Japan’s “Kurozu”: A Centuries-Old Vinegar Tradition from Kagoshima

Guideto Japan

Food and Drink Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The mention of mold normally evokes looks of disgust, but not so for Aspergillus oryzae. Also known as kōji-kin, this expert fermenter has since ancient times helped produce the likes of miso, sake, and soy sauce, all basic seasonings used in traditional Japanese cuisine. Recognizing its eminent role in Japanese gastronomy, the Brewing Society of Japan even declared kōji-kin Japan’s “national fungus” in 2006.

The celebrated mold is also a key component in brewing kurozu, an amber rice vinegar produced in Kagoshima Prefecture. For more than 200 years artisans in the town of Fukuyama, now part of the city of Kirishima, have crafted the mild-tasting vinegar by combining kōji-kin with rice and water in black ceramic jars and letting the mixture slowly ferment and mature under the sun.

A Time-Tested Process

Kurozu literally means “black vinegar,” a name derived from the dark tint of the liquid. The vinegar is famed for its flavor, a well-rounded acidic tang with a hint of sweetness, and is used to enhance the taste of dishes. Kurozu is also esteemed for its various health properties—Fukuyama locals claim that in early times, demand for the black ceramic jars of vinegar would skyrocket during outbreaks of illness.

The amber color darkens as the vinegar ages.

The amber color darkens as the vinegar ages.

Vinegar is one of the oldest fermented foods known to humankind, but producing it at high quality and in large amounts is no simple matter. Crafting a batch of kurozu is a gradual process requiring patience and diligence on the part of the artisans. After an initial fermentation period, the mixture is allowed to mature for up to six months. Waste products are then skimmed off the surface and the vinegar is left to mature and mellow for an additional two or three years. During this time, the kurozu darkens to a coffee-like hue as its distinctive flavor profiles deepen.

After initial fermentation comes a period of three to six months of maturation in the jars. After this, waste products are skimmed off the surface and the vinegar is allowed to age.

After initial fermentation comes a period of three to six months of maturation in the jars. After this, waste products are skimmed off the surface and the vinegar is allowed to age.

There is no kurozu factory in Fukuyama. Instead, visitors to this hillside village find expansive lots overlooking Kagoshima Bay that are packed with row upon row of black jars of kurozu aging in the sun.

Jars of kurozu stretch into the distance. The size and dark tint of the vessels, meant to maximize heat absorption and retention, have remained the same for two centuries; they are even placed in rows stretching north to south to ensure they can all receive both morning and evening sunshine.

Jars of kurozu stretch into the distance. The size and dark tint of the vessels, meant to maximize heat absorption and retention, have remained the same for two centuries; they are even placed in rows stretching north to south to ensure they can all receive both morning and evening sunshine.

A Self-Contained System

Brewing rice vinegar is relatively straightforward. It first involves mixing and fermenting basic ingredients to create sake, after which special bacteria converts the alcohol into acetic acid, a primary component of vinegar.

While most commercial vinegars are produced under factory conditions with careful control of every aspect from the exact strains of mold used to the temperature from moment to moment, kurozu is handcrafted in the open using specially designed 60-centimeter tall ceramic jars. Nature is an essential element in the brewing process. The village enjoys plenty of sunshine and an average temperature of 18 to 19 degrees Celsius, warm enough to keep winter frost from being a serious problem. The surrounding hills also provide abundant fresh, clean water essential for making kurozu.

The brewing season gets underway in April. Artisans first add the raw materials—kōji-kin, followed by steamed rice, and then water—to the handcrafted ceramic jars. A final layer of kōji mold is carefully sprinkled on the surface of the mixture, and the containers are capped and sealed.

An artisan adds a final layer of kōji-kin to keep out any unwanted microbes that might disrupt the fermentation process.

An artisan adds a final layer of kōji-kin to keep out any unwanted microbes that might disrupt the fermentation process.

Inside the jars, kōji-kin gets to work breaking down starch from the steamed rice into sugar, which yeast living on the inside walls of the vessel then converts into alcohol. After about a month, the jars give off a fine bubbling sound and pleasant aroma of sake. After around the third month, the surface layer of kōji-kin sinks to the bottom of the vessel and the unmistakable scent of vinegar can be detected, indicating that the transformation to kurozu is complete.

An artisan puts kōji-kin into ceramic jars, along with steamed rice and water. The fermenter is made by hand by spreading mold spores on steamed rice and allowing it to sit for three days in a special temperature-controlled room.

An artisan puts kōji-kin into ceramic jars, along with steamed rice and water. The fermenter is made by hand by spreading mold spores on steamed rice and allowing it to sit for three days in a special temperature-controlled room.

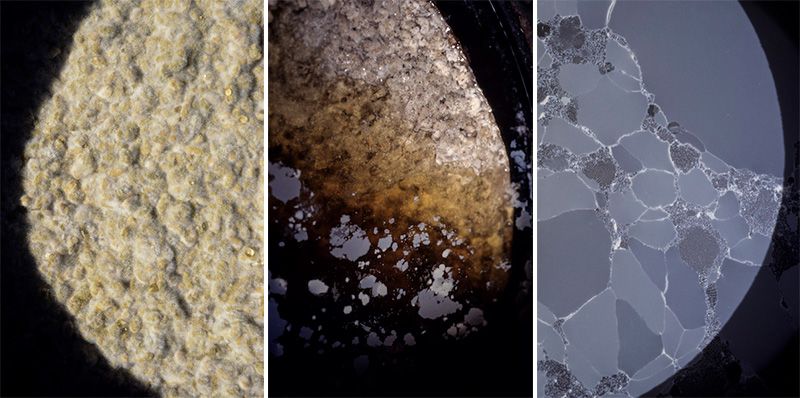

From left to right: After a month, bubbles on the surface indicate that fermentation is in full swing. After three months, acetic acid fermentation progresses and the surface layer of kōji-kin sinks to the bottom. By the fourth month, a thin layer of acetic acid bacteria forms; when it disappears, the initial fermentation process is finished.

From left to right: After a month, bubbles on the surface indicate that fermentation is in full swing. After three months, acetic acid fermentation progresses and the surface layer of kōji-kin sinks to the bottom. By the fourth month, a thin layer of acetic acid bacteria forms; when it disappears, the initial fermentation process is finished.

Artisans check the jars daily to ensure that everything is progressing as it should. Going from container to container, they listen for sounds of fermentation, check the clarity of the liquid, and even taste and smell contents looking for minor differences in quality.

“The jars can house beneficial as well as harmful microbes,” explains one artisan. “If the good kind wins, then you end up with a great batch of vinegar.” Helping acetic acid bacteria transform sake into vinegar involves stirring the jars with bamboo poles to keep the mixture oxygenated. If it looks like harmful bacteria are getting the upper hand, artisans will quickly add mature vinegar in an attempt to turn the tide. Although demanding, the constant doting is necessary for crafting high-quality vinegar that can proudly be proclaimed as kurozu.

A final component in the brewing process is temperature. Microbes like kōji-kin and yeast require a warm environment to thrive, and the kurozu jars—called aman in the local Kagoshima dialect—have been carefully crafted to this end. Early artisans worked out the optimal size, shape, and color of the containers to keep contents at an ideal temperature. Two centuries on, the vessels continue to serve their purpose with aplomb.

Brewing vinegar by all-natural means is a laborious, time-consuming process. But as long as the sun shines on Fukuyama, you can be assured that artisans in the town will be crafting kurozu in the traditional fashion.

Dusk falls on Fukuyama as the volcano Sakurajima lazily breathes smoke into the skies above Kagoshima Bay.

Dusk falls on Fukuyama as the volcano Sakurajima lazily breathes smoke into the skies above Kagoshima Bay.

(Originally published in Japanese. Text by Mutsuta Yukie. Photos by Ōhashi Hiroshi. Banner photo: Artisans in Fukuyama start on a new batch of kurozu.)