Maruwaka Hirotoshi: Seeking a Future for Green Tea and Japanese Culture

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

To Complete In the Wider World

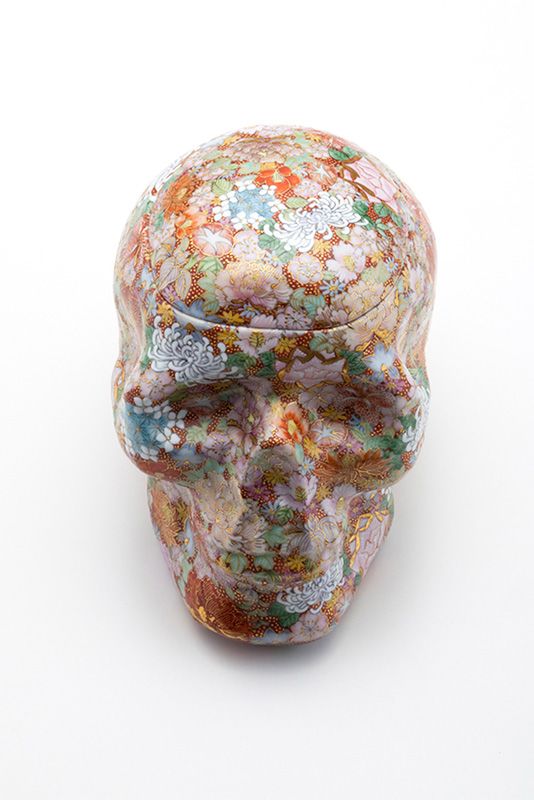

A flower-embossed, skull-shaped candy jar. (Courtesy of Maruwakaya)

A flower-embossed, skull-shaped candy jar. (Courtesy of Maruwakaya)

Japanese traditional crafts have long been objects of fascination and inspiration. Ranging from kimono made of beautiful glossy silk to ceramics, from lacquered bowls to tatami mats, from shōji paper screens to other household fixtures, these arts have been handed down across generations throughout Japan. Now, motivated by increased flows of tourism to Japan, as well as the impending Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games, increasing efforts are underway to express Japan in new forms through a fusion of the handwork of traditional artisans with modern designs.

Maruwaka Hirotoshi is a trailblazer in this regard, having established these trends in his role as a producer of Japanese handcrafts. In this capacity, he has traveled to centers of arts and crafts all over Japan, where he works with craftspersons to create many different items.

Examples include a candy jar in the shape of a human skull, which Maruwaka undertook in association with Kamide Keigo, the sixth-generation head of Kamide Chōemon-gama, makers of fine Kutaniyaki ceramics; ceramic vessels made through a collaboration between Kamide and world-renowned designer Jaime Hayon; round bentō boxes, known as mage-wappa, made of thin wood and sold by Puma; and iPhone covers derived from inden, traditional Japanese handbags, made of buckskin with lacquer patterns applied. All of these have a stark, stripped-down sensibility, even more so than the Japan-inspired designs that one sees so frequently of late.

Mage-wappa round wooden bentō boxes from Puma. (Courtesy of Maruwakaya)

Mage-wappa round wooden bentō boxes from Puma. (Courtesy of Maruwakaya)

Inden embossed leather iPhone covers. (Courtesy of Maruwakaya)

Inden embossed leather iPhone covers. (Courtesy of Maruwakaya)

Despite having acquired a reputation as a restorer of Japanese culture after more than a decade of these efforts, however, Maruwaka has concerns about the current boom in traditional Japanese crafts.

“It’s true that there are more products available now expressing the virtues of Japanese handcrafts,” says Maruwaka. “It seems to me, though, that many of these are just so much miscellaneous sundries. They may look Japanese enough to appeal to the foreign tourist market, but they’re hardly the real thing. As people become less discerning, and superior craftsmanship continues to go without the credit it deserves, the economic situations in the localities where these crafts originate gets more and more dire, as does the aging of the creators.”

Until his twenties, Maruwaka himself was like most other typical Japanese youth, in that he had practically no engagement with traditional Japanese crafts. His personal turning point came when he was 23 and pursuing a career as a street artist while supporting himself at a top foreign casual clothing brand. On a business trip to Ishikawa Prefecture, he was struck by the sight of a seventeenth-century ceramic platter of old Kutani manufacture which was on display at the Kutaniyaki Art Museum. “Here was something amazing, here in Japan, something far surpassing my ability of expression,” says Maruwaka. “We could be, should be, holding our own in the wider world with this.”

Collaborative efforts between Kamide Chōemon Kutaniyaki Ceramics and designer Jaime Hayon. (Courtesy of Maruwakaya)

Collaborative efforts between Kamide Chōemon Kutaniyaki Ceramics and designer Jaime Hayon. (Courtesy of Maruwakaya)

Maruwaka had no “in” with traditional Japanese crafts, however. On the strength of his enthusiasm alone, he personally made his way to the Kutaniyaki makers, as well as the makers of Ōdate mage-wappa round bentō boxes in Akita Prefecture and the lacquerers of Echizen-nuri in Fukui Prefecture. With characteristic sensitivity wherever he went, he proposed projects to make new kinds of products. As he worked steadily to forge bonds of trust, he also established his credentials a little at a time, such as by unveiling the inden iPhone covers and the Kamide Chōemon-Jaime Hayon ceramic vessels at DesignTide Tokyo, a leading design presentation event, to great acclaim.

Following his determination to compete in the wider world, in 2014 Maruwaka opened Nakaniwa, a gallery and store, in the Saint Germain quarter of Paris. He selected products for the store based on his own judgment, including kitchen knives made by Kama-asa—a cooking utensils shop in Kappabashi that is a common stop for top European chefs when they visit Tokyo—and Aritayaki Bunshō-gama porcelainware.

Reinvigorating Tired Traditional Industries

In Autumn 2016, Maruwaka unveiled his own original brand of Japanese tea at Nakaniwa. The following April, he opened Gen Gen An, a tea shop in Shibuya, Tokyo.

“I haven’t given up my involvement with handcrafts,” says Maruwaka. “To me, Japanese tea is a part of that. I got interested in it because it makes an easy-to-carry souvenir or gift, something that anybody can get ahold of. When I was trying to see what kinds of green tea would be popular in Europe, I realized that a lot of different kinds of knowledge is bound up with Japanese green tea, such as culture, history, and the thoughts and feelings of the tea makers. And I felt that it might be possible to extend ties between various peoples and Japanese culture further than before by bringing people together through this knowledge.”

An event followed which changed that instinct into a certainty. While on commission to conduct a workshop on Aritayaki ceramicware for the Musée des Arts asiatiques–Guimet in Paris, the ceramics artisan introduced Maruwaka to Matsuo Shun’ichi, a tea master from Ureshino in Saga Prefecture. Matsuo was an up-and-coming genius who, less than a decade after inheriting his family’s tea field business, had won the Japanese Minister of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries Prize, considered the most prestigious prize for green tea. According to Maruwaka, Matsuo was also looking to further extend the potential of Japanese tea.

“As we talked, I realized that the problems confronting traditional Japanese handcrafts were the same as those confronting Japanese tea, which is itself a traditional Japanese industry,” says Maruwaka. “Matsuo personally walks through tea fields throughout the country, drinking hundreds of kinds of green tea, conscientiously researching the relationships between environmental aspects like soil and sunlight and the flavor of the tea, and incorporating what he learns into his own tea-making. In more modern language, he is developing new products on the basis of market research. This sort of thing is a given in the corporate world, but it’s almost never seen in the realms of traditional Japanese industry, typified as it is by small-scale family businesses. On the one hand, I sensed that things couldn’t go on this way much longer. At the same time, though, I became certain that there must yet be tremendous latent potential in green tea.”

Traditional Japanese handcrafts and Japanese tea both face declining markets and the proliferation of inexpensive, low-quality products. There are fundamental structural problems, going beyond changes in preferences or diet, that have led to a situation where most Japanese can no longer tell which is the real thing: quality green tea made with traditional agricultural techniques, or tea made with additives to bring out the colors and sweetness of cheap tea leaves.

“If I’m going to do this, I want to compete on the basis of the taste of genuine green tea,” Maruwaka says. “Cultivating tea leaves as one would go about raising one’s own children, with an emphasis on natural agricultural techniques, should result in tea leaves that just naturally take on the terroir, the particular environment of the place where they are grown. Careful blending to control the aroma and astringency of each type of leaf can create green tea with a memorable taste, one that stands head-and-shoulders in individuality over what Japanese today have in mind when they think of green tea.”

Matsuo’s green tea even meets strict EU standards on use of agricultural chemicals, where many Japanese teas have failed in the past. “It really makes you wonder about the ways that much of the green tea that is sold in Japan gets made,” says Maruwaka with a grimace.

The Future of Japanese Culture

Having made original teas and even established a presence in Shibuya, the next key question for Maruwaka is how to raise awareness.

“I don’t just want to sell tea leaves,” says Maruwaka. “I want to offer a new lifestyle, one that allows time for the enjoyment of Japanese tea. For instance, I created a cold-brew tea you can make simply by putting a tea bag and cold water in a container and shaking it. This means that even young Japanese or foreigners who don’t know how to prepare green tea can easily have a drink without needing a traditional Japanese tea service. The first thing to do is to get people interested. You can introduce the various implements after you’ve done that. This is where the handcrafts which I’ve been involved with thus far will come together with green tea.”

In accordance with Maruwaka’s stated intent to broaden the appeal of Japanese tea, Gen Gen An feels like it belongs on the streets of Shibuya, with the counter which serves as the centerpiece of its interior, and the noticeable fashionable youth presence among the shop’s clientele. The menu ranges from such standards as kama-iri-cha (tea roasted in the pot rather than steamed) and hōji-cha (toasted tea) to such novelties as chamomile hōji-cha and lemongrass green tea. The shop does mainly takeout business, and its containers are primarily disposable cups, calling to mind a chain café.

“I want to redefine the very meaning of green tea,” says Maruwaka. “Some may critique me as looking down on tradition or tea ceremony etiquette, but Japanese culture also has a rebel aspect, one of constantly overturning rigid ways of thinking. For example, the shunga illustrations of the Edo period [1603–1867] were casually used as wrapping paper by ceramics exporters in the late 1800s—despite their artistic quality, which was evident to the Western people who were amazed by those packaging materials as creations in and of themselves.”

Maruwaka pouring cold-brewed green tea at the Gen Gen An counter.

Maruwaka pouring cold-brewed green tea at the Gen Gen An counter.

Maruwaka’s quest to compete in the wider world is already underway. In September 2017, at Maison & Objet Paris, a world-class interior design trade show, he worked with the Japanese creative organization TeamLab to present a digital art installation causing flowers and outer space alike to appear in cups of tea. The brand name for this project, En Tea, is rich with the sensibilities of Japanese culture, including the concepts of en, the joining together of various disparate objects and concepts, and ensōzu, drawings of circles in Zen Buddhist art.

“I don’t want to push culture on anyone,” Maruwaka says. “The sum total of my approach is simply to share green tea that needs no words to be loved—even by children on the other side of the world who know nothing about Japan.”

Maruwaka’s own inspiration and model is Baisaō, an Edo-period Zen monk.

“I got the name Gen Gen An from his last residence,” Maruwaka says. “He was known for passing himself off as a Chinese tea master and having philosophical conversations while making zencha, green leaf tea, at the side of the road—a reaction to the tea ceremony having become bound up with prestige and authority. I was fascinated by the idea that a rebel like this, someone we might call a punk today, was around 300 years ago.

“It doesn’t pay to be a hardliner about ‘the way things must be done.’ I think it gets much more to the essentials of tea to say, well, that looks interesting, and to find out that it’s delicious once you try it. Naturally, I want to be a part of Japan’s future, but it’s all because I want to hold my own in the wider world with things I like, not because I have any desire to change the situation of green tea or traditional Japanese crafts. If what I’m doing leads to some kind of change in the world as a consequence, then I’ll be happy.”

(Originally published in Japanese on November 8, 2017. Interview and text by Fukasawa Keita. Photographs by Ōkōchi Tadashi.)