Revisiting Scenes of Timeless Nostalgia

The Nostalgic Taste of "Dagashi" Snacks

Culture Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Most Japanese people over 40 get a bit nostalgic at the mention of the inexpensive candy and snacks called dagashi. It brings back memories of the economic boom years, stretching from the 1950s to 1970s, when kids often stopped by the local candy shop and lined up to buy a little toy or a candy that gave them a chance to win a prize. For younger kids these shops were the place to hang out after school.

There aren’t nearly as many dagashiya as there were in those boom years, but you can still find some in places. It is also possible to buy dagashi candy and snacks on the Internet or through mail order.

Tokyo’s Oldest Dagashiya

The current building housing the Kami-kawaguchiya shop selling “dagashi” was built in the late nineteenth century, and survived both the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 and the bombardment during World War II (Address: 3–15–20 Zōshigaya, Toshima-ku, Tokyo; closed on rainy days)

The current building housing the Kami-kawaguchiya shop selling “dagashi” was built in the late nineteenth century, and survived both the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 and the bombardment during World War II (Address: 3–15–20 Zōshigaya, Toshima-ku, Tokyo; closed on rainy days)

Kami-kawaguchiya is a dagashiya located on the grounds of Tokyo’s Kishibojin Shrine—a three minute walk from Kishibojin-mae station on the Toden Arakawa streetcar line. The shop has been selling candy for around 230 years, since opening way back in 1781. Uchiyama Masayo, who currently runs the shop, is its thirteenth owner. Initially the store sold citrus fruit candy drops, but in the mid-1950s, when the ingredients became hard to obtain, it began to sell a wider variety of dagashi. The shop that appears in the animated film Omoide poro poro (Only Yesterday), produced by Studio Ghibli, was modeled after Kami-kawaguchiya.

Uchiyama explains the array of dagashi at the front of her shop: “One popular item is our dried squid. Actually, because of the high price of squid, the dagashi makers use dried cod and add squid flavoring, which makes it affordable for children at just ten yen a piece. Another popular offering is our win-a-prize candy. Children that visit a shop like mine are often buying something they want on their own for the first time. They spend a lot of time thinking over their purchase, and it’s an exciting, fun time for them.”

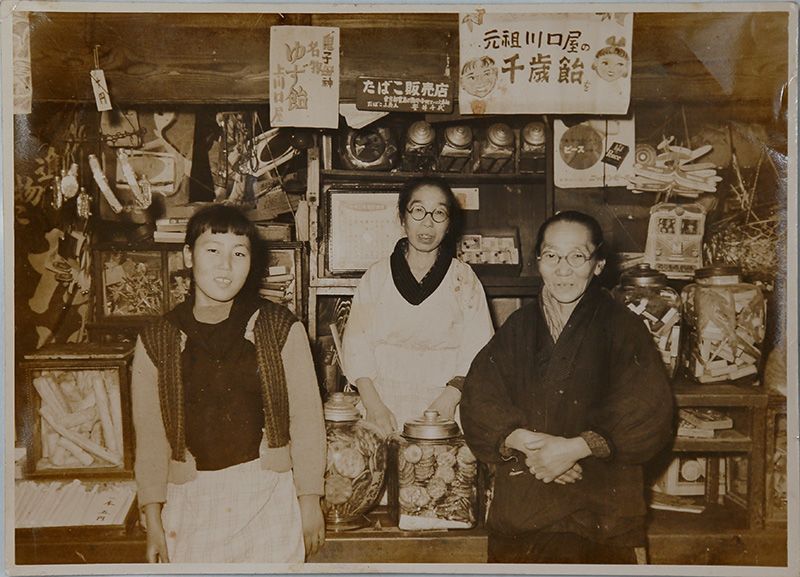

A photo of Uchiyama Masayo (left) back in 1954, with the twelfth owner Yasui Chiyo (center).

A photo of Uchiyama Masayo (left) back in 1954, with the twelfth owner Yasui Chiyo (center).

Uchiyama Masayo today, more than 50 years later, still earnestly selling “dagishi” at Kami-kawaguchiya.

Uchiyama Masayo today, more than 50 years later, still earnestly selling “dagishi” at Kami-kawaguchiya.

Every generation has its own image of dagashi, but the best-loved snacks overall are kinako ame (candies coated with soybean powder), dried plums, thin crackers brushed with sauce, and sweets such as soda-flavored ramune candy or the brown-sugary snack fugashi made of gluten.

A girl stopping by the dagashiya with her grandmother wins a prize!

“Perennial favorites at my shop are plum jam and sauce-coated crackers,” Uchiyama explains. “Back when I was a child, chocolate was a luxury, but these days kids can buy a piece for just ten yen. In all, we have around 100 different kinds of candy and snacks available. One thing that hasn’t changed is the smiles on the faces of children making their selection.” But she looks a bit sad as she points out how there are fewer children these days, and children spend less time playing with their friends on weekdays. Parents often take their kids to dagashiya on weekends, and the adults are often the ones whose eyes are sparkling most when they see all the items on display.

A sour plum soaked in a syrup that turns your tongue red.

A sour plum soaked in a syrup that turns your tongue red.

The crunchy, Cheeto-like snack Umai-bō.

The crunchy, Cheeto-like snack Umai-bō.

Candy coated with soybean powder is a long-standing favorite. If the end of the stick is red, you win another piece.

Candy coated with soybean powder is a long-standing favorite. If the end of the stick is red, you win another piece.

New Dagashi Trends

Inokuchi Nobukatsu, the president of the dagashi retailer Inokuchi Shōten, tells us that his company currently handles around 500 different types of dagashi, generally priced between ¥10 and ¥100.

When Japan’s economy was booming, dagashi were looked on as “old fashioned” and thought to be on the road to extinction. Now the old snacks are back in the limelight. With the country facing an uncertain future, adults (especially the elderly) feel nostalgic about the bygone era that dagashi reminds them of.

“Some Japanese living overseas are making an effort to introduce dagashi and classic Japanese toys to people in foreign countries, and we are seeing an increase in orders from overseas,” Inokuchi notes. His shop is making an active effort to expand its overseas sales channels, using its Facebook page to appeal to Japanese living abroad.

There are some new developments as well when it comes to dagashi. There has been an increase in dagashi stores designed to have the retro feel of the Shōwa era (1926–89). There are also quite a few dagashi bars that have opened where customers can enjoy their favorite old snacks from childhood, or standard dishes from past school lunches, along with an alcoholic drink. And at school festivals replica dagashi shops are often set up. The demand for dagashi to be handed out as gifts at wedding events and other parties also seems to be on the rise.

There are fewer dagashiya these days in Japan, but there are still around 50 of these shops in Tokyo alone. Each shop has its own special items, such as inexpensive coin-operated games, summertime refreshments like shaved ice, or hot snacks in winter.

Adults have as much fun as kids when they see the candies and toys lining the shelves of a dagashiya. It brings back childhood memories of the anticipation they felt before making a purchase, or the excitement that comes with choosing the candy with a lucky prize. Visiting a dagashiya is a way for adults to recall those feelings they had as kids, and also share that same joy with their children or grandchildren.

(Photographs by Yamada Shinji.)

What is dagashi?

During the Edo period (1603–1868), the more expensive types of candy, made with white sugar, were called jōgashi. In contrast, the cheaper candies made from coarse grain or starch and consumed by the common people were called dagashi. The types of dagashi that people still eat today were mostly created after World War II. Because dagashi were intended for young children, candy makers came up with various ways to keep prices low, such as selling individual pieces of candy or gum. The shops that sell dagashi, called dagashiya, commonly offer such items as spiced or sweetened dried seafood; candy made from starch- or rice-based sweeteners; and processed foods with a long shelf life such as colored or seasoned fruits of vegetables. Dagashiya were popular among kids for offering a wide selection of low-priced items as well as raffles and candies with chances to win prizes. The stores could be found everywhere in Japan until the 1980s, but began to disappear as snack makers diversified their product lineups and convenience stores increased in number.

Snacks in an old glass container

“Castella” sponge cake on a stick

Milk thin crackers and brown-sugary “fugashi”

“Super Cola” gum and other items

“Ramune” candy in a plastic bottle

food children Dagashi candy nostalgia toys snacks Shōwa retro