Korean Photographer Yang Seung-Woo Captures Society’s Underbelly

Art- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Photography Student with No Camera Experience

Yang Seung-Woo grew up in a quiet farming village in Korea’s southwest. As a child, he was nuts about world champion boxers, but there were no boxing gyms anywhere near his rural home for him to get a taste of the sport. “From about the second year of junior high, I went astray and was a bit of a rascal,” he recalls. Even after his military service ended, at 23, he says he continued to hang out with his delinquent buddies, idling his time away. He wanted to be “somewhere that wasn’t here” and got the idea to go to Japan.

After moving to Japan at age 30, he spent his first six months at Japanese language school. “It was the first time I’d studied intensely in my life,” he notes, but it enabled him to learn the language. Afterwards, he applied to a photography college in order to obtain a student visa, in what turned out to be a life-changing decision. Laughing, he explains: “It wasn’t that I was interested in photography—I chose the school for its location.”

From Shinjuku Lost Child. (© Yang Seung-Woo)

Up to that point, he had never even touched a camera, but Yang developed an interest in photographs while at college. Thereafter, he entered Tokyo Polytechnic University to study photojournalism in the Department of Photography, which he funded through a student loan and part-time work. One of his professors, the photojournalist Ōishi Yoshino, told students “Photograph whatever you like,” which Yang took to heart. Each weekend, he visited Kabukichō, Shinjuku’s infamous entertainment district, living rough in a cardboard hut to take photos. Weekdays he spent in the university darkroom, developing his photographs. Yang continued to capture life in Kabukichō for about eight years.

Kept Alive by Kabukichō

“When I first started photographing in Kabukichō,” says Yang, “I mistakenly believed that ‘good photos’ had to be of an incident or accident: something provocative, brash or shocking.” His decision to sleep rough was induced out of a fear of missing out: “I couldn’t help but feel that something would happen when I wasn’t there.” Yang was desperate to prevent anyone else from capturing such a critical moment.

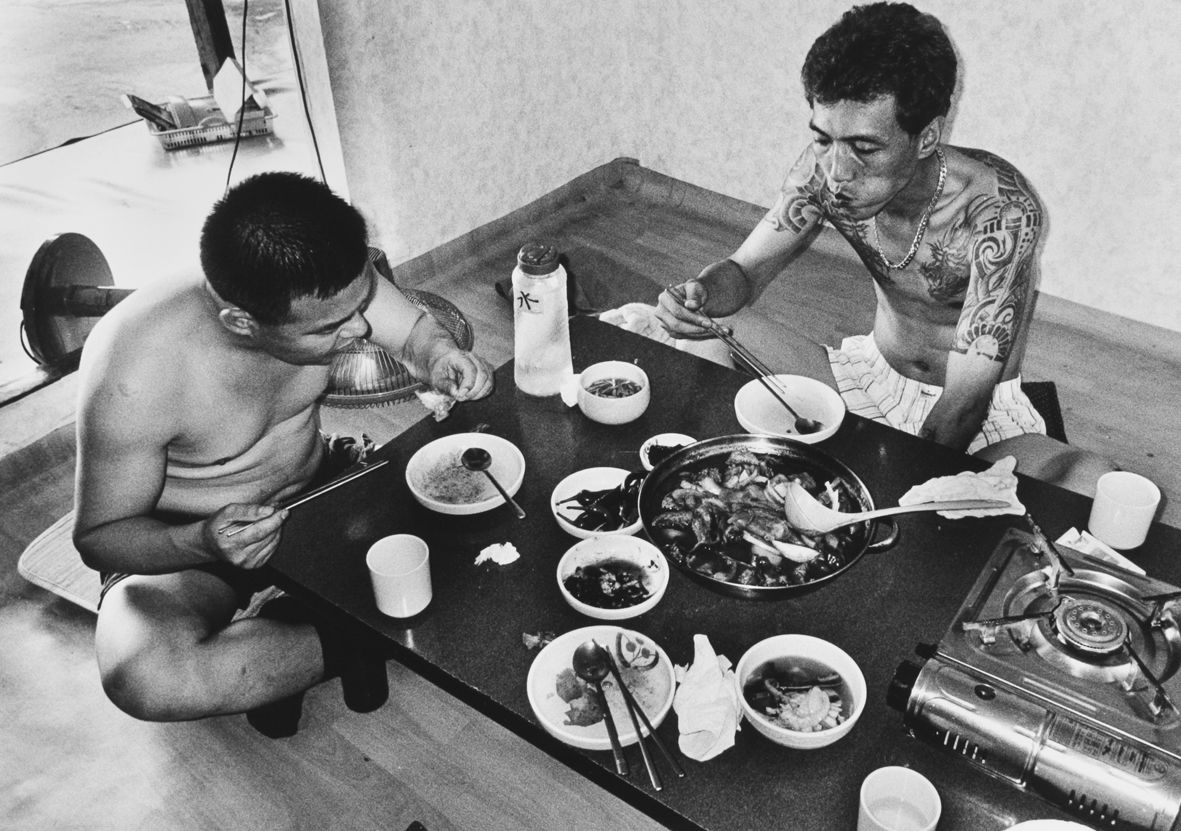

From Shinjuku Lost Child. (© Yang Seung-Woo)

He approached a member of the yakuza strutting about the town, directly asking “Can I take your photo? I’m a photography student,” fully aware he might knock him down. A few days later, he returned with a copy of the photo, and the man was so pleased that he allowed Yang to photograph his tattooed back, his hand with a finger cut-off, and the finger preserved in formalin.

During this period, he occasionally spotted children sleeping rough in Kabukichō, and over time, Yang’s view of his subjects began to change.

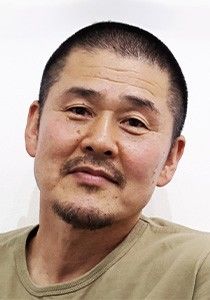

Yang at Zen Foto Gallery during his exhibition Baggage. (© Hanai Tomoko)

“I wondered why a child would be sleeping here at this time of night. It gave me a new perspective as I walked around Kabukichō, and I noticed there were actually many such children. It turned out that their mothers were working as hostesses and their kids were waiting outside. Then, I realized Kabukichō is more than just yakuza. I needed to convey other aspects if I was to express my love of the area in my photography.”

Eventually, these efforts resulted in his book Shinjuku Lost Child. But he went through years of hardship before being “discovered” by the book’s publisher, Zen Foto Gallery. He took his work from place to place, but was repeatedly turned down, with words to the effect that “It’s interesting, but impossible because it contains yakuza.” Yang recalls his dejection: “I thought about quitting photography.”

From Shinjuku Lost Child. (© Yang Seung-Woo)

But his pride stopped him from quitting outright. “I thought about deliberately having an accident to injure myself as an excuse.” He guzzled alcohol and haphazardly set out on a nonstop journey from Shinjuku to his apartment in Ikebukuro, taking photos along the way.

The next day, when he came to his senses, he ached here and there, but was uninjured. When he developed the film in his camera, all the traffic lights in the photos were red. Yang shuddered at the realization that he had not even stopped at the red lights. Having survived this risky venture, Yang felt that Kabukichō that kept him alive. It gave him fresh resolution: “If that was the case, I should keep trying a bit longer.”

Ongoing Work as a Street Vendor

From Yang-Tarō Baka-Tarō. (© Yang Seung-Woo)

Aside from Kabukichō, another formative influence on Yang as a photographer was the string of different part-time jobs he worked. After finishing his studies, he eked out an existence in strenuous jobs. He worked as a “carrier” on construction sites, scaling scaffolding carrying heavy materials, and laying carpets. Later, he worked in oil field exploration in Malaysia and Congo, and picked tea in Shizuoka until his hands turned green.

From Yang-Tarō Baka-Tarō. (© Yang Seung-Woo)

He compiled his photos from this period to produce the photo books Yang-Tarō Baka-Tarō (a derogatory term used in self-reference), and Tekiya (meaning “street vendors”). Yang thought working as a street vendor was “Killing two birds with one stone—I could take photos while working.” Through connections made in this line of work, he even managed to photograph the succession ceremony of a yakuza boss. He was astonished at the man’s confidence and dynamism.

From Tekiya. (© Yang Seung-Woo)

But the background to Yang being able to capture such rare photographs was probably his honest approach. “After I started street vending, it took me over a year before I took out my camera. There was no way I could ask to take photos before I could do the work satisfactorily. Ten years have passed since I started vending. I even worked as recently as this past New Year.”

From Tekiya. (© Yang Seung-Woo)

What’s in a Homeless Person’s Baggage?

“The belongings that homeless people carefully carry around with them contain their entire life.” This was the presumption behind his Baggage series of photos, which he started taking in 2008. Yang began approaching homeless people asking to take their portraits along with their possessions. He photographed over 60 people, mainly in central Tokyo, including Shinjuku’s Kabukichō and Toyama housing project areas.

The first person he photographed was the man in a trench coat who appears on the cover of his book. He was already acquainted with him, giving him the confidence to ask to see the contents of his bag. Despite his suspicion, the man spread out all his earthly possessions on a flattened cardboard carton. A half-used bottle of mayonnaise stood out among his things, spurring Yang to nickname the man “Mister Mayonnaise.”

“Mister Mayonnaise,” from the cover of Baggage. (© Yang Seung-Woo)

“I was expecting they’d have photos of their children, memorabilia, or other treasured possessions. In fact, though, their bags tended to hold much more than those ‘valuable’ items. Naturally, food is the most important thing for staying alive!”

From Baggage, a man in a cap who has amassed bread distributed to homeless people. “I won’t go into a shelter. They have curfews and I can’t enjoy my alcohol.” (© Yang Seung-Woo)

For Yang, who had also slept rough while taking photos, these people were valued neighbors. He sees two types of homeless people—those who are sociable and easygoing, and others who have cut themselves off from society. Not everyone is antisocial—Yang feels that the majority of homeless people are lonely and long for someone to talk to. He says that making small talk: “It’s hot, isn’t it?” “How’s your health?” “Do you want a drink?” is enough to convince most people to be photographed.

From Baggage. The suited man (right), previously homeless, accepted support and moved into a shelter a month ago. He still comes here each day to play shōgi with his friend. (© Yang Seung-Woo)

Yang says some people agree to be photographed but insist “Just don’t ask me anything.” He spends anything from 30 minutes to 3 hours on the street, drinking and talking with his subjects. “A lot of folk repeat their stories over and over, but I always try to react as if it’s the first time I heard it,” he laughs.

From Baggage. The subject’s dream is that “My kid graduates from university.” His motto: “Even the smallest worm has its share of will.” (© Yang Seung-Woo)

Yang has a set of questions he asks everyone: their age, birthplace, name, former profession, childhood and current dreams, and their message for society. He explains why he asks about childhood dreams. “Most people had dreams when they were a child, but they’ve probably forgotten them. I want to prompt them to recall those thoughts. The same with their current dreams.”

Gaining someone’s trust by sharing a drink with them is the secret to portrait photography, according to Yang. (© Hanai Tomoko)

Yang recalls a homeless person he knew for many years, originally from Kagoshima.

“All he did was drink—all day, every day. About six years ago I went looking for him—I was sure he’d still be around. Sadly, he’d passed away a year earlier. He had his last drink and lit his last cigarette, then just died, under the railway tracks. But he always said it was how he wanted to die, so I guess in a way he died happy.”

“I’ll Photograph You Again in Five Years”

Currently, Yang is taking portraits of youth in Korea. Around the time of the 2022 Halloween crowd crush, in Itaewon, Seoul, Yang was shocked to learn that South Korea had the highest rate of youth suicide in the world.

From The Best Days. (© Yang Seung-Woo)

“I’d just made arrangements to exhibit in Korea, so I thought I’d speak to young locals about it. A lot of young folk who come to my exhibitions are suffering emotional hurt. These days, the emphasis on educational background is even stronger in Korea than in Japan. Many young people who fail to gain a place at university are treated as subhuman and struggle with life. Some of them cried with the encouragement they felt seeing my photos of Japanese yakuza and Korean delinquents.”

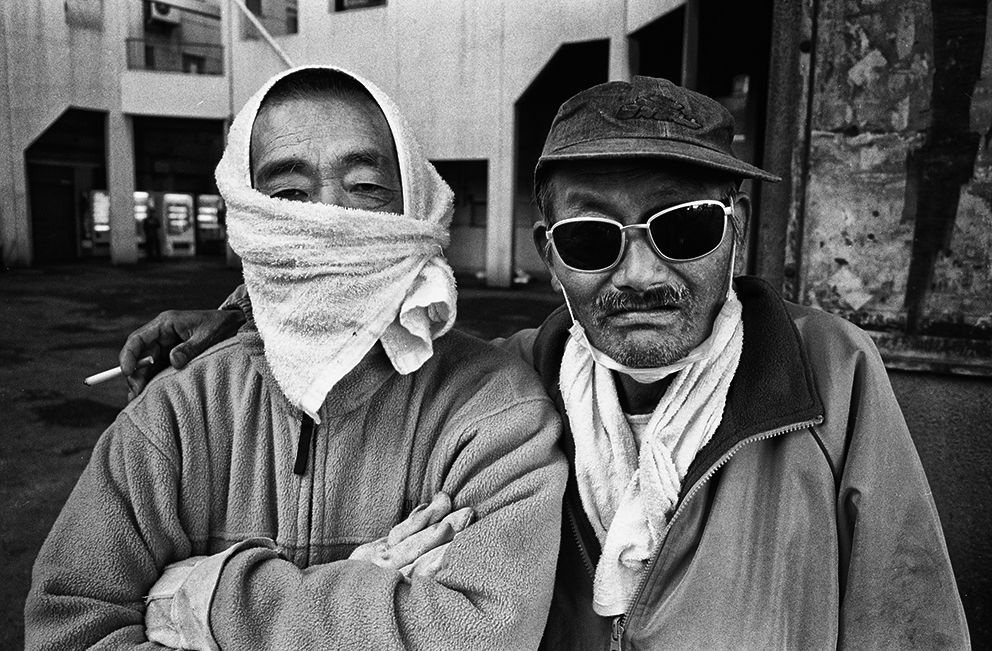

From End of the Line Kotobukichō. (© Yang Seung-Woo)

“What should I do when I see that? Well, there’s no need to say anything in particular. They’re so happy if I pat their back and say ‘Shall we step out for a cigarette?’ This prompted me to start a series of portraits of these youth at their favorite places. I ask them to tell me exactly what they’re thinking, even if it’s profanity, then I promise I’ll photograph them again in five years’ time. I hope they’ll resolve to live another five years so they can have me take their photo again.”

As our interview is ending, Yang takes out his smartphone to show us a photo of a Korean youth. He looks particularly pleased, saying “This series is the best.” But the subject’s expression seems to reflect Yang’s own past as someone who fell off the rails.

All of Yang’s subjects have a look of openness about them. “When there’s someone I want to talk to, it all begins with talking to them at their level. And always with a smile.”

(© Hanai Tomoko)

(Originally published in Japanese based on an interview by Watanabe Reiko. Banner photo © Hanai Tomoko.)