Documentary Film Festival Brings the World to Yamagata

Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

(*1), or YIDFF, Asia’s first international documentary film festival, has been held biennially since 1989. In contributing to the promotion of documentary films, the festival has won cultural prizes within Japan and has built itself a global reputation. The number of entrants in the competitions has swelled from 260 in 1989 to more than 1,000 in the most recent festival in 2013. Nippon.com asked Yamanouchi Etsuko, who has participated as an interpreter since the YIDFF was launched, what it is that draws so many people to a festival in one of the country’s smaller regional cities.

A Sense of Unity

Yamanouchi’s first time working at the YIDFF came about as a result of a coincidence. A language-services agent she was registered with was asked to supply interpreters to the festival. She recalls: “In 1989, I’d never interpreted at a film festival and I’d never thought very much about films or documentaries. So for me, getting work at the first YIDFF was really like pearls before a swine. I didn’t understand all the films that were shown, but I could sense the tremendous determination of the directors.”

At that time, documentaries did not have full acceptance as a genre in Asia. Directors fought a lonely battle to get their films made. “There have always been budget problems and endless other difficulties when making a documentary. But the directors don’t give up, because there are issues they want to address,” notes Yamanouchi. “These are people who call a spade a spade, and who really work to probe deep into the heart of things. And the YIDFF is a place for them to come together—somewhere for people to listen to minority voices, rather than just going along with dominant cultural forces, and think about what individuals living in a society can do to solve its problems. What captivated me about this festival was the similarity between its worldview and what I have been striving for.”

At that time, documentaries did not have full acceptance as a genre in Asia. Directors fought a lonely battle to get their films made. “There have always been budget problems and endless other difficulties when making a documentary. But the directors don’t give up, because there are issues they want to address,” notes Yamanouchi. “These are people who call a spade a spade, and who really work to probe deep into the heart of things. And the YIDFF is a place for them to come together—somewhere for people to listen to minority voices, rather than just going along with dominant cultural forces, and think about what individuals living in a society can do to solve its problems. What captivated me about this festival was the similarity between its worldview and what I have been striving for.”

Yamanouchi was not the only one. Many at the YIDFF felt the same sense of unity. “Filmmakers who’d put everything they had into their documentaries met others in the same situation. This helped to reinforce their conviction that they were doing the right thing—that they should keep at it. The YIDFF is that kind of event.”

Yamanouchi interpreting at the YIDFF International Competition. (Photograph courtesy YIDFF.)

Yamanouchi interpreting at the YIDFF International Competition. (Photograph courtesy YIDFF.)

Drawing the Line on Filmmaking Ethics

Documentaries can be defined in different ways. Some revolve around interviews, while others are shot in the same way as fictional films. There are also an increasing number of “self-documentaries” based on casual shooting by directors of events around them.

On November 18, 2013, Yamanouchi and Hara Kazuo, director of The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On, discussed documentary films and the YIDFF at a follow-up event at Uplink in Shibuya, Tokyo.

On November 18, 2013, Yamanouchi and Hara Kazuo, director of The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On, discussed documentary films and the YIDFF at a follow-up event at Uplink in Shibuya, Tokyo.

Yamanouchi describes the variety of the genre: “There’s no such thing as perfectly objective reporting, so even documentaries that appear objective are always affected by the director’s point of view. Ten different directors will treat the same social phenomenon in ten different ways, producing ten different films. To put it the other way around, though, I believe it’s the very strength of that individual vision that makes it possible for a film to speak to a large number of people.”

However, translating that vision to the screen is not a perfectly transparent process. “The camera has a large presence in documentaries. The people being filmed—and, of course, the people filming—are always aware that it’s there. Sometimes there can be a conflict about what is or isn’t OK to shoot.”

Although Yamanouchi is fascinated by documentaries, she admits to having some misgivings. One example is Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing, winner of the Prize of Excellence (the Mayor’s Prize) at the 2013 YIDFF. Shot from the perspective of the leaders of a death squad in Indonesia, the film has been praised for shedding light on the deeper layers of the human psyche. Yamanouchi says, though, “If I’d been someone who’d suffered at the hands of these men, the film would have left me shaking with anger.” Nonetheless, on hearing Oppenheimer talk, she was able to understand where he was coming from.

Anwar Congo (background), a death squad leader who admits to having killed 1,000 people, reenacts the scene of an actual massacre. The Act of Killing opened in Japan in April 2014. © Final Cut for Real Aps, Piraya Film AS, and Novaya Zemlya Ltd., 2012.

Anwar Congo (background), a death squad leader who admits to having killed 1,000 people, reenacts the scene of an actual massacre. The Act of Killing opened in Japan in April 2014. © Final Cut for Real Aps, Piraya Film AS, and Novaya Zemlya Ltd., 2012.

“What Oppenheimer is asking is how much we differ from the killer, Anwar Congo. He gave a detailed explanation of how he wanted to show the darkness inside everybody. And he had a strong desire to show a page of history that had been taboo until now. I could tell from his words that he had wrestled with the ethical questions and had undergone some desperate soul-searching while making the film. The appeal of documentaries is this kind of sincerity from filmmakers.

“We use different methods, but the act of conveying people’s thoughts is the same for interpreters. It’s not simply a case of lining up English words in place of Japanese. You have to understand the meaning of what you’ve heard and then communicate it. There are similarities between making documentaries and doing what I do.”

Yamanouchi says that this is not a job that can be done without emotional engagement. “When I’m interpreting, I can’t nullify my feelings about a film that I was watching together with the audience just a few minutes earlier. The best part of my job at the YIDFF is that interpreters are also expected to participate as human beings.”

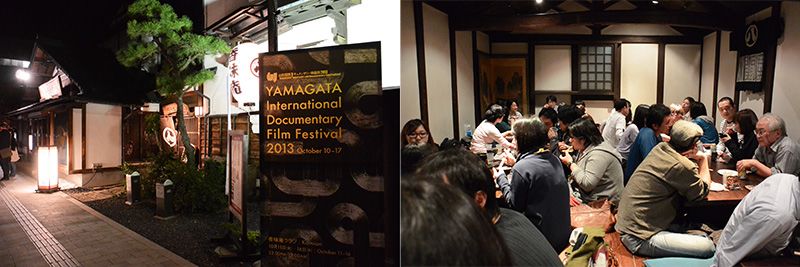

Traditional restaurant Kōmian is the gathering place for guests, filmmakers, and locals from 10:00 in the evening until the early morning hours each day during the festival. (Photographs courtesy YIDFF.)

Traditional restaurant Kōmian is the gathering place for guests, filmmakers, and locals from 10:00 in the evening until the early morning hours each day during the festival. (Photographs courtesy YIDFF.)

(*1) ^

Telling Their Own Stories

In the quarter-century since the launch of the YIDFF, the festival has helped to broaden the role of documentaries. A special program that was part of the 1993 event, the Indigenous Peoples’ Film & Video Festival, played a particularly large role in this regard. Yamanouchi explains: “For a long time, indigenous people had been controlled by others. In film, they had been seen only as material for the kind of works the powerful wanted to make. But these indigenous filmmakers wished to tell their own stories in their own words. In part because 1993 was the International Year of the World’s Indigenous People, the YIDFF decided to hold that special program highlighting them.”

At most film festivals it is the organizers who decide which works are shown. For the 1993 special program, though, the organizing committee granted this authority to the Aboriginal Film and Video Arts Alliance. This was in response to a request from the Alliance noting that images of indigenous people had been used freely by filmmakers who often did not bother seeking permission to do so. “If you determine the program once again,” argued Native American filmmaker Victor Masayesva, “our image will be exploited once again. But if you give us the right to choose the films, it will make the YIDFF a truly revolutionary festival.”

According to Yamanouchi, this paid off. “There was tremendous variety in the films chosen. A film by the Kayapo people in Brazil was shot by amateurs. They were using cameras for the first time to record poachers and to protect their forest. By contrast, there were also films shot in a sophisticated, dramatic style and works that had already been released around the world. We got this variety because the indigenous filmmakers had selected the films. They were demonstrating that from now on they intended to control their own image. I sensed we were standing on the verge of a new stage in film history. It gave me goose bumps as I was interpreting.”

However, the atmosphere that year changed completely when the YIDFF committee awarded the Grand Prize to Black Harvest, directed by Bob Connolly and Robin Anderson. The film tells the story of a mixed-race coffee plantation owner in the highlands of Papua New Guinea and his cooperation and conflict with tribal leaders who want to modernize. The indigenous filmmakers at the festival let fly with accusations that the film was told from a neocolonial perspective and that the subjects were not treated as human beings.

“Even now I agree with their sentiments,” says Yamanouchi. “There was a Maori director called Merata Mita among the judges. She must have felt like she’d been ripped in two. Having worked so hard to oppose that kind of film, how could she face people in New Zealand after that? It must have been hard. But the indigenous filmmakers chose to protest quietly, in a way that wouldn’t make the organizers lose face, by silently leaving the venue after the awards ceremony, before the film was shown. I felt this was the wisdom they’d learned from their long struggle with powerful forces.”

Experiences of Prejudice

As a visible and linguistic minority in Canada, Yamanouchi herself has experienced prejudicial treatment. When she was young, she spent a lot of time working on theater projects aimed at combating racial discrimination. She has also made the supporting of indigenous movements a major part of her life.

“When I think about it, I’ve been a linguistic minority even in Japan. The first time this happened was when I changed schools. Having been brought up in the mountains of Shikoku, in the fifth grade of elementary school I transferred to Matsuyama, the capital of Ehime Prefecture. It was only forty kilometers away, but the dialect was different so I had to adapt. Once I’d got used to how people spoke in Matsuyama, I started studying at a university in Tokyo where the intonation was totally different again. Then I moved to Canada and had to start functioning in English. Each time, I desperately tried to adapt in order to garner acceptance in the new community. I feel this experience has shaped my interest in minority rights. Canada has an image as an egalitarian country due to its multiethnic makeup, but there’s still discrimination. Indigenous peoples have been treated unjustly for centuries. And Japanese Canadians had a terrible time during World War II and for some time afterward.”

Yamanouchi notes that the YIDFF has helped to shed light on discrimination in Japan against the Ainu people and other groups. At the Indigenous Peoples’ Film & Video Festival, Chupchisekor, an Ainu participant, discussed the prejudice inherent in how Ainu people are depicted in popular Japanese films. Yamanouchi recounts how Chupchisekor said, “Despite the stereotypical, mistaken views, nobody criticizes them. That’s what’s shameful.” Yamanouchi felt that her eyes had been opened.

The Chance to Live True to Oneself

Yamanouchi expresses her wish for a world in which everyone can live true to themselves, and the individuality of minorities can be accepted by society. At the YIDFF, she has felt the possibility of that world coming into being. “Some people think they are powerless and that the world won’t change, no matter what they do. There are others who agree that there are many problems in the world, but they’re fully occupied just getting through each day. The people who come to the YIDFF, though—they somehow break out of this way of thinking and do what they can. They search for hints as to how to live better. And in fact, in the twenty years since 1993, the situation for indigenous people, for example, has improved a great deal.”

Yamanouchi's enduring hope is that her contribution to the YIDFF, no matter how small, may help bring about a better world.

(Photographs by Hanai Tomoko. With thanks to Uplink, Shibuya.)

References: Yamanouchi Etsuko, Akiramenai eiga: Yamagata kokusai dokyumentarī eigasai no hibi, Ōtsuki Shoten, 2013.

The YIDFF was launched in 1989 as part of the 100th anniversary celebrations of Yamagata becoming a city. Director Ogawa Shinsuke, who had spent years filming in the area, strongly influenced the decision to focus on documentaries. Since then, the weeklong festival has taken place every second October, featuring competitions for Asian and international films and special events in several venues across the city.

The YIDFF was launched in 1989 as part of the 100th anniversary celebrations of Yamagata becoming a city. Director Ogawa Shinsuke, who had spent years filming in the area, strongly influenced the decision to focus on documentaries. Since then, the weeklong festival has taken place every second October, featuring competitions for Asian and international films and special events in several venues across the city.

In 2006, the YIDFF Organizing Committee became independent from the city of Yamagata. Since 2007 it has managed the festivals as a nongovernmental organization.

Photograph courtesy YIDFF.

Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival: Major Award Winners and Attendance

| 1989 Total films shown: 80; Attendance: 11,920 | |

|---|---|

| International Competition | Award Recipients |

| The Robert and Frances Flaherty Prize (The Grand Prize) | The Crossroad Street (Ivars Seleckis, Soviet Union, 1988) |

| The Mayor’s Prize (Prize of Excellence) | Route One / USA (Robert Kramer ,France, 1989) |

| Runner-up Prizes | The Eye above the Well (Johan van der Keuken, Netherlands, 1988) Nobody Listened (Nestor Almendros, Jorge Ulla, USA, 1988) Weapons of the Spirit (Pierre Sauvage, USA / France, 1989) |

| Special Events A Salute to Robert and Frances Flaherty; The Dawn of Japanese Documentaries; etc. | |

| 1991 Total films shown: 153; Attendance: 14,486 | |

| International Competition | Award Recipients |

| The Robert and Frances Flaherty Prize (The Grand Prize) | Stubborn Dreams (Szobolits Bela, Hungary, 1989) |

| The Mayor’s Prize (Prize of Excellence) | Locked Up Time (Sybille Schönemann, Germany, 1990) |

| Runner-up Prizes | American Dream (Barbara Kopple, USA, 1990) Once There Were Seven Simeons (Herz Frank and Vladimir Eisner, Soviet Union, 1989) |

| Special Events Media Wars Then and Now: Pearl Harbor 50th Anniversary; The Post-war Flourishing of Japanese Documentary; etc. | |

| 1993 Total films shown: 139; Attendance: 20,509 | |

| International Competition | Award Recipients |

| The Robert and Frances Flaherty Prize (The Grand Prize) | Black Harvest (Bob Connolly and Robin Anderson, Australia, 1992) |

| The Mayor’s Prize (Prize of Excellence) | Zoo (Frederick Wiseman, USA, 1993) |

| Runner-up Prizes | Living on the River Agano (Sato Makoto, Japan, 1992) Losses to Be Expected (Ulrich Seidl, Austria, 1992) |

| Asia Program | Award Recipient |

| Ogawa Shinsuke Prize | 1966, My Time in the Red Guards (Wu Wenguang, China, 1993) |

| Special Events In Our Own Eyes / First Nations’ Moving Images; In Memory of Ogawa Shinsuke; Japanese Documentaries of the 1960s | |

| 1995 Total films shown: 278; Attendance: 21,028 | |

| International Competition | Award Recipients |

| The Robert and Frances Flaherty Prize (The Grand Prize) | Choice and Destiny (Tsipi Reibenbach, Israel, 1993) |

| The Mayor’s Prize (Prize of Excellence) | Metal and Melancholy (Heddy Honigmann, Netherlands, 1993) |

| Runner-up Prizes | Picture of Light (Peter Mettler, Switzerland / Canada, 1994) Screenplay: The Times (Barbara Junge and Winfried Junge, Germany, 1993) |

| New Asian Currents | Award Recipients |

| Ogawa Shinsuke Prize | Murmuring—A Woman Being in Asia 2 (Byun Young Joo, Korea, 1995) |

| Awards of Excellence | Scenes of Violence (Chen Yi-wen, Taiwan, 1994) Katatsumori (Kawase Naomi, Japan, 1994) |

| Special Events 7 Spectres: Transfigurations in Electronic Shadows; Japanese Documentaries of the 1970s | |

| 1997 Total films shown: 187; Attendance: 22,875 | |

| International Competition | Award Recipients |

| The Robert and Frances Flaherty Prize (The Grand Prize) | Fragments Jerusalem (Ron Havilio, Israel, 1997) |

| The Mayor’s Prize (Prize of Excellence) | Africas: How Are You Doing with the Pain? (Raymond Depardon, France , 1996) |

| Runner-up Prizes | Paper Heads (Dušan Hanák, Slovakia, 1996) Tu as crié LET ME GO (Anne-Claire Poirie, Canada, 1997) |

| New Asian Currents | Award Recipients |

| Ogawa Shinsuke Prize | Out of Phoenix Bridge (Li Hong, China, 1997) |

| Awards of Excellence | Paradise (Sergey Dvortsevoy, Kazakhstan / Russia, 1995) Work and Work (Fuad Afravi, Iran, 1996) |

| Special Events The Pursuit of Japanese Documentary: The 1980s and Beyond; Imperial Japan at the Movies; etc. | |

| 1999 Total films shown: 88; Attendance: 20,600 | |

| International Competition | Award Recipients |

| The Robert and Frances Flaherty Prize (The Grand Prize) | Images of the Absence (German Kral, Germany, 1998) |

| The Mayor’s Prize (Prize of Excellence) | Belfast, Maine (Frederick Wiseman, USA, 1999) |

| Runner-up Prizes | Sweep It Up, Swig It Down (Gerd Kroske, Germany, 1997) Happy Birthday, Mr. Mograbi (Avi Mograbi, Israel / France, 1999) |

| New Asian Currents | Award Recipients |

| Ogawa Shinsuke Prize | Swimming on the Highway (Wu Yao-tung, Taiwan, 1998) |

| Awards of Excellence | Beijing Cotton-Fluffer (Zhu Chuan-ming, China, 1999) Old Men (Lina Yang Tian-yi, China, 1999) |

| Special Events Ogawa Productions Program; Video Activism in Japan and Korea, Full Shot & Cinema Juku; etc. | |

| 2001 Total films shown: 173; Attendance: 18,490 | |

| International Competition | Award Recipients |

| The Robert and Frances Flaherty Prize (The Grand Prize) | The Land of the Wandering Souls (Rithy Panh, France , 2000) |

| The Mayor’s Prize (Prize of Excellence) | In Vanda’s Room (Pedro Costa, Portugal / Germany / Switzerland, 2000) |

| Runner-up Prizes | Mysterious Object at Noon (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Thailand, 2000) 6 Easy Pieces (Jon Jost, USA / Italy / Portugal, 2000) |

| New Asian Currents | Award Recipients |

| Ogawa Shinsuke Prizes | Soshin: In Your Dreams (Melissa Kyu-jung Lee, Australia, 1999) A True Story about Love (Melissa Kyu-jung Lee, Australia, 2001) |

| Awards of Excellence | More than One Is Unhappy (Wang Fen, China, 2000) Farewell (Hwang Yun, Korea, 2001) |

| Special Events Robert Kramer Retrospective; New Asian Currents Special; etc. | |

| 2003 Total films shown: 177; Attendance: 19,338 | |

| International Competition | Award Recipients |

| The Robert and Frances Flaherty Prize (The Grand Prize) | Tie Xi Qu: West of Tracks (Wang Bing, China, 2003) |

| The Mayor’s Prize (Prize of Excellence) | Stevie (Steve James, USA, 2002) |

| Runner-up Prizes | Gift of Life (Wu Yii-feng, Taiwan, 2003) S21, the Khmer Rouge Killing Machine (Rithy Panh, France, 2002) |

| New Asian Currents | Award Recipients |

| Ogawa Shinsuke Prize | Wellspring (Sha Qing, China, 2002) |

| Awards of Excellence | Hard Good Life (Hsu Hui-ju, Taiwan, 2003) The Old Man of Hara (Mahvash Sheikholeslami, Iran, 2001) |

| Special Events Okinawa—Nexus of Borders: Ryukyu Reflections; New Docs Japan, Learning, Teaching, Filmmaking, Yamagata Newsreel! ; etc. | |

| 2005 Total films shown: 145; Attendance: 19,963 | |

| International Competition | Award Recipients |

| The Robert and Frances Flaherty Prize (The Grand Prize) | Before the Flood (Li Yifan and Yan Yu, China, 2004) |

| The Mayor’s Prize (Prize of Excellence) | Route 181 (Michel Khleifi and Eyal Sivan, Belgium / France / UK / Germany, 2003) |

| Awards of Excellence | Foreland (Albert Elings and Eugenie Jansen, Netherlands, 2005) About a Farm (Mervi Junkkonen, Finland, 2005) |

| New Asian Currents | Award Recipients |

| Ogawa Shinsuke Prize | The Cheese & The Worms (Kato Haruyo, Japan, 2005) |

| Awards of Excellence | President Mir Qanbar (Mohammad Shirvani, Iran, 2005) Garden (Ruthie Shatz and Adi Barash, Israel, 2003) |

| Special Events BORDERS WITHIN—What It Means to Live in Japan, all about me? Japanese and Swiss Personal Documentaries; etc. | |

| 2007 Total films shown: 238; Attendance: 23,387 | |

| International Competition | Award Recipients |

| The Robert and Frances Flaherty Prize (The Grand Prize) | FENGMING A Chinese Memoir (Wang Bing, China, 2007) |

| The Mayor’s Prize (Prize of Excellence) | Encounters (Pierre-Marie Goulet, Portugal / France, 2006) |

| Runner-up Prizes | Potosi, the Journey (Ron Havilio, Israel / France, 2007) M (Nicolás Prividera, Argentina, 2007) |

| New Asian Currents | Award Recipients |

| Ogawa Shinsuke Prize | Bingai (Feng Yan, China, 2007) |

| Awards of Excellence | The Drown Sea (Yuslam Fikri Anshari [Yufik], Indonesia, 2006) Back Drop Kurdistan (Nomoto Masaru, Japan / Turkey / New Zealand, 2007) |

| Special Events Films about Yamagata; Facing the Past—German Documentaries; etc. | |

| 2009 Total films shown: 123; Attendance: 22,195 | |

| International Competition | Award Recipients |

| The Robert and Frances Flaherty Prize (The Grand Prize) | Encirclement—Neo-Liberalism Ensnares Democracy (Richard Brouillette, Canada, 2008) |

| The Mayor’s Prize (Prize of Excellence) | Oblivion (Heddy Honigmann, Netherlands / Germany, 2008) |

| Awards of Excellence | Z32 (Avi Mograbi, Israel / France, 2008) The Fortress (Fernand Melgar, Switzerland, 2008) |

| New Asian Currents | Award Recipients |

| Ogawa Shinsuke Prize | American Alley (Kim Dong-ryung, Korea, 2008) |

| Awards of Excellence | Bilal (Sourav Sarangi, India, 2008) This is Lebanon (Eliane Raheb, Lebanon, 2008) |

| Special Events Islands / I Lands—Cinemas in Exile; Against Cinema—Guy Debord Retrospective; etc. | |

| 2011 Total films shown: 241; Attendance: 23,373 | |

| International Competition | Award Recipients |

| The Robert and Frances Flaherty Prize (The Grand Prize) | The Collaborator and His Family (Ruthie Shatz and Adi Barash, USA / Israel /France, 2011) |

| The Mayor’s Prize (Prize of Excellence) | Nostalgia for the Light (Patricio Guzmán, France / Germany / Chile, 2010) |

| Awards of Excellence | Apuda (He Yuan, China, 2010) The Woman with the 5 Elephants (Vadim Jendreyko, Switzerland / Germany, 2009) |

| New Asian Currents | Award Recipients |

| Ogawa Shinsuke Prize | Yuguo and His Mother (Gu Tao, China, 2011) |

| Awards of Excellence | Amin (Shahin Parhami, Iran / Korea / Canada, 2010) Yongsan (Mun Jeong-hyun, Korea, 2010) |

| Special Events My Television; Great East Japan Earthquake Recovery Support Screening Project “Cinema with Us”; etc. | |

| 2013 Total films shown: 210; Attendance: 22,353 | |

| International Competition | Award Recipients |

| The Robert and Frances Flaherty Prize (The Grand Prize) | A World Not Ours (Mahdi Fleifel, Palestine / UAE / UK, 2012) |

| The Mayor’s Prize (Prize of Excellence) | The Act of Killing (Joshua Oppenheimer, Denmark / Indonesia / Norway/ UK, 2012) |

| Awards of Excellence | Revision (Philip Scheffner, Germany, 2012) The Other Day (Ignacio Agüero, Chile, 2012) |

| New Asian Currents | Award Recipients |

| Ogawa Shinsuke Prize | Mrs. Bua’s Carpet (Duong Mong Thu, Vietnam, 2011) |

| Awards of Excellence | Raging Land 3: Three Valleys (Chan Yin Kai and Choi Yuen Villagers, Hong Kong, 2011) Mohtarama(Malek Shafi’i and Diana Saqeb, Afghanistan, 2012) |

| Special Events The Ethics Machine: Six Gazes of the Camera; Memories of the Future: Chris Marker’s Trials and Travels; etc. | |

(Prepared by Nippon.com based mainly on information provided by the YIDFF website.)

film documentary Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival YIDFF Yamanouchi Etsuko interpreting