“Cool Traditions” Stay in Tune with Modern Life

Best Face Forward: The Magic of Japanese Carpentry

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Beauty in a Board

Japanese carpenters can tell you a lot about a piece of lumber just by looking at it. They can see which is the root end and which the branch end, whether a log might twist as it ages, and where it is likely to split. This is not to mention knowing what kind of wood it is by the look, feel, and smell, how the wood was dried (and of course whether it is adequately dry to use), and which of many joinery methods will be the strongest and most beautiful in any given situation.

Most laypeople don’t even recognize this level of expertise, but we can easily see one very common way Japanese carpenters display their skill: the keshōmen (化粧面), or “decorative face” of a piece of wood.

A typical board of Japanese cedar (sugi).

A typical board of Japanese cedar (sugi).

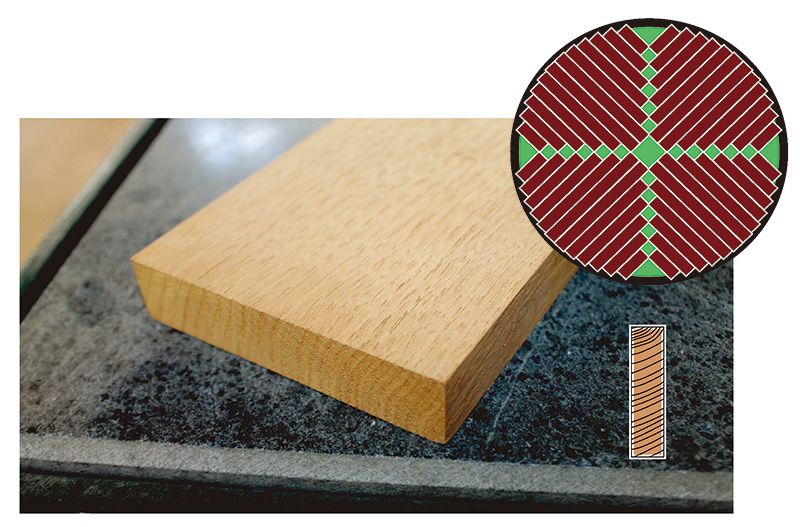

The distinctive arch pattern you usually see on the face of a board is the result of “plain sawing.” Plain sawing is the most efficient way to cut a log, leaving the center core to be used for columns, but carpenters consider it to be the least elegant way to present the wood.

Plain-sawn boards are cut flat from one side of a log until a set depth. The log is then turned 90 degrees and the process is repeated, until only a square column remains at the center. A board cut in this way generally has the end grain—the pattern visible on the ends of the board—running lengthwise along the narrow end face.

Plain-sawn boards are cut flat from one side of a log until a set depth. The log is then turned 90 degrees and the process is repeated, until only a square column remains at the center. A board cut in this way generally has the end grain—the pattern visible on the ends of the board—running lengthwise along the narrow end face.

The pattern is quite attractive and plain-sawn lumber wastes very little wood, but the “arches” that are visible on the lumber’s face also mean that it is somewhat weaker than a piece where the grain is vertical. Sometimes those arches will separate from the cut plane and curl up in thin, splintery wafers. Additionally, an imperfectly sharp cutting blade may catch on the growth rings and gash the wood. Plain-sawn lumber tends to shrink more as it dries, and may also “cup,” its face becoming concave.

Because of this, Japanese carpenters are particular about which side of a piece of lumber is the important face—the keshōmen to be displayed in the finished work—and which is unimportant. When they use a plain-sawn board, the face displaying the grain’s arches will necessarily be dominant—but the unsightly butt ends should be covered. A good carpenter can tell whether the board is likely to cup, and will make sure weaker boards are not used where they will be seen. When a plainsawn board is square or close to square in its cross-section, the carpenter will try to make sure the “arches” face is not dominant; the face with straight lines should when possible be the keshōmen decorative face, the side the user will see and touch the most.

Better Cuts for Gorgeous Grain

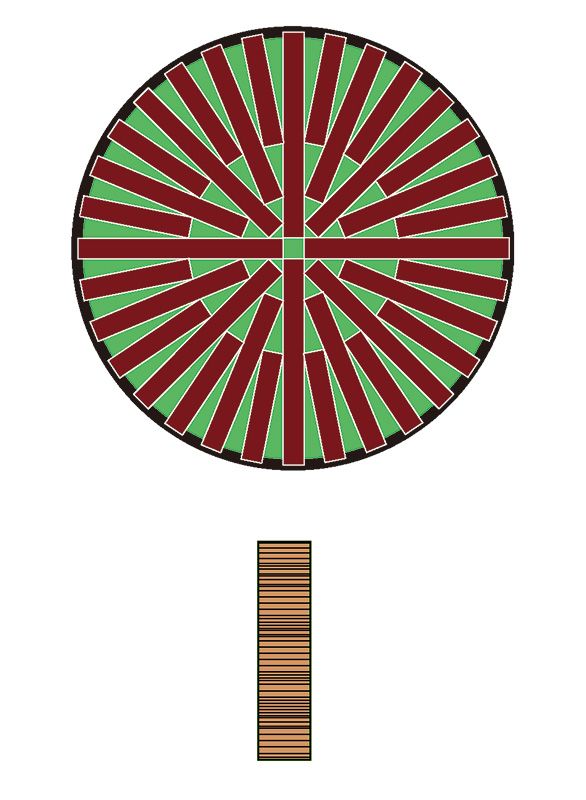

Quartersawn wood minimizes the problems of cupping, shrinkage, and splitting, but this method of cutting wastes more of the wood and is more work to produce, making it more expensive. However, every surface of the board can easily be used as a keshōmen.

For quartersawn wood, the log is cut into four quarters, which are then sawn into planks so that most of the grain is vertical to the cut face.

For quartersawn wood, the log is cut into four quarters, which are then sawn into planks so that most of the grain is vertical to the cut face.

Riftsawing is both time consuming and wasteful, so it is mainly used for expensive objects like musical instruments.

Riftsawing is both time consuming and wasteful, so it is mainly used for expensive objects like musical instruments.

Riftsawn wood is the most expensive. A log cut in this way results in every plank having its grain perfectly vertical to the plank face. Because of the considerable wood waste, however, riftsawing is very uncommon.

Japanese carpenters particularly use quartersawn wood in decorative areas like the tokonoma (a decorative alcove where art or arranged flowers may be displayed) or the genkan, the entrance hall where guests are greeted and shoes removed. These planks are often used where a butt end of the plank will be on display as well as the face. Quartersawn wood is stronger, flatter, and easier to plane or sand than plainsawn wood, so it is typically used in high-quality furniture.

Detail of a door made from quartersawn wood.

Detail of a door made from quartersawn wood.

In this age of robots, the beams and columns of a Japanese-style house are often delivered to a jobsite precut by computer, so the carpenters only have to fit them together and pound in the dowels. This method of construction has its merits, but can only be used for beams and columns that are perfectly straight. A traditional carpenter can fit together logs that are curved or twisted, creating the iconic beam structures seen in traditional minka folkhouses.

The next time you visit a traditional-style Japanese house, look at the floor trim in the engawa (veranda), the woodwork around the tokonoma, and the finish wood in the genkan. The best carpenters manage every detail, making sure each piece of wood has its best face forward.

A carpenter, fitting together beams for a minka home reconstruction, works with the natural curves and twists of the beams.

A carpenter, fitting together beams for a minka home reconstruction, works with the natural curves and twists of the beams.