō’s son, Ichikawa Somegorō VII, appeared in the very first show celebrating the opening of the rebuilt Kabukiza. His eight-year-old grandson, Matsumoto Kintarō IV, played an important role in Moritsuna jin’ya (Moritsuna’s Camp), a fictitious war chronicle based on the battle between Toyotomi Hideyori and Tokugawa Ieyasu. Kōshirō himself played Benkei in the celebrated play Kanjinchō, which wrapped up the day-long, three-part program.

“I was deeply moved to be able to take part in the opening program with my son and grandson. What was more, it was almost a miracle that my 1,100th performance as Benkei fell on the closing night, April 28. The three months of performances marking the reopening of the Kabukiza are something that I will never forget.”

Three Generations of Benkei Actors

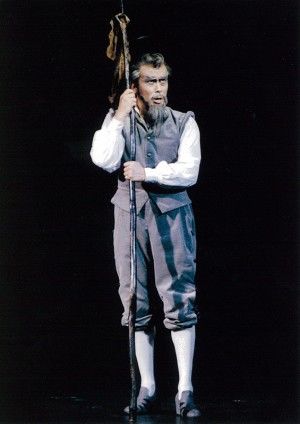

Kōshirō, playing Benkei at the Kabukiza in April 2013, performs his lively exit down the hanamichi to cap a performance of Kanjinchō. (Photo by Watanabe Fumio.)

Kōshirō, playing Benkei at the Kabukiza in April 2013, performs his lively exit down the hanamichi to cap a performance of Kanjinchō. (Photo by Watanabe Fumio.)

Kanjinchō, first played in 1840 by Ichikawa Danjūrō VII (1791–1859), is one of the kabuki jūhachiban, the 18 plays selected as the standard repertoire of the great actor’s house. The story takes place at the Ataka Gate, which is guarded by Togashi. Minamoto Yoshitsune and his servants, who are on the run from the authorities, try to pass the gate by disguising themselves as a troupe of Buddist monks soliciting contributions for the reconstruction of the temple Tōdaiji. Benkei, the main character of the play, faces Togashi’s tough interrogations but uses his wit and manages to clear the gate in the end. Kōshirō’s grandfather, Matsumoto Kōshirō VII (1870–1949), who learned the play from his master Ichikawa Danjūrō IX (1838–1903), traveled throughout Japan performing Benkei more than 1,600 times.

“Back then, Kanjinchō was not as popular as it is now. It was my grandfather who made it into a kabuki favorite. My father played it five to six hundred times, too, so my performances make it more than three thousand times in three generations altogether,” laughs Kōshirō.

“I’ve found the strength to continue playing Benkei to this day in the applause I receive from the audience. When I hear the big hand as I skip down the hanamichi—the runway passing through the audience—at the end of the show, it makes me forget all the exhaustion of playing the role. Kanjinchō embodies the devotion and passion of my grandfather, which my father inherited in turn. I hope to share it with as many as possible in order to pass on the play to the next generation.”

Benkei: How a Man Should Be

Kanjinchō features a realistic portrayal of the characters. As such it stands out from the other kabuki jūhachiban scripts, many of which are simple, even nonsensical plays.

Kōshirō describes one of the play’s dramatic high points. “When Togashi suspects that the porter in Benkei’s troupe is Yoshitsune in disguise, Benkei tricks Togashi by beating Yoshitsune with a staff. Hitting one’s master is an act of disrespect, so Benkei makes a slight bow in apology. This is probably one example of the subtle psychological elements that my grandfather made a part of the acting in kabuki plays.

“At the end of the play, Benkei leaves the stage last in line, after Yoshitsune and his servants. He has done all that must be done. He has also let his companions fulfill their duty. I see this as an ideal of how a man should act. These days we rarely find this kind of hero among Japanese men, but they still exist in the world of kabuki.”

Close Connections with the Western Stage

As Don Quixote, Kōshirō sings “The Impossible Dream” in a May 2002 performance of Man of La Mancha at the Hakataza theater.

As Don Quixote, Kōshirō sings “The Impossible Dream” in a May 2002 performance of Man of La Mancha at the Hakataza theater.

Aside from kabuki, Kōshirō has devoted his acting career to Western-style musicals. Most notable among his repertoire here is Man of La Mancha, a Tony-Award-winning musical based on Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote. Kōshirō first played the lead role in 1969 at Tokyo’s Imperial Theatre. The next year, he was invited to Broadway, where he gave 60 performances in English. On August 19, 2012, the day Kōshirō turned 70, he played Man of La Mancha for the 1,200th time. During the curtain call, the wife of the musical’s late author, Dale Wasserman, handed him the Tony Award trophy that Wasserman won in 1966.

Kōshirō was deeply moved. “I heard that Mr. Wasserman told his wife to give the trophy to someone who had contributed the most to Man of La Mancha. It was more than half a century since I first did the show, but I never felt as proud for doing musicals as I did that day. The trophy is now in my living room, right next to the fan I used in the thousandth performance of Kanjinchō at Tōdaiji.”

Kōshirō was 22 years old when he first took a shot at a musical. He played the King of Siam in The King and I with Koshiji Fubuki (1924–80), a renowned Japanese musical star. Back then, Kōshirō was contracted with Tōhō, a major film and stage production company and a rival to Shōchiku, the company that manages and promotes many of the performances in the kabuki world. As a Tōhō star he played roles in contemporary theater, Shakespeare plays, and musicals.

“I didn’t choose to do musicals; Tōhō wanted me to. But if I were going to do musicals, I thought, I would do the best I could and make it all the way to Broadway,” says Kōshirō. “I could have decided not to do La Mancha or Shakespeare plays because I was a kabuki actor, but I decided to face the challenge.

“What is important in life is not what you experience, but whether you make decisions that you will not regret. There are times of hardship and sorrow in life, and I too have gone through such times. But there is no use in complaining about it. You’ve got to turn your grief into encouragement and hope in life. That is what I have always tried to do.”

Pursuing Kabuki as Drama

The history of kabuki shows a significant shift in the mode of performance presented on stage. Ichikawa Danjūrō IX modernized kabuki in the Meiji era (1868–1912) by adding elements of realism to the traditional theater. Matsumoto Kōshirō VII, Nakamura Kichiemon I (1886–1954), and Onoe Kikugorō (1885–1949) furthered this move by incorporating psychological elements in their performances. Now Kōshirō follows in their footsteps by pursuing kabuki as a form of drama that appeals to contemporary audiences.

“In drama-led plays like Shunkan and Terakoya,(*1) I try to focus on the inner emotions of the characters. But the methods for expressing them must be native to kabuki.” Kōshirō goes on to stress this important difference.

“If you compare Man of La Mancha on Broadway to an oil painting, kabuki would be a traditional Japanese ink painting. The technique and materials are totally different. It is as different as a baseball game in Yankee Stadium and a sumō tournament at the Kokugikan sumō arena. I am not influenced by contemporary plays when I do kabuki and I never use kabuki techniques when I’m in contemporary plays.”

Sharing Kabuki with the World

Many foreigners have visited the new Kabukiza since its grand reopening. How can kabuki best showcase its appeal to the world?

“Kabuki has been acknowledged as an intangible cultural heritage by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, along with other traditional performing arts of nō and kyōgen and the bunraku puppet theater,” notes Kōshirō. “It can be difficult to promote them overseas because of the language barrier and cultural differences, but something that is really good can be accepted as something new, even if it is old. In that sense, I believe kabuki can offer fresh appeal to foreign viewers just as it is. So the best thing is to have people from around the world see kabuki at its home, the Kabukiza.

“My belief is that kabuki will have international appeal if it consists of plays presenting human drama that all people can relate to. It can’t be just a traditional performing art that is strange and exotic.”

(Based on a June 26, 2013, interview in Japanese. Interviewer Nakamura Masako is a reporter of Jiji Press. Photographs courtesy Matsumoto Kōshirō’s office.)

(*1) ^ Shunkan depicts the wavering inner emotions of the title character, a Buddist priest exiled to a solitary island for his attempt to subjugate the despotic Heike clan. Terakoya tells the tale of Matsuōmaru, who sacrifices the life of his own son to save the son of Sugawara no Michizane, a scholar of the Heian period (794–1185).