Frightfully Fun: Japan’s Ghosts, Ghouls, and Haunted Houses

Gomi Hirofumi and Japan’s Scariest Haunted Houses

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Summer: Season of Ghosts

The mention of summer conjures up all kinds of associations for people in Japan. Watermelon. Fireworks. Shaved ice. Mosquito coils. And haunted houses.

The history of the haunted house in Japan dates back to simple entertainments that were popular during the Edo Period (1603–1868). Today no amusement park in the country would be complete without its own haunted house. Most of these are year-round attractions, but it is during the summer “ghost season” that they really come into their own. One reason for the association with this time of year is the traditional belief that ancestors’ spirits return from the realm of the dead during the festival of Obon. Numerous special attractions around the country open for one summer season only, vying to attract visitors with new twists and tricks guaranteed to bring a shiver even during the hottest months of the year.

Gomi Hirofumi is a pioneer—the inventor of an entirely new type of haunted house and probably the first person in Japan whose business card describes him as a “haunted house producer.” For a quarter of a century now he has designed and produced ever more inventive and ambitious haunted house extravaganzas. His success has been instrumental in developing a new role for haunted houses, transforming them from an old-fashioned fairground ride for children to a sophisticated form of entertainment capable of thrilling and terrifying adults as well.

We interviewed Gomi in late May as he got ready for the busiest time of year in the run-up to the summer season. “I’m working on nine separate projects this summer,” he says, totting them up on his fingers. Most are limited-time specials that will run for one season only. One of these projects, Zakuro-onna no ie (The House of the Pomegranate Woman) has already opened inside the home stadium of the Hiroshima Carp baseball team. The event will run till the end of the baseball season in September. Gomi is also working on a permanent attraction due to open soon in Tateyama in Chiba Prefecture.

One of Gomi’s productions is Makai no koibumi (Love Letter from the Demon Realm), a year-round haunted house inside Tokyo Dome City Attractions. From mid-July through late September the haunted house is replaced by a special summertime-only attraction.

One of Gomi’s productions is Makai no koibumi (Love Letter from the Demon Realm), a year-round haunted house inside Tokyo Dome City Attractions. From mid-July through late September the haunted house is replaced by a special summertime-only attraction.

The Birth of a Pioneer

One thing makes Gomi’s haunted houses stand out more than anything else: audience participation. Visitors are given a “mission” and take part in a narrative that unfolds as they make their way through the house. And much of the excitement, fear, and tension comes from a cast of live actors who play the ghosts and ghouls that pop up to frustrate visitors in their task.

Gomi’s distinctive take on the haunted house tradition began at the Kōrakuen Amusement Park, the forerunner to today’s Tokyo Dome City Attractions. In 1992 he was a member of the planning and management team for a special summer attraction called Luna Park. With help from Maro Akaji, leader of the world-famous Dairakudakan butō dance and theatrical troupe, he came up with a haunted house project in which dancers painted entirely in white, their shapes grotesquely deformed by costumes and makeup, would suddenly appear and crawl toward visitors as they made their way through the house.

At the time, most amusement park haunted houses were tattered and faded, their popularity waning. The majority were simple rides in which visitors sat in a car and followed a fixed loop through unconvincing displays of stationary dummies and clunky mechanical tricks. Haunted houses that used real actors were all but unknown. Gomi’s recreation of the haunted house was soon one of the park’s biggest attractions, drawing huge crowds to its nighttime openings. Waiting times were sometimes as long as three hours.

A Sequel, Twenty Years Later

Tokyo Dome has since become something of a home base for Gomi, and he has produced a special haunted house there every year since 1992. It was in 1996, with Akanbō jigoku (Baby in Hell), that he first had the idea of giving visitors a mission and having them take the role of characters in a narrative that unfolded over the course of their visit. At the entrance to the haunted house, visitors were handed a baby doll. Their mission was to protect the “baby” from the ghouls that lurked in the darkness and deliver it safely to its mother at the exit.

“We’ve been running events here for 25 years now. People’s expectation levels get higher every time, which makes the challenge more difficult every year. But this summer, I knew from the time I made my pitch last year what I wanted to do. I’ve been looking forward to this for five years, waiting for the girl from Baby in Hell to grow up and come of age. And now the time has come. So this summer we’re doing a sequel. The idea is that the original baby has grown up and now has a child of her own.”

The mission—to escort a baby safely through the spirit world to a waiting mother at the exit—is the same. “But there are quite a few new touches,” Gomi says. “I’ve developed a lot in the 20 years since the original show,” he explains, a disarming smile breaking out over his features.

Turning Fear Into Fun

The revamped Baby in Hell opens on July 15. What steps do Gomi and his team follow over the course of planning and designing a haunted house and seeing it through to opening day? “Once the main idea, story, and mission are in place, I start to work on a production plan. What kind of experiences do we want visitors to have? How are we going to scare them, and what kind of route will they follow? Gradually my ideas take shape and I come up with a schematic plan for the kinds of things we want visitors to experience. Once the plan is in place, I’ll start discussions with my team of specialists—artists, doll-makers, stage mechanics people, and specialists in control technology, sound, lighting, and costumes. I give them an idea of the kind of thing I have in mind, and they get to work on their parts of the project.”

Gomi also gives detailed instructions for the interior of the haunted house. Once the building work is done, cast training gets underway. Gomi is closely involved in all the details, down to precise instructions to the actors on how he wants them to perform. “There’s a tendency for people to think that running a haunted house should be easy. Why do you need to worry about acting or planning in so much detail? People seem to think all you have to do is turn off the lights and make people walk through a maze in the dark. I suppose that’s why haunted houses are so popular at college fairs and other amateur events. But if you really want to turn fear into something enjoyable, and lift the haunted house into the realm of true entertainment, you need to think carefully about all the details of the acting and production. Making sure that the visitors enjoy the spectacle in the way the creator intended—that’s the meaning of true entertainment.”

Gomi says careful production is the key to creating a haunted house capable of entertaining adults.

Gomi says careful production is the key to creating a haunted house capable of entertaining adults.

Characteristics of Japanese Ghosts

Every year, after the basic construction work at Tokyo Dome City is finished and rehearsals are about to begin, Gomi visits the grave of a woman known as Oiwa at the Myōgyōji temple in Sugamo. Oiwa is one of Japan’s most famous “vengeful spirits,” a figure who has had a formative influence on Japanese ghost stories and horror since the story of her betrayal, disfigurement, and death was told in Yotsuya Kaidan, a popular kabuki play first performed in the early nineteenth century. Visiting the grave is a popular tradition for actors involved in stage or film versions of the Oiwa story; legend has it that failure to do so will result in injury or worse.

Gomi says the image of Oiwa continues to have an important influence on Japanese ghosts. “Almost all Japanese ghosts are women. Women who’ve been abused and murdered, often in particularly gruesome ways. They continue to feel resentment after death and this lingering attachment to the physical world makes it impossible for them to rest in peace. They haunt the living and seek revenge for the injustices they suffered during life. Many of the ghost stories that have been hits in recent years belong to this tradition: I’m thinking of figures like Sadako in Ringu [1998, Nakata Hideo] and Kayako in Ju-on [2003, Shimizu Takashi], for example. The details of the mistreatment they suffer and the special abilities they possess are different, but fundamentally they are the same. There is something about these characters and their stories that has appealed to generations of Japanese people.”

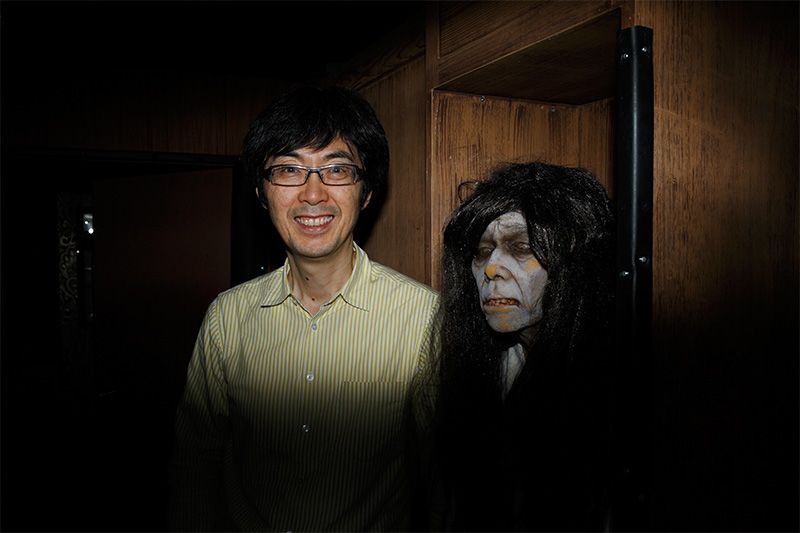

Gomi pays painstaking attention to details like the expression on his dolls’ faces. This chilling example leered at us from over Gomi’s shoulder throughout most of this interview!

Gomi pays painstaking attention to details like the expression on his dolls’ faces. This chilling example leered at us from over Gomi’s shoulder throughout most of this interview!

Japanese horror films like Ringu and Ju-on have become major international hits in recent years, inspiring Hollywood remakes—perhaps because this Japanese style of horror offers international audiences a new kind of spine-tingling thrill.

“I think a lot of people have been surprised by what they’ve seen of Japanese horror,” Gomi says. “Most of them probably hadn’t experienced quite this kind of horror before. Some aspects of ghost stories are universal. The idea of something with a physical power that is stronger than you, a power that can kill—this is something that terrifies all of us, wherever we come from. The powers of Japanese ghosts, though, are generally a bit different. Their power is not normally a physical power.”

Making Use of Local Traditions

The haunted house at Tokyo Dome City Attractions is just one of many that Gomi has produced around the country. Gomi says regional diversity is an important part of what makes his job interesting. “The idea is to create a haunted house that is unique to a particular area, something that is born out of the land and has a connection to local traditions.”

Gomi spends time researching a region’s topography as well as its history, people, and folkways as he thinks of a storyline. The haunted houses themselves make use of many different kinds of venues—from major event spaces like the stadium in Hiroshima to empty houses and abandoned buildings. Last summer, he put on a haunted house called Kuchi-nui ningyō (Stitched-Mouth Doll) in a disused commercial building in a shopping arcade in Takaoka, Toyama Prefecture. “Takaoka is famous for its metal-casting traditions, so I came up with a story that involved bronze.” The blue-green patina that gradually tarnishes bronze is an important motif in the story.

“There are still many places we haven’t worked in yet. In Tōhoku, for example, the only place we’ve done a house so far is Akita. Aomori, Miyagi, Iwate, and Yamagata are still uncharted territory. I’m really hoping to be able to do something in those prefectures. So if anyone from there is reading this, please get in touch! If I had my wish, I’d like to put on a project in all 47 prefectures. I’m sure there are stories and missions waiting to be discovered in every region of the country.”

Inside the haunted house Love Letter from the Demon Realm. Despite the nature of his work, Gomi says he never has nightmares.

Inside the haunted house Love Letter from the Demon Realm. Despite the nature of his work, Gomi says he never has nightmares.

Bringing a New Kind of Haunted House to Audiences Overseas

Gomi grew up in an old Japanese-style house in Nagano Prefecture, and as a child kept himself entertained by building his own “haunted houses” at home, shutting up the traditional tatami-and-shōji rooms in the dark. But he says he never dreamed that haunted houses would become his life’s work. “There’s no career path you could follow to end up designing haunted houses for a living! Things just went from one thing to another. Before I realized it, this was my job.”

Twenty-five years into his career as a haunted house producer, Gomi remains as ambitious as ever. His plans for the future include turning his attention to projects in other countries. “A lot of foreign visitors come and enjoy the houses we’ve done in Japan. I’d love the opportunity to travel to other countries and introduce international audiences to the haunted house as a form of entertainment for grown-ups.” Gomi says discussions are already underway on several international possibilities.

The main problem is time. “There’s only so much I can do at once!” Summer is the busiest time, but Gomi says he’s busy with projects throughout the year. He says the moments he enjoys most are hearing visitors’ screams as they pass through a haunted house, then watching them emerge grinning into the sunlight talking excitedly among themselves: “That was scary!” “Yeah, but fun!” These are the moments that make all the work worthwhile. “For me, it’s a dream job,” says Gomi with a grin.

(Originally written in Japanese by Itakura Kimie of Nippon.com and published on July 14, 2016. Photos by Ōkubo Keizō.)