Japanese Approaches to an Eco-Life

Cooking Up a Do-It-Yourself Lifestyle

Culture Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Getting More Out of Less

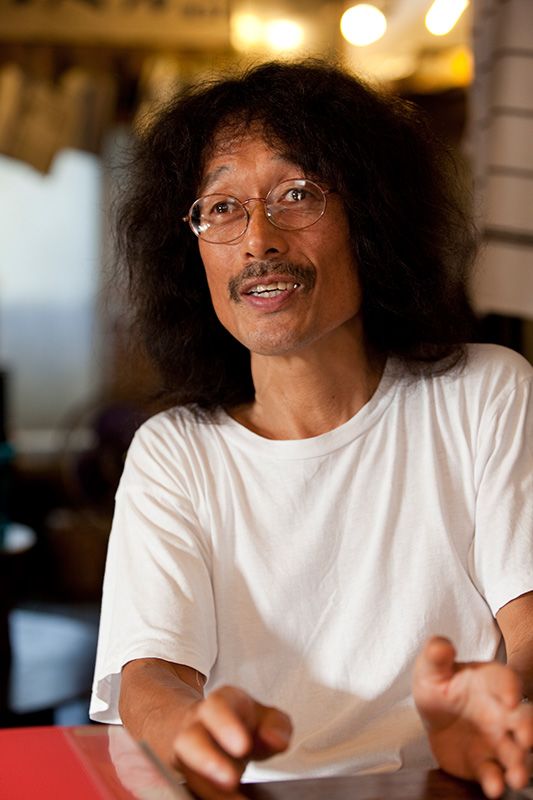

UOTSUKA Jinnosuke

UOTSUKA Jinnosuke

Born in 1956. After studying agriculture at university, spent 18 months running a motorcycle shop, followed by 10 years as the owner of a second-hand goods shop. Following up on this experience, he turned his attention to food culture and proposed unique ways to use food as part of a waste-free lifestyle. Numerous published works include Reizōko de shokuhin o kusarasu nihonjin (Japanese People Spoiling Food in the Refrigerator) and Tabemono no koe o kike! (Listen to What Your Food Is Saying!).

Over the past two decades or so, Uotsuka Jinnosuke must have seemed hopelessly behind the times to many of his fellow Japanese. While they were enthralled by consumption and convenience, his bywords remained conservation and creativity. His focus on getting more out of less—and his attitude toward food in particular—was out of tune with the “you are what you buy” mantra of consumer society, particularly during the go-go years of the bubble economy.

Why does he bother to stock up on dried vegetables, some must have wondered, when it is so easy to pop out to the store and buy whatever you need? Why not buy an air conditioner instead of sweating out the summer with an electric fan? Is he a glutton for punishment or what?

These days, though, more and more people see the wisdom behind the sort of simple and sensible way of living that Uotsuka espouses. The aftermath of the March 11 earthquake, in particular, was a wake-up call exposing how dependent Japanese people had become on their modern conveniences and how helpless they could be when store shelves were empty and the power was out.

Suddenly the idea of getting by with less and stocking up for a rainy day (or worse) seemed more like common sense than an eccentric habit. “Better late than never” may be the thought on Uotsuka’s mind as he sees people in Japan finally catching on to the sort of proactive and creative lifestyle he has been promoting in books and lectures for decades now as a researcher of food culture.

A visit to Uotsuka’s house in the Meguro district of Tokyo quickly reveals that he is a man who very much practices the simple life he preaches—right down to the plain white t-shirt he is wearing on the day we met him and his shaggy, shoulder-length hair that seems to require minimal daily maintenance. To step inside the house he shares with his wife is to enter a cozy, wood-paneled space that seems to have come straight out of prewar Japan. Instead of a flat-screen TV, air-conditioning, and other conveniences, one finds an open hearth in the center (used for heating in winter), a small wooden tea table, and antiques including a wall-mounted wind-up clock.

The whole atmosphere evokes a past time in Japan when people made up for the lack of material wealth by using their own ingenuity to spice up their lives. Far from suffering from the lack of modern conveniences, Uotsuka finds his way of life quite amenable. Indeed, he is quick to emphasize that he is not choosing a simple lifestyle out of some sort of stoicism. “I’m not doing as a sort of endurance test,” he explains with a laugh. “My view is that the best way to use things is to use them for a long time. This is my approach to food, too. So I buy lots of things when the prices are low and come up with ways to preserve the food for a long time, creating as little waste as possible. For me, living in this sort of way is a lot of fun.”

Using food in a waste-free way—and saving money in the process—is a point Uotsuka emphasizes in his many books. In particular, he stresses that people should avoid making unnecessary purchases. This does not mean, though, that Uotsuka wants to tell people exactly how they should live their lives, as he explains:

“My approach is to just let people know how I’m living my life. I’d like people to consider whether true affluence comes from buying one food item after another, when some of them end up going bad in the refrigerator; and for them to consider whether the convenience and low cost of fast food outweighs the health drawbacks. I’d be satisfied if my books end up encouraging readers to take a second look at their own dietary habits.”

“My approach is to just let people know how I’m living my life. I’d like people to consider whether true affluence comes from buying one food item after another, when some of them end up going bad in the refrigerator; and for them to consider whether the convenience and low cost of fast food outweighs the health drawbacks. I’d be satisfied if my books end up encouraging readers to take a second look at their own dietary habits.”

“Eating is Life”

Born into a family that ran a Japanese restaurant in Kyūshū, Uotsuka may have seem predestined to be fascinated by food, but it took a serious accident at the age of 14 to truly awaken this interest. The accident left him without sight in his left eye and could have killed him had his luck been worse. This traumatic experience led Uotsuka to begin seriously thinking about how best to live his life. He realized that the heart of the issue for him came down to food, because eating is life itself. He also became keenly aware, though, that each day we live brings us one step closer to death. This awareness compelled him to rethink his dietary habits to enable him to live well in a way that does not waste time.

His new outlook on life led him to study agriculture at university and to decide after graduation to open a thrift store. He first made a name for himself by writing books on how to prepare everyday meals in a waste-free way. Seventeen years ago his book Uotsuka-ryū daidokoro risutora jutsu (Restructuring Tips from an Uotsuka-style Kitchen) created a stir by offering readers tips on how to get by each month spending just ¥9,000 on food. The book had a major impact at the time, just after the end of the free-spending years of the bubble, surprising readers with the revelation that it was possible to live well for very little money.

His books are full of useful tips on how to save money and make life easier. For example, Uotsuka explains one idea in particular:

His books are full of useful tips on how to save money and make life easier. For example, Uotsuka explains one idea in particular:

“If you have leftover root vegetables, like carrots, pumpkin, or daikon, you can thinly slice them and dry them out in the sun. After a week or so they will be completely dehydrated and can be stored in jars to be eaten at any time over the next six months or so. If you soak the slices in water overnight, they can be used right away in dishes like miso soup. Having this sort of stock on hand means I don’t have to worry about running out of food, even if I hole up in my house for a month to focus on work. After the March 11 earthquake a lot of attention was focused on preserved food and emergency supplies, but if you get into the habit of stocking food then there’s no need to panic in an emergency.”

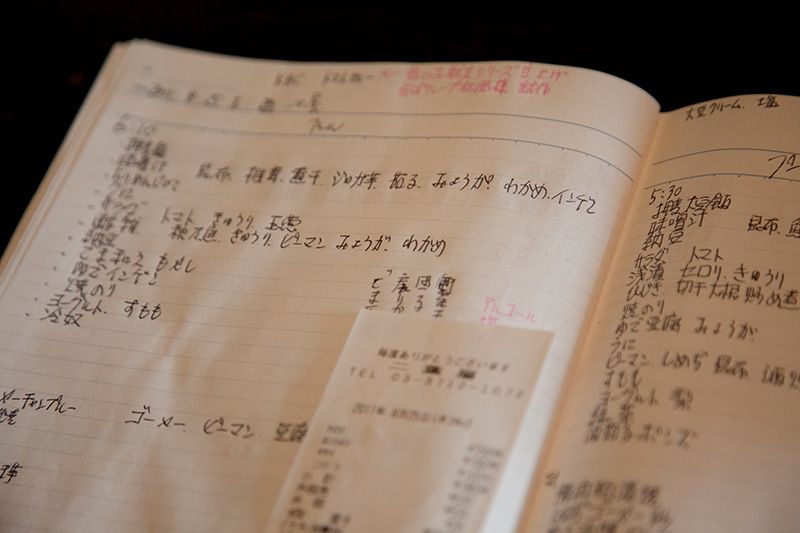

Another habit that Uotsuka has kept for over 20 years is to keep a “food diary” to jot down information about the food he buys and meals he prepares every day. “Looking back at past entries gives me a sense of how society has changed. I can also see how my own culinary tastes have evolved.” The diary is also a detailed record of how prices have changed over time, because Uotsuka includes receipts from his purchases.

Another habit that Uotsuka has kept for over 20 years is to keep a “food diary” to jot down information about the food he buys and meals he prepares every day. “Looking back at past entries gives me a sense of how society has changed. I can also see how my own culinary tastes have evolved.” The diary is also a detailed record of how prices have changed over time, because Uotsuka includes receipts from his purchases.

His economical way of preparing meals does not mean that he makes do with simple dishes, however. In fact, for breakfast he usually has over 10 different small dishes to eat, often including sashimi and even a bit of sake. What he does forego, though, is the custom of eating meals at restaurants, which is a rarity for him. Clearly, Uotsuka is a person who feels most comfortable in his house—every inch of which reflects his distinctive way of living.

His economical way of preparing meals does not mean that he makes do with simple dishes, however. In fact, for breakfast he usually has over 10 different small dishes to eat, often including sashimi and even a bit of sake. What he does forego, though, is the custom of eating meals at restaurants, which is a rarity for him. Clearly, Uotsuka is a person who feels most comfortable in his house—every inch of which reflects his distinctive way of living.

(Originally written in Japanese by Sakurai Shin. Photographs by Kawamoto Seiya.)

ingredients food ecology Uotsuka Jinnosuke waste lifestyle consumption consumer