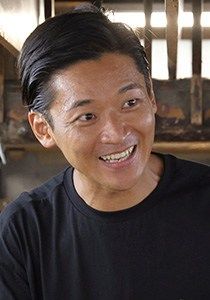

Hirose Dyeworks’ Hirose Yūichi: From Windsurfer to Fourth-Generation Craftsman

Culture People Fashion- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The dashing Hirose Yūichi is the fourth-generation head of Hirose Dyeworks, which has produced Edo-komon dyed fabrics for more than 100 years.

In the workroom in Tokyo’s Shinjuku, 7-meter-long boards fill the space. Stencils with delicate patterns are moved methodically down the boards to apply the pattern to the fabric. Moving the stencils so that the pattern is repeated seamlessly is the mark of an accomplished artisan. The work requires intense concentration in a space kept at optimum temperature and humidity.

Edo-komon originated with the dyed patterns used for the kamishimo formal overvests worn on top of kimono by samurai in the Edo period (1603–1868). Encouraging a lifestyle of simplicity and frugality, the shogunate would frequently issue edicts forbidding citizens from wearing showy clothing. But Edo residents, who loved flair and fashion, got around this prohibition by adopting a method of dyeing fabric that looked plain when viewed from afar but revealed a beautifully detailed pattern when seen up close. This was Edo-komon.

Patterns of stripes or minuscule dots resembling sharkskin were representative of Edo-komon, but many other symbolic patterns were also popular. For example, there was a dice motif, reflecting the popularity of dice games, for good luck; eggplants, whose smooth surface was equated to skin without cuts or abrasions; or chilies, to keep bugs, i.e., unsavory men, away. Optimum combinations of pattern and color were the mark of the truly stylish Edo-ite.

Today, just as in the past, Edo-komon stencils, made from three thin sheets of washi paper laminated with persimmon tannin, are produced mainly in the Ise region of Mie Prefecture. Stencil craftsmen use an etching knife, cutting into the material to create incredibly delicate patterns. The stencils, which combine high-quality paper, razor-sharp cutting tools, and typically Japanese attention to detail, are so sturdy that they can last 100 years or more.

A mixture of glue and dye is applied to the fabric through the stencil. The number of people present in the workshop can affect humidity, so the pace of the work needs to be adjusted accordingly. (© Hanai Tomoko)

Hirose’s fluid movements come naturally to him. That is as it should be, given that he is a former windsurfer selected as a potential team member for Japan’s participation in the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games. One wonders whether he felt conflicted about switching from being an athlete to carrying on the family business.

A Father’s Words: “Make This Your Last Competition”

“I spent a lot of time in the workshop as a child, so you could say it’s ‘dyed in the wool,’” laughs Hirose. “My father’s workers were a spirited lot, and in my eyes, they were so cool. I intended to eventually take over the craft, but as far as my life plans were concerned, I wanted to continue windsurfing until I was around thirty. But at the age of twenty-two, in my final year at university, my father took me aside the day before I left for an overseas tournament and suddenly said, ‘I suppose this will be your last competition . . .’ My grandfather was also fond of saying ‘You can start on this path at any age, but the younger you are, the better it will be all around.’ Ultimately, I just lost the will to compete; I came back home before the competition had even ended.”

Hirose was sad to leave his life as an athlete behind but was determined to make the switch and continue the family trade. Looking back, he says, “In a way, it was good that I wasn’t given any choice in the matter. It gave me the strength to persevere. And besides, I developed a genuine love for Edo-komon.“

Photos from the days when Hirose aimed to compete in windsurfing in the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games. Nowadays, he enjoys reminiscing over the photos with his children. (© Hanai Tomoko)

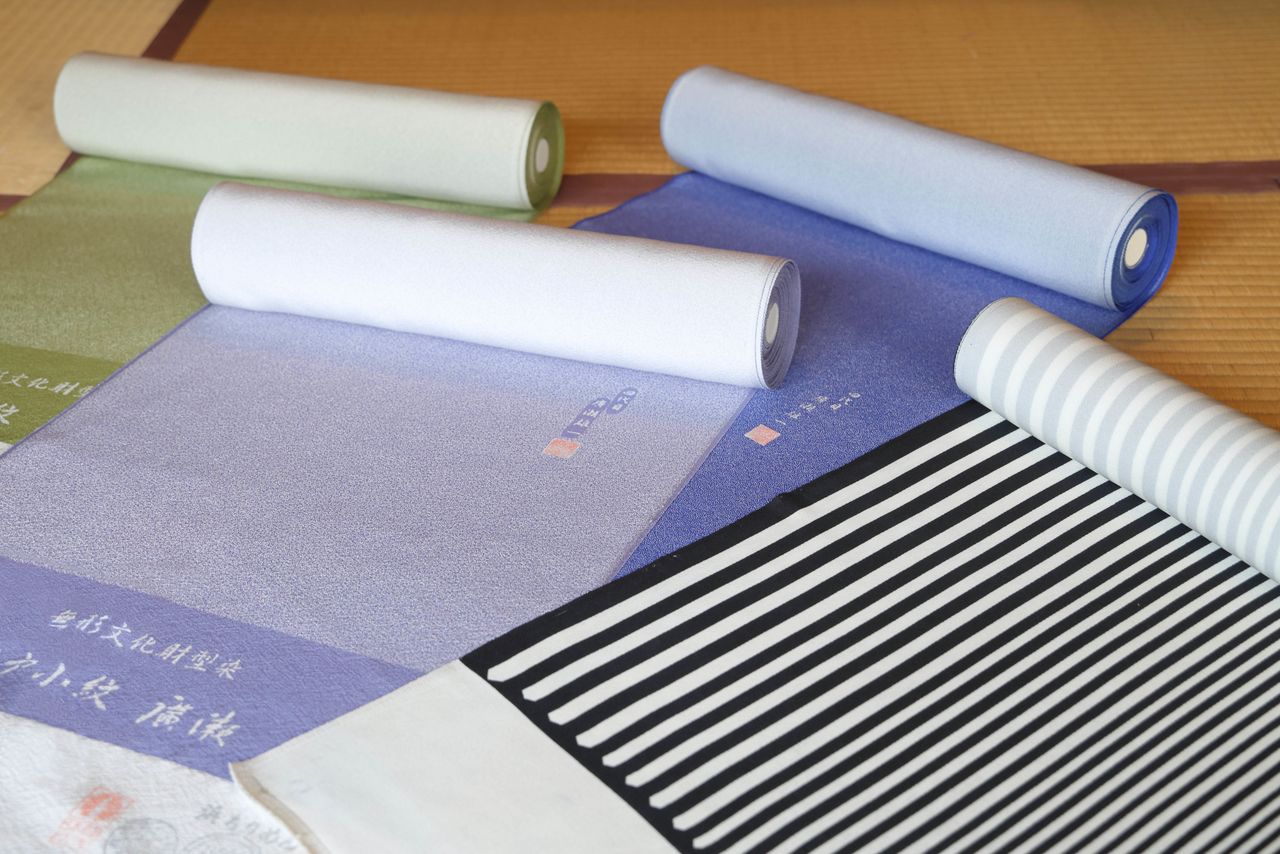

Now in his twenty-third year as a stencil-dyeing craftsman, Hirose continues: “Out of the myriad Edo-komon patterns in use, the most stylish is the stripe pattern. The stripes are plain and simple, just straight up and down, intersecting with no other lines. But with Edo-komon, the simpler the pattern, the harder it is to execute. There’s no room to fudge. One famous stencil maker etched thirty stripes onto a stencil just one sun, or a bit over three centimeters, square. I suppose he intended it as a challenge to any dyer. [Laughs] It’s a contest of wills between artisans. I can understand why dyers want to bring thin lines off beautifully, or their desire to take on dyeing a striped pattern as their last piece of work. That takes human skill to the limit.”

Kimono fabric is woven in bolts just over 30 centimeters wide. In addition to the stripe pattern on the right, Edo-komon comes in diverse patterns. The challenge for dyers is to decide which color to dye a particular pattern; depending on the dyer, subtle color differences can emerge. (© Hanai Tomoko)

Hirose acknowledges that stencil dyeing can be simultaneously difficult and enjoyable. As he speaks, his love and enthusiasm for Edo-komon are infectious.

Some successors in traditional crafts may never come to terms with the expectation that they will continue in the family line, but Hirose stresses that he was very fortunate that he came to love his métier so much.

Collaboration Gives Birth to “Paris Chidori”

But sales of kimono are flagging in the modern age, and it was not all smooth sailing when Hirose took over. To revive the business, he came up with the idea of creating Edo-komon stoles. That may sound like an outlandish project, but his predecessors had previous experience branching out into new territory. In fact, soon after World War II, Hirose’s grandfather began producing neckties combining traditional Edo-komon patterns with Western-style motifs. Coinciding with Japan’s postwar decades of rapid economic expansion, those sold very well, allowing the company to quickly get back on its feet after the difficulties of the wartime and immediate post-defeat years. It is clear that Hirose shares the forward-looking vision of his father and grandfather.

He also embraced broader horizons. Participation in an exhibition in Paris led to an invitation from the École des Arts Décoratifs de Paris, France’s most prestigious school for decorative arts, to conduct a workshop. There he was exposed to French students’ fresh, uninhibited sensibilities and ideas.

“Edo-komon was originally the epitome of freely expressed style. I don’t see the need to try retaining outdated patterns; what’s important is to preserve the skill of the craft, so it’s fine for patterns to evolve to suit the times.” Hirose purchased the winning design from a student competition, leading to the birth of “Paris Chidori,” a Paris and Edo-komon collaboration.

Featuring a popular seventeenth-century design modeled on the parquet flooring at the Palace of Versailles, this new Paris-komon created in 2023 is the result of Hirose’s collaboration with designers in Paris. The design was also written up in a French magazine. (Courtesy of Hirose Yūichi)

This collaboration made a splash and several major foreign couture houses approached Hirose. Working with them would have necessitated mass production, though, and while pondering whether to expand his business to take on this project, he came across the work of a dyer close to his own age.;

“I was completely bowled over by the beauty of his work. It renewed my appreciation for Edo-komon and made me question what I had been trying to do until then, looking for opportunities abroad and trying to do something ‘different.’ I decided then and there that working with my own hands was my future.”

This was the epiphany that renewed Hirose’s desire to perfect his skills as a dyer. “Nowadays, artificial intelligence can even reproduce the slight unevenness inherent in handwork. But I’m not interested; I don’t feel I need AI. Fundamentally, the beauty of an object lies with the human hand that made it. While there may not be major changes in the world of traditional art crafts, change is occurring incrementally. My thinking has evolved quite a bit from what it was ten years ago.”

That is where 45-year-old Hirose stands today.

“Riding the Waves,” a pattern crafted by Hirose for a long-sleeved furisode kimono for his daughter, who, like her father, aspires to world-class proficiency in wind surfing. The design features a traditional wave motif overlaid with a “running water” pattern. Hirose specifically chose the emerald green, blue, and white color scheme to complement his daughter’s deep tan. The kimono’s lining also incorporates a green wave pattern. (Courtesy of Hirose Yūichi)

“Overseas fashion houses may exude glitz and glamour, but deep down, their roots lie in history and craftsmanship, just like Edo-komon,” says the artisan.

Last year, Hirose was selected to participate in the Japan Traditional Art Crafts Exhibition for the fourth time. He also fulfilled his ambition of becoming a full-fledged member of the Japan Kōgei Association, a goal he had worked toward since being chosen to exhibit for the first time nine years ago. The strict examination he underwent to join this group focused on traditional arts and crafts forced him to take an objective look at his own work. He also learned that his work may change, depending on the direction he decides to take.

I ask how he envisions his future.

”I hope to work both as a craftsman bringing a client’s commission to life, and as an artist creating the kind of works I have in mind and later having customers wear them. Right now, I feel capable of doing both.”

Working in collaboration with a French designer, Hirose created a pattern this year that he named “Paris-komon,” applying it to fabric that has gone into stoles and a kimono displayed at events in Paris. Continuing to refine his top-class skills and creating unique works, this proud fourth-generation craftsman hopes to communicate the appeal of Edo-komon to the world and continue the tradition of his craft.

Hirose Dyeworks

- Address: Nakaochiai 4-32-5, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo

- Getting there: 10-minute walk from Nakai Station on the Seibu Shinjuku Line

- Tel.: 03-3951-2155

- Web: https://komonhirose.co.jp/hirose-senkoujou.html

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: To ensure optimum humidity, even today the workshop floor is hard-packed earth. Brushes and other tools used in the dyeing process hang neatly in the background. © Hanai Tomoko)