Tokyo International Literary Festival

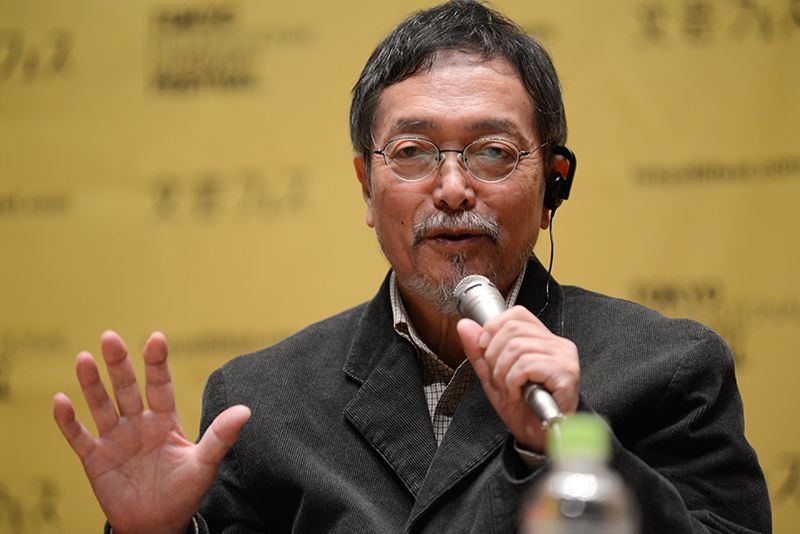

International Literary Salon: An Interview with Author Ikezawa Natsuki

Society Culture Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Travel, Migration, and the Rise of International Literature

INTERVIEWER Why have festivals like this become such a fixture on the literary scene in recent years—not just in Europe and America but in countries around Asia as well?

IKEZAWA NATSUKI An important reason is the changing cultural background. Literature is now something that is shared by readers in countries all over the world. The way people read has changed. We have moved from a series of national literatures to a situation in which what we might describe as “world literature” is now read across international borders. World literature for me means writing whose value is not lost in translation—works that, although they began life in a particular country and time, deal with universal subjects that resonate in different ways with readers around the world.

Why has this change taken place? The simple reason is that people around the world now share the same values. Our lives have grown closer to an extent that would have been unimaginable fifty years ago. People in Tokyo, New York, or Paris have more or less the same concerns. The same is true of Beijing or Vientiane. And it’s not just the big cities—lifestyles are converging in regional cities and rural areas as well, all over the world.

This phenomenon came about as the result of the remarkable movements of people that have taken place since World War II. Not just tourists and business travelers, but immigrants and refugees as well. This collision between different elements leads to the birth of new values. At the moment, literature is in the midst of an era of change, and new things are constantly being produced out of that struggle.

Globalization has made it possible for authors from different countries to come together. And instead of simply talking about the particular circumstances facing writers in each country, they can engage in a discussion based on a shared set of common values. These conversations allow authors to understand each other better, and that widens the terms of their discussions. They take the fruits of these discussions home with them—and this often has an effect on what they write next.

I lived for five years in France, where events like this are quite frequent. In a way it’s a little surprising that Japan didn’t have an event of its own until now. But now things are moving here too—at last! We’ve made it to the starting line now, and that’s a significant achievement in itself.

The Essential Role of Translators

INTERVIEWER As well as authors, a number of translators took part in the festival. How important is the role of translators to world literature?

IKEZAWA International literature of any kind would be unimaginable without translators. In a more authoritarian literary age, translation was often thought of as an unavoidable evil. People used to claim that the only way to truly appreciate Shakespeare was to read him in the original. But if you take that approach, then no one would be capable of enjoying all the world’s literature. Without translation, literature would be much narrower and more confined, hemmed in by the walls of language.

Translation is a highly creative endeavor. Two languages are “married” together, and something totally new is born. Some things might get lost in the process, but new elements get added too. The work can become more rounded away from the hands of the original author.

Bearing Witness to Injustice

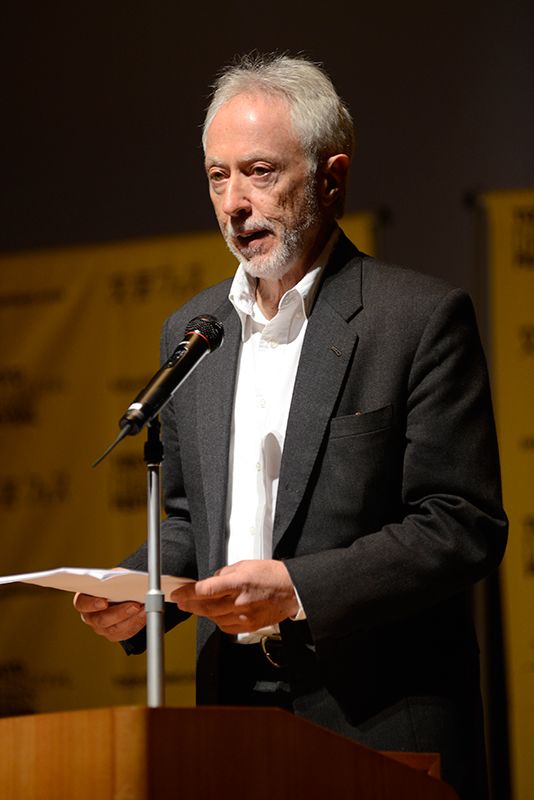

INTERVIEWER Some impressive names took part in the festival. Were there any highlights for you?

IKEZAWA I was thrilled that such an outstanding lineup of people agreed to come and take part. In particular, I was delighted that we were able to welcome Nobel Prize–winner J. M. Coetzee to Tokyo. I’m a huge admirer of his work. I believe he’s one of the most important writers of our times—absolutely indispensable to any discussion about the state of literature in the world today.

Coetzee has written a number of books that deal with the people who have been stripped or deprived of something important. Take Age of Iron, for example. The novel is set in apartheid-era South Africa. The protagonist is Mrs. Curren, an elderly white woman with terminal cancer, living alone without any relations. So that even though she’s not black, she still bears a heavy burden. Incensed by the injustices and violence of the society in which she lives, she gives careful thought to the question of how people should live and does her best to act accordingly. The book contains some marvelous depictions of human dignity. Many people around the world have had things taken from them, for a whole variety of reasons. Bearing witness to the injustices of their situation is another important subject for world literature.

March 11, 2011 and the Universality of Human Suffering

INTERVIEWER What about the earthquake and tsunami that hit northern Japan in March 2011? What kind of impact are those events likely to have in terms of international literature?

IKEZAWA The disaster took the lives of many thousands of our contemporaries. The nuclear accident that followed continues to have an impact today, and the danger is still far from over. There is no doubt that the situation will have a negative effect on future generations. How can we come to terms with the injustice of such a disaster? How do we mourn so many dead? In the two years since the disaster, people have tried to face up to these colossal questions and give expression to their feelings. Perhaps in that way we will be able to make some kind of sense of what happened and maybe find a way to deal with the tragedy.

When a major event like this takes place, journalists are the first on the scene. They turn the events into news stories. Next come the analysts and intellectuals, arguing about the background and causes. Then, last of all, come the writers. But they’re often the ones who understand the significance of what happened at the deepest level, by turning it into works of fiction.

When a major event like this takes place, journalists are the first on the scene. They turn the events into news stories. Next come the analysts and intellectuals, arguing about the background and causes. Then, last of all, come the writers. But they’re often the ones who understand the significance of what happened at the deepest level, by turning it into works of fiction.

Our suffering in Japan is the same suffering that other people are experiencing in different forms all around the world. All you have to do is look at the daily newspapers. Tragedies are also unfolding somewhere—whether it’s in Syria, Haiti, or Palestine. In that sense, I think there’s a good chance that the writing that comes out of the Japanese experience of March 2011 will resonate widely with international audiences.

This year most of the overseas authors came from English-speaking countries. In the future I’d like to think we could invite more authors from other countries in Asia and discuss these issues globally. I think it’s fair to say that we’re living in an age where close ties between writers from different parts of the world are more important than ever before.

(Translated from an interview in Japanese. Interview and text by Kondō Hisashi, director of the Nippon Communications Foundation. Photographs by Ōsawa Hisayoshi and Kodera Kei. With thanks to the Nippon Foundation.)

Japanese literature literature translation March 11 novels Tokyo International Literary Festival world literature Ikezawa Natsuki movement migration Coetzee Age of Iron