Matsuri Days (3): A Guide to Hakata and the Yamakasa Festival

Fukuoka: The Ancient Gateway to Japan

Guideto Japan

Society Culture Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Closer to Seoul than Tokyo

Kyūshū is the closest of Japan’s four main islands to the Asian mainland. Fukuoka, its largest city, is as near to Seoul as it is to Osaka (500 km)—and much closer to either than it is to Tokyo, roughly 1,000 km away (the same distance as Shanghai). Modern technology has shrunk these distances to the point where they hardly seem to matter. But in the days when slow-moving and disaster-prone ships were Japan’s only link to the outside world, Fukuoka’s proximity to the continent gave it a number of unique advantages. Today, Fukuoka is just one hour and 45 minutes by plane from Tokyo, but it retains many traces of its historical links to the cultures of China and the Korean Peninsula.

About Fukuoka City

A view of Hakata Bay and town from the 234-meter-tall Fukuoka Tower.

A view of Hakata Bay and town from the 234-meter-tall Fukuoka Tower.

The Gateway to Japan

The beautiful object in the picture above, intricately decorated with birds and flowers, is a porcelain pillow made in Tang China during the eighth or ninth century. Today, the pillow is one of a number of items on display in the Kōrokan historical museum in Hakata, which makes an ideal introduction to the ancient links between the city and the Asian mainland. The pillow’s fetching design and appealing decoration still catch the eye today, more than a thousand years after it was made. All those years ago, it must have been a precious object indeed, and surely belonged to a member of the local elite. But how did this ancient Chinese treasure come to rest here today, in the midst of a modern city in southern Japan?

The building that originally stood on this site, known as the Kōrokan, was one of three guesthouses that provided accommodation to overseas visitors during the early years of Japanese history. The other two were in Kyoto and Osaka. Fukuoka city official Yoshitake Manabu explains the importance of the site: “The Kōrokan was established here in Hakata for a very simple reason. In those days, this was the point of arrival for visitors from the Asian mainland. Diplomatic missions and traders visiting Japan from Tang China or Shilla [in modern Korea] would all land here first. For hundreds of years, Hakata served as the gateway to Japan.

The excavated finds at the Kōrakan include many items that were brought east along the Silk Road. These shards of a porcelain jar from close to modern Iran are still brilliantly blue today.

The excavated finds at the Kōrakan include many items that were brought east along the Silk Road. These shards of a porcelain jar from close to modern Iran are still brilliantly blue today.

The area to the east of the Kōrokan is reclaimed land. The shoreline used to pass directly through the point where the museum stands today.

The area to the east of the Kōrokan is reclaimed land. The shoreline used to pass directly through the point where the museum stands today.

Not far from the Kōrokan is the site of Fukuoka Castle, built for the feudal lord Kuroda Nagamasa in the early seventeenth century. Set into the floor of the visitor center today is a remarkably detailed relief map showing a bird’s-eye view of the local area as it would have appeared in the middle of the nineteenth century, before the Meiji Restoration that brought the feudal era to an end in 1868. The model makes it strikingly clear how the castle must have dominated the area, towering over the surrounding landscape of low-rise houses and streets. The castle was built on the same strategic site that once housed the Kōrokan.

The scale model of the castle town is remarkably detailed. A closer look reveals individual streets and houses, as seen in the view on the right.

The scale model of the castle town is remarkably detailed. A closer look reveals individual streets and houses, as seen in the view on the right.

Spiritual and Technological Lessons from the Mainland

Until modern times, visitors to Korea and China invariably returned to Japan via Fukuoka. One of the things they brought back with them was Buddhism. Numerous temples survive in the area around Hakata Station to this day, among them some of the oldest in Japan. In ancient times, these temples and their gardens covered huge swathes of the local area. Even today, the tranquil grounds of these ancient retreats offer an oasis of peace and respite from the hustle and bustle of the modern city.

One major stop on any tour of Hakata’s temples is Tōchōji. This is the oldest of all the temples in Japan associated with Kūkai, founder of the Shingon (“true word”) sect of Buddhism and one of the most important figures in Japanese cultural history. Kūkai, also known as Kōbō Daishi, is believed to have founded this temple in 806 to pray for the success of his teachings after his return from China, where he studied the sutras and was initiated into the secrets of esoteric Buddhism. The wooden statue of a seated Buddha here is reputed to be the largest in Japan. In the temple grounds is a series of stone statues dressed in black-and-white patterned clothing. The statues depict “Jizō,” the Japanese name for the guardian deity of suffering souls, particularly those of people who died as children. According to the temple priest, it is a local tradition to dress up the statues like this every year during the Hakata Gion Yamakasa festival, “So that Jizō-sama can join in the festival too.”

Tōchōji in Hakata, one of the oldest temples in the country and home to Japan’s largest wooden sitting Buddha.

Tōchōji in Hakata, one of the oldest temples in the country and home to Japan’s largest wooden sitting Buddha.

A line of stone statues of Jizō dressed up for the festival.

A line of stone statues of Jizō dressed up for the festival.

Just across the road from Tōchōji is Shōfukuji, another venerable temple and an important landmark in the development of Buddhism in Japan. Dating back to 1195, this claims to be the first Zen temple ever built in Japan. It was founded by Myōan Eisai (also known as Yōsai), who studied Zen Buddhism in China and was the first to introduce the teachings of the sect to Japan. He built his temple here after his return, on land granted to him by Minamoto no Yorimoto [1147-99], the first shōgun and an important early supporter of Zen Buddhism. Inside the temple grounds is one of Kyūshū’s few dedicated zazen (Zen meditation) halls. “Young monks still come here to practice Zen meditation today, just as they did when the temple was built,” says a worker in the temple’s office. The zazen experience is open to members of the general public—but it takes commitment! Students are required to sign up for at least a year of classes. There are currently between 30 and 40 people enrolled in the temple’s meditation courses. With their well-tended gardens and bountiful greenery, the temple grounds are a popular retreat for workers from nearby offices in search of peace and tranquility.

People have been studying Zen meditation here for nearly 1,000 years.

People have been studying Zen meditation here for nearly 1,000 years.

The last temple on our journey was Jōtenji, also close by in Hakata’s historic district. Jōtenji is famous for a collection of monuments proclaiming this to be the spot where a number of foods first arrived in Japan from the mainland. These include many that have been mainstays of the Japanese diet ever since: udon (thick wheat noodles), soba (buckwheat noodles), and manjū (a kind of sticky confection made from rice, flour, and bean paste). Many other areas of Japan claim to be the birthplace of udon. What makes this temple’s claim different are its associations with the thirteenth-century Buddhist monk and scholar Shōichi Kokushi, widely believed to have brought back techniques for milling wheat into flour after his periods of study in China. It was these new methods that enabled flour to be produced easily and in large quantities, making foods like udon available to ordinary people for the first time.

Hakata-Ori Weaving

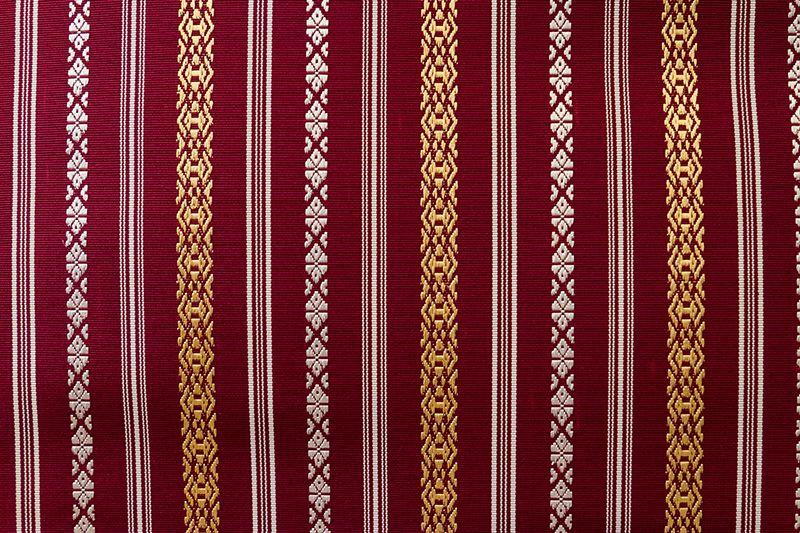

Many other items of continental culture entered Japan through Hakata. For instance, the city is also famous for its arts and crafts, many of which originated in the continent. Hakata’s famous textile tradition, known as Hakata-ori, dates back to a young tradesmen who accompanied Shōichi Kokushi to Song China and brought knowledge of Chinese weaving techniques back with him to Japan. The most famous of all local fabric patterns is kenjōgara, which was originally a special high-quality silk woven as an official gift for “presentation” (the meaning of the word kenjō) to the Tokugawa shōguns.

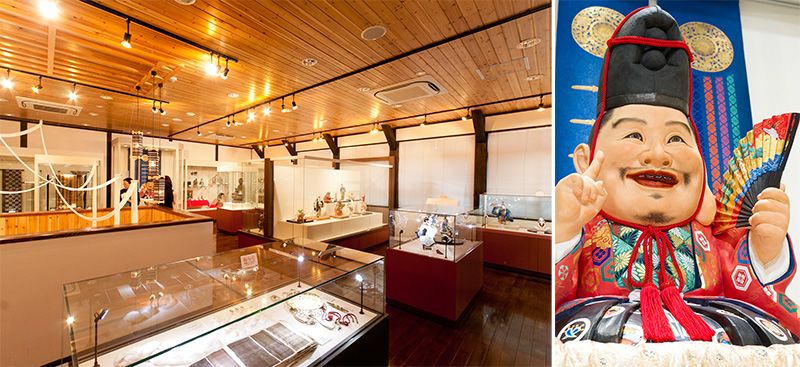

Hakata is also famous for its dolls. The god of good fortune shown here was specially made for the museum.

Hakata is also famous for its dolls. The god of good fortune shown here was specially made for the museum.

Not far from the temples, the Hakata Traditional Craft Center displays some of Hakata’s best traditional arts and crafts. Naturally, Hakata-ori is one of the main exhibits. “Hakata-ori is prized for the softness of its silk. This makes Hakata-ori the fabric of choice all over Japan for the obi sash worn with a traditional kimono,” says staff member Sakaguchi Yūri. Each of the elements used in the kenjōgara pattern has a special significance. The intricately woven lines use votive items found on a Buddhist altar as a motif. Thicker lines are thought to represent parents, while the thinner lines are compared to children. “Where the thicker lines surround the thinner ones, we say that the parents are watching over their children,” says Sakaguchi. “When it’s the other way round, we say the children are now looking after their parents in their old age.” The colors of the designs also draw on Chinese cosmological and philosophical traditions. Purple represents virtue; blue is for benevolence; red stands for ritual propriety; yellow for honesty; and navy blue for wisdom.

Some of the traditional weaving machines are works of art in their own right.

Some of the traditional weaving machines are works of art in their own right.

Visitors can watch Hakata-ori weavers at work at the Hakata Machiya Furusato Kan, a museum dedicated to the living history and traditions of the local area. The museum stands in a renovated traditional building that originally served as the living quarters and workshop of a Hakata-ori weaving family around the turn of the last century. One of the weavers is Takiguchi Ryōko, a young woman who left her job as an office worker to fulfill her dream of working in arts and crafts. “The large number of vertical warp threads used in the cloth is one of the distinctive qualities of Hakata-ori,” she explains. ”It’s the interplay between the warp and the weft that creates these beautiful patterns.” Visitors have the opportunity to try their hand at weaving a cloth of their own. But it would take many years of painstaking practice to attain anything like Takiguchi’s marvelous dexterity and mastery of her craft. Thanks to the dedication and skills of Takiguchi and others like her, Japan’s craft traditions have a bright future in Hakata, where so many of them began.

(Originally written in Japanese. Photographs by Kusano Seiichirō.)tourism Kyūshū China Zen Korea mainland festival Hakata Fukuoka continent weaving