An Explorer of Japanese Style

Politics Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Tiffany Godoy

Fashion consultant and editor. Since coming to Japan in 1997, she has edited print publications including Composite and Studio Voice. Her fashion journalism has been featured in the pages of Style.com, the New York Times, and WWD, and she has hosted style programs on NHK World TV and Japan’s WOWOW network. As an author, she has published Style Deficit Disorder and Japanese Goth; in June 2010 she launched a new magazine, The Reality Show. Her blog is at http://tiffanygodoy.droptokyo.com/blogs/

Modeling for Vogue Japan in photos that appeared in the department store Isetan’s show windows. Godoy did her own styling, using Yamamoto Yōji creations. (Photo by Hiropon.)

Drawn by Something Different

INTERVIEWER Let’s start by asking how you came to the world of fashion and what brought you to Japan.

TIFFANY GODOY Well, I was born in California. As a kid—I must have been about eleven years old—I got really into fashion through movies and fashion advertising. I had a friend whose sister was a model for Calvin Klein. She introduced me to [fashion photographer] Bruce Weber’s work when I was twelve or thirteen, and beginning then I really got into visual imagery.

I found foreign magazines in the bookstore in a local shopping mall. I remember when Weber’s O Rio de Janeiro came out, I saw it at the store and thinking “Wow, what is this?” So this is how I got into images.

I spent a year in Paris, and my first encounter with Japan’s fashion came after I came back to the United States. I met these Japanese kids in San Francisco, where they were going to the Academy of Art University. We were all into the club scene, and I’d see them every week. I was fascinated by their look. I became friends with them, and that kicked off my interest in Japan.

INTERVIEWER What about their look interested you?

GODOY A number of things—the layering they did, the way they wore clothes of different patterns. These kids mixed together different colors and patterns that, for me, didn’t go together, but they just looked amazing.

Even their body language was different. This one girl had a certain way of holding her cigarette that I thought was the weirdest, coolest thing I’d ever seen. There were all these things about them that interested me. Theirs was a culture I’d never thought about before. I’d never had any direct contact with Japanese people, so they blew my mind—they opened a whole new world to me. I was fascinated and I wanted to learn more.

INTERVIEWER After this you made your way to Japan and got involved in the fashion scene.

GODOY I came to Japan, but I didn’t jump straight into fashion once I got here. Some Japanese friends from San Francisco introduced me to a number of people who ran a gallery near Tokyo’s Komaba district. It was a very artistic place, with artists and actors coming in and out.

I felt there was something I wanted to do in Tokyo. Once I was holding an exhibition at the gallery there. I invited a number of editors from Japan’s fashion magazines, and a lot of them came. Around a week later I got a call saying one of them, Sugatsuke Masanobu, wanted to meet me. I ended up as a fashion editor for Composite, a magazine he was publishing.

This brought it together for me. I’d studied photography, and this work let me put what I had learned to work along with my love for languages—for communicating with people. I’d never known what an editor did, but now I had this job where I could put all my skills to use at an edgy, cool fashion magazine. And that’s how it all started for me.

Godoy models a work by the Japanese artist King. (Taken at Garter in the Kōenji Kitakore Bldg., Tokyo.)

Click here for more on Kōenji’s Kitakore Building.

Exploring the Unique Aspects of Fashion

INTERVIEWER So you’d entered the fashion industry at last. But why the Japanese fashion industry?

GODOY Well, one of the reasons I’d wanted to come to Japan was because I really wanted to understand why: why the Japanese are so different from people in France or New York in terms of their aesthetic—the way they dress, their styling. It seemed so far from anything I had seen before. My image of Japanese people had been conservative and serious, so this creative side I saw made me want to understand more.

INTERVIEWER So while you worked at this fashion magazine house, you began gaining this understanding?

GODOY It took a while. I remember going to Comme des Garçons exhibitions and not understanding a lot of the clothes—but also understanding that I had to grasp why this brand was so important and influential. I was processing a lot of new information that was beyond my comprehension at the time, studying how to put together a magazine as well.

All my friends were Japanese and I was immersed in the culture. Japanese fashion was changing a great deal in the late 1990s. Women’s identities were changing too: this was when the young women called gyaru were a rising force on the cultural scene. I remember seeing Amuro Namie performing on the giant monitors at Studio Alta near Shinjuku station. Harajuku was also home to a lot of extreme fashion at that time.

Now this wasn’t high fashion, but a lot of things were happening culturally in Japan, with new subcultures being established. Youth culture was really strong and expressive then—very baroque, very decorated. It was exciting to me because it was all so distinctly Japanese.

Deep History Behind the Looks

INTERVIEWER What do you think is behind this? Why do Japanese people use layering or match different patterns and colors? What inspires the extreme gyaru styles?

GODOY There are a few things. I think Japanese people are very sensitive to aesthetics, and their looks are very designed. I trace this back to the Edo period [1603–1868], when Japan was closed to the outside world. This was when Japan’s aesthetics really evolved and gelled together.

First of all, Japan is an island country, so things are brought in from abroad and integrated into the culture. This is different from a country that’s connected to and always interacting with other countries.

Second is the idea of cycles, of connection to nature. This constant cyclical change is something that propels fashion’s evolution, and people’s links to nature show up in their sensitivity to colors and their meanings. The style of communication is also very different. In the past there was this tradition of kosode,(*1) where you might reference some scene from The Tale of Genji by incorporating a certain flower into the design of your robe, so that others who had read it would understand your message.

This is all linked to today’s street fashion as well. During those centuries of isolation in the Edo period, everything was simplified and refined; it became more structured. The ideas of Japanese minimalism and composition as we think of them today developed then. It was a very important period to how Japanese fashion would evolve later.

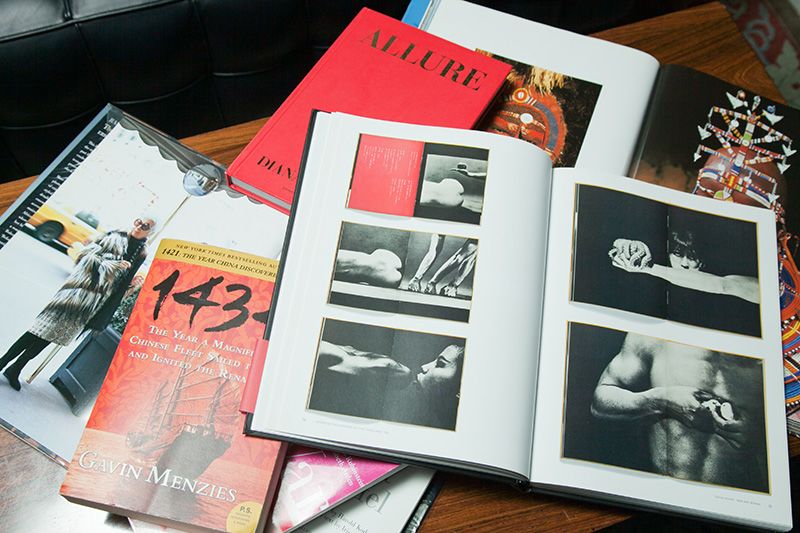

Godoy draws on a range of sources to produce guides to the complex field of fashion. Some examples on her current reading list: a collection of 1970s Japanese photos, a work on African tribal wear, leading fashion editor Diana Vreeland’s Allure, and a book on fifteenth-century Chinese seafarers.

After World War II the country entered another important period in fashion, one that saw a rejection of “Japaneseness,” or Japanese tradition, by the first generation of postwar designers—Yamamoto Yōji, Kawakubo Rei, and all the others who came here to Harajuku. There was also the idea of maintaining some elements of Japaneseness but also incorporating the youth culture that was evolving in the 1960s around the world. This was a time of energy in youth culture, music, and fashion, and this all got integrated through the sensibility of Japanese tradition, which these designers had grown up with. I think this was the course of development of a lot of what we see today in Japanese street fashion. This is what I’ve spent the last fourteen years trying to figure out! [Laughs]

Sharing Japanese Street Style with the World

INTERVIEWER You’ve published some books as well.

GODOY Yes. The first was Style Deficit Disorder: Harajuku Street Fashion in 2007. Basically I wanted to do a history of modern Japanese fashion. I didn’t think there was a true understanding of the fashion; people just thought it was crazy, or extreme, and didn’t know how it had developed. After working with respected Japanese fashion publications, I felt I had learned a lot and could share that understanding. Gwen Stefani had just come out with her “Harajuku Girls” song, so the topic was on the pop culture radar.

I decided to focus on the street fashion of this particular period. I wanted people to feel that they were in Tokyo, walking around on the streets, as they read through the book. It’s like a storybook, really, about how this one area was giving rise to so many new ideas that couldn’t have developed in any other place.

INTERVIEWER Your next book was Japanese Goth. Why focus on Goth instead of some other group?

GODOY Because it’s a very distinct Japanese subculture. Japanese Goth culture isn’t like German, or French, or American Goth culture. Why is it so different? Why do they cross-dress, with boys dressing like girls? It all leads back to old Japanese culture. Traditionally in Japan, men and women wear the same type of clothes. The kimono is unisex. So the idea of wearing women’s clothes isn’t strange at all.

There’s also a very specific moment in time when this style developed. It was just when the Japanese economy was getting really bad. All of a sudden you had no lifetime employment, no secure steps to take toward becoming an adult any more. Goth is sort of a girl version of otaku culture. It’s escapism. Living in a fantasy. It’s like being consumed by fear, in a way: fear of growing up.

But at the same time, I think these girls are amazing. It isn’t easy to wear clothes like that. They’re tough. These contradictions were fascinating to me.

An Eye on Young Style Leaders

INTERVIEWER In 2010 you launched a new fashion magazine, The Reality Show. Can you tell us about that?

GODOY The Reality Show is a new fashion publication that I launched with the art director Yonezu Tomoyuki. We publish twice a year and sell the print run in bookstores with strong fashion sections, in independent fashion boutiques, and via Colette, the Parisian fashion retailer. We chose an unbound print format that makes it easy to carry the magazine around with you but lets you spread its pages out to create poster-size visuals with its images. And we don’t focus on celebrity looks; we created this around the young people who are actually leading Japanese street fashion today.

I did the casting for this publication together with the websites Drop Tokyo and Tokyo Dandy. Sites like these are the media of young people today who are very serious about fashion, styling, and design.

I went to the people producing these websites because I wanted to be a part of this community—the most creative young people in Japan. You’ve also got a lot of international fashion industry people looking at these sites all the time, so they’re very relevant. We did a three-day casting session on the web, with viewers voting for the designers and models they wanted to see featured in the magazine. We went from there.

For the second issue, I went with a much broader range of people who represent many different aspects of Tokyo style. It’s important to go deeper than just featuring people who look cool. In Japan I think there aren’t many strong role models in this field, so I try to pick people I respect—people I think are talented—and talk to them, hopefully inspiring some other kids who are interested in fashion.

INTERVIEWER You’ve enjoyed success as a researcher of and writer on Japanese fashion. But this is different from creating your own images as an art director. Which would you rather do?

GODOY Oh, I think all these activities are very connected. Fashion isn’t just about an image: it’s about a story that tells why that image is necessary. I’m interested in working to help create experiences that are connected to the visual side. It’s communication—using the editorial voice to tell a story. And part of that story is told through visuals.

INTERVIEWER What you’re doing is quite far from the major magazine scene. It sounds like you’ve got a real creative focus on individual people, not brands.

GODOY Exactly. In fashion in general, you have this “top of the pyramid” occupied by brands with tradition, beauty—Chanel, Hermès—names with strong DNA. But I’m also interested in people who are at the top of the pyramid in the sense that they’re leading and doing new things. Now more than ever, people are aware of that. People are much more aware of fashion and fashion culture now than they were ten years ago. These Japanese website producers are celebrities in Asia—they’re very influential in Korea and China.

So I don’t want to use the term subculture here. This is mainstream culture.

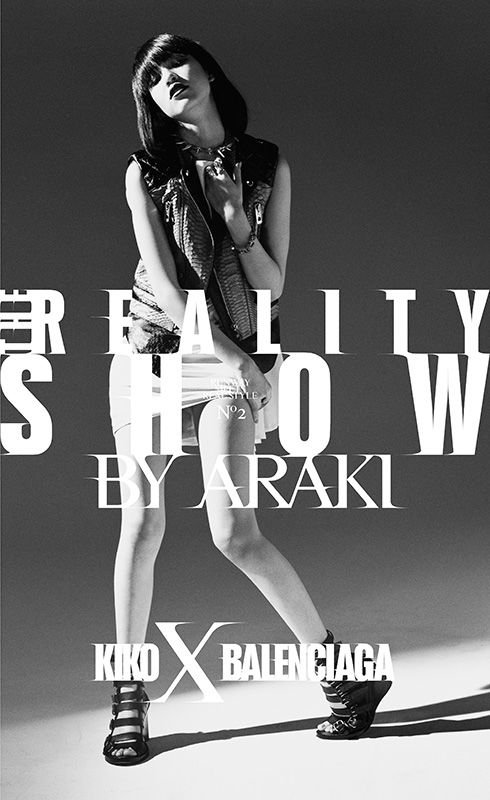

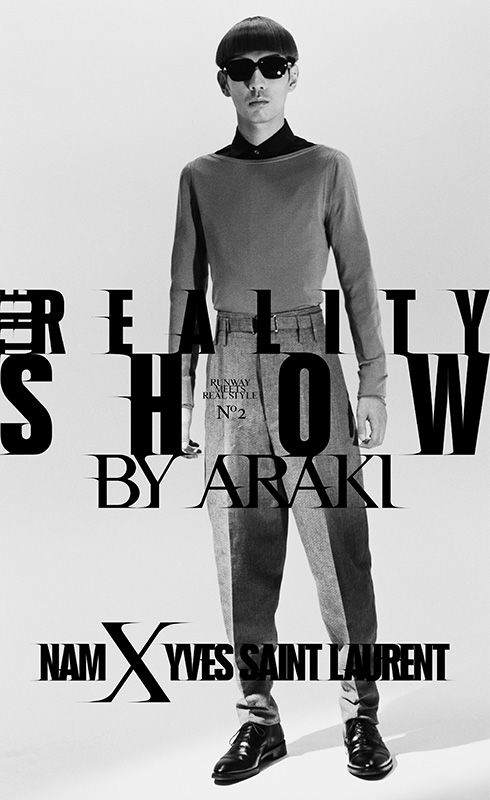

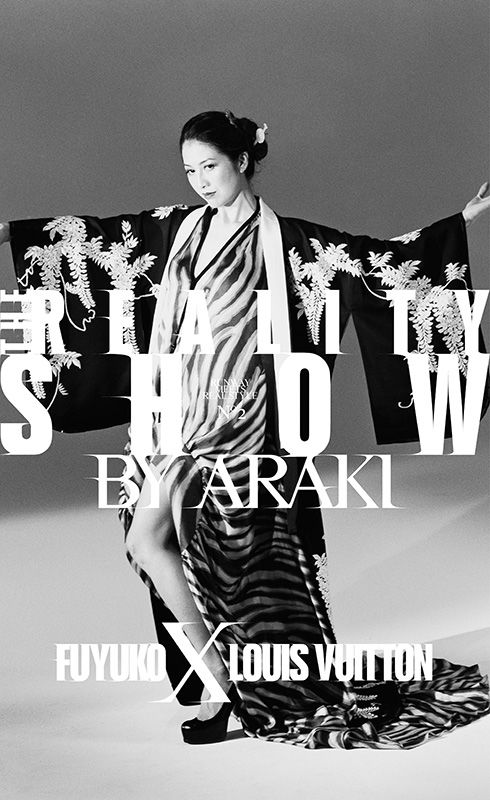

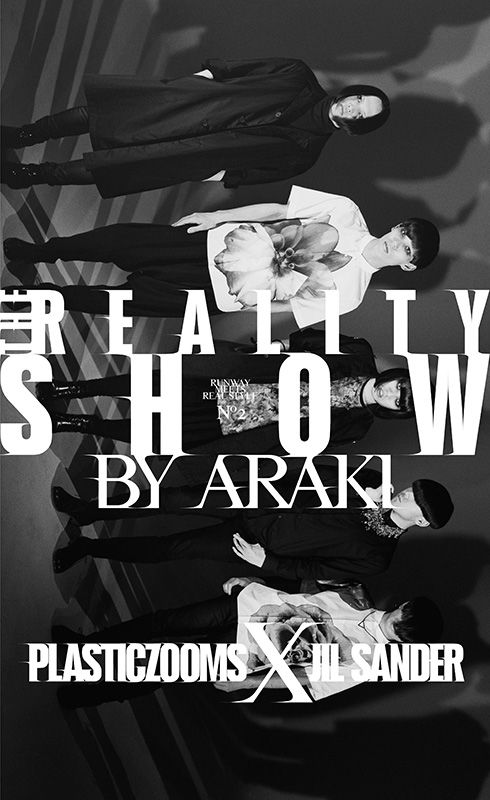

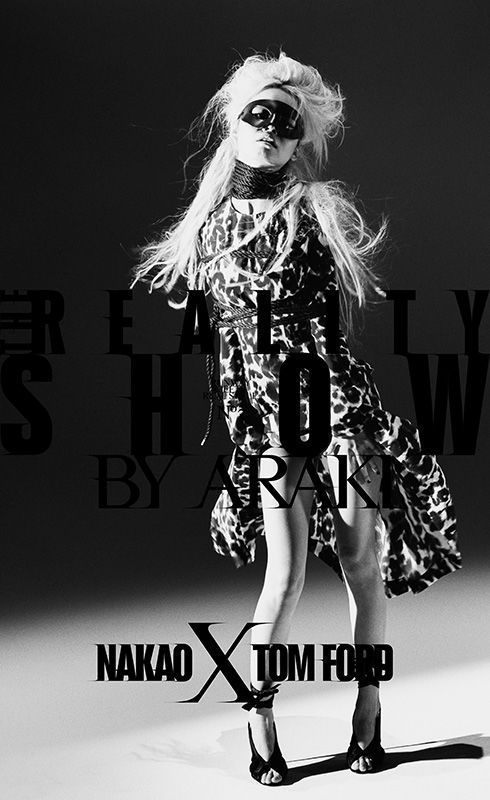

THE REALITY SHOW

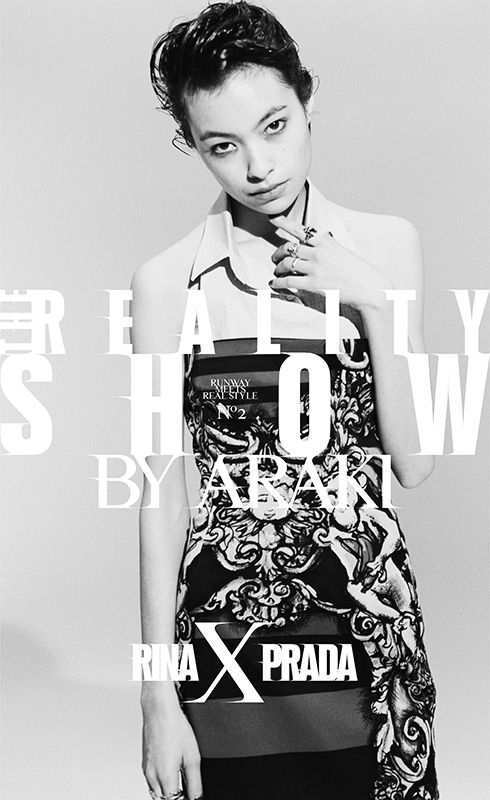

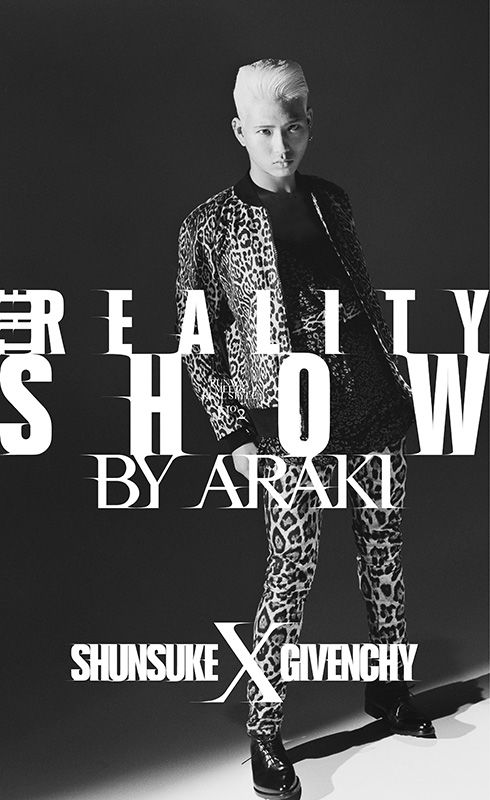

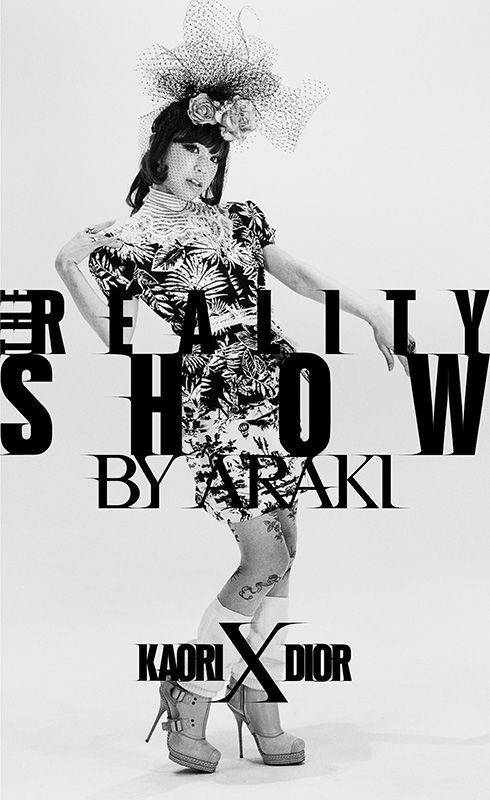

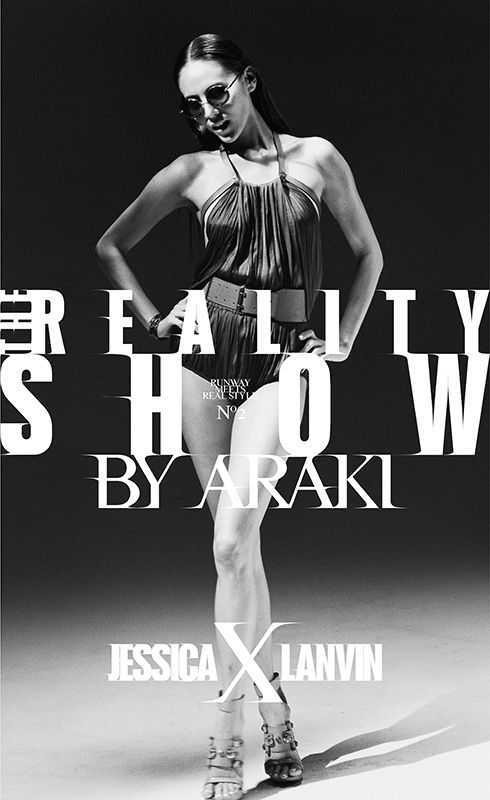

This publication gives Japanese fashion icons the chance to create their own styles with pieces from the world’s leading mode houses. The concept is “coming down from the runway to real life.” Leading Japanese photographer Araki Nobuyoshi shot the images for the second issue.

Clockwise from top left: actress Mizuhara Kiko wears Balenciaga; artist Nam Hyojun in Yves Saint Laurent; painter Matsui Fuyuko in Louis Vuitton; members of the band Plasticzooms sport Jil Sander; model Maaya in Chloé; Nakao, an office worker, wears Tom Ford; model Jessica Michibata in Lanvin; boutique manager Kaori in Dior; Shunsuke, a student, puts on Givenchy; and model Ōta Rina wears Prada.

(Based on an interview by Yata Yumiko. Interview photos by Igarashi Kazuharu.)

(*1) ^ Kosode were short-sleeved garments worn in the Heian period (794–1185) that were the precursor to the modern kimono.—Ed.

Tokyo gyaru fashion photography street fashion Harajuku Bruce Weber Paris Comme des Garçons Yamamoto Yoji Kawakubo Rei goth subculture