Rice from the Mountainside

Culture Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

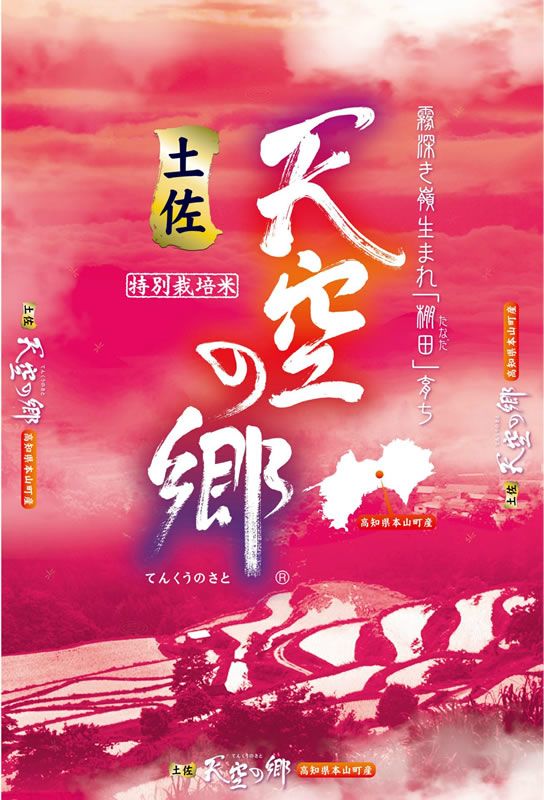

The town of Motoyama in central Shikoku, the smallest of Japan’s four main islands, is home to what has been dubbed the most delicious rice in Japan. Nestled between two mountain ranges in Kōchi Prefecture, the town is located near the headwaters of the Yoshino River and blessed with an abundant supply of water. On our trip there, we left the national highway and turned onto a narrow road through the woods. Five minutes later, a panorama of terraced fields suddenly came into view. Paddies filled with golden ears of rice ready to be harvested covered the valley and rose up to the top of the mountains.

The rice terraces of Motoyama rise from the bottom of the valley and spread across the hillsides, creating what feels like a “home of the heavens.”

The rice terraces of Motoyama rise from the bottom of the valley and spread across the hillsides, creating what feels like a “home of the heavens.”

An Unknown Name Takes First Place

Many were surprised when Tosa Tenkū no Sato Nikomaru—a name meaning “Nikomaru of Tosa [an old name for the southern part of Shikoku, where Kōchi is located], Home of the Heavens”—won first place in the 2010 Best Rice competition. Never before had rice produced in western Japan, let alone a variety other than the nationally popular Koshihikari type of grain, earned this distinction. Farmers and researchers were amazed that this newcomer, first marketed in 2009—and what is more, a variety developed not for flavor but for its ability to withstand warmer temperatures—had taken the prize.

Many were surprised when Tosa Tenkū no Sato Nikomaru—a name meaning “Nikomaru of Tosa [an old name for the southern part of Shikoku, where Kōchi is located], Home of the Heavens”—won first place in the 2010 Best Rice competition. Never before had rice produced in western Japan, let alone a variety other than the nationally popular Koshihikari type of grain, earned this distinction. Farmers and researchers were amazed that this newcomer, first marketed in 2009—and what is more, a variety developed not for flavor but for its ability to withstand warmer temperatures—had taken the prize.

Wada Kōichi, a vice-secretariat at the Motoyama Agriculture Corporation, which was behind the plan for creating a local brand, happily laments: “Ever since Tosa Tenkū no Sato Nikomaru won the competition we’ve gotten a lot of inquiries, and production can’t keep up with demand.”

A nearby stream flows downhill, permeating the terraces and later converging with the Yoshino River.

A nearby stream flows downhill, permeating the terraces and later converging with the Yoshino River.

Wada stresses that though Tosa Tenkū no Sato is new, the foundation for its success was laid a very long time ago. “Investigations show that grain was cultivated in Motoyama as far back as the Jōmon period [ca. 10,000 BC–300 BC]. During the Warring States period [1467–1568], one of the region’s rulers from the Motoyama clan sought to increase food supply for the people by expanding farmland, and the result was the rice terraces we have today. The clay soil of the region was perfect for producing high-quality rice. Though land at higher elevations is generally thought to be unsuitable for paddies because of the difficulty of securing enough water, our area fortunately has abundant spring water from the mountains. And in fact, the gap between the lows and highs in temperature is what gives the grains their plumpness.”

Protecting and Preserving Local Rice Terraces

In recent years, however, the town of Motoyama, like many other rural areas, has been hit by the winds of change. Farmers are growing older, and young people in the area are increasingly opting out of farming because mechanizing the operations on the terraced fields is difficult and the work remains so labor-intensive. In the beginning of the 2000s a group of farmers in their thirties and forties came together with the goal of saving the terraces. They decided to create a local brand that would make full use of the Motoyama’s abundant water and fertile mountain soil. Two varieties of rice were selected for cultivation. One was Hinohikari, which is popular in western Japan; the other was Nikomaru, which could resist warmer temperatures. Wada says, “We decided not to plant a variety developed for superior flavor and instead chose common varieties to show how Motoyama’s environment and cultivation methods can make the difference.”

Close attention was paid to how the rice was grown and marketed. Farmers participating in the project had to be certified as eco-farmers by Kōchi Prefecture, so that everyone was working from the same source of information on proper amounts of pesticides and fertilizers. Older farmers also took part, freely sharing their experiences and knowledge with younger people.

Strict standards were set for the size, color, and other characteristics of the grain. For most strains of rice, sieve with 1.8 millimeter mesh openings is used to separate grains that are too small from the rice that goes to market. The sieve used for Tosa Tenkū no Sato, however, has 1.9 mm openings. Only larger grains can be sold. Producers attended tasting events at department stores and other places so they could meet with consumers and use this input to improve the cultivation process.

Ōishi Naoya, a local farmer who worked with Wada to create Tosa Tenkū no Sato, talks about why he got involved.

“These terraced fields are our home and heritage, and I decided I would do whatever I could to preserve them. The first step was finding a way to ensure that people could make a living from rice farming. I contacted some younger farmers in town, and we decided to market our own brand. People said Shikoku rice wouldn’t sell, but we still wanted to give it a try. The first time its flavor was praised at a tasting event, we were ecstatic.”

New Pride in Farming

The third year the new brand was harvested, in the autumn of 2011, the number of farmers participating in the project had doubled from the initial 20 to 40.

“The award is a source of pride and confidence to us,” says Hosokawa Fuyuko, who uses an old but cherished sickle to reap the rice.

“The award is a source of pride and confidence to us,” says Hosokawa Fuyuko, who uses an old but cherished sickle to reap the rice.

Fuyuko’s husband Kazuho works at a local bus company. He mans the combine harvester on his days off, while Fuyuko hand-harvests the rice plants the tractor cannot reach. Their pet dog Kuro accompanies them in the fields. “We use the combine here on the terraced paddies, but we have to cut with a sickle in places with sharp curves. The sickle has a serrated blade, and you don’t have to be strong to use it.”

On another paddy, Sawada Tomoko is bundling the rice straw into sheaves. “We feed this to our beef cattle. I make the bundles and cover them while it’s still light outside. This way they’re protected from the evening dew and stay dry. Motoyama is also known for a type of red cattle called Tosa Akaushi. It’s not a fat-marbled meat; the red meat is what’s delicious. I’m hoping that people come to know our cattle, now that our rice has become the number one brand in Japan.”

In the morning, dewdrops cover the ears of rice in the terraces. Farmers start harvesting in the afternoon when the fog has cleared away.

In the morning, dewdrops cover the ears of rice in the terraces. Farmers start harvesting in the afternoon when the fog has cleared away.

Taoka Kiyoshi, one of the farmers who grew the award-winning Nikomaru last year, shares his knowledge of the grain: “In other areas, farmers let the rice dry after harvesting it, but here in Motoyama, we wait until the leaves have turned yellow before we harvest. The extra time our grains have to ripen is the secret to the distinctive taste of Tosa Tenkū no Sato. This year we were hit by a strong typhoon in September, and it took longer than usual for the crop to mature, so we’re a bit worried. Weather can have a big impact on harvest time as well as taste. Perhaps, though, this variation is what makes our brand what it is.”

Taoka Kiyoshi, one of the farmers who grew the award-winning Nikomaru last year, shares his knowledge of the grain: “In other areas, farmers let the rice dry after harvesting it, but here in Motoyama, we wait until the leaves have turned yellow before we harvest. The extra time our grains have to ripen is the secret to the distinctive taste of Tosa Tenkū no Sato. This year we were hit by a strong typhoon in September, and it took longer than usual for the crop to mature, so we’re a bit worried. Weather can have a big impact on harvest time as well as taste. Perhaps, though, this variation is what makes our brand what it is.”

The local environment and the people’s commitment are the ingredients to the success of Tosa Tenkū no Sato.

(Originally written in Japanese. Photographs by Ōhashi Hiroshi.)

Kōchi premium rice Motoyama Tosa Tenku no Sato Nikomaru Hinohikari terraced paddies depopulation shortage of successors Best Rice competition Akaushi red cattle