Cooking Guru Yukimasa Rika: Spreading the Gospel of Stress-Free Excellence

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

INTERVIEWER I understand you trace your interest in culinary arts back to your experience cooking for your American host family when you were studying overseas.

YUKIMASA RIKA Yes, I participated in an exchange program in Sonoma, California, when I was 18. I attended the local high school there for a year, but I wasn’t such a great student to begin with, and I didn’t have the money to attend university, so my original plan was to go back to Japan and teach English. But my host family recommended that I stay and attend the local junior college, and they offered to put me up for free if I would cook for them every Sunday through Thursday.

Until then, the only thing I’d ever prepared for them was potato soup. But after just one bowl, my American “father” decided I had talent, so he offered me the job.

INTERVIEWER So, it all began with a bowl of soup?

YUKIMASA That’s right. For about two years, I made dinner for them five days a week. And it was my good fortune never to be criticized. Praise makes people better cooks. I don’t think they always liked it, but they never criticized it. That’s why I kept going instead of deciding that I hated cooking.

INTERVIEWER Then you enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley?

YUKIMASA Yes, I was encouraged to apply for transfer admission, and I got accepted. At school, I cooked in the dormitory, and people would congregate whenever I was in the kitchen. I began throwing dinner parties on the weekend. People would chip in, and I would make them sushi rolls or whatever.

Building on One’s Strengths

INTERVIEWER But afterwards you decided to find work in Japan. Weren’t you tempted to stay in the United States?

YUKIMASA As a college student, I was really daunted by the competitiveness of American society. I thought, “I’ll never make it here,” so I went home. It was the second half of the 1980s, when Japanese corporations were going international, and people with English skills were in high demand. I was lucky enough to get hired by Dentsu. They put me to work as a copywriter, but I realized right away that I didn’t have any talent for it. I would be wracking my brains for hours, while people around me seemed to come up with better copy in a flash. So I quickly put in a request to be reassigned to commercial planning and production.

INTERVIEWER You didn’t waste any time, did you? A lot of people would have stayed put and knocked themselves out doing the job they’d been assigned, even if they knew they had no aptitude for it.

YUKIMASA My father used to tell me, “Find something that you can do better than anyone else within a five-kilometer radius.” The main reason I went abroad to study in high school was that English was the one subject I was decent at. As a copywriter, I could never have been the best within ten meters or even one meter. I thought my English skills would be better put to use producing commercials for overseas consumption or negotiating with foreign agencies—that sort of thing.

You often hear people say, “You can do anything you put your mind to,” but I don’t believe that. There are things you can’t do or hate doing, even if you work at them. For me, mathematics is one of those things. The moment I encountered radicals, my math career was over. It seems to me you have a better chance of fulfilling your career potential by doing what you love and building on your strengths than by knocking yourself out at something you’re no good at.

INTERVIEWER I understand you traveled overseas quite a lot when you were producing commercials.

YUKIMASA During the busiest months, I hardly spent any time in Japan. That experience has stood me in good stead. Wherever I went, I’d always check out the local supermarkets, because I love supermarkets. These days, I teach Japanese cooking to people from other countries on [the NHK World TV series] Dining with the Chef, and it’s really useful to know what kinds of ingredients and seasonings are available in local supermarkets overseas.

Going Solo

INTERVIEWER So, you left Dentsu in 2007, when you were forty-two years old. But at that point your career goals were focused on something other than cooking, am I right?

YUKIMASA I had my first daughter when I was thirty-six and my second when I was thirty-eight. And they were so much like me that I just knew that they, too, would despair when they got to radicals. I wished there were some way I could make their studies more enjoyable for them, and that’s when I lit on the idea of building a business around what they now call e-learning.

INTERVIEWER And you immediately quit your job to do it? That takes guts.

YUKIMASA Actually, my first thought was to write up a proposal for an in-house project. But when I floated the idea to a trusted higher-up, he said, “You’ll probably have to do it yourself.” And I thought he meant, “Go do it with your own money!” So I immediately started making preparations to leave. Afterwards, he told me that wasn’t what he’d meant at all! But in any case, I’d made up my mind. So, I used my severance pay and savings to establish my own company and set about gradually developing online content.

Years went by, but nothing clicked. Finally, this year, I won a Japan e-Learning Award for my online course “Karaoke English,” and the number of registered users jumped. After ten years, I feel the business has finally made it to the starting gate.

INTERVIEWER Meanwhile, though, you’ve been very active as a culinary expert over the past decade. What first inspired you to compile a cookbook?

YUKIMASA I had continued to cook after I returned to Japan from California, and during my years at Dentsu, friends and coworkers would ask me for recipes, and I would email them. The recipes kept getting forwarded, and the circle kept growing, until I found myself receiving thank-you emails from people I didn’t even know. I also got a lot of suggestions, like, “It could use a little more soy sauce,” and I would adjust the recipes accordingly. That’s why my recipes tend toward a happy medium that appeals to most palates.

Eventually, someone approached me about publishing the recipes in book form, and no sooner had the first book appeared than I was asked to compile another one, and so forth. Before I knew it, I had published about fifty books in twenty years.

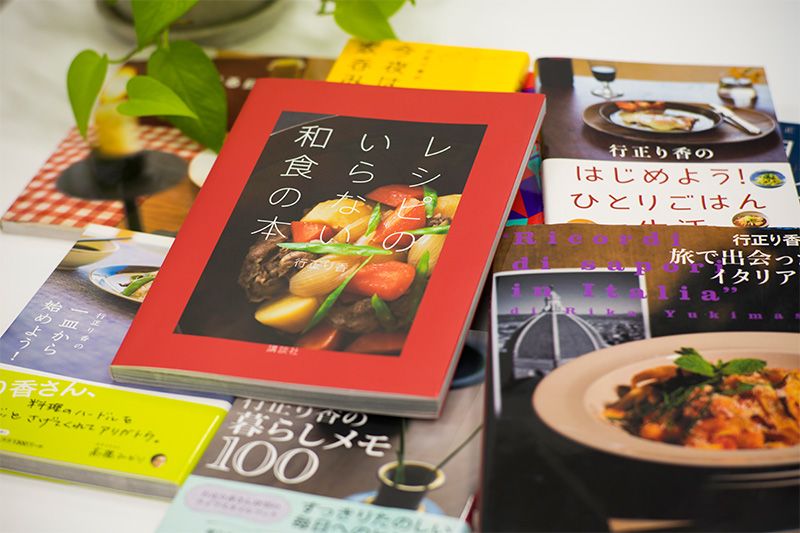

Yukimasa’s cookbooks are popular with Japanese working women.

Yukimasa’s cookbooks are popular with Japanese working women.

Tools for the Good Life

INTERVIEWER Is there a common thread between your cooking and English instruction?

YUKIMASA I want to convey what’s fun and rewarding about both. English is a global language, so if you’re proficient in English, you have opportunities to get to know all kinds of people, which is really rewarding. The same is true of cooking; it gives you opportunities to spend quality time with a lot of different people. And cooking is accessible to everyone. Both are tools for enjoying a rewarding life, and that’s what I’m trying to teach. That’s the thinking that inspires both my cookbooks and my English e-learning.

INTERVIEWER In the months ahead, Nippon.com will be carrying a series in which you introduce our readers to the techniques and flavors of Japanese cooking. What do you regard as the defining and appealing features of Japanese cuisine?

YUKIMASA You can search the world over, but you’ll have a hard time finding any other cuisine that uses so little oil. Of course, Japan has [Western-inspired] deep-fried dishes like tonkatsu and tempura, but most traditional cooking uses no oil or a tablespoon at most. Maybe that’s why the Japanese manage to keep their weight down even as they age.

Seasoning is pretty simple. The basic formula is equal parts soy sauce, sake, sugar, and mirin. Add water to adjust the level of seasoning, and you can make anything taste Japanese, from fish to vegetables. It’s quick and simple; there’s no need to simmer for hours because the time and care have already gone into making the seasonings, which are fermented. This is true of dried bonito and miso [as well as soy sauce, sake, and mirin]. The seasonings themselves are complex in flavor, so you can prepare delicious food without spending a lot of time on the cooking.

Japanese cuisine looks more complicated than it is, partly because of the dishes used to serve it. Of course, there’s beautiful plate-ware from all over the world, but I think Japan is exceptional in the variety of shapes and sizes we use. We have dishes for all purposes, from big platters down to tiny vessels a few centimeters in diameter. And they differ according to the season. I’ve never encountered that anywhere else in the world. Japanese tableware is really an art unto itself.

Getting Started

INTERVIEWER Can you share some tips on Japanese cooking for beginners?

YUKIMASA First, get rid of the notion that Japanese cooking is difficult. Forget anything you may have heard about buying a lot of exotic ingredients, or making dashi stock from scratch, or other hassles. Remember that you can season just about anything by using equal parts soy sauce, sake, sugar, and mirin. You can even use precooked rice, and instant dashi is just fine. In fact, most Japanese use instant dashi for everyday purposes. This idea that you have to begin by preparing dashi from bonito shavings and dried kelp is what closes the door to Japanese cooking for so many people and keeps them from getting to know it better.

I like people to begin by learning to cook a main dish with a lot of impact. You don’t want to spend too much time and effort at the outset fussing over details that hardly anyone will notice. That’s like spending your whole clothing budget on shoes.

If you want your table to look Japanese, get hold of some Japanese dishes about twenty-one centimeters in diameter, and place each on a white plate about twenty-six centimeters in diameter, along with a pair of chopsticks. That will instantly give your table a modern Japanese look. Don’t worry about each little detail. Just get started with one main dish. Japanese cooking is a delicious, healthy, and simple way to add zest to your life.

(Originally published in Japanese on November 1, 2017, based on an interview by Usami Rika. Photos by Natori Kazuhisa.)

Nippon.com is publishing a series of recipes by Yukimasa Rika in 2018: Shortcuts to Scrumptious Japanese Food.