Discovering “Nōgaku”: The Blossoming of Tradition

Helping Beginners Say Yes to Nō Theater

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Just a few blocks north of the Kyoto Imperial Palace, along one of the city’s major thoroughfares, stands Kawamura Nō Theater. From the outside, it looks no more than an elegant, private residence. I wonder to myself, “Could this building actually contain a theater seating 350 people?” I make my way to the entrance and, taking off my shoes, step inside—still skeptical.

The front gate of the Kawamura Nō Theater.

The front gate of the Kawamura Nō Theater.

What a surprise, therefore, to find a full-fledged nō stage just beyond the small lobby. Built using hinoki (Japanse cypress), the stage features a kagami-ita pine drawing by Matsuno Sōfū, famed for his paintings of nō plays; a traditional thatched roof; a hashigakari bridgeway with a balustrade; and a five-colored agemaku curtain separating the bridgeway and kagami no ma (mirror room), where the main actor puts on his mask. The seating area—with a high ceiling to accommodate the roof above the main stage area—was filled with high school students visiting Kyoto on a school excursion.

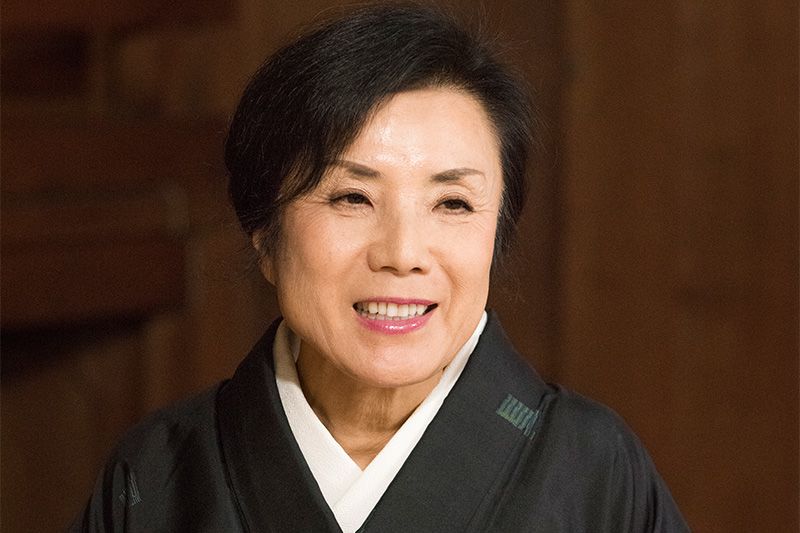

Kawamura Junko leads a workshop for high school students.

Kawamura Junko leads a workshop for high school students.

“Nō was popular theater in the old days,” explains Kawamura Junko from the stage in a clear, confident voice. “In the 1300s, it was what TV dramas or Broadway musicals would be today.”

Kawamura has been leading workshops like this one since 1996, when she and her late husband, Nobushige, developed an experiential program for nō novices. Many people in Japan tend to shy away from nō, thinking that it is impenetrable and hard to understand. The Kawamuras wanted to communicate its charms and make it more approachable.

Their effort has paid off, as the program’s popularity has grown through word of mouth. Some 400,000 people have participated in it over the years, mainly groups of students visiting Kyoto or employees undergoing corporate training. She led over 300 workshops in 2017 alone.

Getting an Audience’s Attention

Nō is a traditional stage art recognized as an important intangible cultural property by the Japanese government and—along with kyōgen (comedy performed alongside nō)—is inscribed in UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage. It originated in the mid-fourteenth century, making it two centuries older than Shakespeare.

Describing nō as a musical makes perfect sense, but the lines spoken by the actors are nonetheless difficult to follow, which is why modern audiences have shied away from performances. The language of nō, though, is not as esoteric as most people imagine.

“Most of you may think that nori ga ii (fast-paced, upbeat) is a phrase coined by modern comedians,” Kawamura tells her audience, “but it’s been around for hundreds of years. In fact, it comes from the nō theater to describe up-tempo musical sections of a play.”

Students listen attentively to Kawamura’s description of nō costumes, which, like this karaori woven using gold and silver thread, can weigh as much as 10 kilograms.

Students listen attentively to Kawamura’s description of nō costumes, which, like this karaori woven using gold and silver thread, can weigh as much as 10 kilograms.

The students look up, as if drawn by mention of a familiar point of reference. Kawamura knows how to get her audience’s attention.

“There’re about 250 plays in the nō repertory, and the greatest number are about ghosts,” she goes on. “You can look all around the world, but you’re never going to find another theater form with so many nonhuman characters. Those ghosts all enter the stage along the hashigakari, past the three potted pines. The world beyond the curtain represents other dimensions, and that’s where the ghosts dwell.”

The area beyond the five-colored curtain represents the abode of other-dimensional beings.

The area beyond the five-colored curtain represents the abode of other-dimensional beings.

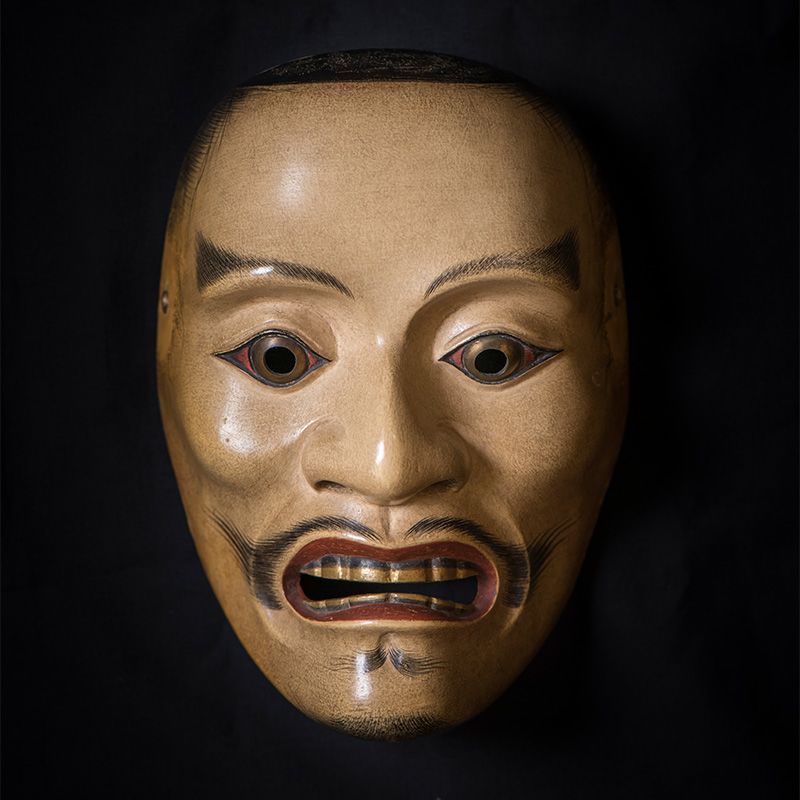

An ayakashi nō mask, used for the ghosts of fallen warriors. The outward expression of rage and resentment veils an inner dignity and calm.

An ayakashi nō mask, used for the ghosts of fallen warriors. The outward expression of rage and resentment veils an inner dignity and calm.

As Kawamura describes it, the ghosts enter the stage to recount their tale—their joys, pain, bitterness—to human characters (and, of course, to the audience) before exiting, usually feeling much lighter for having shared their story.

An engaging speaker, Kawamura stirs the imagination of her listeners. You can almost sense a shadow moving onstage as she describes its desire to speak.

Experiencing Nō Firsthand

Showing students masks, costumes, and musical instruments, she describes the most important props used in a nō play. No one is chattering, and no one has fallen asleep. Everyone is listening attentively, eager to hear what she has to say next.

The stage is considered sacred, and one must wear white tabi—no socks or bare feet are allowed. The hakobi, with heels flush with the floor, is the basic style of walking.

The stage is considered sacred, and one must wear white tabi—no socks or bare feet are allowed. The hakobi, with heels flush with the floor, is the basic style of walking.

The mask used in the play Okina, for which actors are required to remain ritualistically pure before the performance.

The mask used in the play Okina, for which actors are required to remain ritualistically pure before the performance.

“Do any of you recognize this face?” Kawamura says, holding up an okina mask. “It’s the River Spirit from the movie Spirited Away. The mask was also worn by the culprit in the Detective Conan anime series: Crossroad in the Ancient Capital.”

“How old do you think this character is?” she says, now holding up a ko-omote mask of a young woman. Most students believe it is for characters in their twenties or thirties. They are surprised to learn it is for a teenage girl—the same age as the students themselves.

“People assume that a mask can’t convey any emotions, but that’s not true at all. Tilted slightly downward, it has a sad expression; tilted slightly upward, there’s a look of elation. The shape of the mask didn’t change, so what changed was the emotion you ascribed to the mask’s expression. This is what nō is really about. The actor is responsible for only half of the theatrical experience; the other half is what the audience brings to the performance. When you watch a nō play, you’re participating in the creative process.”

The hannya mask can transform even an innocent schoolgirl into a vengeful monster.

The hannya mask can transform even an innocent schoolgirl into a vengeful monster.

The horned hannya mask is usually thought of as depicting a demon, but it is actually the face of a woman. When Kawamura covers up its oversized mouth, the face that appears is that of a woman in tears.

“It’s the face of a woman forced to endure great sadness and pain. One day, it just gets too much, and this is what she looks like when she explodes,” Kawamura says, adding, “So you boys better be careful never to cause a girl such grief. You’ll be very sorry if you did!”

Secret to Survival

The workshop concludes with a dynamic performance of an excerpt from the play Funa Benkei by her son, professional Kanze school actor Kawamura Kōtarō. The scene depicts the ghost of Taira no Tomomori seeking to avenge the defeat of the Heike clan at the hands of Genji warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune in the late twelfth-century Genpei War. Tomomori appears with a long naginata sword as Yoshitsune and his followers are fleeing their pursuers by boat in Osaka Bay.

“There are two main reasons that nō has survived for six and a half centuries,” Kawamura says. “One is that it continued to adapt and evolve over the years. The other is that its essence was transmitted from one generation of nō actors to the next not just through words or diagrams but as lived experience, particularly in the use of the body and voice.

Both those leading the workshop and students in the audience bow at the end of the workshop to express gratitude for one another.

Both those leading the workshop and students in the audience bow at the end of the workshop to express gratitude for one another.

“No matter what big changes the future may bring, remember to keep your feet planted on the ground, and you won’t get blown away,” Kawamura notes in concluding the workshop. “Be sure to think and act for yourself and to keep moving ahead.” With those remarks, she bows deeply, and the students reciprocate with a chorus of thank yous.

“Your senses don’t lie to you. When you experience nō firsthand, you can’t help but sit up straight. There’s a sensation of having come into contact with something profound. I think that’s why the students all express gratitude after the workshop.”

She receives many thank-you messages from the students. “I’ve promised grandma I’ll go see a nō performance with her this summer,” one wrote. And another commented, “Seeing how carefully nō masks and instruments were handled has convinced me to take better care of my soccer ball.”

Increasingly, Kawamura is asked to lead workshops for foreign visitors invited by the Foreign Ministry. She does so in English without an interpreter, choosing her words carefully to facilitate understanding for those unfamiliar with Japanese culture.

“I tell them repeatedly that nō is very simple. It’s that simplicity that fires the imagination. Nō can’t be fully understood intellectually. You have to feel it, and when you do, it can be a very powerful experience.”

The words may be hard to follow, for Japanese and non-Japanese audiences alike. But what is more important is to go beyond the text and give oneself to what is taking place onstage, appreciating the beauty of formalized movements, the chants and rhythms of the musicians, and the transcendental worldview of the plays. Not a few of her workshop’s participants have become fans of nō, encouraged by her advice to “feel” a live performance, rather than trying to understand it.Kawamura Nōbutai Nōgaku Omoshiro Workshop

- Address: 320-14 Yanaginozushichō, Kamigyō-ku, Kyoto

- Tel.: 075-722-8716, Fax: 075-722-8717

- Website (in Japanese): http://www.omosiro-noh-taiken.kyoto.jp/