Japanese Approaches to an Eco-Life

(Re)Built to Last

Culture Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A House that Bears the Traces of its History

Enter 47-year-old Takeuchi Akihiko’s home in Gunma Prefecture and the first thing that grabs your attention is a naturally curved tree trunk used as a beam to support the roof. This large black timber overhead gives visitors an immediate sense of the house’s 120-year history.

Back in the middle of the Meiji era (1868–1912), when the residence was built, it housed a shop that sold rapeseed oil used for cooking and lamps. Later, after kerosene came to replace that oil, the house was used to cultivate silkworms. With the decline of the silk industry after World War II the family business underwent yet another change, shifting to the cultivation of the konjac plant used to make the gelatinous food konnyaku, a specialty of Gunma Prefecture. Over those many years, the succeeding generations of the Takeuchi family carefully maintained the house, carrying out partial renovations as needed to suit the changes in the family business. Reusing what already exists, rather than knocking everything down to rebuild, has kept the family members in touch with their past. It has also enabled a more environmentally friendly lifestyle.

In 2005, Akihiko decided that the house should undergo a major renovation—for the first time in around 30 years—in order for it to better meet the needs of the three generations living under its roof, including his elderly father. His wife Satomi had at first considered leaving the old house intact while building a new, modern house elsewhere on the property. But she later became convinced that remodeling the old house was the best option.

Akihiko points out some of his reasons for wanting to preserve the venerable family home: “Houses built back during Japan’s economic bubble in the 1980s and early 1990s were already looking rundown after just 20 years. None of the building materials used in recent years can match the smooth texture of the pillars of old houses, black with soot. And there is also no way that a newly constructed place could ever re-create the wonderful memories I have of growing up in this Meiji-era house. Above all, though, it is my sense of respect for the earlier generations who lived here that prevents me from tearing it down to build a grand new house.”

Satomi, meanwhile, explains what persuaded her to continue living in the historic house: “The architect working on the remodeling plans told us that the wood used to build the house has grown even stronger and harder now that more than a century has elapsed. He said that as long as we reinforce its earthquake resistance the house can be inhabited for many years to come.”

It took around three years of repeated consultations with the architect Yamaki Hidefusa, who heads the firm CA-LAB, for the couple to work out the remodeling to match their ideal of a home blending traditional and modern elements. The feature of the house that pleases the couple most is the impressive black timber crossbeam. Carpenters back in the Meiji era made use of the natural curves of such timber to construct houses, in sharp contrast to the perfectly straight blocks of processed wood used to build contemporary homes. The design for the Akihiko and Satomi’s remodeled house centered on the effectively reuse of that magnificent crossbeam.

Akihiko’s father, Yoshishige, is also very pleased with how the remodeling work turned out, especially because it has helped showcase two additions made by his own generation: the sliding wood doors (obido) and the three central pillars made of zelkova (keyaki) lumber. Other elements of the house that were adapted for reuse include its lattice doors (kōshido), complete with the scribbles and doodles Akihiko made as a boy, and its wood furnishings (tategu).

The living room, featuring a thick, naturally curved timber crossbeam, is where the Takeuchi family enjoys relaxing together around a specially designed horigotatsu—a low table placed over a sunken area in the floor for people to stretch their legs.

Reshaping a House for Generations to Come

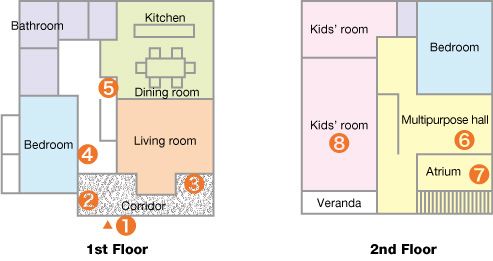

The remodeling of the Takeuchi home involved more than just preserving traditional elements and making the best use of resources. On the second floor, for instance, the partition walls in the kids’ room can easily be removed to suit their needs as they grow older. This is one way that the design takes into consideration the lifestyle of the family over the long term.

When she sees the light streaming in through the frosted glass in the lattice door, Satomi says, it vividly reminds her of what makes old homes so wonderful. “Even in an old house,” she explains, “it’s possible to live in a clean, comfortable way. We’re taking good care of what the house has to offer so it can be used for a long time. For earlier generations this sort of approach had been a matter of course. I hope that my own children will be able to continue living in this house.”

Taking good care of the precious things from the past, and using them far into the future, puts us in touch with those who came before us. It may also be the best way to preserve natural resources for future generations.

(Originally written in Japanese. Photographs by Ōtaki Kaku.)

Photo Album of the Takeuchi Home: A Traditional Approach to Green Living

Click on the numbers on the floor plan to get a closer look at how traditional elements are used in each room.

1 The glass tiled roof on the southern side of the house brightens the interior and makes it warm enough to dry clothes.

1 The glass tiled roof on the southern side of the house brightens the interior and makes it warm enough to dry clothes.

2 An extension was built to incorporate the veranda (engawa) outside the entranceway beams in the interior of the house. The design preserves the traditional Japanese veranda, where visitors can sit down for a chat without actually stepping further inside.

2 An extension was built to incorporate the veranda (engawa) outside the entranceway beams in the interior of the house. The design preserves the traditional Japanese veranda, where visitors can sit down for a chat without actually stepping further inside.

3 The entire ecologically friendly house can be heated with a stove fueled by pellets made by drying and compressing wood from thinned forests. This requires less space and effort than burning firewood and produces no smoke—eliminating the need for a chimney.

3 The entire ecologically friendly house can be heated with a stove fueled by pellets made by drying and compressing wood from thinned forests. This requires less space and effort than burning firewood and produces no smoke—eliminating the need for a chimney.

4 “The natural curves of timber are not uniform, so they defy machine analysis. Hardly any carpenters are being trained these days to assemble a house from natural timber, rather than processed wood,” explains Yamaki Hidefusa, the architect in charge of remodeling.

4 “The natural curves of timber are not uniform, so they defy machine analysis. Hardly any carpenters are being trained these days to assemble a house from natural timber, rather than processed wood,” explains Yamaki Hidefusa, the architect in charge of remodeling.

5 A pane of decorative glass from the early Shōwa era (1926–89) at the bottom of the stairs brightens the interior. This is one example of the use of antiques as design elements.

5 A pane of decorative glass from the early Shōwa era (1926–89) at the bottom of the stairs brightens the interior. This is one example of the use of antiques as design elements.

6 Using even fewer joists would have made the interior space feel more open, but many were left in place to strengthen earthquake resistance.

6 Using even fewer joists would have made the interior space feel more open, but many were left in place to strengthen earthquake resistance.