“Cool Traditions” Stay in Tune with Modern Life

Nishijima “Washi”: Transforming Old Fibers into Specialty Art Paper

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

“The Paper Is an Essential Part of the Artwork”

Nishijima lies in the foothills of Japan’s Southern Alps in the town of Minobe, Yamanashi Prefecture. Craftsmen have been making washi paper here for more than 400 years. Blessed with abundant pure water from the upper reaches of the Fuji River, generations of local artisans have made washi from the mitsumata paper mulberry tree, mainly during the nonfarming season.

Having survived the tumultuous social changes over the past century and a half, the village’s artisans now specialize in ultra-fine paper for calligraphy and painting. The paper is extremely delicate and fragile, and ink written on the paper tends to blur and smudge. Papermakers here have their reasons for deliberately producing paper with these qualities.

Nishijima specializes in producing handmade washi art paper that is prized by painters and calligraphers.

Nishijima specializes in producing handmade washi art paper that is prized by painters and calligraphers.

In certain styles of calligraphy and ink wash (suiboku) painting, the artist’s aim is to produce a work that achieves a fine balance between sections of dark black ink, shadowy passages of muted washed-out gray, and the bright white blanks of the unpainted paper. “The paper is an essential part of the artwork,” says Kasai Shinji, a craftsman at Nishijima Washi, unfurling another sheet of fine art paper designed for Japanese-style painting. The paper is so thin it is impossible to peel single sheets from the dipping basin for drying.

“For a while after World War II it was difficult to obtain imported Chinese Xuan paper in this country,” explains Kasai. “That’s when we started making a version of it here in Nishijima to satisfy demand from artists and calligraphers. After a period of trial and error, we succeeded in coming up with a handmade washi version in the mid-1950s.” This experiment may have saved Nishijima’s washi makers from extinction. The new paper was well received and helped to bring life back to the village and its traditional craft. Six workshops produce handmade washi paper in the village today.

After it has been allowed to air-dry, the paper is immersed in water for half a day and then peeled off carefully, one sheet at a time, and dried again on a hot metal plate.

After it has been allowed to air-dry, the paper is immersed in water for half a day and then peeled off carefully, one sheet at a time, and dried again on a hot metal plate.

Bringing Old Paper Back to Life

The thick milky-white paper mash slops and churns in its bamboo suki-su. “When I was younger I used to be able to make a thousand sheets a day,” says Kasai. “Today, it’s about half that number.” Now in his eighties, Kasai skillfully whisks a huge sheet of fresh paper from the bath of pasty pulp. Nishijima paper is made using a unique process to ensure that the paper will soak up the ink in the right way and produce the desired effect.

“We use koshi [old paper] as the ingredients because the fibers are already quite worn and don’t contain as much oil as fresh paper.” Koshi is paper that has already been spread and dried once. In Nishijima, discarded edges of gasen-shi art paper, offsets from high-quality wallpaper, and paper that ripped during the drying process is given a new lease on life. “We boil the old paper in a big cauldron, add in Manila hemp and rice straw from Nishijima, then beat it with a machine to produce the soft cotton-like material that is then used as the material for making our paper.”

A mix is made from boiled-down strips of old paper, hemp, and rice straw, and a beater is used to produce the short-fibered mash from which Nishijima washi is made.

A mix is made from boiled-down strips of old paper, hemp, and rice straw, and a beater is used to produce the short-fibered mash from which Nishijima washi is made.

The precise length and thickness of the fibers and the exact composition of the mixture of ingredients, water, and starch have a decisive effect on the quality of the finished product. The mixture is also subject to subtle day-to-day variations in weather, temperature, and humidity. These are not measurable values—it takes the delicate touch and intuition of experienced artisans to get them all right.

The paper is then made by the nagashi-zuki method that has been used in Japan for centuries. Workers in Nishijima follow the same basic procedures as papermakers in other parts of Japan, but the sound as the paper is drawn from its bath of pulp is quite different. The reason is that workers push a pedal at regular intervals to release into the tub the precise amount of ingredients required for each sheet of paper.

Satisfying the Demands of Calligraphers

The conventional method involves scooping up the ingredients from the tub and shaking them gently, and then peeling off and drying one sheet of paper at a time. This can be very hard work when it is repeated dozens of times a day. In Nishijima, eliminating the need to scoop the paste from its tub has enabled even elderly artisans to continue working. Mixing the batch of ingredients all at once, moreover, helps to ensure consistency in the quality of the finished paper. Most workshops in Nishijima use this method, which was developed by Kasai’s forebears. Generations of artisans have come up with improvements to the traditional methods that have helped to keep the skills and craft alive in the community today.

The suki-geta is shaken to ensure that the materials are evenly mixed and of a uniform consistency (left). The suki-su is removed and freshly made paper moved to the drying area (center). Three hundred sheets are press-dried together (right).

The suki-geta is shaken to ensure that the materials are evenly mixed and of a uniform consistency (left). The suki-su is removed and freshly made paper moved to the drying area (center). Three hundred sheets are press-dried together (right).

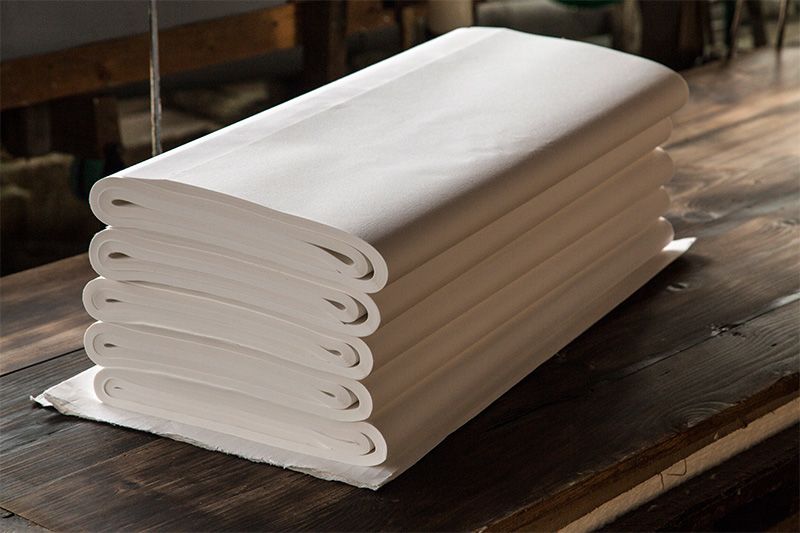

The drying method used in Nishijima is also quite distinctive. Around 300 sheets of fresh paper are put into a press together and the water wrung from them before they are left to dry in a well-ventilated place. This natural drying process takes from 10 to 20 days. Drying so many sheets together is much slower than drying the sheets individually. But because the paper is so thin and fragile, it is difficult to peel off single sheets individually without tearing them. Once they are fully dry, the paper is submerged in water again for half a day, and then individual sheets are peeled off and taken for final drying.

The fibers are too short to allow the paper to be peeled off one sheet at a time, so around 300 sheets are moved together to a well-ventilated place, where they are left to dry for 10 to 20 days.

The fibers are too short to allow the paper to be peeled off one sheet at a time, so around 300 sheets are moved together to a well-ventilated place, where they are left to dry for 10 to 20 days.

The paper is thin and soft, and a single sheet can be as long as 2.42 meters.

“If you grip it too hard, it tears. If it has too much water, that will cause it to break too, and if it’s too dry you can’t peel off the individual sheets,” says Kasai. Obviously, Nishijima washi needs to be handled with tender loving care. Using a hake brush, the craftsman slaps the sheet of paper on a hot steel plate for around a minute. While one side is being smoothed and stretched, the other side dries. Working ceaselessly, the craftsmen produce a constant procession of new sheets of fresh paper peeled one after the other.

To the untutored eye, the difference between handmade Nishijima washi and paper made using a machine is not easy to discern, even if you hold it in your hand and compare them side by side.

“You may not be able to tell the difference just by looking, but use a brush to write something and you’ll soon understand.” The feel of the brush against the paper is soft, with just a hint of resistance as the brush slides across the paper, followed by a beautiful bleeding of the ink. Calligraphers seldom choose any other paper once they have had the opportunity to write on this, says Kasai.

“We want to produce paper that will always meet the needs and desires of the user.”

Nishijima is a small village in the heart of the Japanese countryside where ancient traditions live on. By breathing new life into old pulp, its papermakers continue to respond to the exacting demands of artists and calligraphers.

The papermaking village of Nishijima lies on the banks of the Fuji River, surrounded by mountains and blessed with supplies of fresh water.

The papermaking village of Nishijima lies on the banks of the Fuji River, surrounded by mountains and blessed with supplies of fresh water.

(Originally published in Japanese on November 14, 2017. Interview and text by Mutsuta Yukie. Photos by Ōhashi Hiroshi. Banner photo: Workshops in Nishijima use a unique technique to make their paper. Pushing a foot pedal releases a mix of paper materials into the suki-geta where the paper is made. The reduced physical workload means workers even in their eighties can produce 500 sheets of paper a day.)