“Cool Traditions” Stay in Tune with Modern Life

Beyond the Great Wave: Hokusai’s “Deep Old Age” at the British Museum

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japan’s most famous artist, Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), had a long, protean, and astoundingly productive career. Before dying at the age of 88 he produced paintings, drawings, illustrated books, and, of course, the exquisite woodblock prints for which he is best known.

Yet, despite Hokusai’s status as Japan’s greatest artist and the fact that the British Museum acquired its first Hokusai print in 1860, the current exhibition is the first devoted solely to him there since 1948.

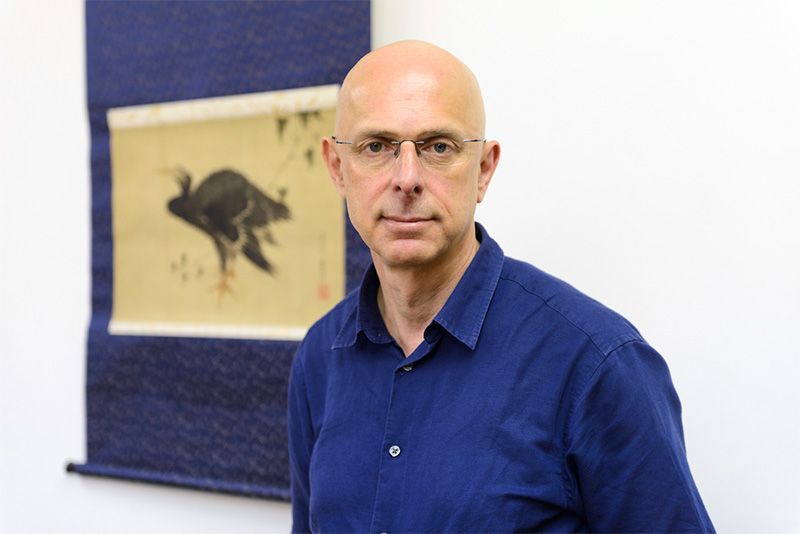

It was put together by Timothy Clark, head of the Japanese Section of the British Museum, and Asano Shūgō, a leading Hokusai scholar and director of the Abeno Harukas Art Museum in Osaka. (An exhibition of many of the same works will be held in Osaka this autumn.)

“I have been talking about doing this exhibition for twenty years,” says Clark.

Timothy Clark, head curator of the exhibition.

Timothy Clark, head curator of the exhibition.

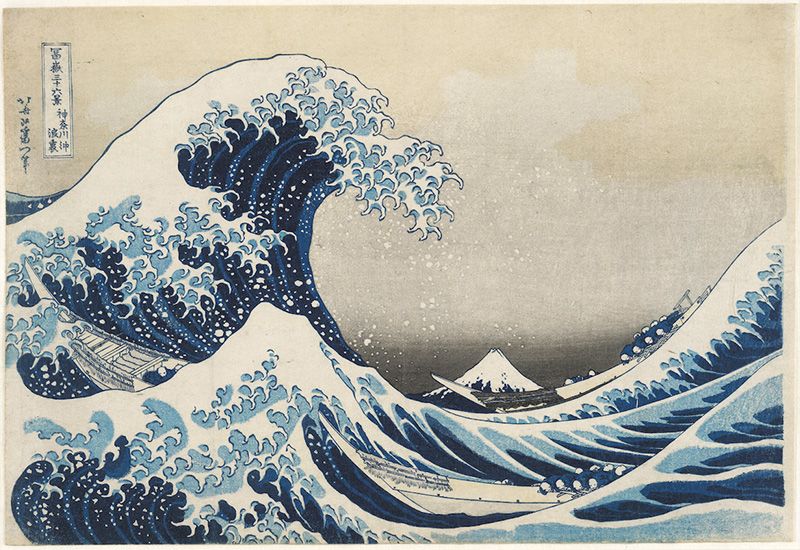

He chose the title Hokusai: Beyond the Great Wave in reference, of course, to Hokusai’s best known print—and in fact one of the most famous works of art from any place or time.

But the exhibition’s aim is also to introduce visitors to a wider range of the artist’s work. “The show is celebrating the Great Wave,” Clark says, “but then inviting visitors to journey into Hokusai’s deep old age.”

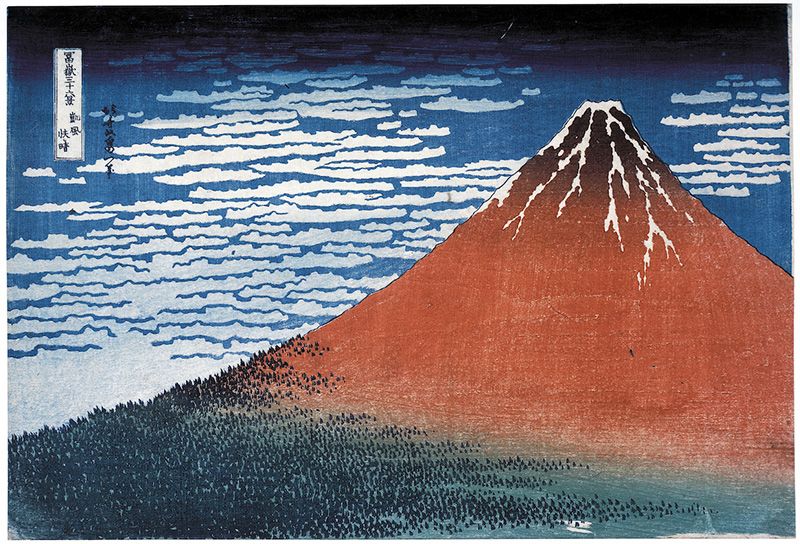

The exhibition focuses on the last three decades of Hokusai’s life, from the age of 60 (the beginning of a second life according to Japanese tradition) to his death at almost 90. And its title is reflected in its layout: The Great Wave off Kanagawa (1831) and the almost equally iconic print Red Fuji (formally Fine Wind, Clear Morning, 1831) are located close to the entrance; visitors physically venture past them into the world of Hokusai’s latter decades.

Ten Thousand Things

The exhibition is divided into two sections: Worlds Seen and Worlds Imagined. As the exhibition text explains, “Hokusai gave dynamic expression to the Japanese Buddhist belief that all phenomena—both animate and inanimate—have a spirit and are interconnected.”

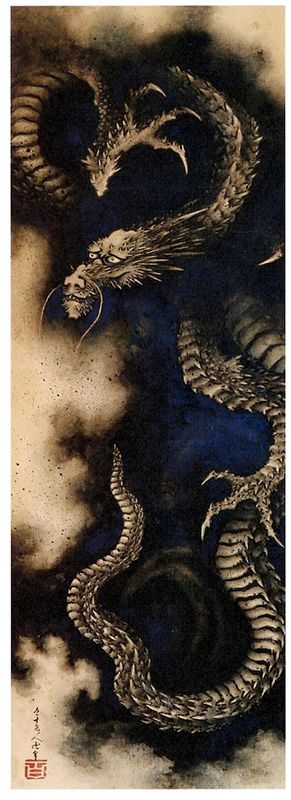

And Hokusai wanted to paint it all. His landscapes, such as his prints of Mount Fuji, are well known in the West, but he also portrayed imaginary dragons, ghosts, phoenixes, and Chinese lions.

“His ability to paint the things you can’t see is as powerful as those you can,” says Clark.

At the age of 75 Hokusai took on the name Manji, which can refer both to the Buddhist swastika and Chinese characters meaning “10,000 things.” It was a declaration of intent.

“There is nothing he doesn’t want to paint. It is incredible,” says Clark.

Hokusai’s determination to portray all he encountered was paralleled by his eagerness to absorb any artistic technique that might help him. Well before Hokusai exerted a profound influence on Western art via Van Gogh and the Impressionists, he himself was absorbing the European method of deep perspective.

That used to incredible effect in his famous Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, which was published when Hokusai was in his seventies and is today the series best known in Japan. It features two prints that are instantly recognizable. One is Red Fuji—accordingly, the autumn exhibition in Japan will be called Fuji o koete (Beyond Fuji).

Fine Wind, Clear Morning (Red Fuji) from Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (1831).

Fine Wind, Clear Morning (Red Fuji) from Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (1831).

The other is the Great Wave of the exhibition’s title, the iconic status of which is evident from the range of goods in the exhibition gift shop: mugs, pens, bags, trays, jigsaws, fridge magnets, lens cloths, and more.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa from Thirty-Six views of Mount Fuji (1831).

The Great Wave off Kanagawa from Thirty-Six views of Mount Fuji (1831).

Katie Turfkruyer, an automotive engineer from London, was visiting the exhibition with her boyfriend Michael.

“We were aware of the great wave print, but not that it was part of a large series focused on Mount Fuji,” she said. “Looking at the print, I saw a study of the difficulties humans can face in the natural landscape, even while that landscape is beautiful for humans to view.”

Hokusai’s wave decorates the museum entrance; Mount Fuji looms large inside.

Hokusai’s wave decorates the museum entrance; Mount Fuji looms large inside.

Many read the Great Wave as a portrayal of humans coming face to face with the awesome power of nature. And Hokusai did indeed produce the work after a time of particular hardship. His second wife had died, he was dealing with a wayward grandson’s debts, and he himself had recovered from a stroke.

Meanwhile, as a resident of Edo, he lived in a city where none could ignore nature’s ferocity. There was a constant danger off earthquakes, floods, fires, and even volcanic eruption from nearby Fuji. Yet, for Clark, Hokusai’s art portrays not man in opposition to nature, but man as part of nature.

“Hokusai presents to us our connection with the world,” he says.

“Let Me Live to Be a Hundred”

Hokusai’s life, as colorful as his work, also shows an uninhibited engagement with the world. He was something of a celebrity in his own lifetime and was an enthusiastic teacher, creating a series of drawing textbooks called manga (literally, “whimsical pictures”). He acquired money, but in typical Edoite fashion had little interest in holding on to it. And like many woodblock print artists of the time he produced shunga erotic prints. (These, although included in a previous British Museum exhibition, are not featured in this one).

Famously, he is said to have moved house over 90 times, often to evade creditors, and to have changed his name 30 times. At the age of 50, is even believed to have been struck by lightning—an ordeal that, characteristically, seems to have spurred him on to even greater inspiration and artistic endeavor.

As he aged, Hokusai’s dedication to his work—a task he believed was divine—only got stronger. He worked as feverously as ever.

“When I wake from sleep I pick up my brush and keep drawing,” Hokusai wrote to one of his pupils.

From his mid-seventies, Hokusai focused more and more on painting, and for the last three years of his life he set aside all other media. His final painted works are among his masterpieces.

At the age of 80, Hokusai wrote: “My eyesight and the strength of my brush are no different to when I was young. Let me live to be a hundred and I will be without equal.”

“Hokusai fundamentally believed that the older he got the greater he would become as an artist,” says Clark. “I think it was true.”

(Originally written in English. Photographs by Tony McNicol. Images of Hokusai works courtesy of the British Museum.)