“Cool Traditions” Stay in Tune with Modern Life

Modern-day Artisans Carry On the “Ukiyo-e” Tradition

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Since the nineteenth century, the West has been fascinated by the delicate lines, imaginative compositions, and beautiful colors of Japanese ukiyo-e (literally “pictures of the floating world”) woodcut prints. In Edo period (1603–1868) ukiyo-e were a part of daily life, serving as a means of communication, entertainment, and teaching aids at private educational institutions called terako-ya. In Europe they had a huge influence on the fine arts.

Today, however, only a few artisans are capable of producing these exquisite ukiyo-e, which raises the question of whether the superb techniques of multi-colored woodcut printmaking will be passed on to future generations. Fortunately, the Adachi Institute of Woodcut Prints based in Tokyo’s Mejiro district is engaged in the reproduction of ukiyo-e masterpieces by artists such as Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) and Kitagawa Utamaro (1753–1806), as well as the creation of original works, thereby preserving the techniques and traditions of this art form.

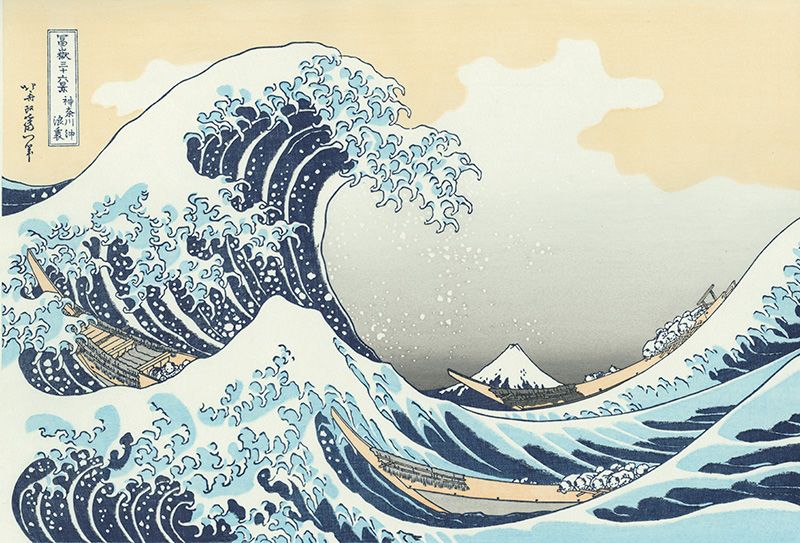

We toured the woodcut print studio at the institute, guided by its director Nakayama Meguri. There we saw carvers and printers using the same methods as the Edo-period artist Katsushika Hokusai to reproduce his masterpiece The Great Wave off Kanagawa from Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji.

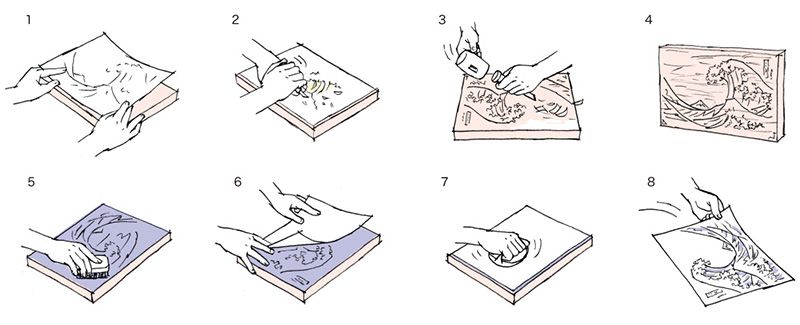

Process of reproducing an ukiyo-e woodcut print (1–4 is the carving and 5–8 the printing).

The design is pasted onto a woodblock (1), then the outline is carved with a small knife (2). After the surrounding wood is removed with a chisel (3), the key block is finished (4). During the printing stage, paint is applied to the woodblock (5), paper is placed on top of the block (6), and the paper is rubbed using a tool called a baren (7), thus completing the printing of one color (8). The finished ukiyo-e is produced by repeating this process for each color.

The design is pasted onto a woodblock (1), then the outline is carved with a small knife (2). After the surrounding wood is removed with a chisel (3), the key block is finished (4). During the printing stage, paint is applied to the woodblock (5), paper is placed on top of the block (6), and the paper is rubbed using a tool called a baren (7), thus completing the printing of one color (8). The finished ukiyo-e is produced by repeating this process for each color.

Woodcut Carvers Work with a Precision Measured in Millimeters

Carving requires extreme precision, so the workspace needs to be bright. A glass flask full of water hangs between the woodblock and a light bulb. When the light from the bulb hits the flask it is refracted in all directions and eliminates shadows from the surface of the woodblock, enabling the artisan to see the finest of lines.

Carving requires extreme precision, so the workspace needs to be bright. A glass flask full of water hangs between the woodblock and a light bulb. When the light from the bulb hits the flask it is refracted in all directions and eliminates shadows from the surface of the woodblock, enabling the artisan to see the finest of lines.

The atelier of the 69-year-old master carver Niinomi Morichika was enveloped in silence on the day of our visit, conveying his deep concentration. He was seated with his small knives, chisels, and the other tools of his trade near at hand.

The atelier of the 69-year-old master carver Niinomi Morichika was enveloped in silence on the day of our visit, conveying his deep concentration. He was seated with his small knives, chisels, and the other tools of his trade near at hand.

Niinomi uses a block of wood from a cherry tree that is hard and very fine-grained, and also resistant to swelling and shrinking due to changes in humidity. This makes it ideal for use in woodcut print production.

First, he applies rice starch paste to the board with the palm of his hand. Over the paste he then places a design drawn on extrememly thin washi paper. The paper is reversed, so that when the block is viewed from above the wave is on the right, yet will be on the left when printed.

In order to better see the outlines inked onto the reverse side of the paper Niinomi gently rubs it with his finger tips. Small pieces of paper break away as the paper disintegrates, exposing the ink outlines on the wood to assist his carving.

Strands of Women’s Hair Are Less Than a Millimeter Wide

Small cuts are made on both sides of the outlines with a small knife to bring them into relief (above). Next the surrounding wood is removed with a chisel (left). The aesthetic quality of the final woodcut print will depend on the skill of the carver. An experienced carver can accurately carve outlines of less then a milimeter in width, such as strands of beautiful women’s hair in prints by Utamaro; the process of carving lines for hair is known as kewari (separating out hair).

Small cuts are made on both sides of the outlines with a small knife to bring them into relief (above). Next the surrounding wood is removed with a chisel (left). The aesthetic quality of the final woodcut print will depend on the skill of the carver. An experienced carver can accurately carve outlines of less then a milimeter in width, such as strands of beautiful women’s hair in prints by Utamaro; the process of carving lines for hair is known as kewari (separating out hair).

This block carved with the outline of the design is known as the omohan (key block). A test print known as a kyōgōzuri is made with black ink to check the block and shown to the artist. The artist then uses red ink to indicate where the colors are to be placed between the lines. After that, the carver makes two guide marks known as kentō—an L-shaped one at the bottom right of the block and a flat one about a third of the way from the bottom left—to aid the placing of the paper on the block and ensure correct alignnment during printing.

28-year-old Kishi Chikura (front) saw Niinomi’s demonstration and decided to study the advanced skills used in the craft. Now he has finished his apprenticeship and is working as a professional woodcut carver.

28-year-old Kishi Chikura (front) saw Niinomi’s demonstration and decided to study the advanced skills used in the craft. Now he has finished his apprenticeship and is working as a professional woodcut carver.

The number of blocks produced by the carver depends on the number of colors in the design. These color blocks are known as irohan, and in the case of Hokusai’s Great Wave four are used. Only one side of the key block is carved to ensure it doesn’t warp during printing, but the color blocks are carved on both sides. Using these, eight layers of color are applied. During the Edo period it was required to keep costs to a minimum to produce ukiyo-e as profitably as possible. For that reason the number of colors was limited and generally around five blocks were used.

It takes about three weeks to carve all the blocks for Hokusai’s Great Wave. This meticulous and delicate task is achieved by accurate and deft use of the carver’s chisel. The level of skill required is truly remarkable.

The Secret of Bringing Out Color Is in the Printing

Next, a printer of over 40 years experience, Nakata Noboru (77), begins the work of applying each color in turn. First, liquid called dōsa is applied onto traditional washi paper. It is made with alum and hide glue, and prevents paint from bleeding into the paper.

Next, a printer of over 40 years experience, Nakata Noboru (77), begins the work of applying each color in turn. First, liquid called dōsa is applied onto traditional washi paper. It is made with alum and hide glue, and prevents paint from bleeding into the paper.

Usually the outline for an ukiyo-e is printed in black ink, but Hokusai’s famous print of Great Wave uses indigo. Initially, mineral and vegetable pigments were employed, but by the end of the nineteenth century artificial pigments were used to produce vivid colors. As far as possible, the artisans at the Adachi Institute use the same pigments as in the Edo period, dissolving them in water before use.

Printer Nakata Noboru at work.

Printer Nakata Noboru at work.

The printer wets the block using a horsehair brush to help it absorb the pigment. Then he begins the printing. He combines the colors to match the sample print, adds an amount to the woodblock (above), and spreads it carefully and thoroughly using the brush. Next he places the paper on the block using the kentō guide marks. He sits cross-legged in front of the printing table (known as a suridai) and rubs the paper using the baren. The table is tilted down and away from the printer to ensure that sufficient pressure is applied to the parts of the print further away.

The printer repeats this process for each color block, starting with the lighter colors then moving on to the darker ones. If the block dries out and contracts, the position of the two guide marks is adjusted to keep the colors correctly aligned.

The printing process takes considerable strength and for that reason it was traditionally a man’s work, although recently women have also begun to work as printers. The pressure from the baren pushes the pigment deep into the fibers of the paper creating rich and distinctive color effects. There are many other special techniques used, such as embossing and color gradations.

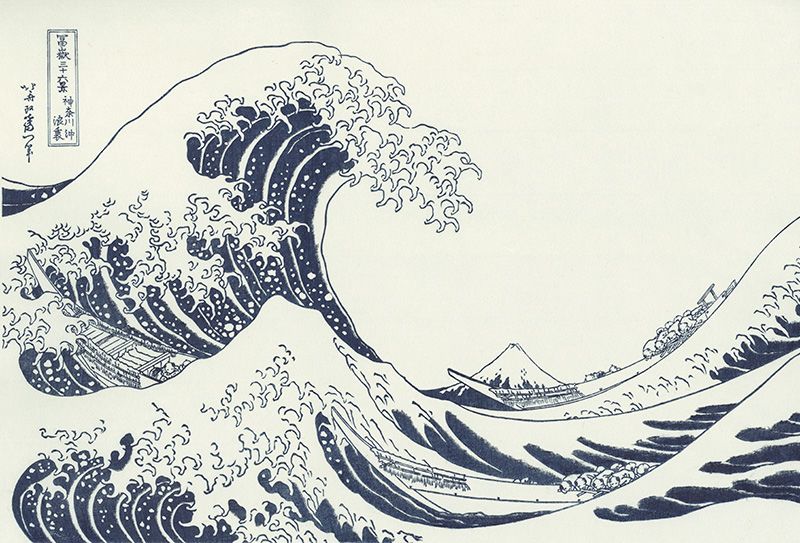

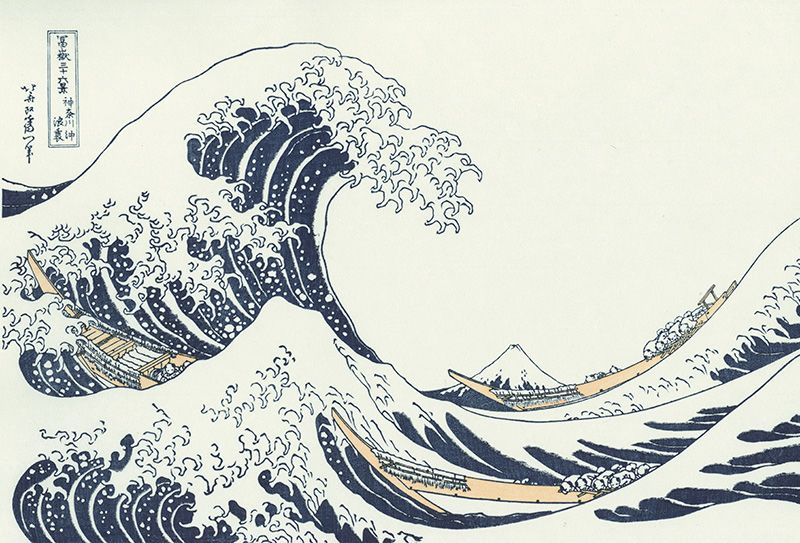

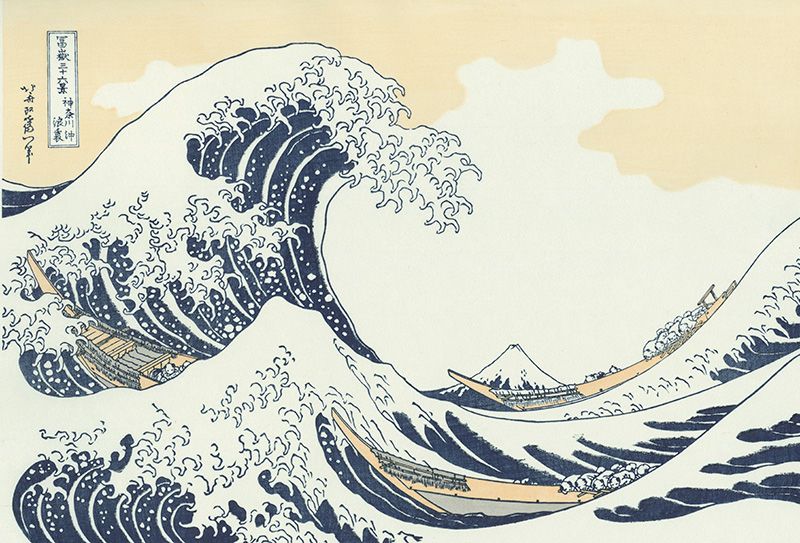

The printing process: first the key block is printed in indigo, then the colors are added, starting with the lighter colors before overlaying the darker ones.

Working to Keep Ukiyo-e Relevant to the Modern World

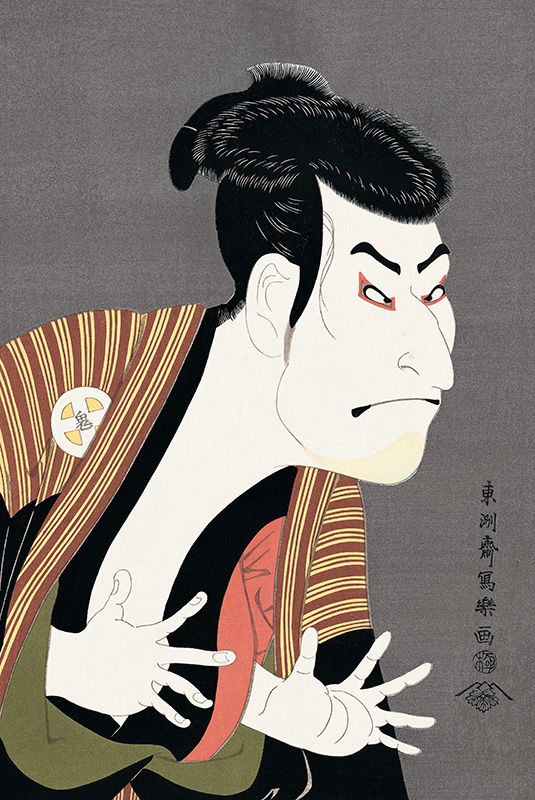

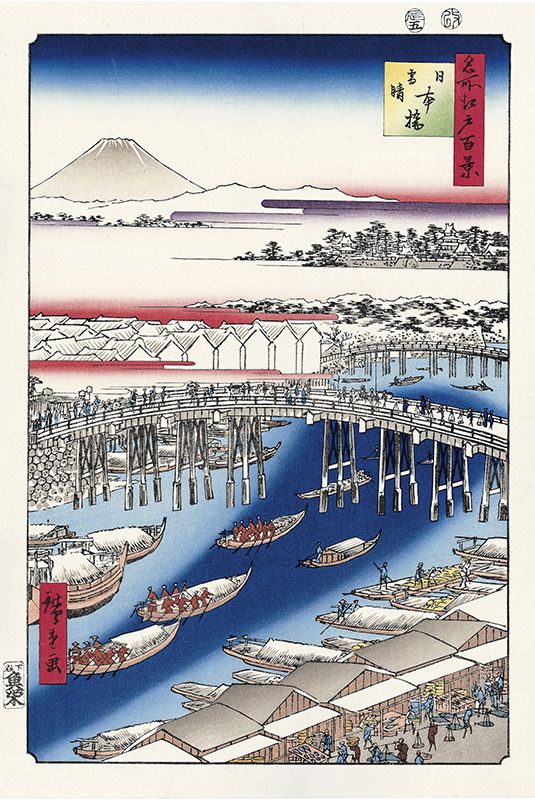

The Adachi Institute of Woodcut Prints opened its studio in Tokyo in 1928. Since then the institute has reproduced around 1,200 masterpieces by ukiyo-e artists such as Suzuki Harunobu (c.1725–70), Katsushika Hokusai, and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858), and also reproduced the entire oeuvre of 142 prints by Tōshūsai Sharaku (unknown).

The Actor Ōtani Oniji III as Edobei by Tōshūsai Sharaku.

The Actor Ōtani Oniji III as Edobei by Tōshūsai Sharaku.

Nihonbashi, Clearing After Snow, No. 1 in One Hundred Famous Views of Edo by Utagawa Hiroshige.

Nihonbashi, Clearing After Snow, No. 1 in One Hundred Famous Views of Edo by Utagawa Hiroshige.

Girl Blowing a Glass Toy from the series Ten Physiognomic Aspects of Women by Kitagawa Utamaro.

Girl Blowing a Glass Toy from the series Ten Physiognomic Aspects of Women by Kitagawa Utamaro.

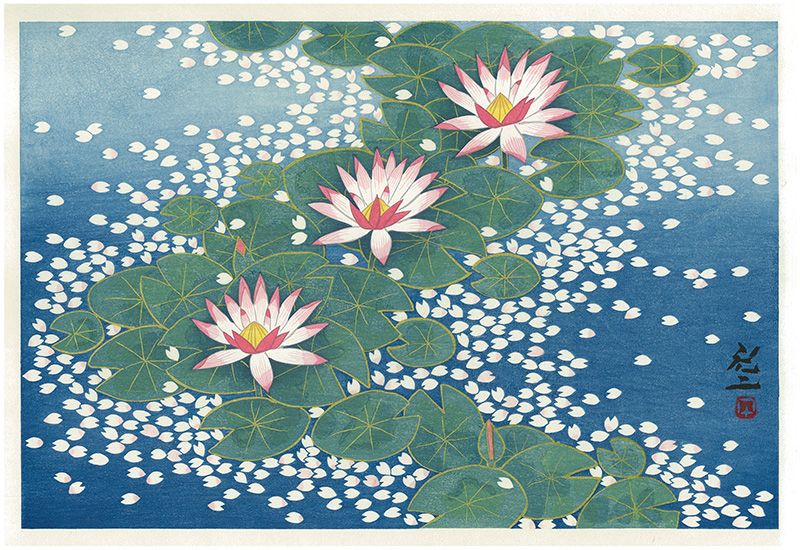

As well as faithfully reproducing works from the Edo period, the institute produces woodcut prints by twentieth century artists such as Yokoyama Taikan (1868–1958) and Hirayama Ikuo (1930–2009). It has also commissioned ukiyo-e drawings from modern artists such as Hiramatsu Reiji (b. 1941) and Yamaguchi Akira (b. 1969) to make original woodcut prints.

The 2013 multi-color woodcut print Haru (Spring) created from a design by the artist Hiramatsu Reiji

The 2013 multi-color woodcut print Haru (Spring) created from a design by the artist Hiramatsu Reiji

(© Hiramatsu Reiji / Adachi Institute of Woodcut Prints).

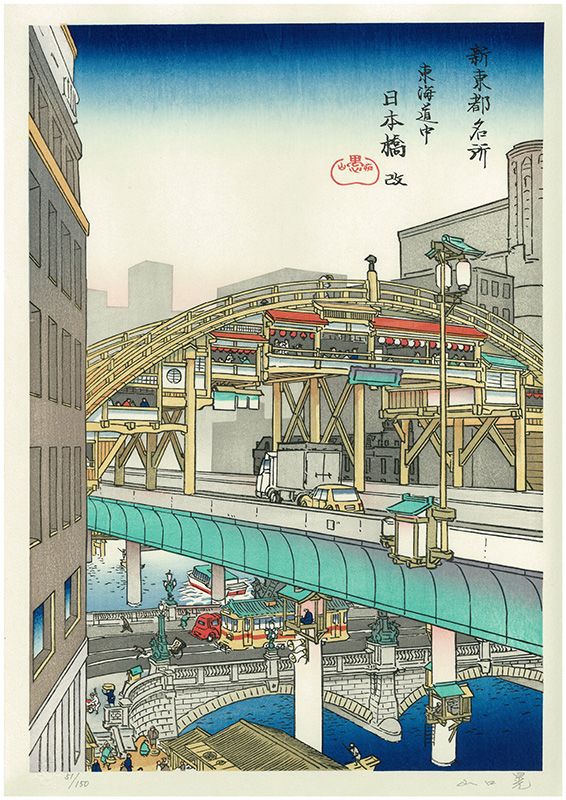

The 2012 multi-color woodcut print New Sights of Tokyo: Tōkaidō Nihonbashi Revisited created from a design by the artist Yamaguchi Akira (© Yamaguchi Akira / Mizuma Art Gallery /Adachi Institute of Woodcut Prints).

The 2012 multi-color woodcut print New Sights of Tokyo: Tōkaidō Nihonbashi Revisited created from a design by the artist Yamaguchi Akira (© Yamaguchi Akira / Mizuma Art Gallery /Adachi Institute of Woodcut Prints).

If the Adachi Institute of Woodcut Prints had not been created, the traditions of ukiyo-e stretching back to the Edo period might have disappeared. Although there are carvers and printers working as individuals elsewhere, the institute is the only place where artisans work alongside one another to make ukiyo-e and contemporary prints. Communication between the artisans is essential to preserving the advanced techniques employed and the quality of the artwork.

Artisans using actual woodblocks to make prints are actually in the minority in Japan, where various techniques tend to be used to make prints—such as lithography, silk screen printing, and digital printing. But ukiyo-e printed from woodblocks have a special quality; a warmth that stems from the traditional technique of pressing the water-based pigments into the washi paper to produce color.

The institute has set up a foundation to preserve the techniques of traditional woodcut printing and to support the professional development of artisans. Its aim is to pass down the wonders of woodcut prints to future generations. Nakayama, who is director of both organizations, expands on place of ukiyo-e in today’s society:

“Creating the sort of works that people today are interested in owning is crucial to the task of passing on ukiyo-e traditions to future generations. This requires the creation of new sales channels. We are trying to show people how ukiyo-e can enhance our contemporary lives, whether as a living-room decoration or as a gift for a friend overseas. Producing woodcut prints from works by contemporary artists is one important way of making ukiyo-e seem more contemporary in the twenty-first century.”

The "floating world" depicted in the Edo period woodcut prints was in fact the contemporary world of that time. Even though ukiyo-e is now seen as a traditional art form, it seems poised to retain its contemporary relevance by having its unsurpassed techniques passed down to future artisans capable of depicting the world around them.

(Originally written in French. Photos by Ōhashi Hiroshi and Illustrations by Izuka Tsuyoshi.)

art Tokyo kabuki ukiyo-e Japonisme Edo Shunga fine arts woodcut prints