Matsuri Days (2): Nebuta Matsuri

“Nebuta Baka” Festival Fever in Aomori

Guideto Japan

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

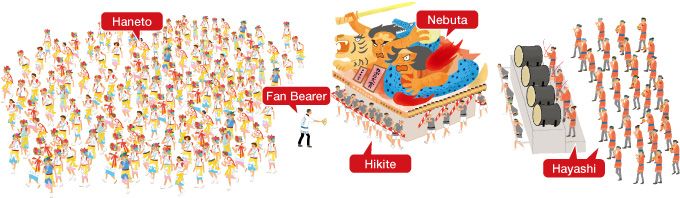

Click on the different parts of the image above to jump to the matching section.

As the capital city of the northernmost prefecture on Japan’s largest island, Aomori is normally a cool, quiet kind of place. But temperatures come to a boil in early August every year—and not just because of the summer heat. The colorful Aomori Nebuta Matsuri, which takes place between August 2 and August 7, is one of the largest festivals in Japan, attracting crowds of well over a million people.

Unlike many of Japan’s other famous festivals, Nebuta is not associated with any particular religious ceremony or temple. A spokesperson at the Aomori Prefectural Museum explains the festival’s origins as follows.

“For centuries, there has been a folk tradition of cleansing the spirit by passing impurities into dolls or paper lanterns. This was especially popular around the time of the midsummer Buddhist Bon festival, when the spirits of the dead are believed to return to earth. In the northern Tōhoku region, the tradition came to encompass not just spiritual cleansing but also ceremonies to get rid of the listlessness and physical fatigue typical of the summer months. The tradition became known as nemuri nagashi. Some theorize that the word ‘Nebuta’ comes from a corruption of nemuri nagashi.”

The region is home to a number of similarly named festivals featuring paper lanterns in a variety of shapes, including the human forms of Aomori’s Nebuta, the fan-shaped lanterns of the Neputa Matsuri in Hirosaki, and the taller, narrower forms of Goshogawara’s Tachi-Neputa.

Since the end of World War II, the lanterns of Aomori Nebuta have grown to gargantuan proportions. This year’s nebuta were an impressive five meters tall by nine meters wide. Each lantern consists of a solid wooden skeleton at its core. This provides the base for an intricate, hand-shaped wire frame that is meticulously covered in sheet after sheet of washi paper.

Inside the lantern, some 1,000 light bulbs are strung together, bringing the bright colors and ink-black lines of the lanterns to vivid life as they move through the city at night. Each lantern is mounted on a parade float that houses its power source—an electrical generator weighing as much as four tons.

The highlight of the festival comes when these huge floats—around 20 of them every year—take to the streets. This year, 22 floats took part.

The thrill of the Aomori Nebuta Matsuri comes from the excitement and passion of the local people for their festival, a passion known locally as “Nebuta Baka” (Nebuta mania).

A Chaos of Color

Creating the Floats: Takenami Hirō, Nebuta-shi

The main creative force behind each float is the nebuta-shi. The nebuta-shi oversees production of the festival floats from start to finish. He is responsible for coming up with the theme of the float, sketching the designs, building the skeleton and frame, laying the paper skin, drawing the black outline, and painting the colorful patterns. Until the 1970s the floats were put together by teams of local volunteers, mostly carpenters and amateur painters. But the increasing use of light bulbs and wire frames made it possible to depict faces in much more detail, and specialist nebuta-shi began to appear.

The main creative force behind each float is the nebuta-shi. The nebuta-shi oversees production of the festival floats from start to finish. He is responsible for coming up with the theme of the float, sketching the designs, building the skeleton and frame, laying the paper skin, drawing the black outline, and painting the colorful patterns. Until the 1970s the floats were put together by teams of local volunteers, mostly carpenters and amateur painters. But the increasing use of light bulbs and wire frames made it possible to depict faces in much more detail, and specialist nebuta-shi began to appear.

There are no formal structural drawings for the floats. The image in the mind of the nebuta-shi is everything. Takenami Hirō, who was responsible for three of the floats in the 2012 Nebuta Matsuri, says this is a big part of the appeal: “You have the freedom to express your ideas however you like,” he says. The use of bright, vibrant colors is one trademark of Takenami’s individual style.

Hiro Takenami’s “Aterui: Man of Tohoku” (Image courtesy of JR Nebuta Project)

Hiro Takenami’s “Aterui: Man of Tohoku” (Image courtesy of JR Nebuta Project)

During the long winter months, the local Tsugaru Region is covered in a heavy shroud of snow. Perhaps it was this environment and the hunger for color it bred that gave rise to the vibrant colors of a festival like Nebuta.

“When I’m developing a new float, I often start by choosing the main color,” Takenami says. “Take the ‘Aterui: Man of Tohoku’ float, for example, which I designed for Japan Rail. As soon as I started to think about the historical subject—a local military chief who led resistance against the central court in the Tōhoku area more than 1,000 years ago—the color red came to me right away. I thought flames would offer me plenty to work with in terms of incorporating red into the design, and gradually a mental image began to take form. But it doesn’t matter how attractive the color is—if we spread it too thick when we paint the float, the light won’t shine through. The trick is to make sure that the colors are at their best when they are lit up in the dark. Using wax helps control the transparency of the colors. The technique is a survival from the days when the floats were still lit with candles.”

During the festival parade, many people in the crowd will be looking on from a vantage point of 10 meters away or more. Taking distance and perspective into account is crucial.

A newly finished float is work of art in pure white. In the short time before the float is painted, its features are visible only as shadows.

A newly finished float is work of art in pure white. In the short time before the float is painted, its features are visible only as shadows.

“I’m constantly looking at things from the spectators’ perspective. What can I do to make the floats as impressive as possible to people looking up from street level? That’s when experience comes into play—how many nebuta have you seen over the course of your life?”

As a child, Takenami would wander transfixed around the Nebuta Koya, the large sheds where Nebuta floats are built and repaired. He got his first hands-on experience working on smaller floats for minor local Nebuta parades, working as a pharmacist while dreaming of building on a larger scale some day. Today, that dream is a reality. With a long stream of successes to his name, Takenami now regards his work as a nebuta-shi as his primary career.

As a child, Takenami would wander transfixed around the Nebuta Koya, the large sheds where Nebuta floats are built and repaired. He got his first hands-on experience working on smaller floats for minor local Nebuta parades, working as a pharmacist while dreaming of building on a larger scale some day. Today, that dream is a reality. With a long stream of successes to his name, Takenami now regards his work as a nebuta-shi as his primary career.

“I feel much more myself doing this than being a pharmacist. Even though I have to admit I still put my on white coat from time to time to earn a bit of extra money,” he laughs. “As a rule, most nebuta-shi have a regular day job to keep them going as they work on their floats. Even the most established nebuta-shi can’t depend on a steady income from their floats alone. But that doesn’t stop people from flocking to the work. It’s a sign of the fascination the festival holds over people, I guess.”

Takenami admits that his ambitions go beyond simply building floats. As well as working to nurture the next generation of nebuta-shi, Takenami longs to see the floats recognized not just as colorful elements of a festival parade but as works of art in their own right. To that end, he has founded the Nebuta Research Center, where he passes on the spirit and techniques of the art to a constant stream of aspiring youngsters hoping to become nebuta-shi themselves one day. Making the traditions and art of the festival better known overseas is another priority.

“Hungary made a big impression on me—the experience of setting these great lanterns of wood and paper in motion among the rows of heavy stone buildings . . . The local media treated the lanterns as “paper art” or “light art,” and were curious to know more about the use of bold primary colors in our designs. In Los Angeles, people are quite used to seeing electric-powered floats in lavish parades. So I was quiet taken aback to hear audiences responding with “oohs” and “aahs” when the float lights went on. Apparently they didn’t expect such a big lantern to actually light up. I think we should do more to share the delights of our nebuta floats with people around the world.”

Bringing the Floats to Life

Fan Bearer: Kushibiki Junji, Director of Sunroad Aomori

The Nebuta Grand Prize for 2011 went to the Sunroad Aomori group, who scooped the Float Driver and Haneto Prize as well. The Grand Prize is awarded primarily for the float itself, but also takes the group’s overall performance over the course of the festival into consideration, including float driving, haneto (dancers), and hayashi (parade musicians). No matter how well-crafted a float a group brings to the parade, if the group cannot thrill the crowds, it won’t win the Grand Prize.

The Nebuta Grand Prize for 2011 went to the Sunroad Aomori group, who scooped the Float Driver and Haneto Prize as well. The Grand Prize is awarded primarily for the float itself, but also takes the group’s overall performance over the course of the festival into consideration, including float driving, haneto (dancers), and hayashi (parade musicians). No matter how well-crafted a float a group brings to the parade, if the group cannot thrill the crowds, it won’t win the Grand Prize.

Sunroad Aomori is a shopping center made up mostly of small local businesses that has participated in the festival for more than 30 years. Thanks to the group’s strong community ties and the work of leading nebuta-shi Chiba Sakuryū, the formidable Sunroad Aomori group finishes close to the top of the rankings every year. Director Kushibiki Junji manages the float driving group during preparations for the festival. He is also in charge of coordinating everything with the nebuta-shi, the hayashi, and all the other people connected to the festival.

Kushibiki holds the title of “fan bearer” during the festival parade, leading the movement of his group’s float. “For anyone who loves Nebuta, the ultimate goal is to become a fan bearer,” he says. “I’ve helped build floats; I’ve beaten the taiko drums; I’ve danced as a haneto; and I’ve pushed the floats as a hikite. But as a fan bearer, you’re guiding the movement of the floats, and wowing the crowds . . . That’s the greatest thrill of all.”

Chiba Sakuryū’s “The Glory of Oshu Hiraizumi; Aterui and Kiyohira” (Image courtesy of Sunroad Aomori)

Chiba Sakuryū’s “The Glory of Oshu Hiraizumi; Aterui and Kiyohira” (Image courtesy of Sunroad Aomori)

The most important of the fan bearer’s roles is to make the floats come alive. “On the big night, the most important thing is to lead the hikite in such a way that the audience gets the impression of a single fluid unity.”

Sunroad Aomori always casts high school students in the role of hikite.

“A hikite has to deliver sheer physical power. It’s a tough job for anyone over 30. Of course, college students have the muscles for the job too. But once you’ve tasted alcohol, the temptations of festival time can be too strong! That’s why it’s got to be high-schoolers. Besides, once you’ve experienced Nebuta in your youth it’s in your blood. Nebuta draws people back to Aomori every summer.”

Nebuta as a Family Affair

Mother and Daughter Hayashi: Fukuzaki Yumi and Karen

The hayashi musicians play one of three instruments: the taiko drums, the flute, or hand cymbals. Wakai Gyo is the leader of the Uminari Maruhanichiro Nebuta Group. “Hayashi play a vital role,” he says. “We are responsible for creating the music that stokes the fires of the festival. We’re very proud of our role.” Each group plays the same basic melody to accompany the traditional shouts. “But we can vary the rhythm to suit the theme. The theme of last year’s float was the newly opened Tōhoku Shinkansen extension to Aomori, so we played at a quicker tempo. This year it’s the Kongōrikishi [also known as Niō], the powerful guardian deities that stand guard at the entrances to Buddhist temples. So we’re playing with a weighty sound to reflect the awe and majesty of the gods.”

The hayashi musicians play one of three instruments: the taiko drums, the flute, or hand cymbals. Wakai Gyo is the leader of the Uminari Maruhanichiro Nebuta Group. “Hayashi play a vital role,” he says. “We are responsible for creating the music that stokes the fires of the festival. We’re very proud of our role.” Each group plays the same basic melody to accompany the traditional shouts. “But we can vary the rhythm to suit the theme. The theme of last year’s float was the newly opened Tōhoku Shinkansen extension to Aomori, so we played at a quicker tempo. This year it’s the Kongōrikishi [also known as Niō], the powerful guardian deities that stand guard at the entrances to Buddhist temples. So we’re playing with a weighty sound to reflect the awe and majesty of the gods.”

Whereas the role of hikite requires physical strength and is mostly filled by young men, the role of hayashi is filled by men and women of all ages. In this group, several generations of the same family play together, like Fukuzaki Yumi and her daughter Karen, who both play the flute.

Whereas the role of hikite requires physical strength and is mostly filled by young men, the role of hayashi is filled by men and women of all ages. In this group, several generations of the same family play together, like Fukuzaki Yumi and her daughter Karen, who both play the flute.

Karen, a high-school student, says she prefers hayashi practice to hanging out with her friends. She regularly attends hayashi practice with her mother.

“I danced as a haneto with Karen in my arms when she was about one year old,” her mother rememebers. “She used to sleep so peacefully, and didn’t seem to mind the noise of the hayashi at all. That’s when I knew she’d grow up to love the festival herself one day. Years later, when I decided to get more involved in Nebuta myself, I asked my daughter ‘How would you like to become a hayashi with me?’ She picked it up much quicker than me! We’re shooting for a group prize this year, so we definitely want to take part in the maritime procession(*1) this year!”

Helping Everyone Enjoy Nebuta

Nebuta Executive Committee Chair Wakai Keiichirō

Wakai Keiichirō, chairman of the Aomori Nebuta Executive Committee, has seen the festival from a number of perspectives over the years. “When I was young, I used to enjoy taking part in the festival as a haneto or hayashi. Nowadays, it’s watching other people enjoying the festival that brings me the most pleasure. The most important thing for any festival is that everyone has a good time. That’s my job: to make sure that people enjoy themselves, whether they are dancing as haneto or watching from the sidelines.

Wakai Keiichirō, chairman of the Aomori Nebuta Executive Committee, has seen the festival from a number of perspectives over the years. “When I was young, I used to enjoy taking part in the festival as a haneto or hayashi. Nowadays, it’s watching other people enjoying the festival that brings me the most pleasure. The most important thing for any festival is that everyone has a good time. That’s my job: to make sure that people enjoy themselves, whether they are dancing as haneto or watching from the sidelines.

“Actually, although the main events take place in August, the Nebuta gets underway in July with the “Kodomo Nebuta” (Children’s Nebuta) for pre-school, kindergarten and elementary school children. If the big floats of the major festival are like the Major Leagues, the Kodomo Nebuta is like the minors. By encouraging children to enjoy Nebuta from an early age, we hope to instill the spirit of Nebuta Baka in the next generation.”

No matter who you are, once you’ve tasted Nebuta for yourself, you won’t be able to resist. That’s the power of Aomori Nebuta.

(Originally written in Japanese. Photographs by Kodera Kei. Illustration by Akiba Akiko.)

(*1) ^ On the seventh and final day of the festival, each of the top five award-winning floats are lifted onto flat-topped boats and paraded around the harbor. During the grand finale of Aomori Nebuta some 10,000 fireworks are launched over the maritime procession.